Going to do a little old-fashioned blogging today and go through a big, compelling survey on American Parenting put together by the Pew Research Center. Some basics: the survey reached 3757 parents with children under the age of 18 between September 20th and October 2nd, and is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population when it comes to gender, race, ethnicity, politics, and education level. You can read a whole lot more (and find links to methodology) here.

Pew is great, and one of the things that makes it great is its ongoing attention to distinguishing how survey respondents of different races, classes, genders, political persuasions, etc., respond to questions. This seems like a straightforward thing to highlight, but so many junk surveys (which are often used to prop up pretty specious claims!) refuse to do it, either because it’s actually really hard to create representative survey pools or because it would complicate whatever headline they’re hoping to generate with the survey itself.

I don’t think Pew is infallible (please give me even more publicly available cross-tabs for basically every question) but I do kinda love the resistance to make survey results into clickbait of any kind. For example. the headline and sub-heading for this survey is “Parenting in America Today: Mental health concerns top the list of worries for parents; most say being a parent is harder than they expected.”

Lol, this is not news. But nuanced findings are interesting! Let’s talk about them.

1.) There’s an Ongoing Naturalization of Parenting as Exhausting and Stressful, Particularly for Mothers

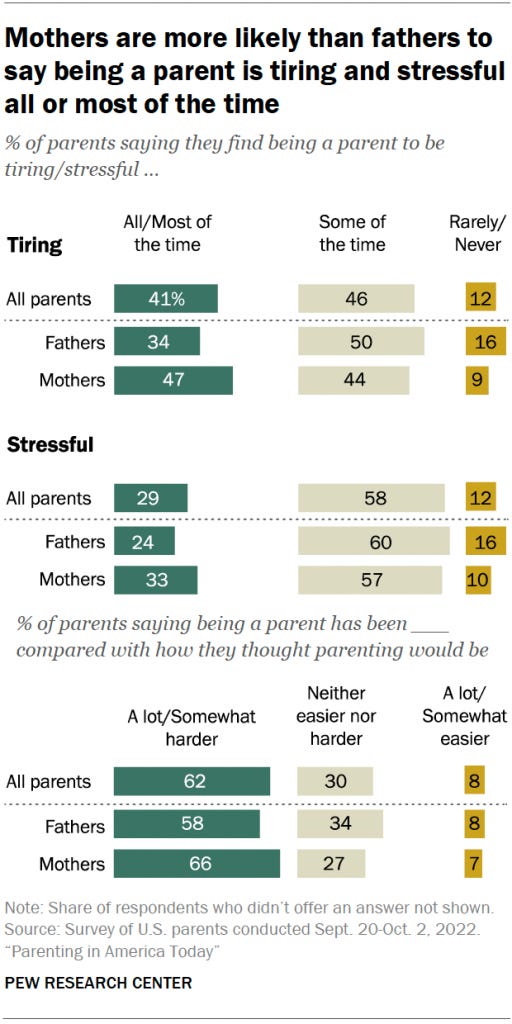

Sometimes it's useful to have these stats spelled out: a full 47 percent of mothers find parenting to be tiring pretty much constantly. (Also lol at 16% of fathers who never find parenting stressful or tiring). A third of moms find parenting stressful all or most of the time, compared to a fourth of dads.

Parenting feels consistently exhausting and stressful for a large percentage of parents, but that feeling of exhaustion and stress is felt more acutely by mothers….and even though everyone tells you that parenting is going to be harder than you imagine, two thirds of moms still think it’s even harder.

Some additional stats from elsewhere in the report: 57% of parents with children younger than five reported feeling tired all/most of the time, compared with 39% of those whose youngest child is between 5-12 year old, and 24% of parents of teens. This makes sense; none of this is surprising!

Same goes for these stats below, on who does more when it comes to parenting tasks + fathers’ enduring over-estimation of their own labor:

From hundreds of previous studies and articles and books, we know that moms do more parenting, and we know that fathers’ misperceive their parenting (see, for example, this classic of the genre from during the pandemic); all of it feels very “nothing to see here.” This lack of surprise is part of the point: we’re seeing on ongoing normalization of parenting as a life decision that’s “naturally” stressful and exhausting, particularly for mothers, and irrevocably unequal when it comes to the distribution of labor. And while caring for children can be exhausting and stressful, that does not have to be its base temperature. The same goes for unequal distribution of parenting labor. There’s nothing inevitable about it.

