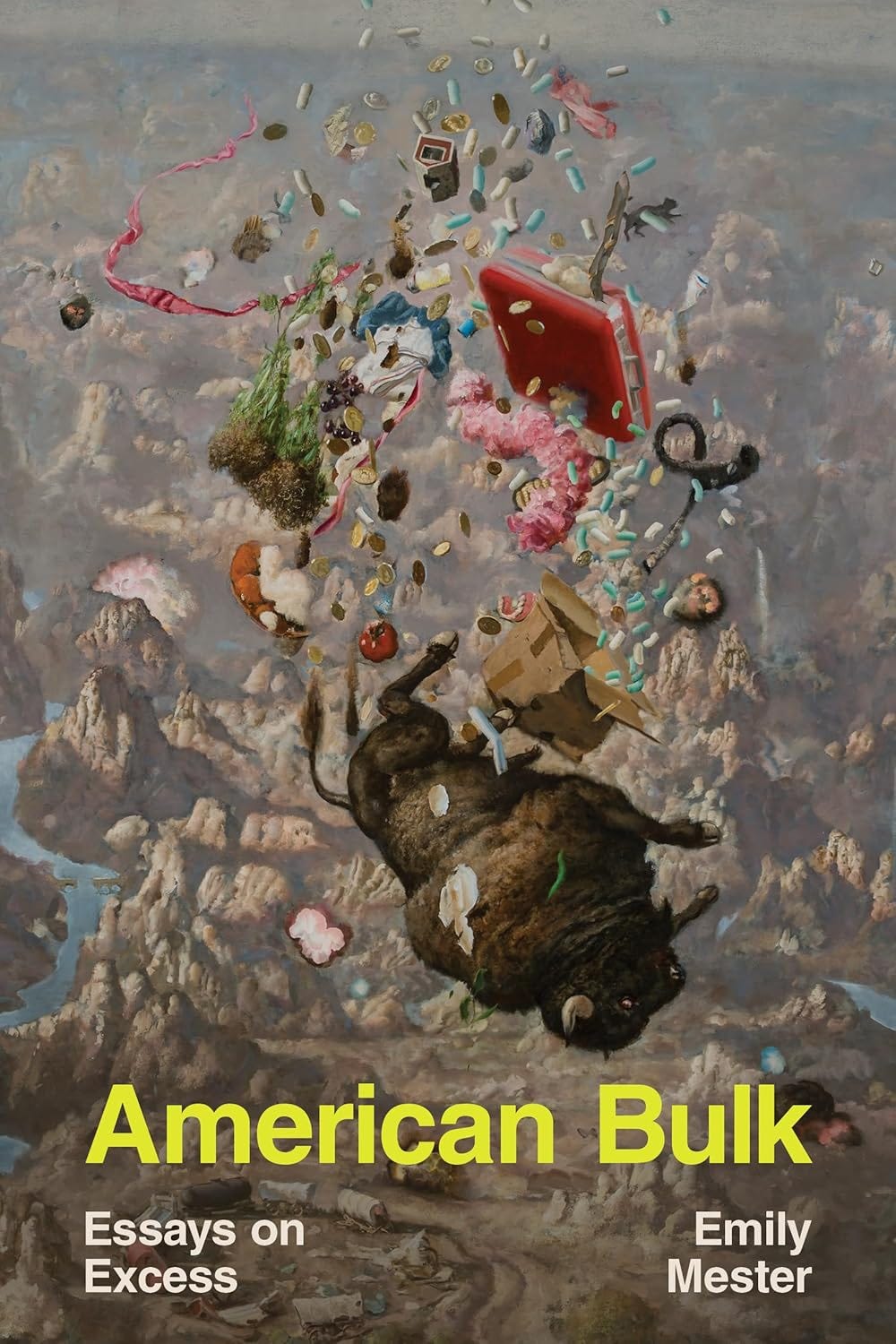

American Bulk

"Bulk is too personal to be written like a scourge, too fraught to be written like a haven. It’s just an American ethos that sits very close to the bone."

