This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

If you read any of the hundreds of advice columns that have found renewed life on the internet, you’ll recognize a certain genre of question. It comes from a woman, almost always married, who’s describing a partner’s shitty behavior. They often narrativize the behavior in a way that simultaneously asks the reader to understand that something is wrong (my partner/my family/my coworker is the asshole) while also framing the behavior in a larger framework of excuse (maybe I am the asshole?). Men do occasionally submit to these columns, but I find this genre almost always comes from women — because women have been taught, through various ideological machinations, that if there is something wrong in their lives it is almost certainly their fault, and if it is their fault, they must personally seek ways to fix it.

Earlier this week, Ashley Nicole Black articulated a corner of my fascination with this genre. As she put it, “do women not know being single is an option?” (For the unfamiliar, ‘AITA’ is a Reddit forum where people tell their grievance and ask ‘Am I The Asshole?)

People do realize that being single is an option — but, depending on their background, they are often abjectly terrified of it. Why, in a culture that ostensibly celebrates strong, independent women, does this fear remain? It’s about money and keeping things together for the kids, of course — but it’s also about a lot more than that.

I’ve spent the last week immersed in research about the financial and cultural realities of being unmarried or single. I’ll be expanding on the financial reality at length for the next in my series for Vox , but I’ve been fascinated by the scholarly sub-discipline of “marriage studies,” a mix of largely legal and sociological work on who gets married, when and why they do, and whether they stay that way.

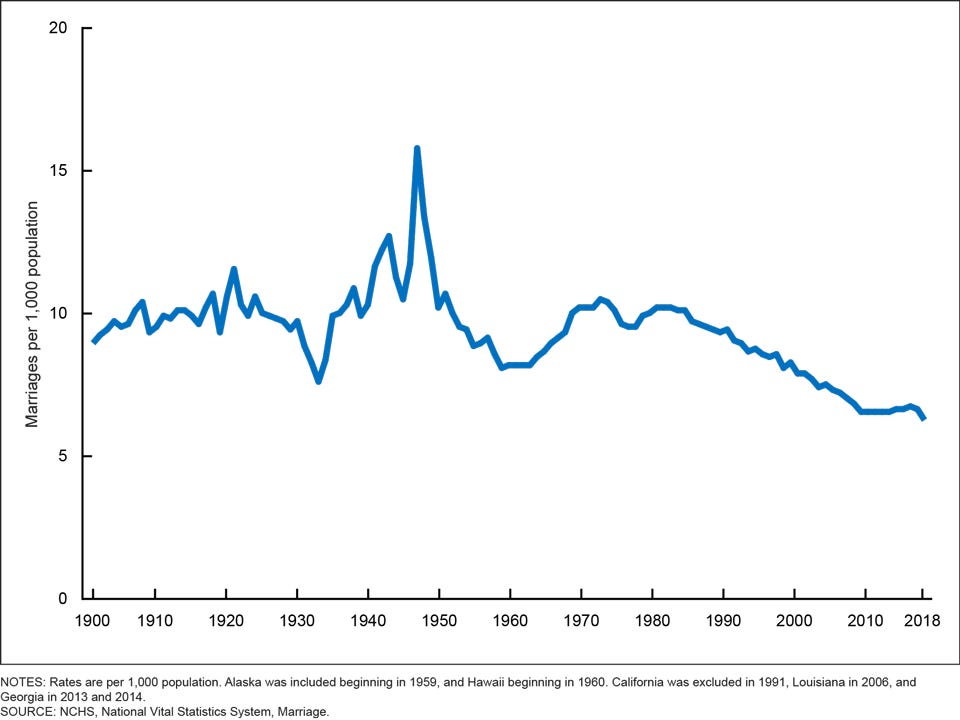

Right now, there’s a popular understanding that marriage — and divorce — rates are declining. This is certainly true in the aggregate. Here’s the nationwide marriage rate chart:

