Before this week’s interview, I wanted to draw your attention to the Consistent Money Moving Project. I first heard about it from the great Lydia Kiesling several years ago, and have been part of it ever since. It’s very straightforward: every week, people with a little extra give to others who could use a little extra. No bureaucracy, no hoops to jump through, just money moving to people who really need it. You can read all about the details here, but the TL;DR is that every week I get a Venmo request for $10, and then that $10 joins a lot of other people’s donations. This past cycle, around 200 people donated weekly, and 18 people received between $145-$175 a week. It’s small, it’s basic, and it matters.

If you’d like to sign up to join this cycle, it’s very straightforward — just fill out this Google Form.

Also: for this week’s threads, we’ll be doing two existential whoppers, both submitted by Culture Study Readers: 1) How Do You Know When To Quit (Anything) and 2) How Do You Balance Your Responsibilities To Yourself/Your Immediate Kin with Responsibilities To Your Wider Community, Society, and the Planet?

Not the sort of thing that’s always easy to talk about, but we have a lot of wisdom in this community. If you’re already a subscriber, get ready. And if you want to be part of the conversation — which reliably reaches somewhere between 500 and 1000+ comments — become one today:

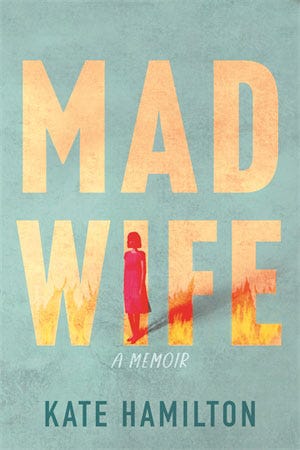

Now, as for this week’s interview — it’s a doozy. Kate Hamilton is a pseudonym for a professor who escaped an abusive marriage — and wrote at stunning, stomach-punch of a memoir about it. I didn’t plan it to align with post-election rage and sorrow, and considered holding it, but you know what? I’m feeling this complicated. I’m feeling this sort of suffocated rage, particularly at the notion that if we, as women, just work harder, things will stop being so abjectly shitty. But if you’re not in the place to read about emotional abuse and sexual manipulation, go ahead and skip this one. It’s not an easy read. But it is a stunning one.

To get us started, I want to go to a section of the book where you describe the plot of Kate Chopin’s short story “The Story of an Hour,” in which Chopin describes the protagonist’s reaction to the news that her abusive husband has unexpectedly died:

“Kate Chopin is a visionary not because she wrote in the nineteenth century a story about a woman feeling reborn at the prospect of freedom from her husband,” you write. “She is a visionary because she wrote in any century a story in which woman who is married to — by her own account — a decent, loving man still experiences her marriage as a cage, a cruelty, a shackling, a structure that granted him permission to bend her.”

You go on to write that this sort of will-bending “is so normalized that an otherwise kind, loving person can commit the violence of denying their partner’s autonomy without being considered monstrous by anyone, both spouses included.” How did this will-bending manifest in your own marriage — and what allowed it to remain invisible?

As I sat down to respond to your questions, secure in my belief that I would be neatly repeating or re-articulating ideas I had already spent years thinking through and rewriting for Mad Wife, this initial question knocked me over. It gets at the heart of the book — which you’d think I’d know well by now — and yet remains somehow elusive, confusing, even stunning to me.

This is the reality of writing about trauma, especially when prolonged gaslighting is involved: no matter how much you piece things together and think through the logic of them retrospectively, the chaos of the lived experience and one’s self-protective resistance to it stubbornly remain.

