This is the weekend edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

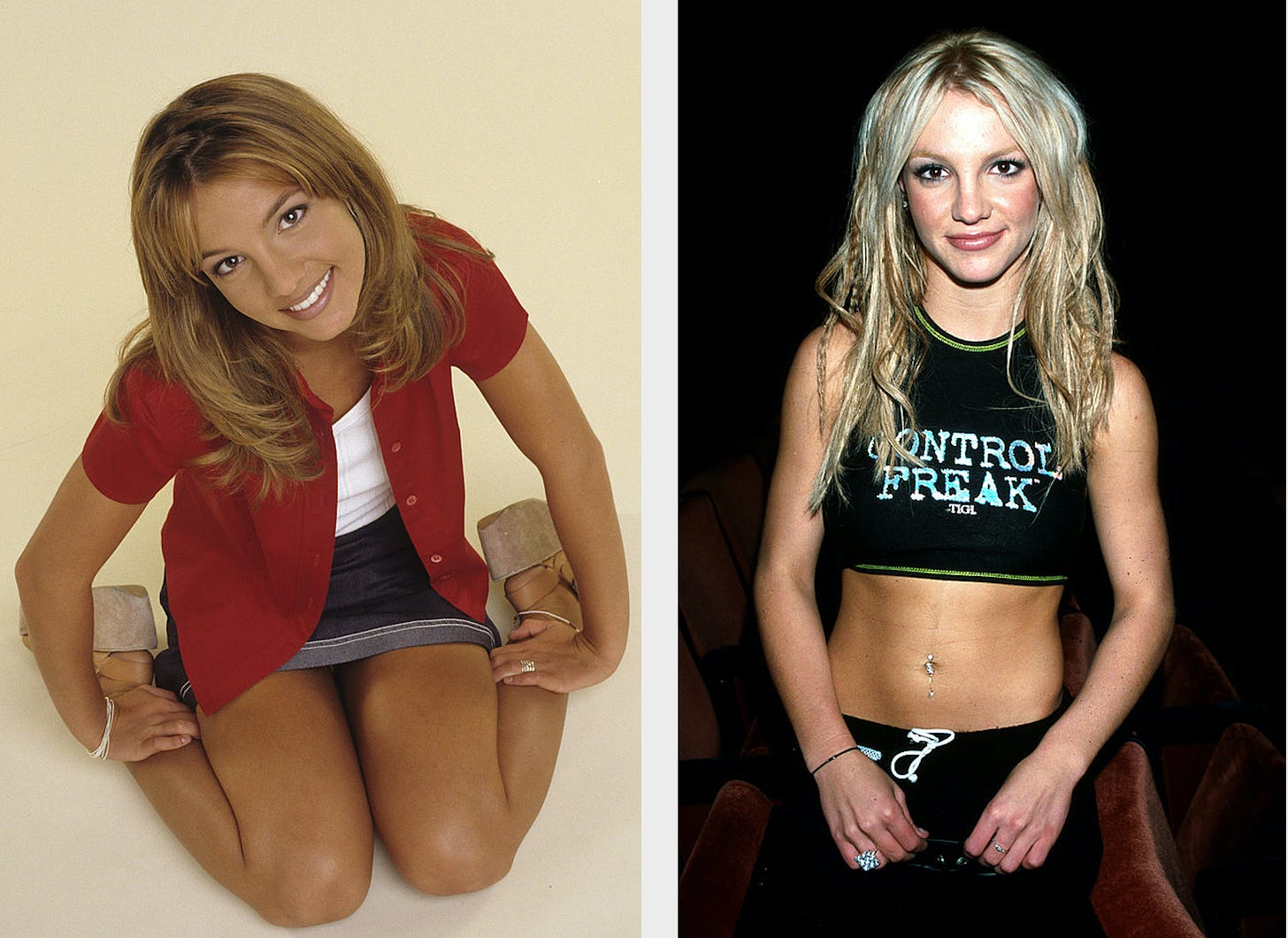

How does a millennial begin to tell the story — her story — of Britney? The first time I saw, really saw, that image on the left, a friend and I had were at a guy’s house after school, just to, I dunno, have some snacks? I don’t know if kids do this anymore, but it was a defining part of my high school: let’s go pick up slurpees at ZipTrip and just be in each other’s proximity.

In this guy’s basement, next to one of those little nerf basketball hoops, was a tacked up poster of that image, probably around 12 x 16. Britney was different because she wasn’t. She wasn’t a super model, she didn’t represent some unattainable beauty, she didn’t look like the women in the Victoria’s Secret catalog or writhing in the sand in the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition — all of which, to that point, had served as my barometer of female beauty. She just looked like she could just be the hottest girl in my small town Idaho high school, and that poster was just one of her senior photos. She probably went to the tanning salon downtown, the one that didn’t make you get permission from your parents, and paid my hairdresser, Pam, $19 plus a $4 tip.