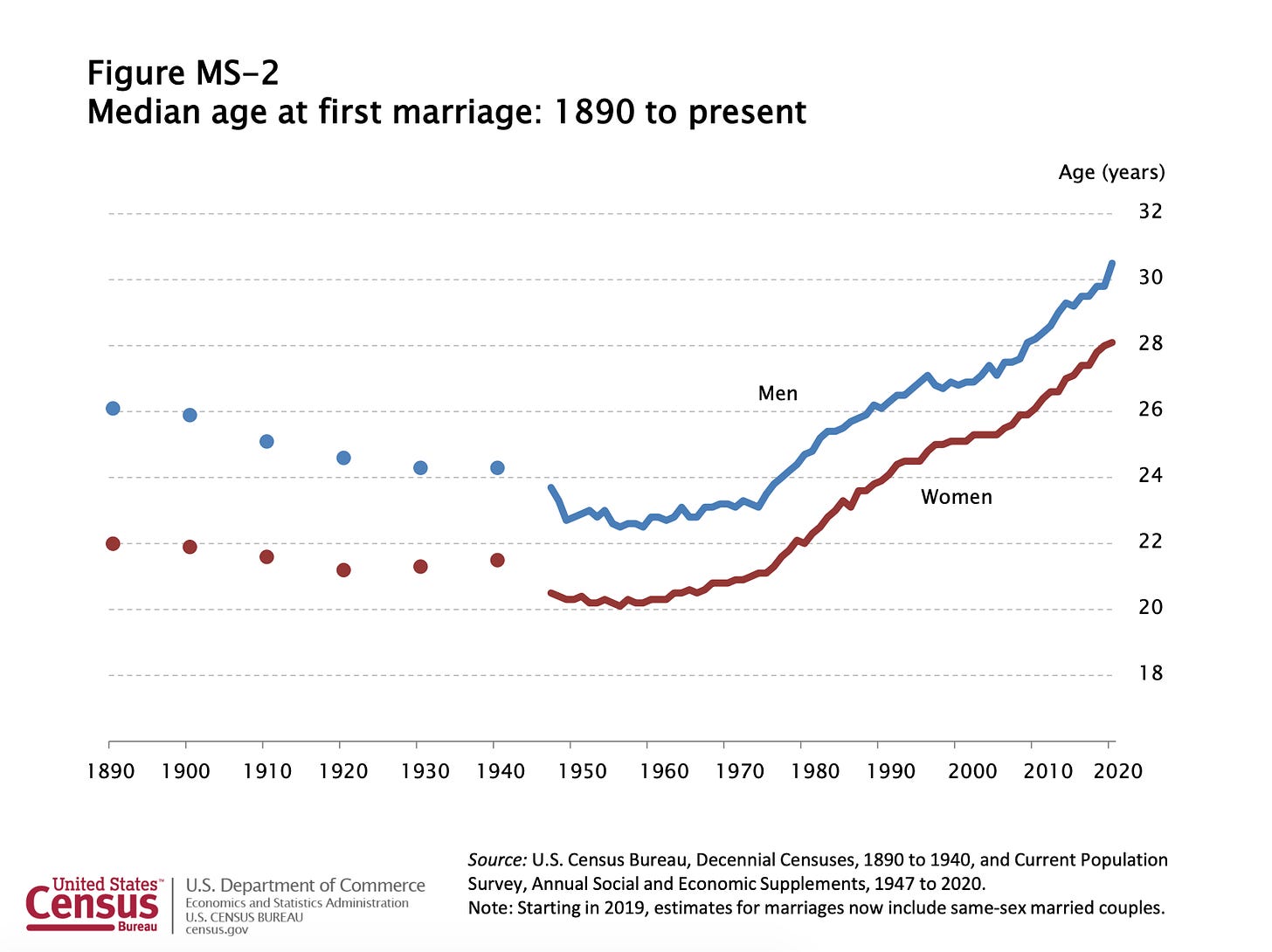

Meanwhile, U.S. divorce rates also hit an all-time low. In 1960, the divorce rate was 9.2%. It peaked in 1980 at 22.6%, and has gradually declined ever since. By 2019, the divorce rate was 14.9%. The median age for marriage has also continued to rise:

People are waiting longer to get married, having fewer kids, and then staying married longer, presumably because they had more time to think through whether or not they wanted the marriage.