Indeed, there are very straightforward ways we could make parenting less exhausting and stressful, and do more to equally distribute those feelings of exhaustion and stress when/if they do occur. But there is little political will to put those policies and care infrastructure into place if we continue to understand this level of stress and exhaustion (and this enduring inequality of parenting labor) as “just the way it is.”

2.) But Parenting is Fun and Rewarding, Right?

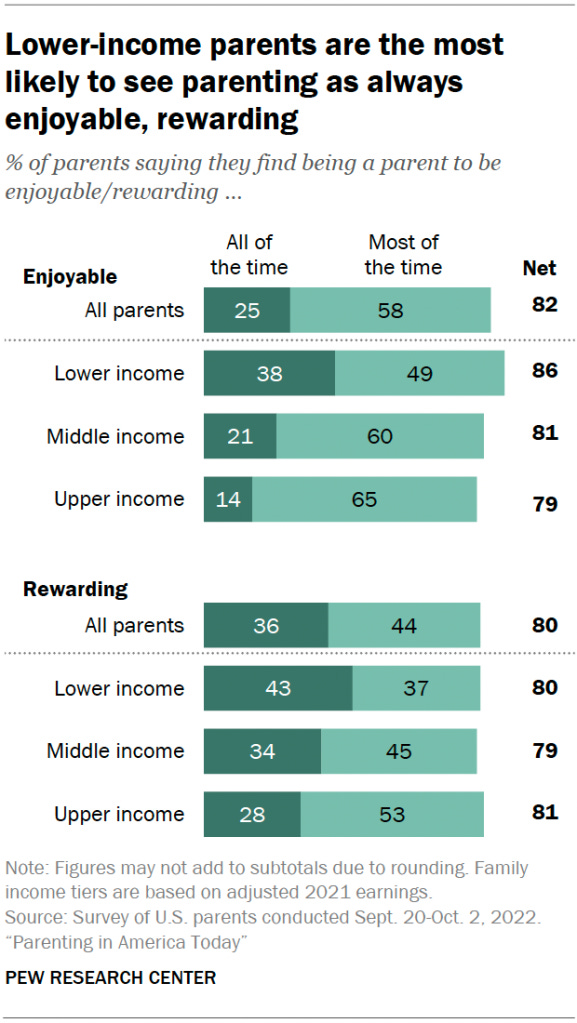

Well, most of the time. But it’s significantly more fun and rewarding for lower income parents than middle and high income parents.

Parenting with less money is hard in so many compounding ways — so how do we explain why it’s also more enjoyable and more rewarding? Sociologist Annette Lareau offers the most broadly accepted explanation: middle and upper-class parents approach parenting as a form of “concerted cultivation,” in which they work tirelessly to give their children the skills to reproduce their class position.

If you’re a middle or upper class parent, this style of child-raising (characterized by a loaded schedule of activities, “playdates,” enrichment, and, eventually, an overarching orientation towards elite college placement) has become so normalized as to, again, become unquestioned. But it’s exhausting, time-intensive and can transform the everyday labor of parenting into something more akin to management, complete with a sort of cost-benefit analysis for every activity, from a sleepover to reading at bedtime.

We know from elsewhere in the study that lower-income families prioritize financial stability for their children. We also know that lower-income families (and families of all races) understand “intensive parenting” strategies as the best way to raise a child. But just because you understand something as “the best” doesn’t mean that you have the means to access it — the classes and “enrichment” and tutoring and elite schools, but also more volunteering at a child’s school, and just generally allocating more hours towards “intensive” interactions.

Do lower-income parents feel anxiety about that? That’d be an interesting question to ask. Anger, apathy, dismay — but those are different emotions than anxiety, which so often stems from actually having the time and ability to do something, but then fearing you’re simply not doing enough.

3.) The Problem Isn’t Being *Too* Into Parenting

Or maybe it is. You might look at those Middle/Upper Class stats on exhaustion, stress, joy, and fulfillment and think: these parents are over-indexing parenting when it comes to their identity, that’s their problem. Nope!