This week’s episode of is one of my favs we’ve ever recorded, and not just because it’s about something I love (skiing) and unpacking the culture around it. I’ve spent the last few years coming to terms with how industrial shifts, climate change, conglomeration, the explosion of the unregulated short-term rental market have changed not only who can learn to ski, but who can keep doing it. You can listen to the episode here, and subscribe below so you never miss an episode. And because I know a solid handful of you are working through the “where should I live, if I have the freedom” question — we talk about it extensively at the end of the episode.

I try to use this description sparingly, so it’ll keep its power: this interview is a real just trust me. It’s about Costco, and American hunger for (and dissatisfaction with) abundance, and how we grapple with accumulation and desire across generations, and Emily Mester — author of American Bulk: Essays on Bulk — will hook you immediately. So consider giving this interview some time, and if it strikes you or challenges you, I strongly recommend buying the book. And I’m grateful, as always, for your trust — I try very hard to use it in a way that will engender more. Directing you to this interview is exactly that.

You can buy American Bulk: Essays on Excess here or here.

To give readers a sense of the scope of the book, I’m going to start very simple — how have bulk and excess shaped you, and, in turn, shaped the way you process your self in writing?

I grew up in a family of hoarders and compulsive shoppers. Or actually, no, my four siblings and my mom are zero percent those things. I grew up with precisely one hoarder and one compulsive shopper. My frugal grandma buys almost nothing and hoards valueless objects—brochures, tissues, the little plastic thing in a pizza box. My dad, her son, buys on such an astonishing scale that the things become kind of valueless too.

In the midst of the LA fires, I’ve been thinking of what my grandma or my dad would mourn if their houses burned down. I couldn’t think of much. They’d mourn it as a financial loss, yes, as a logistical nightmare, yes, but for two people who seem markedly attached to stuff, neither of them seems to have much attachment to any particular item. My dad could replace his vast athleisure wardrobe, along with his laptops and cameras and tools and cars, in a matter of weeks. In fact, he might relish the opportunity to go on a sanctioned spending spree. My grandma owns like three pairs of pants, a laptop that acts as her lifeline to the world, and that’s about it. Neither puts much stock in set dressing: art, trinkets, fine furniture, landscaping. They don’t even put much stock in houses.

As I say in the book, it’s a privilege to amass things and houses, but it’s an equal privilege to be able to abandon them. My dad got to a point where he had enough money to sort of flit from house to house when one filled up with stuff or the novelty wore off. My grandma is not rich like that, but when her home in Iowa got too overwhelming, she packed a single suitcase and fled. The house is still there, still packed, sealed like a little tomb. I once asked her how she’d feel if it burned down, and she admitted this is what she wishes for every day.

Family mementos mostly suffer the same fate. They have either been abandoned, or else so overtaken by other objects that they’ll never be found. We have so many far-flung storage garages and dusty crawlspaces overtaken by power tools and DVDs and 15-year-old computers new in the box. What’s a baby blanket to a pile like that? My dad bought dozens of fancy cameras when I was a kid, and took thousands of pictures of us on them, but those photos are mostly stuck on memory cards in a tower of plastic boxes that will eventually be given away, because the memories are attached to an object, and objects, in my family, are everything and nothing. When I began writing the book, I tried to frame my grandma and my dad as opposites in consumption. They certainly think this is the case, and it’s a lot of the reason they don’t speak anymore. But as I tried to draw these distinctions, they collapsed.

And lest my tone read overly judgemental, it’s important to say this: I’m exactly like the two of them. Whatever they’ve got, I inherited it. I have all the same impulses, tempered by more favorable circumstances but still far from normal. I’m my grandma if, at a critical age, she’d had access to psychiatric care and less pressure to find a husband. I’m my dad if, at a critical age, he’d had generational wealth and a Tumblr account. I’ve let garbage pile around me as I lay there practically bedbound. I’ve put on a well-fitting pair of pants and experienced my delight as a need to pull out my phone and buy a second pair right there as I stand before the mirror. If I was gonna put my family on blast, it was important to convey that any judgment or revulsion was coming from a place of deep recognition. Writing this book got me down to the root of our consumption. I’m more empathetic to it than I ever thought I could be. I’m attempting a no buy in 2025, and if I ever needed confirmation that this is, in fact, pathological, the gnawing hole left by not buying is it.

