A New Kind of Forensics

"Can you think of any other technology designed to hold men accountable for brutalizing women?"

This week’s episode of is one I’ve been wanting to do since we first launched the pod — interrogating all the ways “self-care” has shown up in workplace trainings and family dynamics and anti-burnout advice since 2020. Of course I asked to be the co-host, because no one is as clear-eyed and compassionate when it comes to why we need self-care — and why brands and workplace trainings are so bad at actually providing it. Listen here or click the magic button to listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Also: Big Exasperated Sigh, because when I rebooted the “Ask Me, A Divorced Person” sign-up Google Form from 2022, and dozens of you very kindly agreed to offer your expertise as a Divorced Person….the form defaulted to no longer requiring email addresses (this is part of the general Google Suite Revamp).

If you responded before, please accept my apologies for this annoyance — and if you could go back into the form (which is now definitely collecting email addresses) and just reference something from your previous response (I’ll find it, you don’t have to retype it!). Or, if you missed the previous call-out and want to be part of a panel of anonymous Divorced People answering questions, here's how you volunteer. Thank you all for your patience and your willingness to help make this community a real resource for others.

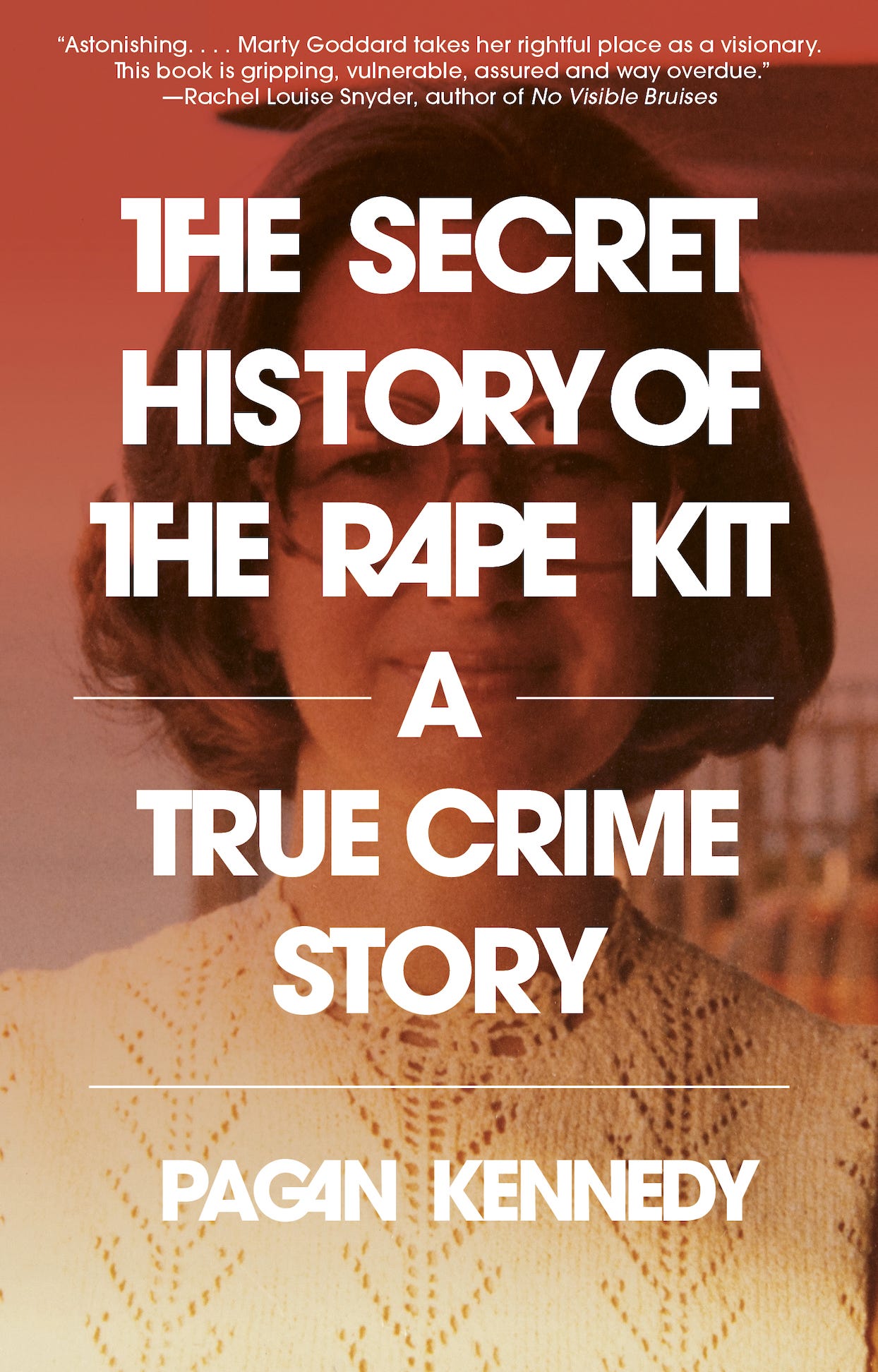

“Often it’s impossible to determine the exact moment when an idea becomes a thing.” That’s one of many things that journalist Pagan Kennedy says in our interview below that twisted a screw in my brain — particularly when it comes to the rape kit, an invention I hadn’t even thought of having a history, let alone a convoluted and obscured one. But of course the rape kit has a history, and of course the history of one of the only devices “designed to hold men accountable for brutalizing women” would be convoluted and obscured.

The Secret History of the Rape Kit recovers Marty Goddard’s central role in the invention of “a new kind of forensics” — one that made rape provable, and, by extension, made survivors believable. It’s one of those stories where you’re like, thank god we have this tool, but also: what sort of society makes survivors believable only through science? That’s one of many realizations I’m still turning over after this interview. I know you’ll have some as well.

**Content Warning: This interview includes reference to sexual assault (but not description). If you’re not in the place to read that today, please go ahead and skip; another Culture Study will be waiting for you on Sunday.**

I have a vivid memory of reading your piece on Marty Goddard and the invention of the rape kit in the New York Times when it first came out in 2020, in the depths of the pandemic when I felt both addicted to the internet and repulsed by it. The line that stuck out to me, both then and now: Can you think of any other technology designed to hold men accountable for brutalizing women?

