Some of these interviews I track down myself — but a bunch of them, like this one, are the result of readers sending recommendations my way (thank you Siena). If there’s a new book coming out (or coming out in paperback) or new-ish research you think would be a fit for a Culture Study interview, send me an email at annehelenpetersen at gmail dot com (if you know the author, check with them to see if they’d be game to do an interview; if you don’t, let me know anyway (that includes you, everyone who subscribes to this newsletter in the book industry).

The first way I really made a name for myself, writing on the internet, was writing about Classic Hollywood stars. This was back in 2011, when any time I had leftover from writing my dissertation I devoted to reading The Hairpin, a weird and wonderful little website spun-up by a handful of writers in the wake of general media impulsion of the late 2000s. I emailed the editor and asked if I could write about what, at that point in my academic career, I knew by heart: not just the scandals that surrounded these stars, but the way those scandals were mediated, framed, consumed….the way they came to mean.

Those columns, which eventually grew to somewhere between 4000 and 6000 words a piece, attracted the attention of the woman who’s now my agent, who then worked with me to sell my first book to the woman who is still (!) my editor: Scandals of Classic Hollywood. My original table of contents was sprawling: there were so many stars, so many scandals (imagined and covered-up), so much to say about how the combination of the studios (who controlled all public elements of a star’s image) and the publicity apparatus labored (sometimes more successfully than others) to maintain dominant ideologies of femininity and masculinity, race, sexuality, and more.

I ended up having to cut about two-thirds of that original table of contents — including one of my absolute favorites of the era: Anna May Wong.