The more money you make, the less likely you are to place ‘being a parent’ at the center of your identity. Part of this probably has to do with the fact that middle and upper-income people are more likely to understand their identity as their job, but even that doesn’t fully explain this stat. Instead, I’d argue that bourgeois parents are more likely to understand parenting as a performance — as an accumulation of activities and achievements — instead of an essence, a posture, or a source of internal meaning and worth.

As for why parenting-as-performance generally feels more stressful and shitty, well, it’s pretty hollow: you can check all the boxes and still feel like something’s missing, so you just keeping adding more boxes, and comparing your parenting to others’, then adding more “boxes” to beat them. It’s a similar phenomenon, I think, to buying a house, and realizing oh wow it’s not enough to buy a house — even though you thought it was a huge accomplishment and took so much to get there. You have to keep constantly remodeling that house. Chronic dissatisfaction with your surroundings is misery-making! Kids aren’t houses, but when you conceive of parenting as a game that’s possible to “win,” you’re more likely to find the entire experience unsatisfying.

3.) White and Asian Parents Experience Parenting Differently than Black and Hispanic Parents

This is a place where I would just love to see answers further broken down by class and immigration generation, but differences in parenting experience are still pretty staggering:

I’d also like to see a follow-up question that asks: what is parenting supposed to feel like? The answers here make me think there’s also racial differences in the understanding of whether an “enjoyable” or “rewarding” experience of parenting is even aspirational. For some, to not find parenting enjoyable isn’t a failure, it’s just not a priority.

4.) White Parents Care Significantly Less About a College Degree

What you see here is a pretty clear illustration of white privilege in action. More specifically: Black, Hispanic, and Asian parents understand the necessity of a college degree for their children’s future financial stability and success. White parents, even bourgeois white parents, understand it as far more optional.

(See the full survey for more details on class breakdown — including the surprising fact that only 35% of middle-income parents of all races thought it was very/extremely important for their children to earn a college degree)

5.) You Can’t Parent Your Kid Out of Racism

These stats offer a pretty striking distillation of the affect of systemic racism. Yes, you could attribute some of these discrepancies in worry/fear to recent high-profile national news events (I’m thinking specifically about the mass shooting in Uvalde and the increase in violent attacks against Asian-Americans). But these sort of marked differences in feeling are also derived from experience and observation. (See, for example, this study on the impact of gun violence on children and adolescents with statistics broken down by race, and this study on significant racial discrepancies in childhood exposure to neighborhood violence).