Bulk shares DNA with consumer culture and mass culture, but it is sweatier, denser, fleshier than those things. Bulk culture is Costco, but it is also fat camp, hoarding, haul videos on Youtube, sweepstakes, an Amazon review that accidentally reveals a deep well of anguish. Bulk culture isn’t wealth, or riches—it’s stuff. And though each of our relationships with stuff is rooted in class, the language and practice of wanting is not. The impulse that made my dad amass iPods (RIP) like they’re pennies in a jar is the same impulse that leads others to sneakers, Beanie Babies, makeup, yard sale junk. Our love and pain and dysfunction speaks the language of stuff. But also, IDK, stuff can be fun. Everyone has stuff. Humans are the only animals that engage in commerce, so maybe it’s kind of necessary. When John Lennon asks if you can even imagine no possessions, it’s like, no! I can’t! Lay off me! Can you???

I wanted to write this book because under the surface of the consumer landscape lies this deep (and deeply American) pathos, and nobody was talking about it the way I wanted. I’d read lots of clinical reports, lots of finger-wagging opinion pieces, lots of pitch-black satire, and some wistful apologia about chain restaurants being Good, Actually, but I’d never really read a story of consumerism the way I knew it. To me, bulk is too personal to be written like a scourge, too fraught to be written like a haven. It’s just an American ethos that sits very close to the bone. I wanted to write about stuff the way you would write about your family: tenderly, critically, curiously. Like something you’re a part of, even if you don’t always want to be.

I’ve never read the real appeal of Costco, particularly the appeal to a certain sort of Dad, and a certain type of Dad who likes to go every damn week, described with such precision. You write: “Costco is not for what you need. It’s for what you want.”

But also: “To people like my dad, Costco offers far more than a good deal. It offers the lulling comfort of permanent volume, the same bulwark against scarcity that draws us to the all-you-can-eat, the BOGO, the unlimited refill, the family size. The endless, the bottomless, the lifetime guarantee — these promises are not to be underestimated, because their flipside is terrifying. To want a boundless supply means also to acknowledge a boundless need. We are inclined to hunger.”

You comment on this a bit in the essay, but I’ve thought a lot about how growing up poor and becoming middle class, or upper-middle-class, or just somehow coming to occupy a place of abundance actually expands this hunger, and at some point you realize as much, but don’t know what to do about it, so just…..keep buying more. Clearly I am also writing about my own family experiences here too, but I’d love to hear you talk more about how you see class anxieties and indulgences working here.

The Costco piece is the one that launched the book project. I initially set out to write an essay just about the store, not my family, but the more I dug, the more I found it impossible to untangle the two. Beneath my dad’s love of bulk shopping lay both joy and deep neurosis, in almost equal measure. Moreover, the shopping and the feelings did not simply occur side by side. They fed one another. Buying dozens of tool sets and multipacks of beef jerky made my dad feel safe and abundant, but his obsession with abundance, and the wealth that begets it, also could make him volatile and selfish, because I think, on some level, he wasn’t sure if he deserved it, and was scared he’d lose it all.

I once read a piece about Downton Abbey that compared class in America to a greasy pole: you go up, you go down. Or really, you worry you’ll join the people below you, wonder if you’ll catch up to the people above, but mostly just cling to the pole, sweating just to stay in one place. The question of whether or not you “deserve” your job, your salary, it eats at a lot of people. Whether you have a lot or a little, you either have to see your status as a direct result of your efforts—a reward—or understand it as utterly arbitrary. Or maybe, usually, it’s a bit of both, but you have to parse which is which, merit or luck, and you never will. I think it’s why people at extreme ends of luck sometimes turn to religion, because God is a far more cogent explanation.