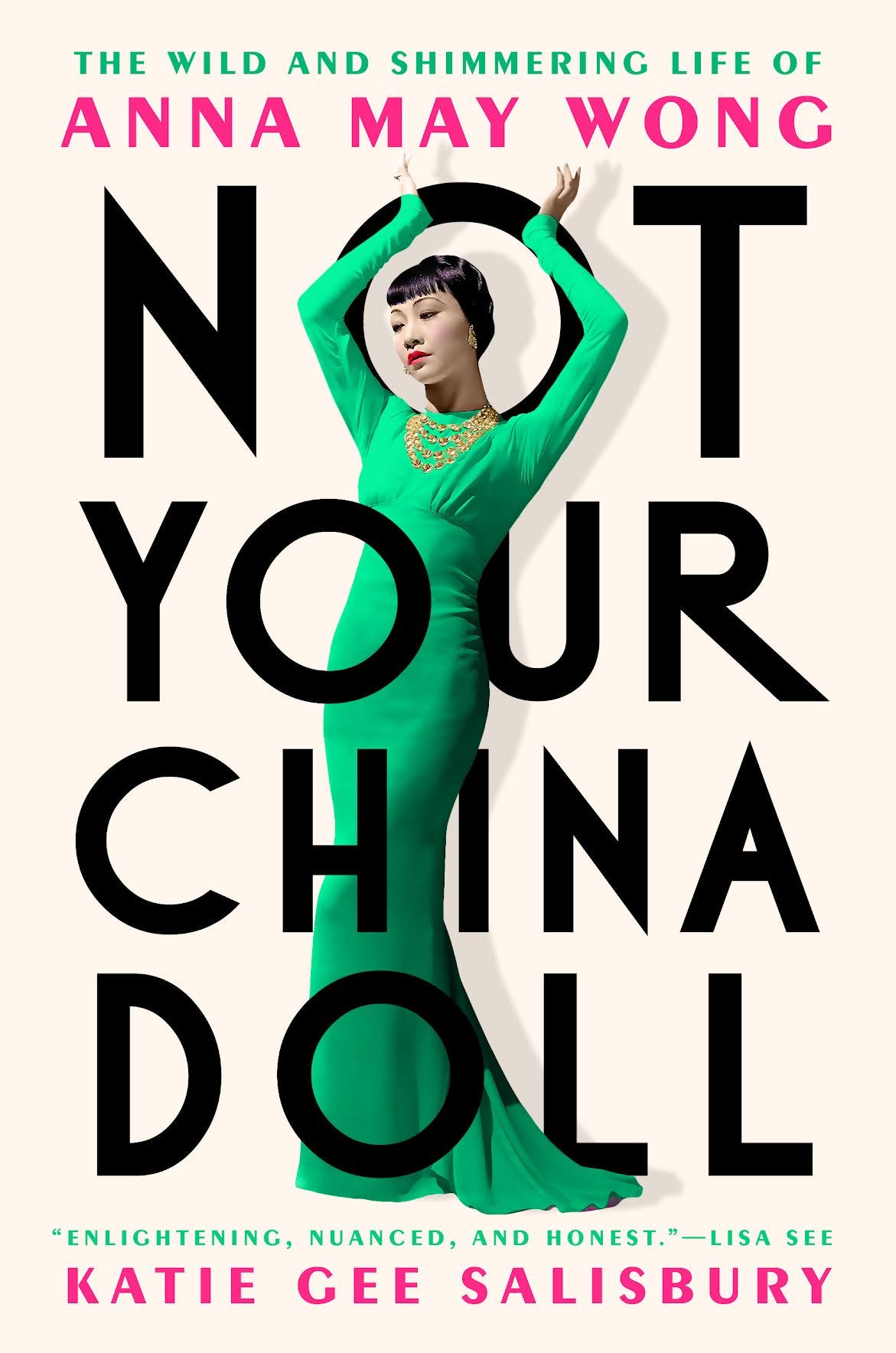

I was truly thrilled when I found out about Katie Gee Salisbury’s new book — not just because it gives Wong the book-length treatment her storied and complicated career deserves, but because it’s really fucking good. It’s hard to toe the line between historical excavation and analysis, establishing your own authority as a biographer but also underlining the ways in which no biography is ever objective — but Salisbury pulls it off.

You don’t have to be well-versed or even ostensibly interested in Classic Hollywood to find this work compelling. You just have to want to think more about how popular media is created, negotiated, and comes to endure — and about the stories those in power tell themselves and others to justify a deeply exclusionary status quo.

You can find more from Katie Gee Salisbury here and buy Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong here.

I’d love to start with the subtitle of your book: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong. I’ve had so many back-and-forths with editors about how to use the subtitle as a sort of keyword search (which often results in very bulky and reductive subtitles) but I love, absolutely love, “The Wild and Shimmering Life.” How’d you get there, and what made it feel like a fit?

In another life, I was a book editor, though not the kind who cared about keyword searches. Which is to say I’ve had a lot of time to think about titles/subtitles! Conventional wisdom says that biographies should be titled after their subject’s name, but that always felt boring to me. Not Your China Doll is a riff on I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s documentary on James Baldwin—and also the words of Baldwin himself. I came up with the title before the book had even been written or sold. I wanted to reframe the narrative around Anna May Wong’s life and career, to give her back the agency that she always had, so the defiant edge of those four words felt right.

For the subtitle, which went through several iterations as I was writing the book, I wanted something that was evocative, that would capture just how radical and thrilling her life truly was. There were a few phrases and titles that I kept turning over in my head. One was The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao—I always loved the title of that book. It made me want to read it.

The other phrase that came to mind was that famous line from Mary Oliver, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?” I liked the possibility that the word “wild” opens up. It can mean so many different things: wild, as in out of control, on the wrong track; or “that’s wild,” as in unbelievable, incredible; or wild in the original sense of the word, meaning free, independent, in tune with nature and oneself. I also did an informal survey of biographies with interesting titles/subtitles, which helped me get it down to the basic formulation “The _____ and _____ Life of Anna May Wong.” Then I played around with various adjectives and tried different combinations. “Wild” stuck.

The missing puzzle piece was “shimmering.” If I had to rank my favorite words, shimmering would definitely be up there. There’s something so vivid and powerful about it, like I can see the way a shiny object glints in the light every time I hear that word. And it fits Anna May Wong’s life so perfectly. Even when times were dark, she still found a way to shine. It also speaks to the fleeting nature of fame and how there can be beauty in a brief moment or scene (whether in a film or in real life) that lives on forever in our minds. The challenges Wong faced in her lifetime, and there were many, could never take away that shimmering quality that only she possessed.