I think we’ll get to this aspect of the book and the process of writing it later, but I wanted to start by reflecting on how every return to these questions and experiences requires a certain amount of reprocessing and re-experiencing of trauma, and can only be done through that challenging lens. The reality of that fact is something that anyone who’s doing or planning to do this kind of writing should keep in mind. Now, to answer your first question:

Many years ago, when I was still finding ways to believe I was happily married, my then-husband and I were visiting back home with my parents, my sister, and her partner, and we all played one of those board games in which players have to guess things about each other that range from quirky to uncomfortably intimate. One question asked whether I or my husband “wore the pants” in the bedroom—who was dominant in our sexual relationship. Everyone at the table but me threw down their guess cards immediately: they were all certain that I was the dominant one. They were shocked when I revealed my contrary answer. “But you’re in charge of everything!” my sister protested. “I just assumed that…”

Their guesses were based on plenty of evidence: I was hypercompetent and organized and in control of everything visible—family plans, decisions about the kids, every infernal detail of the house we were building, and on and on. I remember being a little shocked to have to admit to myself that night that “in the bedroom” I felt absolutely no control over this aspect of my life and self and body. That was probably the first time that, for an inadequate flash of a moment, I considered the vast difference between the amount of power—and responsibility—I had over all domestic aspects of all four of our lives and the lack of power I had in our sexual relationship. The game moved on, as did my attention. I didn’t really ask myself how I was being “bent” or what allowed my husband to bend me to his will for many years—until I started writing this book.

That board-game question pointed to the most important and painful way I was being oppressed by my husband: he routinely manipulated and pressured me into submitting to unwanted sex for many years in our marriage, under the guise of asking me to express my “love,” which for a long time I truly wanted to provide. The more I thought and wrote about the disastrous end of my marriage, trying to understand it and especially my own seemingly inexplicable behavior during those last terrible three years, the more I understood and was able to register the profound impact of being denied personhood in this way by the man I had spent most of my adult life with and who claimed above all else that he loved me dearly.

I was disgusted at his use of me—sometimes I felt sick during or after sex—but only way deep down, where I could not identify these feelings, much less understand why I felt them. And I was also unconsciously furious with him for his selfish use of me, his inability to acknowledge or care for anything about me as much as my sexual availability to him, to no longer want to connect in any real way with me, to only need my body.

I grew to truly hate him. But I can only see this now, in retrospect. I couldn’t let myself see that at the time, or even for years after I left him. I had wanted so badly to have a loving marriage. We had had one for quite a few years. I had worked so hard to maintain it and to try to get it back, as his ability to connect with me emotionally faltered and then disappeared, while his insistence on our sexual relationship remained. These changes and losses were too painful to take in while I was fighting to recover from them: that his love for me had become so shallow and mean was an unbearable thought. That my love for him had turned to revulsion. And I would not consider leaving, for reasons I explore in the book, so in my mind I was stuck. I could not live like that while seeing how I was living, how he was bending me.

Anyone who will manipulate someone into something so dark and cruel—submitting to sex they demonstrably don’t want, for years—will manipulate them in any number of less vicious ways as well, of course, and he did that too. So part of my story is specific to a kind of personality (whose diagnoses I can only guess) that excels at getting what it needs from others through invisible exertion of power and coercion. As Kate Manne argues in Entitled, this is the dynamic not just of narcissists but of patriarchy in general, which means that male narcissists (and especially the most powerful of them, wealthy white cis het male narcissists) can aggregate and wield incredible amounts of invisible power.

Living in intimate relationship with such a person—who is likely to be lauded by everyone you know, and the community in general, as “so kind, generous, wise,” etc—is confusing and dangerous. You can’t see the subtle manipulation in quotidian interactions, how you’re being brought around to his will through pressures and appeals that are carefully calibrated to work on your particular psyche and his long experience of you. If you tend to be a caretaker and peacemaker, if that’s the role you played in your family of origin—on top of having been socialized as a woman!—you’re particularly vulnerable to these appeals and machinations.

There’s a way in which Mad Wife is also a portrait of what it’s like to be in long-term intimate relationship with this personality type, especially in a heterosexual relationship in which patriarchy exacerbates a man’s power and entitlement. So I’m talking about these kinds of banal exertions of will and “bending” of others as well. I think these less profound forms of manipulation lay the groundwork for the more damaging forms, though, so they are all of a piece.

