Are you one of those people who keeps saying “I should sign-up to be a paid subscriber” and then because you’re on your phone or you get distracted or you forgot the code for your credit card you just….don’t? I get it; I do this all the time, but I’m trying to be better and more intentional and actually pay for the things that I really value. If that’s you, too, consider becoming a paid subscribing member. You make work like this possible.

ALSO MY PODCAST, WORK APPROPRIATE, IS HAPPENING!! I’ll be writing a lot more about it soon, but every week, me and a new cohost/expert will attempt to answer your workplace quandaries, on everything from toxic non-profit culture to what good virtual management might actually look like.

It launches Wednesday, October 26th from Crooked, and if you don’t want to rely on me reminding you that it exists, I strongly suggest subscribing to it wherever you listen to your podcasts (click here for Spotify then press “Follow”, here for Apple Podcasts, here for Stitcher) and then wait for little presents to start appearing in your feed every Wednesday. Oh, and here’s the trailer!! Plus you can submit your own work quandaries anytime at WorkAppropriate.com. This has been a full year in the making, and I’m really proud of it — and can’t wait to hear your thoughts.

AHP note: This is the (right on time) October Edition of the Culture Study Guest Interview series. I interview people nearly every week for this newsletter, but my inclinations and passions are, well, my own. If you have a pitch for an interview with someone who is not famous but writes or does work on something that’s really interesting, send it to me at annehelenpetersen @ gmail dot com. Pitches should include why you want to interview the person, 4-5 potential questions, the degree of certainty that you could get the subject to agree to the interview, and have CULTURE STUDY GUEST INTERVIEW in the subject line. Pay is $500. This month’s interview is conducted by Colleen Murphy — who you can read more about at the end of the piece.

I’ll also quickly note that when I first read some of the ideas here, I balked. Not because they aren’t good, but because I’m so used to thinking of what academia has *not* been able to accomplish and how precarity disincentivizes change. There are reasons why I’m inclined to think that, based both in my experience but also my peers’ and my parents’ experience in public higher ed, particularly in a state whose legislature would gladly eliminate it altogether. But I also have to remember that you can’t create change if you can’t think it, can’t imagine it, can’t articulate it. I realized: I have to allow myself to imagine what this hopeful futurism would look like. I hope you allow yourself, too.

One of the best feelings as a reader is coming across a book that challenges my thinking, and exposes me to ideas I hadn’t considered before. This was how it felt reading Universities on Fire: Higher Education in Climate Crisis, a forthcoming book fromher education futurist Bryan Alexander.

I first interviewed Bryan a few months ago, and even though climate change wasn’t the focus of our conversation, I was captivated when he led us there. Despite spending years reporting on higher education and editing policy journalism, I had yet to see someone lay out the reality facing colleges in this way. As Bryan describes it, the climate crisis is already here — and if colleges aren’t already grappling with it, they need to start.

I got to read a draft copy of Bryan’s book for this column and tore through it. It explores how colleges can respond to the climate crisis, and highlights dozens of unique approaches , including the types of interdisciplinary courses faculty could teach and how college campuses could be redesigned amid increasing temperatures, raging wildfires, and rising sea levels. Despite being neither a climate change expert nor an academic, I found it accessible, engaging, and —perhaps surprisingly, given the topic — energizing.

Universities on Fire is slated for a March 2023 release. Pre-order a copy here and follow Bryan on Twitter here.

**This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.**

Let’s start at the very highest level here, to set up our conversation. You’re a higher education futurist. First off, what does this work mean to you, and what inspired you to pursue it?

Being a higher education futurist means I help people think more strategically, creatively, and effectively about academia’s future. “People” are all kinds of people within academia, from presidents and boards to professors, librarians, students, technologists, and others, in addition to people outside the academy who work within it - i.e., scholarly publishers, educational technology companies, government officials working on post-secondary education, foundation officers, etc. Helping them think this way involves a bunch of things, from writing books like Academia Next to giving talks and workshops, hosting weekly video conversations, and teaching Georgetown University graduate students.

Several things inspired me to do this work. First, in the early 2000s I worked for a nonprofit organization focused on helping small colleges grapple with the digital world. I researched emerging technologies and helped these campuses collaborate on them. Over time I found my work expanding beyond technology per se and starting to include other domains: the complex politics of the higher ed ecosystem, the role of public policy and cultural attitudes, demographics, macroeconomic trends, and more. Thinking through all of those fields in terms of emerging technology — that’s exactly what professional futurists do. I threw myself into that field and found it both productive and rewarding for my own work.