As a way of starting the conversation, I’d love to hear about the rape kit as a piece of technology — a “new kind of forensics,” as you put it in the book — and what made it (and Marty’s work) radical.

In the early 1970s, Marty Goddard volunteered to answer calls on a hotline for teen runaways – and that’s how she discovered a hidden epidemic of child abuse and sexual assault.

At the time, police rarely bothered to collect evidence or pursue rape and child-abuse cases. The women and girls who reported rape were treated as hysterics, liars, or attention-seekers. A typical police training manual in Chicago instructed, “Many rape complaints are not legitimate…It is unfortunate that many women will claim they have been raped in order to get revenge against an unfaithful lover or boyfriend with a roving eye.”

Marty Goddard made it her mission to create an entirely new system that would produce powerful evidence of sexual assault – the kind that would stand up in the court room.

Her idea revolved around a rape kit that would guide medical workers as the gathered swabs, clothing, and other physical evidence. But the system went way beyond the kit: Marty Goddard trained nurses, doctors and police officers to work together to collect physical evidence — like swabs of semen — that could help identify the perpetrator. She raised money to build a statewide network of hospitals and forensic experts. And she pushed for police departments to treat survivors with respect.

Most significantly, she helped to bring about a new idea: That all survivors were entitled to a forensic exam and to have their evidence analyzed in the crime lab.

In the early 1970s, rape was seen as an “unproveable” crime. By the end of the 1970s, cities across the country were beginning to create their own rape-kit programs and to bank evidence of sexual assault.

There’s a version of this book that would’ve just been the history of the rape kit: why it matters, how it changed the ways we hold people accountable for assault, what led to the backlog of testing, etc. But coupling that story with Goddard’s — and the way she, herself, disappeared from both the history of the rape kit and from society — transforms the book.

As you put it, “It seemed logical, then, that the most effective inventor of a sexual-assault forensics system would be a woman. And it also seemed cruelly inevitable that a man would be the one to receive the credit.” (I’m also thinking about small details like how difficult it was for Marty to even get a credit card to buy clothes to get in the rooms to advocate and raise funds).

