A Changing Same

I devoured Michelle D. Commander’s Passages, which focuses on the question of Black mobility, past and present, on a rainy-turning-into-sun early Spring day, and it’s been rattling around in my head as I’ve navigated the world ever since.

I wanted to ask Commander, who currently serves as the Associate Director and Curator of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery, so many questions about the book and her work, which occupies the intersection of academic and “public-facing,” of historic analysis and personal essay. Her answers, like the rest of her work, have challenged and re-textured my perception of compulsory, controlled, and unfettered movement — and I think they’ll do the same for you. Spend some time with these. Let them rattle around in your head, too.

Can you tell me a bit about your path to academia and how you arrived at your area of study, just generally? Was there a specific moment when you thought: this is what I’m meant to think about, and keep thinking about?

There were two significant moments that occurred during my graduate school career: my decision to leave a PhD program in Humanities after two years in order to enroll in the amazing doctoral Program in American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California (USC); and my travels during the summer after my first year in that program.

My first year at USC was the most challenging academic experience of my life. I had a lot of learning to do. My friend Sionne and I decided to take a month-long trip to Accra, Ghana, the summer after that first tough year. It was my first visit to the continent of Africa and I was in awe of nearly everything I saw, including the number of Black American expats there. I felt such a connection to the people and the place that I started informally interviewing expats to get a sense of their reasons for leaving America and their experiences grappling with transitioning to a new life in a country full of so many beautiful and distinct cultures — as well as a disheartening history of transatlantic slavery and colonialism whose remnants were so evident there.

Subconsciously, I was grappling with my own responses — how could I feel at home in this place after a week? Were some of my ancestors stripped from here? After many years of research for my dissertation (on the topic of Black expatriates, Black American longings for and imaginings of Africa, and roots tourism, which I eventually expanded into Afro-Atlantic Flight: Speculative Returns and the Black Fantastic), I have been consumed with thoughts about the limits and promises of Black mobility. I reflect often on where and how I was raised, given the society that we are made to negotiate.

Your book is part of the Avidly Reads imprint for NYU Press, and focuses on “Passages” — and the way that mobility, in all its forms, has been historically constrained for Black Americans, and travel has been “an incredible cruelty and longed-for possibility.” Can you tell us a bit more about the scope of the book, and what you hope readers will carry away from it?