Why did his manipulations and oppressions remain invisible? Because in our patriarchal society of male entitlement to women’s care and love, however we or they define that, such machinations seem normal. They are more sustained and sinister versions of the ways men pressure us to care for them in various ways our whole lives. They feel normal to us, and we stay in place and suffer them to their painful peak, like boiling frogs.

Throughout the book, I can tell you really grapple with the notion of perspective, the unknowability of truth, how the hero in one person’s story could be the villain in another — which all makes sense given your background in postmodern lit, but also adds a layer of self-interrogation I don’t know that I’ve seen so explicit in another memoir. What was most harrowing about trying to write with this awareness? And what did attempting to rely on the “record” (notes, journal entries, emails) help or hinder when it came to arriving at your own understanding of truth? What does it feel like, as you write in the conclusion, to realize that you had “the right to my own story of my life”?

You’re very right that to some extent I could not write in any other way, because all of my academic teaching and writing come out of an awareness of and belief in postmodern and poststructural ideas about the impossibility of a singular truth or point of view. When writing a memoir like this one, in which I know that others out there had very different experiences and would tell entirely different stories about the same years, it was especially important for me to start from that understanding: this story is entirely and only mine. Others relevant to the same time period and events exist. Paramount to me in writing this book was being entirely honest, sparing nothing of myself (I did attempt to spare others if the details would be hurtful but not crucial to the work I wanted the book to do), in an attempt to say something true. Being truthful starts with acknowledging that the truths are my truths.

My perspective is shifting and multiple so that I can show my writing self looking back on my earlier self, reassessing now my understanding of experiences then, illustrating that I still understand and experience most of what I describe in this book through multiple points of view, as multiple selves who felt and think about these things differently. But it was also motivated by my shame. This is a difficult thing to write about. I’m still working on what I think about that shame—which parts of it I still deserve, which parts I can let go of, and whether any of it is actually useful. I suspect I will be working on this for a very long time. But I can say that my sense of my own shame around the things I write about has changed dramatically through the course of writing this book. I know that in part because close friends who read the first draft or two told me outright that I beat myself up too much, which was neither appropriate nor useful for the reader.

The first draft of the book, in fact, was basically a massive confession. Back then I was calling it Testimony. I needed to confess to all the terrible, shameful things I’d done, alongside trying to understand the painful things that had been done to me. I still carried around worlds of shame my husband (and others) had implanted in me. I saw myself as largely responsible for all of the pain and damage I document in the book. In short, in the first draft I mostly told his story, the story he had implanted in me. It took a lot of rewriting, reflection, discussion with good friends, and consultation of that record you mention—emails, court documents, etc—to begin to see how self-serving his story was, and how factually untrue. So that is the enormously important effect of the records I consulted: they helped me see how much of the story I had been carrying around was simply false.

In thinking about the role of those documents in my ability to understand my story and tell it, I’m reminded of the woman in that last, harrowing episode of Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult at Sarah Lawrence. As she reads aloud from journals she wrote while under her gaslighter’s sway, she struggles to recognize the gap between that younger woman’s distorted reality and her present, and to connect the different selves that lived in those disparate worlds: she needs to write a less fragmented narrative of herself.

Her struggle is heroic, and the fact of it demonstrates her healing. Her contorted face and skeptical eyebrows, her tears over a decade later—everything else demonstrates the lasting effects of trauma that rewriting can’t erase. I’ve emerged from the writing of Mad Wife feeling much the same: I had to confront my earlier selves and their experiences and perceptions, as well as whatever evidence I had of things that really did or did not happen, what exactly was said and done, etc. Doing so helped me clarify a lot of things. It also clarified ways in which some of this refuses to be clarified, still.