Success, to my dad, is a god without grace. There is no accrual of goodwill — if he stops working even for a second, it could all be taken away. And so he works constantly, more than he even has to, more than most of his peers, which in law is saying something. Even now, as he nears retirement, you’d think he’d be able to kick back and enjoy the fruits of his labor, but he doesn’t even take Sundays off. If you pour that much of yourself into something, you have to believe there’s a reason. The hours turn into money, and the money has to turn into something, and so you shop. I guess shopping is his fruit. This transaction makes sense to me.

To me, the most inexplicable rich people are the ones who are really really frugal, like Warren Buffett. It’s no virtue to spend money, but I’m like wait, so you’re not even doing this to ball out? You’re the chairman of a multinational conglomerate holding company for…the love of the game? He’s pledged to donate 99% of it, which is great, but I don’t think philanthropy was his motivator, moreso just an acknowledgment that the money does, in fact, have to go somewhere when you die. Philanthropy is the decorative urn, but what was his life’s raison? I think a lot of people who climb the ranks of class can wonder the same thing.

My grandma has the Buffett mentality. She was a schoolteacher but has accrued a sizable nest egg from never, ever spending money. She hates the food at her assisted living place, and I once encouraged her to treat herself to Panera French onion Soup. She was like No Em, I need to save money. Slow and steady wins the race, and I was like What race? Death?

The essay on your experience at fat camp manages to grapple with external and internalized fatphobia, solidarity and its relationship to fat liberation, the contradiction of weight loss in a loving environment, societal repulsion with fat camp as a concept, the beautiful time-away-from-time that is camp — it’s complicated and exquisite and unlike the majority of body writing I encounter. What did you want to convey, most of all, when writing this essay? What’s the bad faith reading, and what’s the reading you hope for?

I love that last question, and I love that you felt it was approaching body writing in a different way, because that’s exactly what I was trying to do. In the same way that I wanted to write a book about consumption that was not preachy or clinical, but also not overly nostalgic or simplistic, I also wanted to write a piece about fatness that was more complicated and ambivalent. Not a stiff piece about the body, but also not a piece that hugs my body too close to its chest, insisting so much on body positivity or neutrality that there’s no critical distance. In fighting for fat liberation, some writers have (understandably) taken a pretty hard-line approach to food and body image, where you shouldn’t call any food “bad” or admit that, even as you fight for respect in the fat body you have, your first wish from a genie would always be a thinner one. I’m in awe of the work they’ve done, and find it extremely cool and punk to make hard-won peace with your body. These are people who would simply ask the genie for like, a billion dollars and world peace, and I’m in awe of those people.

But that’s not me, and it wasn’t fat camp. The contradictions I felt at fat camp are the same contradictions I’ve felt about fatness in general: the pockets of joy and beauty and acceptance were still framed by the understanding that I still wanted it to go away. In the essay, I say this: Before acceding to the difficult, lifelong task of trying to change our minds, we were seeing, one last time, whether we couldn’t just do the easier thing, and change our bodies instead. In the past few years, I’ve finally succeeded at doing the easier thing—which is the next essay I want to write — and life as a thin person has been interesting, and often bittersweet, because it showed me that I wasn’t wrong, that it’s so much easier to be this.

The first time I heard this honesty, it was Elna Baker’s piece in a (fantastic) This American Life episode. She speaks sensitively and thoughtfully about her life as a fat person, which ended when she lost 110 pounds. Her life as a thin person has been no less fraught, but she admits, also, that it’s much easier. She acknowledges that she probably wouldn’t have her job if she hadn’t lost weight, and even gets her husband to concede that he wouldn’t have dated the old Elna. It’s heartbreaking, and it feels unfair to both of them, because on the one hand, they both know it’s true, and on the other hand, she doesn’t necessarily fault him, because she ceded to the same societal forces. The piece ends with her admitting that she still takes the prescription stimulants that helped her lose the weight. The last line: I know that all of this is wrong. I don't like what I am. But I've accepted it as part of the deal.