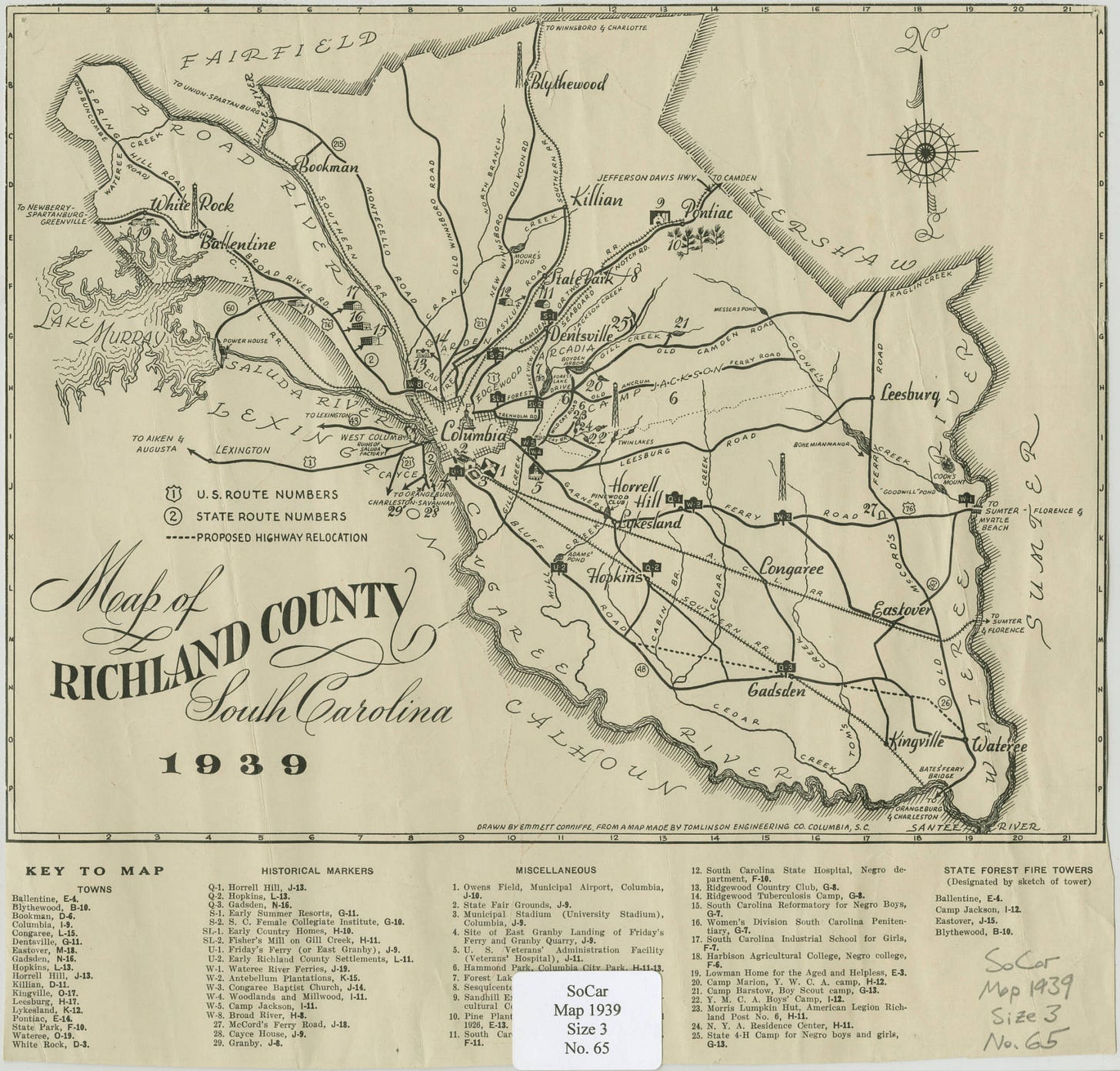

The book considers four modes of transportation — the slave ship, train, automobile, and bus — and situates their importance to ideas of modernity and progress to the United States as well as the promises, limitations, and cruelties their presence has meant for Black Americans. It focuses on my hometown — the Lower Richland area of South Carolina — to tell a story about working class Black Southern life in the shadows of former slave plantations. My hope is that readers will take away further knowledge of the ways that Black people’s movements have been monitored and restricted in coordinated ways, both by law and in everyday interactions, since slavery. This persistent desire to control Black mobility is a stunning, centuries-long phenomenon. A changing same.

Can you share the story of the “Steel Man” image and what it communicates about your Grandfather, his life as a “railroad man,” and the relationship between Black labor and the Southern train system? As you write: “Here’s something I know about the experience of my ancestors: exerting two centuries worth of generational labor on Lower Richland soil under the most brutal and corrupt circumstances must have involved herculean physical and mental strength.”

My grandfather Thomas Gilford passed away when I was just nine months old. My mom talks often about how much her father loved me — that he joked (or maybe he was serious. I like to think so, at least) about adopting me. When I look at his face in this picture, I feel loved and at peace. I bet my Aunt Hilda did too back in the 1990s when she commissioned the artist Larry Francis Lebby to create a signature, india ink wash-sketched portrait from a rare photo that we have of her father, my grandfather.

In Passages, I describe my recent discovery that Lebby created at least one more version, which has been part of the collection at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina, for more than twenty years. “Steel Man” is Lebby’s title for the piece and refers to the work that my grandfather did in a steel factory. I also interpret Lebby’s use of “Man” rather than “Worker” as Lebby’s belief that Thomas Gilford was a “man of steel,” not someone who was above human feeling or the stress of the world, but someone who persevered and was, in a way, heroic for doing the best he could despite all of the brutality and unfairness that he witnessed and experienced in his lifetime. Thomas Gilford, indeed, was more than his work title.

I am proud of my grandfather for laboring so hard to take care of his wife and children. When I think about what I know about his life from family lore and the archives, I feel a range of emotions: sadness and rage about the known struggles, and comfort and amusement in response to the humorous and inspiring stories. I’m not sure how any Black person in America in generations prior to mine survived the violence, dehumanization, racism, second-class citizenship, and hatred. I don’t know how we survive it now, honestly. It’s rough. It hurts. So often we’re gaslighted, our humanity ignored. We hold on to family, friends, and loved ones tightly and aim to create spaces of joy, in spite of all of the new and utterly disturbing ways that this nation tells us that we do not belong.