In the section where you outline your research methods, you added something I’ve never seen made explicit as a methodology: your own experience. In your words: “I also drew upon my own personal and familial knowledge of what it’s like being Asian American in this country: how one never quite possesses the feeling of belonging to any single group, a phenomenon I have felt acutely as a multiracial person.”

I’d love to hear more your thinking about the importance of foregrounding this type of familiarity — and how it helps contribute to the general understanding that there is no “objective” history of anyone’s life, particularly not a public figure. This isn’t *the* biography of Anna May Wong, it’s *your* biography of Anna May Wong — which is part of what makes it so good.

You articulated it in a way I hadn’t thought of before, but that’s exactly right. This is my biography of AMW and that’s what makes it what it is. I definitely went out on a limb in the preface by talking about the subjective nature of biography (or of any book or work of art, really). My editor actually wanted me to take that out, I think because she worried it would undercut my authority, which makes sense. But at the same time, how could I pretend that this book I’ve written about another person—a person I’ve never met, who has been dead for more than 60 years—is 100% accurate? Only AMW can say whether it’s all true, and even then, she herself might misremember the events in her own life (just as we all do). And then we’re falling down the rabbit hole into a debate about the nature of truth!

One of the reasons I felt comfortable foregrounding my identity and experiences as an Asian American is that “who you are” is such a big part of the conversation when you’re pitching your book idea to publishers. With nonfiction, editors want to know why you’re the best person to write the book you’re selling. And when you look at the work I’ve produced over the last decade, there’s a clear trend. I’m naturally drawn to stories about Asian Americans and issues related to our place in this country.

I suppose on some level it was also a defense mechanism. Because I’m mixed, many people don’t realize I’m Chinese American and sometimes don’t believe me when I tell them. It’s uncomfortable and something I have to grapple with on a regular basis. But as a result, I’ve spent a lot of time interrogating my identity. While I may not always experience the world precisely as Anna May Wong or most Asian American women do, especially when it comes to the way we are objectified and sexualized by the male gaze, I still live with a constant awareness of that experience—through my family, friends, and community. Reading other biographies of AMW, I always felt that they were missing the perspective of an Asian American woman who has to deal with the triple bind of her cultural heritage, her Americanness, and her gender.

Along those lines — how did you approach primary research materials (like, say, the fan magazines) which “told the story” of Wong’s experience in Hollywood? It was always a difficult process for me when I was researching my first book, which relied heavily on fan magazine archives — I found myself always wondering: what’s at stake with this particular framing? Why would the studios want the star (or the film) to be understood this way?

For each chapter or period of Wong’s life, I pulled as many resources as I could, i.e. newspaper clippings, magazine articles, interviews, correspondence, firsthand accounts from various Hollywood memoirs, etc. Then I read everything and tried to make sense of it. I had to do a lot of reading between the lines with sources like the fan magazines, as you mention, and when sources conflicted, try to figure out what the real story was.

A good example of this is an incident during the filming of The Thief of Bagdad when Wong supposedly refused to put on her “Mongol slave” outfit. A previous biographer had characterized the incident as Wong not wanting to wear such a revealing costume unless the star and producer, Douglas Fairbanks, wrote a letter to her father. But when I took a look at the source material myself, I found it told a slightly different story. The account comes from a New York Times interview with Douglas Fairbanks, who was given to telling tall tales and making things sound sensational for reporters.

According to Fairbanks, Wong got upset when the studio publicist misheard her Chinese name as “Two Yellow Widows” and sent it out in a press release. “It took some time to tell her that it was an error,” Fairbanks explained, “and I finally, even then, had to write a letter to her honored parent before she would agree to put on the Mongol slave costume.”

Now, Fairbanks was a huge star. In fact, they called him the King of Hollywood. The Thief of Bagdad was going to be a massive blockbuster, everyone knew that for certain. So this was a big opportunity for Wong, the biggest yet of her nascent career. The idea that she would walk off the set or refuse to put on her costume because of such a silly flub—“Two Yellow Widows”—rang phony to me. Add to the mix another fan magazine interview I found with Wong where she tells the reporter that people on set made fun of her Chinese name by “kidding the other actors—[who] dubbed Snitz Edwards ‘Two Lots in Glendale’; Julanne Johnston they called ‘Couple of Peach Melbas,’ and things like that.”