Second, I found that if I spoke to academics in terms of technology, I’d lose a significant amount of audience. But if I framed my presentations in terms of higher education’s future more broadly, including but not limited to tech, everyone was engaged.

Climate impacts are a certainty — from fires, to rising sea levels, to higher temperatures. But what isn’t locked in yet is how colleges respond. You describe lots of potential future scenarios, such as professors reining in long-haul conference travel or universities hosting climate refugees in residence halls. But you also note that while higher education isn’t known for being home to climate-change deniers, many academics haven’t been focusing on the climate crisis thus far. What action do you hope this book inspires? And what is the main takeaway you want readers to have?

I hope readers start thinking about the many ways the climate crisis and higher education intersect and acting upon those thoughts — quickly. This is not a simple equation, but one with many variables and dynamics.

We can divide the intersection into several levels. On an immediate level, some physical campuses face physical threats from climate change (flooding, desertification, dangerous levels of heat) and need to determine how to protect themselves. As the crisis widens and its second-order effects appear, all campuses regardless of their physical situation will have the option of aiding their colleagues through physically hosting endangered students, faculty, and staff, or providing digital teaching resources, or scholarly support. At a different level, I hope this book inspired faculty to expand their climate research and teaching across the curriculum, from Earth science to economics and literature.

These are internal levels, if you like, occurring within the physical and institutional boundaries of a college or university. But campuses also play a role beyond their walls: they exist within a larger community, be it a city or town, and have many ways to connect about climate issues. Will schools provide cooling shelters for their neighbors, or draw electrical power from municipal hydro? Climate-caused economic and social changes can roil a community; an embedded campus would have to decide how to react. As communities take larger steps to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis, colleges and universities may participate in them. For example, students and faculty might assist with building a seawall against rising waters.

Academics can play a role on the world stage. Faculty as well as staff and students can act as public intellectuals, seeking to inform and influence societies and governments about the crisis. The world, of course, also informs and influences campuses. As the climate crisis develops and nations respond, their policies, ideologies, and cultures can impinge on academics even behind the supposed ivory tower. Large-scale mobilization, reactionary denial, new economic models like degrowth can strongly impact colleges and universities. Academics have the potential to use their institutional, intellectual, and community capacities to engage the crisis.

As is often the case in higher education, some of this seems easier for the richest universities. For example, you write about how colleges could design new buildings or relocate campuses entirely to avoid rising sea levels. But, climate change aside, there are also many institutions struggling financially, and many colleges already have a backlog of campus construction projects.

How will climate change further exacerbate the “haves and have nots” in the higher education system? And, how is that playing out already? (Also, side note: I loved the idea of ranking colleges and universities by their climate resilience, as Anand Kulkarni of Victoria University has suggested.)

The climate crisis may well make the academic rich richer and the poor poorer, a kind of academic-climate Matthew Effect. The wealthiest institutions clearly have greater resources to expend on any number of climate strategies compared to the least resourced schools: community colleges, underfunded state universities, financially weak private colleges and universities. Publicly funded institutions may suffer additionally as national, state, and provincial governments struggle with climate-driven economic problems. We can see some signs of this in the leading role played by leading research universities in climate research and communication, such as Oxford and Yale. In the United States we can also see rising conservative dislike of academic uniting with climate denialism, which could yield cuts to public university funding.

Ranking institutions by climate resilience is something we should expect to see, given how many academic ranking systems already exist.

I appreciated your book’s discussion of how each academic discipline could center the climate crisis — from ethnic studies scholars studying the impact of climate change on indigenous populations, to literature scholars analyzing emerging texts across science fiction, climate fiction, and afrofuturism. You also anticipate more inter-disciplinary work that centers climate change, as well as altogether new fields of study.

I’d love to know more about how you see this coming about — how can faculty and students drive these kinds of curricula changes? And, how can faculty and staff help students navigate the trauma of living through this moment?

I think we’ll see new fields and curricula emerge in part in the way they have done historically. Brilliant faculty members can carve out new domains through bold investigation. New fields emerge at the interstices between academic units, as research crosses between formal boundaries. Passionate students, staff, and faculty can call for the creation of new programs, too. Such emergence may be supported by extra-academic entities, too, like foundations, governments, and companies.