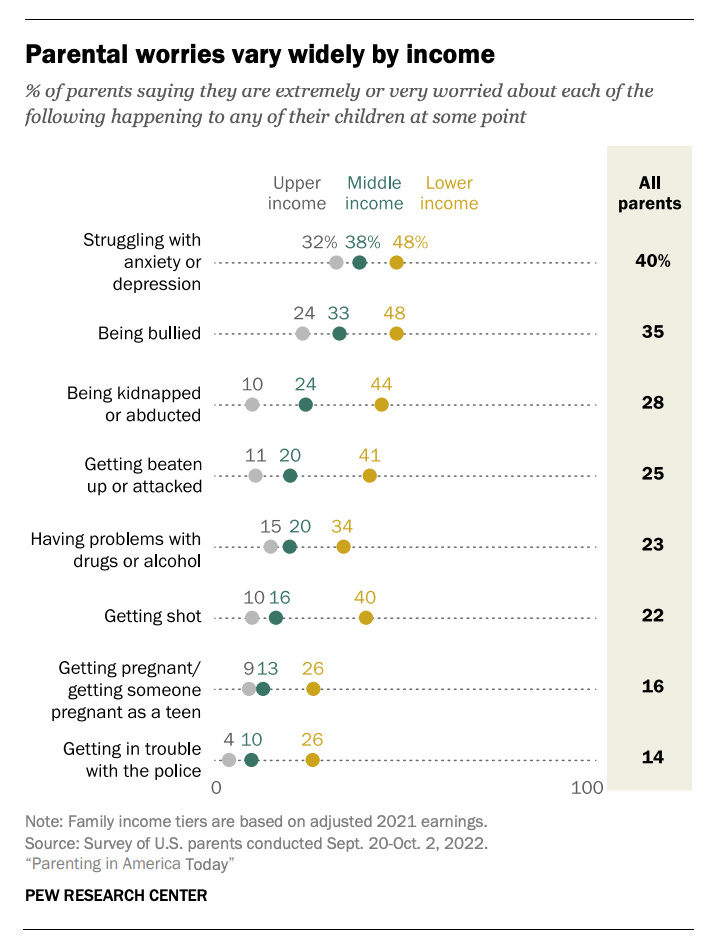

The full Pew study also notes that Hispanic parents who were not born in the United States have significantly elevated fears in nearly all categories, which points to what I see as a larger animating cause of fear: a feeling of helplessness to counter or control any of these challenges. Class status doesn’t protect against racism, or being bullied, or the anxiety or depression that might result from either.

You can teach your kids to avoid situations that would result in police confrontation, and try and keep close tabs on their friends and activities, but you can’t control the way police or the judicial system understand their threat level simply because of their race. As Dasia Moore put it in a Quartz piece on how “intensive” parenting norms differ by race, “while helicopter moms are busy multiplying their children’s privilege and advantages, many black moms are fighting to protect their children from the structural disadvantages that keep opportunity just out of reach.”

You cannot parent your kid out of racism, and that reality inflates the fear of a child getting kidnapped, or assaulted, or shot beyond the “rational” statistical probability. (By contrast, parents of white kids are probably underestimating their kids’ interactions with any of the above challenges, in part — whether they realize it or not — because they understand whiteness as a form of protection against them).

6.) You Also Can’t Parent Your Kid Out of Poverty

This one overlaps with the inability to parent kids out of racism, of course, but just look at how those worries shoot up for lower income families. Only four percent of upper income families are worried about their kid getting in trouble with the police — a percentage I guarantee does not correlate with the percentage of parents whose kids may be engaging in illegal activity.

7.) So What?

Studies like this one are a good reminder that we often talk about “parenting” — even with the specifier of “parenting in the United States” — as if it were a monolith. Within this understanding, race and income level make certain things about parenting harder or easier, but the fundamental challenges and textures and rewards are the same: it’s hard; there are more fears and challenges than ever; Moms are heroes; and you know what, it’s all worth it.

The reality is far more complex and contradictory. The American style of parenting is characterized by anxiety, but the source of that anxiety differs significantly according to societal privilege: there are parents terrified their children will drop down in class level, where they will then experience significant hardship, violence, danger, and ongoing difficulties, and then there are parents who are terrified because their children are already experiencing or in proximity to all of those things.

We also know that parents with the most acute fears due to race and/or income level are, on the whole, less exhausted and stressed and more rewarded by parenthood. By contrast, parents with fewer fears — whether due to class status or the protections of whiteness — are more exhausted and less rewarded. A harsh reading would be that parents with the privilege of whiteness and/or class start making up faux problems so as to create hardship they can complain about; a paternalistic (and racist!) reading would be that poor people and people of color are just naturally more happy because their lives are less “busy.” Neither of these explanations actually sufficiently explain what we’re seeing in the data.

Instead, I’d argue that middle- and upper-class white parents do, on some level, understand that there are fewer violent threats to their children — and that every parent should be able to parent free from those worries. But because of the way Americans in particular have been socialized to understand resource allocation and systems of power, they also think that there is no way for other parents to gain that privilege without them losing some of it.

For these parents, going “backwards” feels not just unconscionable, but terrifying. Which, again, makes sense: as a recent Brookings report made clear, as the income gap continues to expand, the ramifications of falling out of the upper middle class have become more severe. Falling down the class ladder isn’t something you can recover from quickly, like a cold. It’s more like a chronic illness that goes on to define the rest of your life.

As a result, bourgeois parents’ focus shifts to the reproduction of the status quo — of their family’s privilege — even if that reproduction makes parents and kids miserable, even if that ends up eclipsing the more meaningful and joyful aspects of parenting, even if that means enduring unequal labor distribution within the relationship, even if that requires transforming parenting into a performative competition. If people from other classes or races manage to scrap their way onto that level, they, too, must adopt the strategy of class reproduction and exclusion in order to maintain their place on the hierarchy.