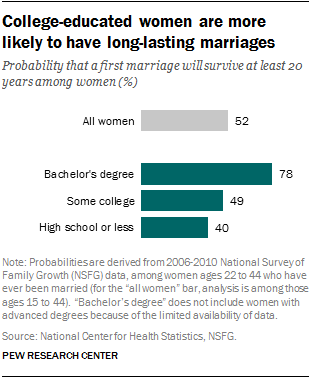

If this sounds true to you, and true of the people who surround you, then chances are high that you’re a middle-class college-educated person who is largely surrounded by other middle-class college-educated people. Because the aggregate trend obscures some much more complicated — and telling — trends in marriage, divorce, and single parenthood. While divorce rates have continued to decline for those with college degrees since no-fault divorce was first introduced, for people without a college degree, divorce rates leveled off and then began rising in the early ‘90s. For women, the chances of your first marriage lasting 20 years goes up significantly the more education you have.

There are also significant differences in marriage outcome depending on race: for Asian women who were married between 2006 and 2010, the probability of their first marriage lasting 20 years was nearly 70%. For Hispanic and White women, the probability was around 50%. For black women: 37%. A reminder, though, that all of this data is intersectional. You can’t look at those numbers and extrapolate that “Black women are less likely to stay married because they are Black.” The more accurate conclusion: systemic and historic racism has made it so that Black women are less likely to go to college, but also less likely to have family wealth that affords a robust financial safety net in case of emergency, or provide a down payment on a house, or cushion the blow of job loss or economic downturn, all of which make marriages more likely to last.

Those financial factors also make it less likely for people to get married in the first place. Census data from the 2015 American Community Survey showed that 26% of poor adults between the ages of 18 and 55 were married — compared with 39% of working class adults and 56% of middle and upper class adults. Sixty percent of poor Americans are single, compared to 50% of the working class and 40% of the upper and middle class. This wasn’t always the case: back in 1960, rates of marriage and divorce were roughly the same amongst the college educated and those without a degree.

But again, the lesson is not that college educated people are wiser and stay married and people without college degrees are somehow less wise and do not stay married. A lot of things were different in 1960s: for start, it was a whole lot harder to get divorced, and women had far less access to credit and capital. But college education was also far less neatly associated with class position. A whole lot of people without college degrees, particularly but not exclusively white people, had access to the stability of the middle class.

You can look at the rise in divorces over the course of the 1960s - 1980s as the result of the growing cultural destigmatization of divorce, and you can look at the increasing age of marriage and childbirth as the result of birth control, legal access to abortion, and increasing numbers of women going to college. But you can also think of both of these shifts as a secondary effect of the gradual destabilization of the portion of the middle class without college degrees.

And here’s where I think it starts to get really interesting. These trends, now decades in the making, have pulled conceptions of marriage and its purpose in two directions. Legal scholars June Carbone and Naomi Cahn argue that the fetishized Leave it To Beaver middle class marriage of the 1950s was the result of 1) the widescale movement of industry, e.g. work, out of the domestic sphere and into an office and/or factory, which resulted in 2) a less hierarchal understanding of marriage, with the woman as ‘queen’ of her domestic domain, entrusted with the care and nurturing of children and the suburban home.

We might look back on these marriages and see them as regressive, but as a whole, they were significantly less utilitarian and more companionate than what had come before. Men and women weren’t necessarily equal, but they were two parts of the whole. This understanding flourished in the post-war period, when the United States’ brief industrial dominance, the G.I. Bill, robust unions, and tax structures and regulation reduced income inequality to its lowest levels in record history. Some of the eagerness to enter marriage was, in truth, an eagerness to enjoy the fruits of the middle class: a home in the suburbs, a washing machine, and, if you were a man, a wife to cook you dinner. At the same time, the lack of contraceptives, legal abortion, or culturally acceptable cohabitation made it so that even if you weren’t inclined towards that dream, if you wanted to have sex, you didn’t have a lot of other choices.

As I’ll talk about at length in my piece for Vox, so many of our safety nets — both public and private, from social security to healthcare — were set up to favor people who configured themselves in this way. Power pooled in these middle-class marriages. But then the sexual revolution, the feminist movement, the decline in strict religious observance, and the rise of no-fault divorce began to reconfigure the middle-class family into something far more dynamic. Divorces led to remarriages, step-siblings, half-siblings, and custody battles. A whole swath of people dropped out of the middle class entirely, many of them newly divorced mothers whose standard of living, according to one 1976 study, fell between 29 to 73 percent. And as Suzanne Kahn explains in Divorce, American Style, building on that statistic, “even many divorced women who had never before identified as feminists turned to the burgeoning women’s movement for an explanation for the situation in which they found themselves and for the tools with which to deal with it.”