That sounds fairly orderly, even rational, and does describe some changes. Yet we need to bear in mind the possibility of campus politics becoming unstable and much more contested at times during the climate emergency. Imagine students in the Greta Thunberg generation discovering that their campus invests in fossil fuel companies, has a petroleum engineering program, goes out of its way to welcome petroleum-spewing vehicles on campus, serves lavish amounts of meat for all meals, sends faculty and staff around the world via jets, and sources its electrical power from coal. They can easily use today’s technologies to organize protests, demonstrations, sit-ins, strikes, and more. Some faculty and staff can join or inspire, even lead them. They can just as easily elicit support and hostility from the outside world.

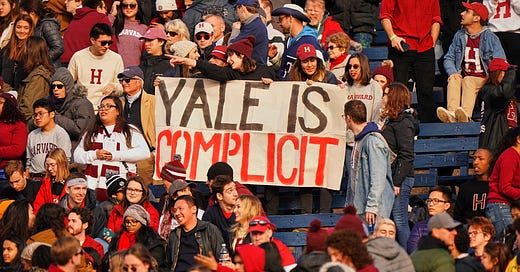

We’ve already seen early signs of such campus political battles, from hard-fought fossil fuel divestment campaigns to protests at athletic events. We should also not discount the possibility of campus climate politics turning to violence against property and/or people, as Andreas Malm has argued and Kim Stanley Robinson envisioned.

I’m fascinated by town-gown dynamics in college towns. The relationships are often fraught for a number of reasons — colleges are often seeking to grow larger, which can anger neighbors. And there are complicated political dynamics.

But, climate change is going to affect all of us, whether or not we live on a college campus. In an ideal world, how would college towns and colleges work together on climate change issues? What are some of the hurdles getting in their way, and how can those be addressed at the municipal level, or even at the state level? And how could anti-science lawmakers impede these efforts?

This is a very important and very complex subject. Ideally, campuses and their local communities will recognize shared experiences, dangers, and opportunities. Academic institutions can use their academic strengths: conducting research on their neighborhoods, connecting students with local internships and service learning, and providing public research. Schools can also provide climate-specific services, such as cooling shelters, sustainability research and teaching, and assistance with climate adaptation measures.

But climate work can flow in both directions. We could see campus activists seeking to mobilize the surrounding community to cut greenhouse gas emissions, shift transportation from driving cars to mass transit, install wind turbines, produce and consume less red meat, and so on. The town can also influence the gown: Imagine a city or county which races ahead in climate work under an energetic leadership team, for example, and the campus is faced with the challenge of catching up.

Of course, there are obstacles to benevolent collaboration. A campus striving to mitigate global warming could run afoul of a local polity embracing climate denial. Economic pressures on either community can restrict their respective thinking about how to cooperate with the other. Gaps between different cultures and ways of being in the world can split collaborative efforts.

And all of this assumes a reasonably stable politics, without climate change causing deeper political tensions. Scholars have already identified a series of ways for global warming to drive challenging political situations: increasing authoritarianism; emergency rule; millions of climate refugees; governments struggling to maintain services; terrorism.

Ultimately, I think a sense of shared fate is perhaps the most powerful way to cross the town-gown barrier.

We often hear about the housing crisis on college campuses — and some of the proposed solutions aren't pretty. What would a college campus of the future look like, if it were to be built with climate change in mind?

It depends on how far a campus wants to go. Does it want to preserve its historical identity, or does it seek to adapt to a transformed world? Will its population decide to participate in climate mitigation efforts?

Electricity plays a role. We can imagine a campus dotted with solar panels, covering roofs, frameworks set up over (and perhaps within) paths and roads, and on freestanding structures. Wind turbines might stand high, their reach exceeded only by a blimp mooring station. A creek would feature a hydro installation. Vehicles would be quiet, most or all being electrically powered, rather than petroleum-burning, and bicycles would be plentiful. Buildings would be covered with green, as plants (both ornamental and for food) appear on windows and roofs. Those buildings might be on stilts, if the grounds are threatened by flooding. There are fewer empty lawns and more gardens.

The interiors of buildings may offer more connections to nature than they currently do. More and bigger windows and doors, perhaps driven in part by the COVID years, let natural sights, sounds, and scents inside. More plants appear. More ambitious designs include larger plants - trees - and water within academic buildings.

For some institutions these will be entirely new locations, as they migrate away from their older sites, now threatened by global warming. The Solarpunk design movement, for example, offers some good ways to think of Anthropocenic campuses.