I also have to give a shout-out to my amazing agent here, as her insightful questions and comments on several drafts were crucial in the process of transforming my self-flagellating confession into a more clear-eyed account of what happened and what that means for me and for women in patriarchy. At times, she’d express disgust or anger about something I had described neutrally, or even as something I felt responsible for. Her anger on my behalf pressed me to look again at what was really going on in these moments, their causes and inherent power structures, how blinded I still was by shame or simply confusion.

So another motivation for the book’s complicated perspective was my desire to communicate these many acts of reflection and re-vision, to communicate that neither my experience of all I describe nor my experience of writing about it was ever neat or linear. Understanding it required bringing myself back and back to it, to my memories and to the piece of writing. This multiplicitous engagement with the material was integral to my ability to understand or write about it at all. And this formal approach communicates something crucial about how all of these experiences live inside me: I will never stop going back to them, revisiting them with my changing self. I don’t think they will ever be fixed, nor will I, nor is anyone. These things are true about all experience and self, but never more so than for traumatic experience and traumatized selves. I wanted the book to communicate something of that.

I see the Epilogue as key in articulating the largest aspects of this complex multiplicity. In my mind, this book is not just a story of abuse, or of all the invisible avenues such abuse can take, or of my working through that and emerging stronger. It’s a much larger story about confronting what felt at the time like nearly unbearable emotional suffering, and enduring seemingly endless cruelty (toward myself and my children), and deciding how I was going to let all of that shape me—that I was not going to let it make me bitter, small, and mean; that I wanted to use it to become more compassionate, generous, and loving. What enabled me to even think in these terms, let alone experience some measure of success in my endeavors, was a combination of Buddhist teachings and yoga and meditation practice. I list Tara Brach’s website in the “Resources” section at the end of the book because listening to her podcasts about self-compassion and loving kindness while I was enduring the worst of the post-divorce years helped get met through them and transformed how I allowed them to shape me. This larger story of compassion through suffering is also the story of Mad Wife.

And part of that for me is, as I say in the Epilogue, continuing to acknowledge and truly take in, to feel and empathize with, others’ experiences of the events I describe in this book: my ex-husband’s, my former friend’s. Their stories of these events are real and true for them, and I deeply hurt them, and I will not forget that. At the same time that I assert my right to my own story, I remember that my ex-husband has his own sad story, his own history of parental neglect that in part led to the devastating story we would wind up living together. I remember who he was before our terrible years, when we truly loved each other. I know he does not and likely will never understand my experience or acknowledge how he damaged me. We will never share a story of our long history together, during which we created two human beings. That is a tragedy. It makes me sad, not furious or disgusted. It points to all that needs to change about our patriarchal society and the way that patriarchy damages everyone. I think real change can only come, and we can most productively fight for it, when we do our best to hold these complicated, paradoxical truths in our minds, all the varieties of hurt and their many origins, when we refuse to fall into the cartoonish ease of black and white.

To protect yourself and your family, you use a pseudonym for the book — a move that initially felt like a cop-out to you. But your partner reframed this beautifully for you: that it’s “not another self-sacrifice or silenting, but an act of compassion. Compassion that is not cowed.” I’d love to hear you speak more about how that feeling of compassion has grown, or how you’ve continued to struggle to feel it, particularly as the book has come out into the world.

I hate having to publish this book under a pseudonym! It took a lot to write this mortifying story, let alone consider releasing it into the world. Once I was able to do those things, I really wanted to own it. A big part of what this book has done for me is give me a way to integrate my painful, confusing, embarrassing/shameful (whatever I’m calling it today) past into my current life, to make my history and sense of myself less fragmented.

No one in my life, with the exception of my partner and a very few close friends, knew anything about all I write about in Mad Wife. I was a professor, a friend, a daughter, a sister, a class mom and carpool driver, and none of the people I was interacting with or in relationship with knew that I was also engaged in a transgressive and confusing sex life, that I desperately wanted to leave my husband, that I was suffering, that I was suicidal. Later, none of them knew I was writing a book about all of it. It was this huge, dark, secreted part of my life, and the more clear-eyed I became about all that had happened, the healthier and less punishing my sense of myself became, the more able I felt to talk about it, and the more I wanted to talk about it. At this point, having produced a book I’m quite proud of as an intervention into patriarchy and as a piece of writing, I want to shout about it from the rooftops!