I’ve long argued that the children of these sorts of middle-class divorces — children who experienced downward mobility, and watched their mothers, many of whom had been out of the workplace for years, struggle to regain stability in their own lives — absorbed lessons about what marriage can and cannot provide. Getting married does not make you stable. A stable marriage makes you stable. Having enough money makes that stability easier. But it’s certainly not enough. Put differently, the utility of marriage — what it’s good for, what it promises, what it communicates — began to change.

Carbone and Cahn argue those changes have polarized into two understandings of marriage: one “blue,” the other “red.”

The Blue Model:

“Embraces the new middle-class strategy designed to meet the needs of the information age.”

Invests in the earning capacity of women as well as men

Generally includes a delay in marriage and childbearing until financial independence and emotional maturity (aka, waiting until “you’re ready”)

Conceives of sexual activity, in or outside of marriage, as a personal decision; contraception is great, abortion is acceptable

Clustered and most common in urban areas and “secular coastal areas”

Sees the Red Model as intolerant

Conceives of good child-rearing in terms of building supportive environments for kids that will then allow them to avoid what sociologists sometimes call “negative outcomes,” including unintended pregnancy

The Red Model:

Views the advice to wait until you’re financially secure to have children as an offensive suggestion that poor people shouldn’t have children

Common in more religious areas of the country

Sees the Blue Model as evidence of moral and spiritual decline

Believes in abstinence before marriage

Takes an extremely hardline against abortion

Understands the responsibility for childrearing as the provenance of the parents alone, including information about sexual reproduction

You can see the larger ideological consequences of these paradigms: the Blue Model, according to Carbone and Cahn, “places less emphasis on family form (marriage by itself is not the answer) and more on creating an infrastructure (e.g., education, family-friendly jobs, access to contraception and abortion) that encourages the right choices.” The Red Model creates a system “that tries to channel sexuality and childbearing into marriage in an economy that fails to provide a financial basis that can sustain resulting unions.” And so: participants in Blue marriages who theoretically place less value on the institution of marriage have longer lasting marriages, whereas people in Red marriages divorce quicker and at a higher rate.

What’s ironic, of course, is adherence to the Red understanding of marriage is actually eroding the value of marriage within Red adherents — whereas the Blue understanding is, in turn, arguably making marriage seem more desirable within Blue communities. We can also extrapolate further on Carbone and Cahn’s definitions, and understand Blue marriages as far more likely to be feminist and to be nurturing and accepting of different sexual identities. If you’re not religiously or politically conservative, Blue marriage seems like a much better deal. What’s not to like? Blue Marriages almost certainly went to the Women’s March!

But again, it’s more complicated than that.

Carone and Cahn don’t say this explicitly, but Blue Marriage is progressive bourgeois. Some people in Red Marriages — in particular, members of the American Gentry — might make just as much money, but they wield it differently. Blue Marriage expands to include a mode of childrearing (intensive), an ideal of partnership (shared, communicative), and a belief that women’s labor is valuable in or outside the home. It is predicated in a particular mode of consumption, from groceries and holiday cards to kids’ extracurriculars and family vacations. It resists fiscal conservatism but is still likely a little itchy about housing density. It theoretically believes in fostering and funding a community that nurtures all within it, but is, in practice, often too overwhelmed with work and parenting duties to cultivate or participate in it.

Crucially, Blue Marriages are not exclusively white, but there is a crucial proximity to the power associated with the white bourgeois. [I personally don’t think there’s enough space in this conception for first- and second-generation immigration families or for people of color without a lot of financial capital who find white progressive liberalism alienating — if you have thoughts on that, I’d love to hear them in the comments].

At this point, there’s no good data on how marriages fared during the pandemic. Right now, any reports of skyrocketing divorce filings are still muddled by long-term Covid shutdowns and pauses. But I do think the pandemic has clarified some people’s understandings of their Blue marriages, even if they haven’t ended them. The microscope that was long-term partial quarantine made many realize that maybe your marriage isn’t the sort of marriage you thought it was. Maybe your partner, having now seen all the invisible labor you do around the house, still isn’t offering to figure out a way to divide it. Maybe you have really different understandings of risk and safety. Maybe your partner doesn’t actually think your job is valuable. Maybe it’s very clear that they’re not going to ever go to therapy for issues that are too big to talk through on your own. Maybe, like the husband in the letter to Slate’s Advice Column, they are emotionally and verbally hostile to your children. Maybe all of the childcare responsibilities still fall on you, even though we’re both working from home. Maybe the ideals of a Blue Marriage are a fairy tale that you kept telling yourself about the state of your relationship. And maybe that terrifies you.