There’s no way to know for sure exactly what happened, but I have enough circumstantial evidence to make an educated guess. James Wong Howe, a brilliant cinematographer and one of Wong’s contemporaries, often got called “Chinaman” on sets and some people refused to work under him because of his race. Knowing that and the general racism of Hollywood at the time, my interpretation is that words a bit saltier than “Two Yellow Widows” were flung at Wong. To my mind, only something as insulting as a racial slur would have spurred Wong to boycott production.

Your telling of the saga behind the making of The Good Earth — and the cruelty of the casting, and the shadow it cast over Wong’s career for years, both leading up to and after the film — is the best I’ve read. Can you situate the book and casting and some of this truly fucked up story for readers? [I keep thinking of that incredible Walter Winchell quote: “Funny that nobody thought of Anna May Wong for The Good Earth]

Thank you—I take that compliment to heart! I’m cognizant that some people may read the book and wonder why I’ve devoted so much airtime to a film Anna May Wong isn’t even in. The reason is that whenever anyone talks about Wong’s career, The Good Earth and the fact that she lost the lead role to a German actress is the thing that catches everyone’s attention.

The film was based on Pearl S. Buck’s bestselling novel of the same name, which follows two Chinese peasant farmers, Wang Lung and his wife O-lan, and how they navigate challenges of Biblical proportions like drought, famine, and war. The book was, perhaps, the first to depict rural Chinese life in a sympathetic light for American readers and in a way that humanized the Chinese. Reviewers couldn’t get over the fact that the characters felt so familiar, they forgot they were Chinese.

Irving Thalberg, MGM’s Boy Wonder, was convinced the book would make an epic film, and he similarly wanted to portray the Chinese sympathetically. But here’s where the industry’s endemic racism creeps back in. Although Thalberg briefly considered casting Chinese actors in the principal roles and sent crews to China and up and down the West Coast to audition potential actors, he ultimately concluded that white actors should play the leads in “barely there” yellowface makeup.

At the same time, the production went to great lengths to ensure the film’s “authenticity” by importing whole farmhouses and all their tools from China and hiring thousands of Chinese American extras to work a 500-acre plot of land in Chatsworth. I went through some of the production materials held at the Academy library—the detail with which they documented Chinese hairstyles and dress is incredible. But also incredibly maddening! They were so dedicated to this painstaking level of accuracy, and yet they couldn’t bring themselves to cast Chinese actors in the lead roles!

Reporters speculated over who would play Wang Lung and O-lan, and Anna May Wong’s name came up again and again in various papers and magazines. As the only notable Chinese American actress in Hollywood, she was the obvious choice. But of course, that’s not how things turned out. In the end, they gave the role to Luise Rainer, a new arrival from Germany whose English was only so-so. Apparently, MGM didn’t mind if she had a European accent…but Chinese actors with accents were considered unusable for speaking roles. Rainer later won an Oscar for her performance as O-lan.

This was a terrible disappointment in Wong’s career, but it was by no means the end of her. And what she did next was frankly brilliant. She decided to launch her own counterprogramming—if Americans wanted to see the real China, she would take them with her on her first trip there. She hired Newsreel Wong to film her travels and wrote a series of articles for the New York Herald Tribune documenting her trip. The chapters in the book that cover her time in China and the making of The Good Earth are meant to serve as a split screen. You get to see Wong experience China for the first time and compare it to the China MGM was manufacturing for the screen. There are so many interesting contradictions and hypocrisies that arise from that.

Stick with me for this one, it’s a little twisty. When I learned and later TA’ed for film history, the somewhat pat answer for student questions about why there were more people of color in silent Hollywood was that silent Hollywood was truly global — you just had to translate the language of the titles (if you even needed to do that) and films could travel across the world. That opened up the understanding of potential audience, who was making films (e.g., absolutely not just Hollywood) and who could star in them — which helped lead to Anna May Wong’s silent success, but also Sessue Hayakawa, Dolores Del Rio, Ramon Novarro, Lupe Vélez, just to name the most prominent.