I also desperately want to share this story with specific people in my life. One of those is my former mother-in-law, my ex-husband’s stepmom. She’s a therapist who must encounter with her patients aspects of the things I suffered at the hands of her son. She loved me like a daughter, and I admired her tremendously. But she rejected me absolutely the moment I left her son. She never asked me what happened and has not spoken to me, even going out of her way at my kids’ events to avoid me. I dreamed about her rejection of me for years. And I still fantasize about leaving a copy of Mad Wife in her mailbox. I want her to understand what her son did, that I was harmed, that I did not just summarily betray him and his family, and that her rejection of me remains very painful—and, I think, undeserved. But of course I can’t do that, for the same reason that I can’t put my name on this book: the risks are real and enormous.

The best defense against a defamation accusation is having told the truth, and I have. But in court, whose truth is the truth? How can I prove that all these things happened as I say they did, when most of them happened without witnesses, and none of them happened for my would-be accuser in the way that they happened for me? I’ve been in court with this man and seen his totally unsubstantiated fantasy win out over my substantiated truths. I will not test that system of “justice” again, or willfully provoke a suit that will land me in it or all of its ugly fallout—for myself and my children, who I do not think are in the right places in their lives or development to have to process all that this book will one day make them process.

But selfishly, I also look forward to sharing this book with my children when the time is right for them. It’s been very hard to swallow all I’ve had to swallow to support their dad in his uneven, often neglectful, at-times abusive parenting. It’s been very hard to watch my sons forget all that—more likely, repress it—so they can now have “healthy” or at least functioning relationships with him. I’m glad they have found ways to preserve their relationships with him, and that he has, they tell me, changed how he treats them considerably. But allowing them to set all that aside, and not sharing with them all the other ugliness of our marriage, which is of a piece with my ex’s selfish treatment of them, leaves me alone in the truth of our family. That can feel like another form of gaslighting. So sheltering them from these truths at this point is an act of compassion for them.

It is also, of course, an act of compassion for my ex. If I thought he would understand and reflect on my story, if I thought he would learn, if I thought we could finally exchange sincere apologies, if I thought we could thereby find a way to a less toxic relationship, I would share my book with him, roll up my sleeves, and do that very painful, difficult work. But everything in my experience of him tells me that this book will inspire only rage in him and danger for me. And it will embarrass and hurt him, to no productive end. So most of the benefit of what would come from putting my name on the book would come to me: public acknowledgment, self healing, professional credit for publishing a memoir. And much of the suffering that would come would impact others: my children, my ex, his family.

But there is one important way that using a pseudonym actually hinders me from helping others: I can’t share the book with his many ex-girlfriends who could greatly benefit from it. Two of his former girlfriends have approached me in public—one in a hair salon, one on a hiking trail—and asked me to help them make sense of what he did to them. How desperate do you have to be to do that? I recognized the particular blend of confusion and pain on their faces immediately: they looked as if they’d recently been expelled from a cult or hostage situation. Their stories were eerie echoes of mine, though briefer and with fewer salacious varieties of suffering.

One stopped me on a ridge trail and described a humiliating incident so similar to my own, and in the same space of the house I once shared with him—the basement guest room, where he banished me when I asked him to stop guilting me into having sex with him—that I almost told her about Kate’s memoir on the spot. For miles after we parted on that ridge, headed in opposite directions, I agonized about it: this woman who could not fathom the gaslighting magic that got her compliance and still blamed herself for submitting to his use of her was exactly the kind of woman I wanted to read Mad Wife. If the book could change anyone’s life, lessen anyone’s pain, it would be hers.