What Britney had seemed attainable, which is what made the power she held over so many of us potent. This is the problem of the girl next door. She tortures you. I don’t blame Britney for this. But her midriff — and the fashion trends that followed it — were probably the root source of my disordered eating over the course of the late ‘90s and early 2000s.

But this isn’t a piece about body image, at least not exactly. It’s about the difficulty of making a Britney documentary that will satisfy a group of viewers who grew up and into adulthood alongside her. That was my immediate reaction after watching Framing Britney Spears, the New York Times-produced documentary currently airing on FX and Hulu: 74 minutes is not even close to enough time to tell this story. If Michael Jordan got ten hours, Britney should get ten hours.

Just to be clear: Framing Britney is part of a larger doc series for FX; its resources are not unlimited, and a ten hour series is not within its mandate. Twenty years ago we’d call it a television doc, not a filmic one: more like a Behind the Music, which I used to devour on VH1, than, I dunno, Herzog. But that sort of distinction has become increasingly meaningless in the era of streaming. Something like OJ: Made in America, one of the best documentaries I’ve ever seen, debuted at Sundance, but the vast majority of it audience watched it episodically on television, which is also where most people encounter documentaries of any length today.

Streaming has erased some pretty meaningless taste policing, but it’s also inadvertently encouraged us to ask everything from every media product. Within this new reality, standardized show lengths, narrative pacing for commercials, and season lengths have all come to seem arbitrary. The last season of Game of Thrones was essentially a collection of slightly shortened movies, with budgets to match. Everything should be an eight episode series (or more!) because everything can be an eight episode series (or more!).

When a media product is released to streaming, then, the immediate reception is often why isn’t it [this other format, doing this other thing]? Why isn’t it longer, why isn’t it broader, why aren’t the productive values higher, why isn’t it exactly like the books, why doesn’t it take this fan theory into account, why isn’t it a movie, why isn’t a series, why isn’t it a podcast, why isn’t it everything?

It feels like executives have begun to internalize this criticism, knowingly or unknowingly — which then trickles down to the notes they give on pitches, on scripts, on rough cuts: what if it was more everything? Alternately, that mandate is simply making its way into pitches, and scripts, and rough cuts: this is a niche story about [insert historical figure], but it’s also everything.

You can see how that might have happened in the case of Framing Britney Spears: it feels like a deep-dive into the #FreeBritney movement was expanded into more of an all-encompassing Britney Spears documentary. The end result is an okay #FreeBritney documentary and a pretty limited Britney documentary. It covers the timeline of her breakdown and conservatorship in an effective way, but only briefly discusses the larger issues at play when it comes to disability rights, mental health competencies, and the myriad ways conservatorship has been abused.

But if you dedicated significant time to the nuances of conservatorship, it wouldn’t be a Britney doc, per se. It’d be a conservatorship doc with Britney Spears as its animating example. Personally, I think that would be a very good documentary, but it would be a much harder sell. So what you get instead is a solid televisual representation of a 2500 word New York Times article: a lede, a chunk of backstory to introduce the news peg (aka, the reason we’re telling this story now), some quotes from experts, and a question at the end of what’s going to happen in the future. It serves its purpose. I’m not mad at it. If you’d only spent a few hours of your life thinking about Britney Spears, I think it would probably be pretty gripping and infuriating.

But it’s not the Britney Spears documentary I crave or need. It doesn’t feel like it’s answering the overarching question of why Britney Spears matters, especially for those of us who grew up in the cultural milieu that created her and that she, in turn, helped create. Like Jordan, or OJ, or any truly iconic and enduring celebrity, Britney’s image was used to reconcile so many impossibility contradictory ideologies. There was the classic virgin/whore dichotomy, but with the postfeminist twist of ostensibly “owning” her sexual choices (and thus exercising, as the documentary briefly points out, “control”). She was the canary in the coal mine for digital paparazzi culture — and, along with Amy Winehouse and Lindsay Lohan, was collateral damage as the gossip industry as a whole went through a massive power-shifting convulsion.

And then there’s her embodiment of whiteness and Southernness and class; everything that was going on with purity culture and white Evangelicalism; the catastrophe of postfeminist politics; her positioning as the next Madonna, including conversations about her lack of talent; the cohort of similarly designed singers who came up alongside her (Christina, Jessica, Mandy) and their varying trajectories; the spectacle of her body as a site of control and monstrous abjection; the beginning stages of celebrity pregnancy fetishization in the mid-2000s; understandings of agency (or lack thereof) when it comes to the child stars of the last century; the intersection of demure femininity, “niceness,” and the standards for female behavior in interviews at that time — and that’s just her image, we haven’t even started on what was going on with her music, or her choreography, or her voice, spoken or sung, plus all the dynamics of the conservatorship. All of that, all of that is why she matters.