That *relative* diversity ended with the beginning of the sound era and the consolidation of Classic Hollywood over the course of the late ‘20s and ‘30s — some of the stars, like Wong, were able to weather the transition, but others (like Rita Hayworth) were assimilated into whiteness in order to become stars…..and actors in yellow or Black or brown or red face took roles that could’ve been played by stars of color. Global monopoly of the business, rooted in the United States, meant creating stars (and films) that catered to the lowest common (racist) denominator.

You could argue that as the filmmaking audience has once again become truly global, and so, too, has the profile of the leading stars in Hollywood. But I don’t think that understanding sufficiently accounts for 1) the number of roles explicitly written for actors of color that are still cast with white actors; 2) global distributors’ claims that Black movies “don’t do well internationally”; 3) reliance on stereotype when it comes to the types of roles for which studio will cast an actor of color.

Which is a very long wind-up for the question: how has immersing yourself in silent and classic Hollywood shifted how you think of Hollywood, mainstream cinema, and stardom today? What dynamics have changed, and what’s only pretended to have changed?

This is something I’ve thought about a lot. One of the things that surprised me while I was researching Wong’s career was how many other Asians were working in Hollywood at the time. Stumbling upon people like Moon Kwan, Etta Lee, Kamiyama Sojin, and Winnifred Eaton, in addition to well known names like James Wong Howe and Sessue Hayakawa, really astonished me. How come no one ever talks about these people?

I was also fascinated by the ranks of women in early Hollywood who wrote and directed films. For a long time, Frances Marion was the highest paid screenwriter. The argument about silent film being global doesn’t really do it for me either. My working theory has been that women and other marginalized folks had an easier time breaking into films in the 1910s and 20s because the moneymen gatekeepers hadn’t been installed yet. Most people don’t realize that film back then was a speculative medium, sort of like TikTok today. Critics thought it was low-brow drivel that wouldn’t last. No one in the “legitimate theater,” as they snobbishly called it, wanted to be seen in the flickers. It’s like Silicon Valley in the 1960s. Why were there so many more women in the industry then? Because people didn’t know what it was and didn’t ascribe traditional notions of prestige, money, and success to it yet.

But once public opinion began to shift and cinema was seen not only as an art, but as a multi-million dollar business, all the white men closed in on it and pushed the people they didn’t like, who’d been there first, out. Or at least that’s my reading of how the industry became less diverse over time—and then the Hays Code helped codify racial restrictions.

To answer your question, what this taught me about Hollywood is that, unfortunately, very little has changed today. It’s the people at the top who control what gets made and how. Who tells the story matters. People will sometimes make excuses for why Anna May Wong was treated the way she was, i.e. “she was before her time” or “people weren’t ready to see a Chinese woman in the movies back then.”

In my opinion, nothing could be further from the truth. The woman got 500 fan letters a week! Fans, industry reporters, and the directors she worked with all lamented that she was given such lousy parts. A studio head like Irving Thalberg could have made Wong an A-lister if he wanted to, could have cast her in The Good Earth and the film still would have been a hit. (Paramount, for example, made Marlene Dietrich into a star practically overnight; no one had ever seen her films in America when she was signed to a 7-year contract.) But it was his own myopic attitude that sidelined Wong. It wasn’t the people saying “we don’t want her,” but studio heads like Thalberg letting their personal biases dictate business decisions.

The only reason I think this has started to change for Asian Americans in Hollywood today is 1) Crazy Rich Asians demonstrated that Asian-led films can be commercial and profitable; 2) there are more Asians in leadership and decision-making roles within the industry; and 3) the pipeline for independent productions means you can work around Hollywood and still find an audience.

The progress that has been made for Asian American representation over the last few years has been incredible to watch. But this is what keeps me grounded: Anna May Wong was making films from what was practically the very beginning of Hollywood, and yet it took 95 years for an Asian woman, Michelle Yeoh, to win an Oscar for Best Actress. That math just doesn’t add up.