But I never told her about my book. And when I was asked about it by a friend who wanted to direct another of his exes to the book, I had to beg her not to talk about it. In these moments, the awful irony of the unchosen pseudonym becomes clear: it gives “Kate” a way of coming to voice and a platform for sharing her understanding with the world, but it prevents me from expressing my empathy and support to those who need it, who even come to me asking for it, right here in my real life. This includes more than his gaslit ex-girlfriends, to whom my heart goes out. As a college professor and scholar working on feminist topics including patriarchal power and sexual abuse, I encounter women of all ages who might recognize themselves in my story and take comfort from it. Every time I choose to tell one of them about Mad Wife I risk significant harm to myself, possibly my children, and to the book’s ability to get into hands beyond those in my small circles. It’s the trolley problem in reverse: whose suffering do I choose to address and whose do I ignore? What ethics guides my choices?

A recurring theme in the newsletter is that high-achieving women are conditioned to think of relationships as work, which means that if they just work harder (at counseling, at communication, at motherhood, at sex, at listening) things will….work out.

I’d argue this thinking is elevated for people in academia — even as we study theory that encourages us to think about much larger systems largely immune to individual action, we still think (especially in the time period when you were in the throes of your marriage) that individual grit and labor will lead to success. Did you feel that compulsion to keep working on your marriage, even when it turned repulsive and terrifying?

I think — I hope—my tireless efforts to fix my marriage will become clear to readers of Mad Wife, as will the ultimate damage caused by my belief that enough of my hard work (and mine alone) could fix it. So much therapy, and books read, and theorizing, and conversations, and date nights spent debating our ultimately incompatible ways of understanding our problems and hoping to salvage our marriage — and all of it resulted only in years of abject misery.

We worked with several therapists over several years and across three states. None of them said “you are damaging each other” or “this is an abusive marriage” or “you have long since hit an impasse.” I do resent those therapists, deeply, for not having the courage or the proper training or simply the ethics to say that. In my experience, couples counseling was primarily another method for ensuring that people stay married, an ideological tool for upholding the presumed good of marriage at any personal cost. Not one of those therapists recognized the manipulation that was happening, or that our sexual relationship was seriously damaging me (though I said as much in front of one therapist and my husband), or the patriarchal entitlement that imbued every aspect of our dysfunctional relationship. Not one of them recognized or acknowledged that only I was trying to fix our marriage, while my husband was using therapy, along with everything else, to get his way. I do blame that string of therapists for prolonging the misery and enabling it to escalate by normalizing all of the abuse.

We also need general acknowledgement in our culture that broken, dysfunctional, toxic marriages need to end. I write in Mad Wife about the interesting mix of celebration and blatant acknowledgement of suffering that surrounded my parents’ 50th wedding anniversary party. Certainly all long relationships are difficult, require hard work, and entail a certain amount of suffering. As Zadie Smith once wrote, “Generally, we refuse to be each other.” Relating long-term to another who wants to love you but cannot be you always involves sacrifice and a certain amount of pain.

But my parents’ marriage was, for most of my life, enormously unhappy. I grew up in a house full of screaming, tears, rage, and disappointment. I saw that my mother would never leave. All those years later at the party, I watched as we all celebrated that — her never leaving. Her staying despite years of suffering. At this point, I believe she’s glad she stayed; my parents have reached a kind of separate peace near the ends of their lives. And I am grateful that I still have them both in my life and that these last years of my family of origin are — at last — happy ones. But the damage was done long ago. I absolutely could not entertain the thought of leaving a situation I absolutely should have left, because everything in my life told me not to, I had no right to, it would be a failure to, I had no good reason to, and that marriage is suffering and yet you do not leave.