Her ambivalence, like mine in the fat camp essay, is never resolved. I’ve been thrilled with the response to the book overall, but if a reader takes issue with something, it’s often this refusal to declare something bad or good, which some people mistake for me not having a point. This book is a memoir that bills itself as critical-but-personal essays, which it is, but the essay heading sometimes makes people think they’re getting something more declarative, or more informational.

I hesitate to call this bad faith — people want different things from nonfiction, and my book is not all of those things — but one reviewer didn’t like that I refused to endorse or condemn fat camp. I was baffled that this was levied as a criticism. Does anyone actually want to read that? A polemic about fat camp writes itself. It’s such low hanging fruit, and it’s far too simplistic. Nor did I feel uncomplicatedly good about the place. I mean, you can only feel so empowered at a place that weighs you every Sunday like a prize pig.

I wanted to talk about what it feels like to be fat in the world, and what it feels like to be fat alone in your bedroom, and what it feels like to be fat with four other fat girls on a lake in July and you’ve cautiously rolled up your shirt a little, lying there in the grass, and you haven’t felt the sun on your belly since you were eight years old. Here: Finding bittersweet moments of self-love and body solidarity in a place meant to rid us of those very bodies: 3.5 stars.

Your grandmother structures this book, both formally (she is at the center of the first, middle, and concluding essays) and as general influence and guide. When we’re introduced to her, it’s through your childhood eyes, in a section that reminded me in the best ways possible of Jo Ann Beard’s The Boys of My Youth.

It also reminds me that grandparents take on such potent roles in our stories of self: we’re somehow able to see them as people, with beguiling histories, in a way that’s not always accessible with our parents. Also: grandparents tell their grandkids things they’d never tell their children; they’re funnier and far more willing to talk shit.

That’s a long way of saying that your grandmother is very alive in these pages, and your rendering of her made me think constantly of my own Midwestern grandparents, with their peccadilloes and accumulation and coarse friendliness, so much of it the result of grappling with continued scarcity during and after The Depression and the war. Even if they were too young to deal with it themselves, they dealt with its constant shadow. I think this is particularly true of the women, whose options for survival were so circumscribed.

You are very good at showing instead of telling, but I wonder how much of her attitudes around accumulation and thrift were a product of the time and place and context of where and how she grew up — and how much of that legacy do you feel in your own family line?

The word “peccadilloes” is so apt that it almost feels onomatopoetic or something. Like yes, whatever my grandma is, it makes a sound like peccadillooo, peccadilloooo.

I often forget my grandma is a product of the Depression because she never references it. You’d think that would be a foundational event in her life, that she would use it to explain her frugality, but she mostly just says that her childhood was comfortable. She lived on a farm in Iowa, her mom raised chickens, her dad tended the rest.

If there’s a dark shadow on her stories, it’s mental health. She’ll reference her mom’s moods, her dad’s dark periods, her suicide-prone ancestors, the monsignor who lost his mind. She talks far more about “my depression,” which takes her through very low periods and high, frenetic ones, and which, I note in the book, she pronounces dee, not duh. She’s remarkably candid about it for someone who didn’t really have access to treatment til late adulthood. The book is as much about mental illness as it is about class, but I sort of didn’t realize it until I reviewed the essays and went Hmm, there seems to be this dark cloud over the essays, even the ones that are supposed to be funny. And then I was like Oh, right…the dispositions.

I think that, as a wife and mother, she both resented the role and had trouble meeting its demands amid all her own inner turmoil. It’s hard to know which came first: did she resent it because she struggled, or did she struggle because she resented it? In the book, I try to square the jolly, warm, everyone’s-favorite-teacher grandma in the Mickey Mouse sweatshirt with the cruel hypocrite my dad seemed to think she was. He told us that she’d say she regretted raising him before she’d even gotten done raising him, would say it right in front of him, which is unimaginably cruel, and I couldn’t picture it. I can now. I think her frugality was, in some sense, an extension of this resentment. The book talks about how she was so punishingly frugal that my dad grew up assuming he was poor, because there was no other explanation for why they refused to buy him a baseball glove or insisted he still do his paper route when it was -10 outside and he was like, eight.