You end your book acknowledging that none of this work will be easy, but urgent action is needed. And, I came away from your book feeling, if not hopeful, exactly, at least somewhat energized — higher education is such a powerful force in society, and there are many different routes institutions can take. When it comes to how higher education is responding to the climate crisis, what is giving you hope?

Many things give this futurist cause for hope as we foresee academia over the next two generations. The human capacity for invention and innovation encourages me, giving rise to new possibilities for post-carbon society. Every week we see new ideas and projects for everything from new battery technologies to carbon storage mechanisms, plant-based food to ways of avoiding unjust measures, new ways of telling climate stories to understanding how the human psyche might change as the climate transforms. Higher education clearly plays a role in this innovation ferment, from educating and inspiring people to conducting research and development. Academia’s commitment to imagination and empathy is surely a powerful ally to humanity’s vast struggle.

The attitudes towards the climate crisis among younger people gives me hope for what they can accomplish as they rise in power and influence. Polls show younger generations being more informed, more concerned, and more active in the climate realm than their elders. As they arrive on campuses as students — then, as staff and faculty, then as senior leaders — they hold tremendous potential to transform our institutions.

Above all, academia itself gives me hope. Think of it: an institution devoted to preserving and creating learning, and sharing that through teaching, publication, and outreach. Colleges and universities are, among other things, precious nodes for humanity’s intelligence and imagination. Roughly 20,000 colleges and universities exist around the world, a glorious realm of knowledge, exploration, and possibility. Think what we academics could contribute to save the world in this vast crisis!

Universities on Fire is slated for a March 2023 release. Pre-order a copy here and follow Bryan on Twitter here.

About the Interviewer: Colleen Murphy is a policy journalist whose editing and reporting has appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education, CalMatters, and Bloomberg Tax, among others. Starting Tuesday, she’ll be the managing editor of Open Campus, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigating and elevating higher education. You can find her on Twitter here.

If this is a vision of the future of academia, I'm sorry to say that it's extremely troubling.

Stripped of its excess verbiage, Mr. Alexander's call for academic activism precipitates higher education directly into partisan politics. Thus it embodies a demand for the imposition of ideological conformity. One could say, I suppose, that he's merely proposing to formalize the de facto situation. Our institutions of higher learning have travelled a long way down that road already—and we can see that campus activism, whether on climate, race, gender, social justice and economic issues has already narrowed the range of campus thought. Semester by semester, more and more thoughts become unthinkable—thought crimes, as Mr. Orwell called them.

If I understand him correctly, Mr. Alexander's argument is that higher education's core mission is, or should be, to summon the future. It's a mission supposedly justified by the fact that "Colleges and universities are, among other things, precious nodes for humanity’s intelligence and imagination." Well, this may have been true in the past. And in certain areas of inquiry, mostly in the hard sciences, it may remain true today. But in the humanities and the so-called social sciences, radical relativism holds sway—and inevitably, it will come to infect the hard sciences as well. Already we hear claims that mathematics, physics, etc. are artifacts of the "White patriarchy," and that "other ways of knowing" are equally valid. Indeed, the incontrovertible fact that science, as such, is the creation of Western culture and civilization comes under attack from scientists themselves. All this strikes me as the opposite of "intelligence and imagination."

Finally, there's the problem of intellectual vanity, a vice that permeates Mr. Alexander's view of the university's role. Intellectuals, scientists included, have always been prone to this vice, e.g. Bertrand Russell gassing about nuclear disarmament and world peace. Intelligent people who have mastered some branch of knowledge remain fallible human beings. All too often they imagine that their understanding extends to subjects and issues of which they have no more knowledge than many ordinary citizens. A good example is Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, the well-known healthcare expert. How far his expertise really extends is a good question. How much does he really know about hospital administration, medical billing, pharmaceutical research and development, the manufacturing of medical instruments and devices? No, upon examination his knowledge extends over a mere sliver of a complex field, many of whose interconnections neither he nor anybody else understands or perhaps even suspects. Pick any university. Add up the knowlege and expertise of its faculty, administration, support staff and student body. The sum total would not be enough to produce so much as a single bedpan.

To summarize, postmodern progressive ideology is fundamentally opposed to the principle of intellectual freedom that is the one and only justification for the existence of higher education. But that principle is today reviled as a thought crime by the very people charged with its preservation.