I did feel like a failure when I left. But now, I’m proud of myself for finally allowing myself to wrench myself free. I have taught my children something precious: that marriage and family should not be about suffering. That partners should not oppress each other, that children should feel safe and loved, that parents and partners should not be screaming and crying because they can’t stand to be with each other but can’t stand to leave. I’ve given my sons—at least for most of their lives— a family where they can see this kind of genuine love, companionship, and mutual respect governing every day of our lives, and they can learn how to treat others and be in intimate relationships in these generous ways. I wish our cultural images and couples counselors would aim to model and expect the same.

What feels most provocative about the book — and what conversations do you hope it starts?

The very act of contemplating which elements of the book I think are provocative, versus what might be considered provocative by my feminist agent, editor, or colleagues, or by my (politically and socially conservative) parents, or by general readers, points to the complicated ways in which Mad Wife intersects with cultural norms and expectations around gender and sex, and how those will differ for people with different values or experiences, or of different generations.

I have already encountered examples of such differences — which are really differences in how able we are to see misogyny and how committed we are to fighting it — in the process of producing this book. I saw the limits of my own awareness when an early reader expressed outrage about an incident that I had taken in stride, pushing me to step back and see the misogyny that I could not see when I lived it. And I saw the limited awareness of a young “feminist” student, who could not see the misogyny in her own response to me when I spoke about unwanted sex for a class on domestic abuse.

That’s the intellectual answer. But when you ask me what feels most provocative — which is a way of asking what feels most risky, what risks provoking the most intense and possibly painful response from readers—I have several answers.

I never call my experiences of unwanted sex in my marriage “rape.” But I do illustrate the many similarities between my experiences — both in the moment and for years afterward—and those of women who have written about suffering what we would unequivocally call “rape.” I also compare my experience to the kinds of sexual violation we have loudly and widely condemned when it happens in dating scenarios, especially since the 2017 viral spread of Burke’s “Me Too.” To date, no major publication or voice has talked about these similarities, or how common submitting to unwanted sex in marriage is, or how destructive it can be to women and to marriages. I want to start a conversation about that, perhaps most of all.

I’d also like to add another facet to our ongoing conversation about women’s desire. Books such as Tracy Clark-Flory’s Want Me: A Sex Writer’s Journey into the Heart of Desire go a long way toward recognizing the many cultural pressures that shape and distort our sense of what we desire, and the pressure we experience to perform desire we don’t feel. In Mad Wife, I’m very honest—some might say excruciatingly so—about many kinds of sex I had, asking myself whether I chose each sexual encounter, whether I desired the sex I was having, and why I often chose to have sex I didn’t desire. Essentially I’m asking, is choosing to have sex without desiring it a real choice? I can imagine that in some situations—say, in a truly loving, mutually respectful relationship, in which one is not feeling bullied, manipulated, or eradicated—one might say that it can be. Books like Desire: An Inclusive Guide to Navigating Libido Differences in Relationships (by Lauren Mersy and Jennifer Vencill) aim to help couples make exactly such determinations, to find ways to deal with differing sexual desire while always prioritizing a couple’s real intimacy and each individual’s right to make their own sexual decisions. But as I explore in Mad Wife, it’s not just in long relationships that women feel pressured to have sex we don’t want. We find ourselves in such situations in a depressing variety of contexts. Often it’s easier to give in than to assert what we actually want or don’t want (I think of Kate Roupenian’s fantastic story “Cat Person” here). What would the world look like if women only had sex when we truly desired it? What would it take to make a world like that? Those are provocative questions I hope my book is asking, and conversations I hope it will start.