The gulf between tense, inscrutable parent and genial, open-book grandparent is most remarkable when you watch it exist in the same person. My dad recently became a grandparent. I watch him lead my nephew by the hand, walk him over to our blind skittish dog and show him how to gently pet her nose. If my nephew spills his water, there’s no yelling, no explosion of frazzled nerves, just Oops, well that’s ok. It’s really sweet, and kind of healing, if a little bit disorienting. I wonder if he felt the same watching her.

It’s hard to clearly remember your own childhood, and so as the child watching the grandparent transformation, you’re left wondering, Were we ever like this? What changed? Could we still be? In the Storm Lake chapters, a lot of what I tried to do is go back and see what happened, how they got that way. At the time of the book’s writing, they hadn’t spoken to each other in years. Recently, she sent him a simple email that said Happy Birthday. I’m gently pushing for more.

And a final question Emily added for the end:

A question nobody has asked me: how much did you pay out of pocket to license the Warren Zevon song you use as the book’s epigraph, and was it worth it?

$300, yes! ●

You can buy American Bulk: Essays on Excess here or here.

And if you liked that interview - if it made you think, if you send it to friends, if you want to keep the paywall off it and future interviews like it - consider becoming a paid subscriber:

Paid subscribers get access to all the weekly threads (like yesterday’s, which will help you find the next show to watch amidst the streaming abundance), all the weekly recs and links, every Just Trust Me — plus the knowledge that they’re making work like this sustainable. We’re also doing a classic Culture Study Advice Time Thread this Friday, so subscribe now if you want to get in on that early.

I love so much about this interview and want to talk about my grandmother’s obsession with collecting cardboard boxes and wrapping supplies to reuse that I have inherited (who needs a small trunk of already curled curling ribbon???) but first:

This is the perfect opportunity to put my brilliant new store idea out there and hopefully one of you beautiful people will be inspired! You don’t even have to pay me royalties just knowing it exists would make me happy. So I’m thinking, what we need is the opposite of Costco—I like to call it Minico! With two thirds of American households made up of one to two people, there should be a huge market (pun unintentional) for small sizes of things. I am specifically interested in half bags of marshmallows (no one can finish a full bag making s’mores for one child!), 4 oz containers of sour cream, and half bundles of cilantro. Let’s make this happen!!!

This is beautiful, thanks.

I think a fair bit about hoarders because we have an immediate neighbor who is one -- every couple years our condo association forces her to hire a clean-out crew and then within days she's back bringing carts full of stuff into her place. I don't know her well enough to have any guess at what motivates her, but I know it hurts her -- her adult child will occasionally visit but I don't think she'll go inside the apartment. (The one time I've been inside, to help with something my neighbor couldn't reach, the smell alone was powerful reason not to go in.)

At some point I did some errands for a former coworker who was largely homebound and she apologetically said that some apartment inspection had classified her as one of the lower stages of hoarder and I looked around and said something like "I know a serious hoarder. You're just a person who's had a full life that doesn't quite fit into the size of apartment you have now."

That's something I think a lot about -- how the amount of space you have (related directly to the amount of money you have, in most cases) can determine how you're viewed on this front. Of course some people, like the grandfather and father described here, are so extreme that no amount of money could cover it up. But, like, when I met her, my mother-in-law was in an impeccable, beautifully decorated 4,000 square foot home -- and when she went to downsize, it turned out that out of sight of the clean surfaces and lack of clutter, there was So Much Stuff. Every cabinet, every closet was jammed full. She gave us bags of old mail she'd never passed along to my husband, like years of bank statements and wedding invitations, and a stray tax document for one of his cousins who'd used her as an address during college. There was a big basement storage room filled with furniture from her previous 7,000 square foot house -- she didn't have room to use it but hadn't wanted to get rid of it. So she had this massive amount of stuff, but it was invisible. She hired an organizer and took weeks or months paring it down. Which she did, but as long as her space allowed it, her inclination had been to hold onto everything.