Privilege always feels more powerful when fewer people have access to it. The system creates its own narrative of necessity, and squashes dissent, innovation, or just generally imagining a different way. What if the quality of your childcare didn’t depend on income level? How might universal preschool dramatically alter kids’ learning and health outcomes? How would guaranteed access to housing and medical care change, well, everything, for pretty much everyone, including and especially kids? How would mandatory extended parental leave regardless of gender change the distribution of labor in the home? What if we didn’t think of any of these programs and policies as taking away anything from anyone, but adding to everyone?

The shitty thing about this entire scenario isn’t that bourgeois parents could be suffering less. Getting stressed out over summer camp registration really does suck, but it sucks to a very different degree than grappling with the daily fears faced by kids without those particular privileges. The heartbreaking thing is that everyone could be suffering less — including people who aren’t parents, but are in parents’ orbit every day.

Parents can tell people to vote and agitate for change; they can work hard at teaching their kids not to be racist; they can get furious at headlines about class inequality and the wages of poverty. But the one way to actually change this system is big, hard, and counter-intuitive. Those with societal power and privilege can’t just say they want other people to have it, too. They have to be willing to share it. And sharing necessarily means letting go of what you’ve obsessively guarded as your own. If we want parenting to be easier, less fearful, less exhausting, and more rewarding for all — then bourgeois parents have let go of their white-knuckle hold and, quite frankly, do less of it.

I can understand how hard and abstract this advice can feel — and how we’ve been socialized to understand “less” as somehow “letting kids fall behind.” But that’s the hierarchy justifying itself. It might be helpful, then, to think about “less parenting” as performing less parenting. Love your kids all day long. Play with them, talk with them, work through tantrums, put them down to naps, listen to their Pokemon soliloquies, teach them UNO, get them gender-affirming health care, tell them to go play pretend by themselves, let them make bubble bath crowns out of their hair, all that good and hard stuff, please do all of that.

Just don’t mistake refining their human capital — molding them into ideal bourgeois citizens — for parenting. Because that work is not an expression of love, not really. That’s fear. And if your greatest fear is your child becoming poor, or losing the privilege and power you’ve accumulated, then you should pause, stop telling yourself that “you’re only doing what’s best for my family,” and think more about why and how you’ve come to accept that everyday reality for others. ●

Further Reading:

Casey Stocksill on de facto segregation in preschool and a whole lot more here in Culture Study

Annette Lareau, Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life

Allison Pugh, The Tumbleweed Society: Working and Caring in an Age of Insecurity

Tamara R. Mose, The Playdate: Parents, Children, and the New Expectations of Play

Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class

Malcolm Harris, Kids These Days

Why rich parents are terrified their kids will fall into the “middle class”

Eliot Haspel, Early Childhood Districts: A New Model for a New Era

Eliot Haspel, How to Quit Intensive Parenting

Claire Cane Miller, The Relentlessness of Modern Parenting

Dasia Moore, “Being a protective black mom isn’t a parenting choice—it’s the only choice.”

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s the weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, which is what one reader once described to me as “it’s own little town.” There’s a dedicated place to talk about grappling with this current round of layoffs, but also your DIY projects (with experts who will tell you how to do things!!!), and all your various movement pursuits. There’s a place to ask for advice, and talk about how to navigate a sticky friendship, and find help in your job hunt, and get support as we all deal with our weird and wondrous bodies. Plus there is so much more — if there’s something you want to talk about, there’s a space for it, and if not, you create it, and people will come.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

This is so rich! I offer my musings via a re-interpretation of a couple conclusions Helen made.

I disclose that I’m a nerd, a sociologist and while this (parents) is not my area, race and culture is. But more importantly I’ve been a Black single low then middle income mom amidst White affluent parents my whole life, many of which are dear friends. Lots of traveled terrain there.