Because as normalized as divorce has become within society as a whole, it has been denormalized for people in Blue marriages. It is a different stigma than when it was frowned upon for religious or moral reasons, but it is a stigma nonetheless. Within this larger polarized conception of marriage, divorce has become something that people unlike you do; like being unable to conceive, it is an identity-smasher. And for people who considered their route to marriage and/or parenthood to be well-reasoned — and, depending on your family history, the opposite of what others in your life did — it can feel like a real failure, of foresight and wisdom and perseverance, for it to fall apart.

The letters in advice columns often overflow with an unsettling mix of propriety, descriptiveness, and desperation, all attempting to underline all the ways in which a marriage is, in fact, a good (Blue) one….save this one small thing. The problem is that one small thing too often belies a larger brokenness: one partner is wholly unwilling to communicate, or to raise children in a way that both of you agree is safe or nurturing, or to set boundaries against toxic relatives. Or, even sadder, it’s clear that the author’s spouse doesn’t actually respect them at all — not their labor, not their mind, not their interests, not their fears — and they’ve been reconciling themselves to a partnership that isn’t actually one.

This situation is complicated by the fact that bourgeois women have been taught that everything, whether the pay gap or enduring domestic labor discrepancies, can be fixed through hard work: hard communication work, hard organizational work, hard therapy work. If they just put in the hours — in their relationships, on top of the hours put into their jobs and their parenting and their body maintenance — everything would work out. The dream of having it all, for so many bourgeois white women, is still tantalizingly within reach. Others know it was never open to them in the first place.

But even a privileged white woman can’t burnout their way to relationship stability. Sometimes there is just no antidote to dick.

Still, apart from loss of identity, there are a lot of reasons that divorce can feel abjectly terrifying. We are a nation still oriented around those puddles of married, middle-class power that accumulated in the post-war period. For heterosexual couples, the gender pay gap is still very real, and in queer marriages, there’s similar long-term earning penalties if one spouse stayed home long-term to care for kids. Affordable housing is harder than ever to come by. Unless you can pay for a good attorney and live in the right state, the legal system is generally shit when it comes to alimony. If you don’t have a full-time job, how will you find good health care, especially if you have a chronic condition?

And then there’s the resignation: dating sucks. What if, well, all men suck? What if there’s nothing better. What if you’re throwing away family and social and financial security just so, what, you can not feel like a devalued piece of shit every day? Not worth it! Power through it! Sunken cost! No matter how much feminist theory you’ve read, no matter how much you’ve celebrated others in your life who’ve chosen a single life, there is also a wrenching, paralyzing fear of being alone. The utter abiding and degrading shit that I have seen women endure in order to avoid that fate — it disarms me. It terrifies me, really. That, as a culture, we’ve effectively arranged the dynamics of un-marriage to resemble a horror movie: a fate to be avoided at all costs, no matter the injury we endure within the marriage.

A lot of this, as Barbara Ehrenreich would put it, is about fear of falling (out of one’s ‘earned’ class) and the lengths people will go to prevent it. But I also think a lot of it, particularly with ‘Blue’ marriage maintenance, is about proximity to bourgeois whiteness. It’s notable that Ashley Nicole Black, a Black woman, was the one who pointed out that so many of these letter-writers don’t seem to view being single as as option. For decades, Black women in the United States weren’t permitted the rights or privileges of marriage. They were forced to come up with other ways of making single life survivable. Black women are also familiar with the experience of having your marriage status pathologized — and having systemic, societal failures diagnosed as personal, moral ones. They understand that part of the reason bourgeois white ladies are so afraid of being single, even if they might not ever be able to articulate it, is fear of being treated the way our society treats Black single women.