Likewise, we’ve seen quite a few publications about ethical non-monogamy in recent years; I reference a few in my book. So that conversation is starting. But I think we need to be careful and clear-eyed in how we talk about ethical non-monogamy in its many forms. Early this year, a memoir called More sought to propose open marriage as a kind of whiz-bang solution to a couple’s desire for a more exciting sex life. The book jacket says it is about the author finding “self-fulfillment” and “becoming her most authentic self.” Yet the book is painful to read, because it tells the exact opposite story—not of a woman pursuing and fulfilling her own desires, but of a woman desperately trying to have as much fun having sex with other men, who treat her horribly, as her husband clearly is having while having sex with other women. But what she mostly finds is emptiness and humiliation. The fault of course is not with open marriage itself, but with how she and her husband go about it, and how little either of them care about her real desire. I write a good deal about my experiences swinging with my husband—not because it’s sexy, or salacious, or liberated, or part of my “journey to self-fulfillment.” I write about it because swinging was another kind of sex my husband pressured, guilted, and manipulated me into doing. And it became another way he could control me while we told ourselves we were both being transgressive and free.

Making my swinging experiences even more confusing, some things I did while swinging I actually enjoyed, even if I did not go into them desiring them. The difference between “enjoying” and “desiring” is subtle and complex enough—perhaps more dependent on time and context than on feeling—to make my point for me: it’s very hard to know myself what I mean when I say I enjoyed elements of things I did not desire. What does it mean that the world of swinging, into which I felt forced, became a place where I felt powerful, where I felt I choice had been given back to me? Where is the power in choosing among things that have been chosen for you? Was I liberating myself by turning a site of control into an opportunity for pleasure and power? My experiences swinging raised these questions for me, but these questions do not exist only in the world of swinging. I would like for my book to start these conversations.

Finally, the most painful part of the book for me, and possibly the most provocative (which may depend on whether readers feel I express the proper amount of regret about it), is the role of extramarital affairs in the end of my marriage. Of all the things I wrote about in Mad Wife, this is the one I won’t try to sum up here or anywhere. No pithy thing I say about it can do justice to the complexity of my experience or my thoughts and feelings about it, while anything I say is likely to open me up to all variety of excoriation. I hope people will read the book on this point. But what I can say here without dithering is that the extra-marital relationships I had near the end of my marriage, when I could not leave but could not endure the dehumanizing state of my marriage and was considering suicide to escape it, saved my life. They made me feel like a person again. Engaging in them didn’t feel like a matter of ethics, but like air feels to someone on the verge of drowning. Still, while they saved me, they hurt others, including a close friend, and writing the book required me to really face that fact, sit with it, and understand how I had become a person who could do such a thing. This was perhaps the hardest and most important work I did for myself in writing the book. I can only guess at how readers will encounter that work, but I can tell you what I learned for myself, and what I hope others will get from it.

People do terrible things when they feel they will otherwise die in some real way. That doesn’t excuse those terrible things, but it should explain them as not merely “immoral” but as existential acts. Moral threats are easier to resist than are existential ones. I get that now, just as I see that I’m not above falling apart in spectacular ways under the right pressures. This is one of the important ways that the painful end of my marriage changed me for the better: in discovering my limits and flaws, in failing, in becoming for a time the worst version of myself, I realized that what had previously separated me from all those who have failed in significant ways was not simply my hard work and ethical determination coupled with some innate “goodness.” It was some of these things but also it was circumstance, or what philosophers call “moral luck.”

One of the most important results of all that I write about in Mad Wife is that I was profoundly humbled. My instinct now is to empathize with and support others rather than judge. So there are two more conversations I’d like my book to augment: one is about how we think about and address the ubiquity of extramarital relationships, and the other is about how we might all find it in ourselves—even without having to see our lives fall apart—to be a little more compassionate with others when they stumble. To see the suffering rather than the failure.

Overall, I think what people will find provocative—and the nature of their responses to the difficult topics I write about in the book—will depend on how much they care about women’s rights to autonomy and self-respect, and how able they are to see the things in our culture that deny us those things. It will also depend on readers’ sexual ethics. And it will depend on their ability to encounter me and my story with the compassion that I try to express for everyone I write about in Mad Wife. ●

You can buy Mad Wife here.

Your subscriptions are what keep the paywall off posts like this one, which make it possible for everyone to read and share the work of authors you might not otherwise encounter. If you value this work and want to keep it accessible, consider subscribing today.