Can you talk a bit about how you conceptualized the telling of both histories, and how it changed as you continued to investigate Goddard’s past?

While working on the book, I discovered that the Chicago rape kit was not the world’s first. A number of cities, towns and hospitals began experiment with kits that would be used to collect evidence from the victim’s body.

Some of these early kits were shockingly terrible – for instance, one kit developed in California in 1973 instructed the police officer to refuse to collect evidence from a woman whom he judged to be a “sleazy free-lance prostitute.” The design of that kit (and others) reflected the ethic of that time. Back then, police officers were trained to believe that many women who “cried rape” were lying.

Over and over again as I researched police practices of the early 1970s, I was shocked by what I found. For instance, officers might pass around photographs taken of blooded and bruised rape victims, ogling these as if they were girlie magazines.

But for the most part, police just bother to investigate sexual crimes at all. There was a widespread belief that rape was different that other crimes, like murder or robbery. You couldn’t prove it happened. Every case would end up as a he-said, she-said. It was his word against hers, and she was probably a liar.

The Chicago rape kit succeeded because it was entirely different in spirit from its predecessors. Marty Goddard and her collaborators pushed for a new kind of professionalism. They began with the idea that you could prove that a rape had occurred, that this was a crime like any other. They created a kit that would be used by trained nurses who understood exactly how to create a chain of evidence – how, for instance, to collect slides that the crime lab would use to analyze blood or semen.

Goddard had been outraged when she witnessed police officers abusing rape victims and crime labs throwing out evidence. So she made it her mission to change the culture — to push for a system in which every survivor could report to a hospital, receive a forensic exam and have her evidence analyzed in a lab.

One of the things I love about a book-length project like this is that instead of just telling us what you found, you’re able to give us a play-by-play of how you found it — the narrative is, in part, the journalistic process. What was the trickiest part of reporting this story, and how did you figure it out (or maybe you’re still trying to figure it out, that’s interesting too!)

This was the most ambitious reporting project of my life-time. Because there was so little known about the history of the rape kit when I started, I had to track down dozens of people and hundreds of archival documents to figure out how the American forensics system had evolved. That made the investigation thrilling; often-times I was the first reporter to call up or visit a source. I found people who had been waiting to tell their piece of the story for decades. Often an interview or an old newspaper article would wallop me with some kind of unexpected clue that would completely change my understanding of the story.

For instance, when I tracked down and interviewed a woman named Margaret Pokorny who had helped Marty Goddard to raise the money needed to launch the Chicago rape-kit program. While we were talking, Margaret suddenly remembered that back in the 1970s, she had stitched a tiny needlepoint rug to give to her friend – and that’s how I learned about Marty’s fascination with miniatures. Marty would create doll-sized rooms furnished with elegant sofas and paintings, wiring them with electricity so that the itty-bitty lamps turned on and off. She seemed driven to create safe and perfect little worlds — and I would later learn from Marty’s friends and relatives just how this obsession drove her.

Though I wouldn’t usually take the reader along with me on the research project, I felt that I needed to do that in this book because the twists and turns were just so crazy. Also, I felt that it was important to be completely transparent about the process that I’d gone through in order to piece together the story, and also to make it clear to the reader where there are still gaps and mysteries.

There’s a fascinating section of the book where you talk about the history of the American patent system and how it facilitated the white men’s theft of intellectual property from women and people of color…..and how the patent registry was then used to reinforce the idea that only white men had good ideas!! I’d love if you could explain some of that history, and how it relates to Marty Goddard “ceding” of the rape kit invention to Louis Vitullo.

For a couple of years, I worked as the “Who Made That Guy” at the New York Times Magazine. Every week, I would tell the story of an ordinary object and the person who created and shepherded it into our reality. That job had me constantly hunting through the patent system for clues – how did this thing (i.e., the pencil eraser or the tennis-ball hopper) ever come to be? But it also taught me a lot about the way that the true story of an invention can be erased – and I began to think a lot about who gets to control the way things are designed and who benefits from a certain technology.