Like so many others, I find myself fiercely protective of Britney: I want her to find happiness, whatever that might look like, just as I want everyone who came of age during the mindfuck of that period to find happiness. Learning to let go of an ideology’s hold on you — about what you should prize and hate about yourself, about what feels good and bad, right and wrong, powerful and weak — is ongoing, oftentimes traumatic work. It’s not just jettisoning disordered eating habits as high waisted jeans replace low-slung ones; it’s completely reconceptualizing your societal value.

This tweet came across my feed as I writing, and it reminded me of how much time I have directed at self-control and constraint — all in the effort of shaping myself into something closer to the supposedly attainable ideal on that high school boy’s wall. I think of the horror with which we watched Britney navigate the postfeminist dystopia of the mid-2000s, and the internalized lesson that this is what happens when you let yourself go. I think of all the mourning women do for their selves that could’ve been — and how much more intense that feeling of loss must be when it’s not just ideals of femininity you’ve spent years chasing, but ideals of whiteness and straightness and able-bodied-ness as well.

My ideal Britney doc, it would account for all of that. It would be angry and unflinching, but also attempt to understand the building blocks of her charisma. It would remind us of what made her feel so powerful, and the precarity of its construction. It would feel like a reckoning. It might be longer than ten hours. Perhaps it’s impossible. But I know a whole lot of people, largely but not exclusively born between the years 1980 and 1990, who would watch every moment of it.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, which are thus far still one of the good places on the internet.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

Things I Read and Loved This Week:

Every day this feels more and more true to me: Trump will fade like Palin

The art of reverse-engineering knitting patterns from pop culture

A very good piece from Elamin on men and contemporary eating disorders

I know nothing about coding but some of the best and most provocative anti-productivity culture writing has been coming from that sphere

How Amazon transformed the geography of wealth and power

Our bureaucratic systems — HR in particular! — are not ready for the wave of post-COVID grief

One of the smartest things I’ve read on the utility of offices moving forward

This week’s just trust me

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I really appreciated and enjoyed this piece but speaking as a Black woman, I want to flag that the shoehorning in of an intersectional perspective at the end was a little odd and unnecessary. This experience of seeing Britney's teenage image as something attainable with a little more work is I think fundamentally a white perspective. And that's okay! I still appreciate the analysis! But " how much more intense that feeling of loss must be when it’s not just ideals of femininity you’ve spent years chasing, but ideals of whiteness and straightness and able-bodied-ness as well" doesn't quite encompass the difference in experience.

I'm probably about ten years younger than you so Baby One More Time came out when I was in elementary school, but by the time I was in high school I had a best friend who had a similar "girl next door" look to Britney that all the guys in my class were obsessed with. I know what it's like to compare yourself to that standard, but it's really a completely different experience when it is literally not attainable, even if you do 1000 situps a day as the woman elsewhere in this thread did, because you are Black.

It's also worth recognizing that Black girls have different reference points available. The Writing's On the Wall by Destiny's Child literally came out about a month after Baby One More Time. We had TLC. In a few years, we would get Ciara. We saw the midriffs too, but whiteness didn't have to be a part of the equation when it came to ideals of attractiveness as portrayed by pop stars. And of course, as you know, Black girl/women artists never get the madonna/whore treatment. Black female sexuality is instantly perceived as mature in the same way all Black children are perceived as older than they are; never afforded innocence. In fact, the way that most white pop artists signal their maturity is by infusing more and more Black cultural reference points and musical styles into their performances (Miley is an obvious example; and then there's Ariana Grande whose entire popularity rides on racial ambiguity even though she is white).

Anyway all this is just to say, if you don't have space in your argument to really tease out these differences, it's okay to just own the whiteness of your analysis. But it feels a little hollow to throw minorities a bone at the end.

"But her midriff — and the fashion trends that followed it — were probably the root source of my disordered eating over the course of the late ‘90s and early 2000s" - I'm so glad you mentioned this, because I relate. I was 11-12 when Baby One More Time hit TRL. I remember reading in a magazine that Britney did 1,000 situps a day. So I started doing 1,000 situps a day. It's also the same time period where I gained 10-15 more pounds than many of my thinner peers (whose stomach looked a bit more like Britney's than mine) and then spent 2~ decades disliking my body for those 10-15 pounds. I'm not saying any of this was Britney's fault at all. But gosh, I look back at the "cultural icons" of my youth - first Pam Anderson, then Britney and Christina... and yeah, it explains A LOT of how I've internalized femininity.