Last one, because it strikes me as important to end on this note: many scholars see Wong’s story as tragic. You resist this reading, and your reasoning shifted something in my brain when it came to thinking about her and so many other stars I’ve studied. How do you ultimately read Wong’s story?

I see Wong as a survivor because she was endlessly resilient despite the challenges she faced. There were many junctures in her career where a lesser person would have simply called it quits. But she never did. Indeed, she was weeks away from beginning rehearsals for Flower Drum Song when she died in 1961.

I resist characterizing her life as a tragedy because I feel it’s a disservice to her legacy and doing so minimizes the long list of things she achieved in her short lifetime. Of course, some of the things she experienced are undeniably tragic, like the disappointment of The Good Earth or her battle with alcoholism and cirrhosis. But that doesn’t mean you throw the baby out with the bathwater.

What I tried to do in the book was situate her career within a larger social context. If you look at her peers, many of them flamed out and died young. People lived hard back then, drinking and smoking like there was no tomorrow. I mean, they came of age during the Roaring Twenties! By comparison, Wong’s career was prolific. She worked in silents and talkies, radio, theater, and television over the span of four decades. She was also part of a first class of Hollywood celebrities who experienced fame on a global level, something that just hadn’t existed in human experience before then. Which means they were ill-prepared for the comedown. We take for granted today the idea that fame never lasts, but for many of these early Hollywood stars, losing their status and good looks was an extremely painful and self-destructive experience.

The other reason is that when we focus on the tragedy, we miss all the good that came out of it. Anna May Wong didn’t get to play O-lan. Maybe the role would have changed her career, maybe not. But what she did as a result of that snub is the real story. She went to China for the first and only time in her life, which brought her closer to her heritage and completely changed the way she thought about the roles she took on as an actress. When she came back to the U.S., she took a stand and publicly criticized Hollywood for casting non-Asians in Asian roles. And guess what? She wasn’t blackballed. In fact, she won a new contract with Paramount. Though the films she made there in the late 1930s were B-movies, she was able to wield her influence over the story lines and that’s how you get groundbreaking films like Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939). In the former, she and childhood friend Philip Ahn became the first Asian American actors to play a leading romantic couple in the sound era.

So when people think of Anna May Wong, I want them to think about all that she accomplished in spite of the tragedies that befell her. Because that’s what true character is—not what happens to you, but how you respond to it. ●

You can find more from Katie Gee Salisbury here and buy Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong here.

ALSO!!! You can see Katie in person on March 14th at The Strand in NYC — and check out the rest of her book events (in Santa Monica, LA, SF, and more) here.

And a quick note to paid subscribers: if you’re not seeing the weekly Things I Read and Loved, it’s because you’re viewing in the app. (For complicated reasons, I put the list in the subscriber-only footer, and footers don’t work in the app. Thanks for your understanding!)

I appreciated the author’s disclosure of their unique position in relationship to this topic and the depth it lends! I’m always surprised how different disciplines have different practices around these things.

In social research we call these sorts of background disclosures by the author/researcher positionality statements.

Likewise, as noted in this interview, not all disciplines or sub disciplines use or endorse them, playing on the differences in beliefs about whether to keep the researcher out of a presumed objective report or to put the researcher in, owing to an unavoidable subjective/interpretive lens.

I often think these sorts of disclosures would be helpful in everyday media like podcast interviews so we know “who you are in relationship to…X”

https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/undergradresearch/chapter/1-2-a-note-on-reflexivity-and-positionality/

This was incredibly fascinating. I know very little about Classic Hollywood -- I had never heard of Anna May Wong 🙈, but I am in awe of her and her strength.

The part about the studio head gatekeepers coming late and closing off opportunities for so many was eye-opening. In some ways that should be what's labeled as tragic - how myopic, fear-based views have avenues to run dominant throughout our culture just because of the wealth and power of these gatekeepers, who arrogantly think they know better than the rest of the population. It's heartwarming to see people like AMW doing all in her power to resist these forces as best she could.

Thank you for such an interesting interview!!