The book is physically small (I might even call it a pocket book?) and compact in length, coming in at just under 150 pages. It reads quickly — I read it over the course of a few hours — and packs a real punch. What did you appreciate about the bounds of this project? What were you able to do that you might not have been able to with a more “traditional” non-fiction book?

A pocket book, yes! I remember thinking at the outset that 30,000 words was not very long and that I could finish the manuscript in no time. Ha! Then, I had to sit down and write 30,000 words. It alternatively felt like too much and not enough room to tell this story. This was the challenge: I needed to elegantly fit in a decent history of Lower Richland, South Carolina and modes of transportation, personal reflections, and archival materials in order to tell a complete story.

Passages is the toughest piece of writing I’ve completed to date. The short book format let me off the hook in some ways. I was able to move more confidently and (I hope) more smoothly back and forth between time periods because the story did not get too bogged down in historical intricacies. At the same time, I had to tamp down my training as an interdisciplinary scholar. I found myself wanting to add more passages: literary references, sociological considerations, historical background, and so on. This format forced me to simply get to the heart of the story.

What does Lower Richland feel like today? Would your ancestors recognize it in feel, in freedom? What does it feel like for you?

Due to the pandemic, I have not been to Lower Richland in over a year. I miss the place and my family terribly. There was a time just after high school that I could not get far enough away from home. I wanted to show how grown I was. I wanted to live my own life. My parents had never been too strict on me and they had always supported me, but I still somehow thought that I needed to be independent. At 42, I lament how firmly I held on to that outlook, though my independent streak resulted in my feeling confident enough to go to graduate school in Florida just after undergrad and all the way to California, where I have few family ties, to pursue my doctorate.

When I am back in Lower Richland, I am there as a native daughter of the place and people and also as a scholar. My time there is precious. There is so much I have missed over the years and everything has aged just as I have aged. Lower Richland is different and I am different. I am fortunate in that I understand much more of my upbringing due to my maturity and my scholarly training. My love and gratitude for Lower Richland has been increased by both.

When I’ve traveled through Lower Richland in more recent years, I found myself giddy when things that I thought of fondly in my youth — beautiful and tended fields, my favorite homes along still familiar stretches of road, country stores, and thick forests have remained intact.

There are areas of the region that would likely be recognizable to my ancestors because the land has remained untouched. My ancestors would be proud that we — their descendants — are surviving, thriving. I think they might be saddened by the fact that most of us have left: that many of the places they helped establish no longer exist. They would probably not be surprised by the necessity of our movements away from the area given the lack of consistent opportunities for upward mobility over the years and the ways that racism and inequality have remained a curse on every subsequent generation to varying degrees.

I love what you write at the very beginning of the Acknowledgments: “I have been thinking about this book for several years now and Lower Richland, South Carolina, for my entire life.” I think a lot of people have been thinking about the places they’re from, in some way, for their entire lives, but don’t always have a framework for organizing those thoughts. Do you have any advice for readers on how to start the work of approaching and expanding their thoughts about place and space of home, and the passages that bring us to and away from it?

One useful question that informed how I researched and organized the book was “How did we get to Lower Richland?” I literally sketched out how my family and people of African descent arrived in Lower Richland, South Carolina. I could not say from where in Africa my ancestors were kidnapped and sold or when the atrocities commenced for them with full certainty, but I knew we came by slave ship and across the Middle Passage. My next considerations grew out of that first question: How did my ancestors help ensure our family’s survival into the contemporary moment? How did other passages such as laws and modes of transportation to render physical movement more efficient impact Black mobility and progress?

Depending on the familial history of the reader, the starting question could be some version of the following series of questions: Why did my family come here? How did my family arrive here? Why did my family stay here? What promises did this place offer? Who has left and why? And who has returned — and why?

You can buy Passages via Bookshop here, and follow Michelle on Twitter here.

If you read this newsletter and value it and the writers it introduces you to, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, which are thus far still one of the good places on the internet. Tomorrow’s Friday Thread is going to be a very good one.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

You can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.