Lyz Lenz, who writes the excellent newsletter Men Yell At Me and is working on the forthcoming book This American Ex-Wife, described this fear intersecting with the fear of losing implicit and explicit investments in patriarchy. “Right now, patriarchy benefits white women,” she told me. “They are personally invested in the money that come with being a white married couple. They benefit from this — through status, through stability, and through money. And in order to get divorced, you have to lose social status and you lose money. Even if you later gain more income, that is not a guarantee.”

What’s more, there is a prevailing understanding — even within ostensibly progressive Blue marriage circles — that divorce will compromise up the very hard work you’ve done to make sure that your own kid is headed towards their own placement in the American hierarchy. If a child struggles in some way, the blame will not be directed on larger systems that make it incredibly difficult to find stability for single parents. It will be on the mother who chose to blow up her family’s lives.

That sort of shame, that fucked up understanding of who’s failed and who they’ve failed, that unmooring realization that your identity and stability is yoked to someone who devalues you every day? It is so much to sit with. As one person very kindly put it in the comments to my query about why women hesitate to leave these marriages, “I feel for anyone who is reading these responses and feeling ashamed and sad and alone.”

But unless we collectively begin to understanding divorce and living as a single person in this world as not just survivable, but authentically generative — that fear will continue to discipline so many women into staying in situations that offer them financial stability and social standing but otherwise degrade them. And those decisions, as desperate and personal as they seem, simultaneously prop up existing hierarchies — particularly when it comes to patriarchy, heteronormativity, and power.

It is a failing of white bourgeois feminism that its adherents have failed to agitate in ways that are un-ignorable for significant changes that make single life — including single life as a mother — possible. Which is why it’s not enough, not nearly, for bourgeois feminists to embrace a Blue understanding of marriage and the privileges it affords. As Britney Cooper writes in the foreword to Kyla Shuller’s The Trouble with White Women: A Counterhistory of Feminism, “it’s not that white women can’t do good in the world or be useful allies in feminist world-making. The problems, rather, is white feminism and its gravely limited conception of how to address the injustices that all women face.”

Feminist liberation will only arrive when we have the genuine freedom to not just have the option to be alone, and/or without children, but for that option to be stable, and to feel complete, and, as feminists have long promised, and as I personally believe, for that path to be understood as what it is: glorious. ●

For more on the ways that could and should happen in a financial sense — that’ll be in the Vox piece, which, along with an interview with Kyla Schuller on The Trouble With White Women, will arrive in your inbox in the weeks to come.

Correction: the original edition of this newsletter included a quote that asserted white women as more likely to be stay-at-home moms. Hispanic mothers are most likely to have that role.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. That’s where you’ll find the weekly “Things I Read and Loved,” including “Just Trust Me.”

Other Subscriber Perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus channels for Job Searching, Advice, Chaos Parenting, Spinsters, Climate Grief, Today in Celebrity, Productivity Culture, and so much more. You’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I'm not even done with the piece yet, but this paragraph, holy fuck:

"This situation is complicated by the fact that bourgeois women have been taught that everything, whether the pay gap or enduring domestic labor discrepancies, can be fixed through hard work: hard communication work, hard organizational work, hard therapy work. If they just put in the hours — in their relationships, on top of the hours put into their jobs and their parenting and their body maintenance — everything would work out. The dream of having it all, for so many bourgeois white women, is still tantalizingly within reach. Others know it was never open to them in the first place."

I'm going to have to sit with that for awhile. My marriage, while far from perfect, is solid, and has actually gotten better during quarantine (it helps that my husband has made dinner every single evening of our marriage - other then going out or take out - that REALLY helps, plus he is an excellent co-parent). But where this hits home is the fact that while I KNOW my academic career is dead, and I know and exactly WHY it's dead (because of my academic training), and I TELL myself (and others) that my academic career is dead, I can't quite stop believing that if I just work harder and smarter and keep working the problem, that it will somehow, magically, not be dead. It's fucking pathological.

Thank you very much for this great piece! I think women (all of us) subconsciously understand that the kind of "strong independent women" that society purportedly celebrates is the women who carry an enormous burden silently and make it look absolutely effortless, and the moment it stops looking effortless we know it suddenly becomes a terrible inconvenience to everyone around them and erodes the way others perceive them. So if you have ever experienced anything like that in your life (and many women probably have), it really dictates (or destroys) the vim and vigor you're able to muster for striking out on your own.