Often it’s impossible to determine the exact moment when an idea becomes a thing. This is absolutely true of the rape kit. There were lots of little local experiments in the early 1970s with creating a kit for sexual assault forensics. So Marty Goddard shouldn’t be called the inventor. Nor should Louis Vitullo. And yet, the kit was special because of its design “point of view” — my research shows that Marty Goddard was largely responsible for the way the kit was deployed. She recognized that all too often police officers or hospital workers would blow off women who seemed “loose” or “not upset enough” or “crazy.” She tried to take the biases out of the system, so that it would be possible to see the shape of this enormous public-health problem of sexual assault. Marty recognized that you had to collect evidence in an evidence-based way.

You start the book with a description of your own assault — and your reaction, many years later, to watching Christine Blasey Ford testify about her assault by Brett Kavanaugh. Why did it feel important to root this book, from the beginning, in the personal?

I wrestled with whether to weave my own story into the book. I was attacked just two times in childhood and I felt that what I went through was minor compared to the years of abuse endured by other survivors.

And yet I also realized that because my experience was so typical of that time, I could use my own story to help vividly recreate the era of the 1970s when Marty Goddard was working to build the first large-scale rape-kit system.

I grew up at a time when little girls were usually blamed for their own abuse. So I kept silent. And honestly, I don’t think I really understood that sexual assault was a crime until I was mid-way through college in the 1980s.

When I went back and researched that era for this book, I was shocked at what I found. For instance, a story in the New York Times, titled “Little Ladies of the Night,” complained about the problem of 13-year-old girls turning tricks in midtown Manhattan. No one seemed to wonder who had put those 13-year-old girls on the street and was forcing them to sell their bodies. All this child abuse was happening right out in the open, and yet almost no one saw it.

Recently, I also stumbled across some 1970s instructional videos meant to teach women and girls how not to get raped. You were supposed to fend off attackers with hat pins and karate chops. These archival films are hilarious – and also super-disturbing. Girls of my generation were raised to believe that we had to fight off a rapist because no one was there to help you – you were on your own. The world was not built for you and you could never feel safe. ●

You can find out more about Pagan Kennedy’s work here, and buy The Secret History of the Rape Kit here or here.

Many of the people who read this newsletter the most — who open every issue, often multiple times — are people who haven’t yet become paid subscribers. So if that interview made you think, if it shifted something in your brain, if you keep meaning to subscribe but keep forgetting to actually do it — maybe this is the push you need.

Or maybe you just want to hang out in yesterday’s 500+ comment thread re: What Games Are You Playing? Both motivations are valid!!!

From my years working at a rape crisis center I can confirm two things: 1) The people who administer rape kits are some of the greatest and most compassionate humans on the planet. and 2) Undergoing a rape kit is still a grueling, miserable experience. Imagine you've just been through an unthinkable trauma. Now you're spending hours being photographed, your hair is being pulled out (from your head and other places). You're being poked, prodded and scraped and you're being forced to tell your story over and over again. You give up your clothing - all knowing this is just the beginning of a long road that probably won't lead to justice. The men and women who choose to go through this are absolute warriors and those who don't have every reason not to. I look forward to reading the book - it is much needed.

I’m a former hospital advocate and a sexual violence researcher. I want to offer up an important correction on this essay:

Rape kits can’t “prove” rape. They offer evidence that there was physical contact between two people, but most rape kits aren’t particularly useful evidence in a courtroom, especially if the perpetrator’s identity was already known and he claims all contact was “consensual.” A lot of the time, victims go through the trauma of a rape kit just to learn the physical evidence wouldn’t actually matter much in their case. (That being said, the trauma-informed interview conducted by the SANE is much more useful evidence.)

In my research work, I’ve come across survivors who felt really betrayed by their rape kits because they had been misled to believe they could “prove” rape. In one case, the survivor’s rape kit documented bruising and strangulation, but it was still used by her perpetrator’s legal team as proof that all acts were consensual “kinks.” It broke the survivor’s heart to hear her SANE admit that consensual BDSM and injurious rape would produce the same rape kit. It made her wonder why she had put herself through it at all. I think that’s really important to acknowledge here.