Helen said: “The reality is far more complex and contradictory. The American style of parenting is characterized by anxiety, but the source of that anxiety differs significantly according to societal privilege: there are parents terrified their children will drop down in class level, where they will then experience significant hardship, violence, danger, and ongoing difficulties, and then there are parents who are terrified because their children are already experiencing or in proximity to all of those things… For these parents, going “backwards” feels not just unconscionable, but terrifying. Which, again, makes sense: as a recent Brookings report made clear, as the income gap continues to expand, the ramifications of falling out of the upper middle class have become more severe… As a result, bourgeois parents’ focus shifts to the reproduction of the status quo — of their family’s privilege — even if that reproduction makes parents and kids miserable, even if that ends up eclipsing the more meaningful and joyful aspects of parenting, even if that means enduring unequal labor distribution within the relationship, even if that requires transforming parenting into a performative competition.”

I would say something different:

I do not think the two experiences—between White parents and Black parents and between White affluent parents and low income parents—are that kind of two sides of a similar coin; two relatively different positions vis a vis a similar anxiety. I don’t think one group fears the worsening and the others are “already experiencing” it.

I think it’s more than one group belongs inside the monster that is White supremacy and the rest are its prey. Radically different positions. My White upper middle class friend who is parenting to make sure her boy has it as good if not better than she and her husband had it, is not afraid her boy won’t make it. She’s afraid he won’t be at the top. I am afraid the monster will eat my boy. She is never afraid of that. Even if I parent my boy to make it, relatively, most paths upward into the monster will put my boy in danger. He’ll have to bargain with Whiteness, be immersed in it to access “the best” (schools, courses, colleges, jobs), etc. Our relationship with that monster is always antagonist so of course dealing with that monster does not consume my parenting nor define it. My parenting may be more enjoyable because the monster has nothing to do with how I think of my parenting. The monster is something I try and slay so that I may parent at all. If that makes sense? Whereas my White affluent mom friend can and does harmonize with that monster as parenting success (sure it’s sisyphean but that’s not the same as what I deal with).

So, I would say that not being atop the social hierarchy—not fear falling backwards—is what is untenable for my White mom friend. And I would say that is always the motivation, the core function of being White, not an adaptive response to anxiety. This distinction is important because we are not seeing these patterns bc White parents are witnessing “falling backwards” as a real possibility (Lareau’s study is old and there are probably older data than that). The stats about White life expectancy decline are way more recent than these patterns. Sitting atop a racial capitalist hierarchy and collecting “the psychological wages of Whiteness (the psycho-social-cultural kudos of Not Being The Black or Brown People)” was the very engine of creating a White middle class. Always. White people were and are given a shot at economic status that’s always tangled up with racial and cultural privilege over others. Understanding that helps understand the resistance to change. When you’re asking parents to stop white knuckling that privilege, you’re asking them to stop working on being top of the food chain thus, and in some fundamental way, you’re asking to stop being “White” bc in our system to be White means to be on top of the food chain (hence for example the need to “cheat” that some White people feel say by rigging voting or more recently, banning books!). And we’d need to have a conversation about that before any “bourgeois parent” avoids a majority Black and Brown and middle income school or neighborhood like the plague, right? This is harder to hear than “you should give up some extra curricular activities” and that is because ultimately it is a harder ask and harder task.

Anyway I love this group is thinking about this.

Great read, with research that helps contextualize this trend! I first became a parent in 2000 when the culture was shifting to a more anxious style of parenting, at least for some. Clearly, this growing group of “security moms” was found more in two parent families with six-figure incomes times two. At 25, as a college educated married mom, I fell into that group but had no frame reference in my own family. My own mom never went to college, had her first at 19 and later divorced.

I’ve given a lot of thought to what parenting was like in the aughts, and have recently written about it. Looking back, I can laugh at a lot of things. But not everything. So much anxiety was needless. And my oldest Gen Z kid tells me, it wasn't so great for them either.

In my experience, a lot had to do with having a new generation of highly educated moms that professionalized motherhood. And then the internet took this to a whole new level. Every decision could be researched and quantified and compared.

But eventually I’ve learned that so many of the complicated parts of being a parent have nothing to do with the kids. Our parenting style is more about our own personality, privilege and need to feel validated. Over the years, I’ve gotten better at recognizing and owning my deeper motives as a parent. And as I do, being a parent feels a lot less complicated.