Where do our politics come from? How we were raised, sure, and how we were educated, but there’s also a sense that how you vote depends on who you are. As in: your race, your gender, and your sexuality. Secondary characteristics (your religion, your class, where you live, what you do for a living) are also predictive, but what they predict has changed with time: white suburban college-educated middle-class women used to be much more likely to vote Republican, for example, and now they’re much more likely to vote for Democrats.

Today, Republicans win by depending on their base: white men. White men invested in the existing social hierarchy, and the assurance that even if they’re not currently on the top rung of the class ladder, their path there remains clear. (People who aren’t white and aren’t male who vote for Republicans are equally invested in that hierarchy — either because they benefit from their proximity to power [white women] or because they, as individuals, want the same place of privilege as white men. They don’t want to destroy or flatten the hierarchy; they want to dominate it themselves).

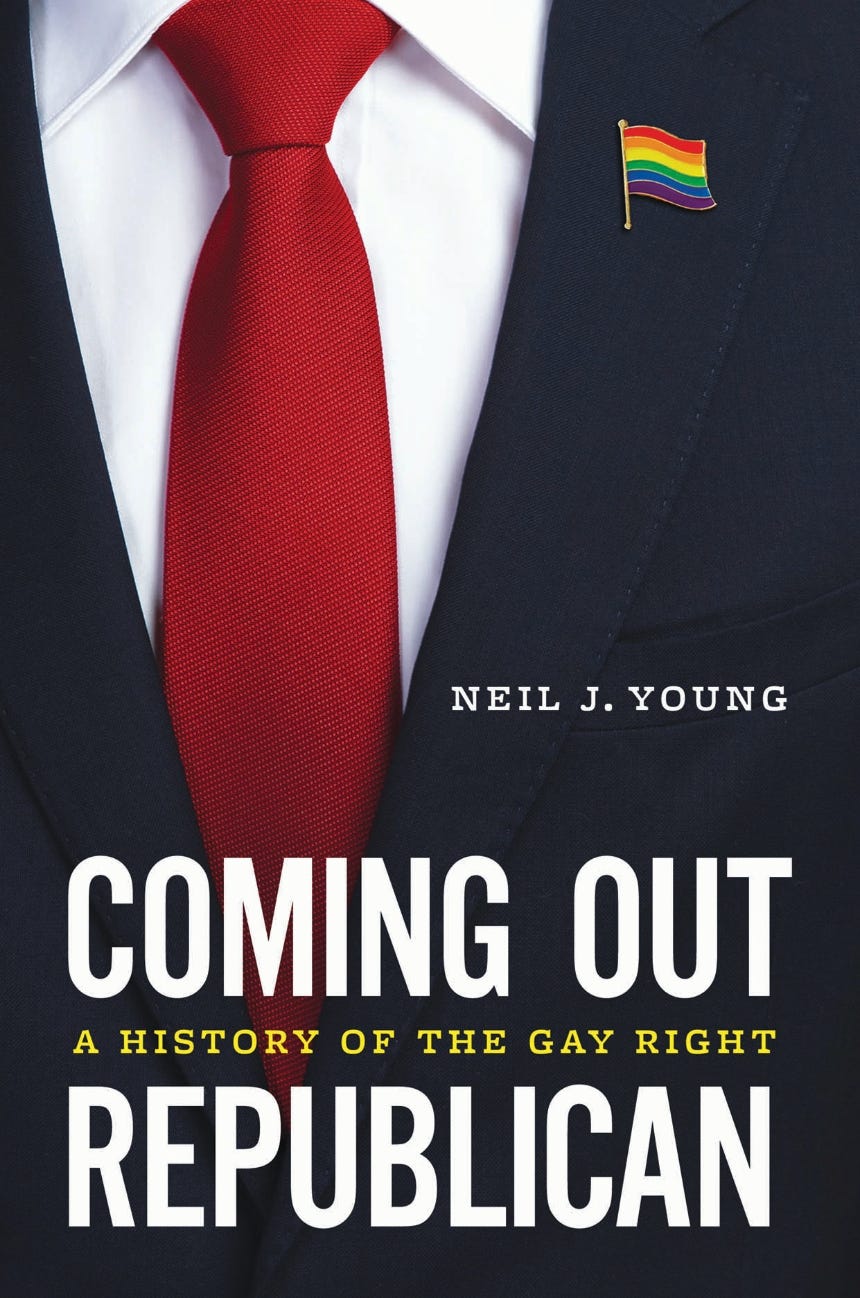

Which helps us begin to understand the existence of Gay Republicans: a group, as you’ll see below, that’s almost entirely white, male, and cis-gendered, and deeply invested in shoring up that sort of power…..even if it requires supporting a party that’s also invested in marginalizing, criminalizing, and even eradicating queerness. It’s a mind-boggling contradiction — but it also has a long political history, one that Neil J. Young has meticulously documented and synthesized in his new book, Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right. I think you’ll find his answers to my questions about the heart of the book, and what we can learn from all this history, as compelling as I do.

You can find more about Neil’s work here — and you can buy Coming Out Republican here.

Your book required you to spend a LOT of time in the archives and do a lot of knotty discourse analysis — but before we get to all of that, I want to zoom out. What made you, personally, want to write this book in this moment?

I’ve actually had this book topic in mind for over twenty years. But two events in 2019 prompted me to move it from the back burner and do it now. The first was, perhaps surprisingly, Pete Buttigieg’s run for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. Obviously, Buttigieg isn’t a gay Republican. However, as a centrist Democrat — at least, that’s how he positioned himself initially during that campaign — Buttigieg was getting hammered from the left, especially from the LGBTQ activist community. That really struck me for a couple of reasons, especially how much that the criticisms of him seemed more focused on his style and presentation than on his policies. But it also made me realize how much we need histories of LGBTQ peoples and communities that don’t tell a progressive story and aren’t about liberal politics.

The second event of 2019 that motivated this book was the outreach both the Trump re-election team and the Republican National Committee made to LGBTQ voters. The Trump team’s efforts built on certain things he had done in the 2016 campaign that marked him as a different Republican presidential candidate, including waving a Pride flag at a Denver rally and being the GOP’s first presidential nominee to ever say “LGBT” in a nomination speech. The RNC’s decision to create a position of senior advisor on LGBTQ outreach, on the other hand, had never been done before.

Now, I view these efforts very cynically, as my writing about them in the book makes clear. At the same time, these were historically significant developments that made me want to dig into the history of gay Republicans and grapple with the part that the LGBTQ Right played in the rise of Trump and broader shifts within the Republican Party.

As much as I thought this was an important book to do, little did I know how urgent it would become over the course of my writing. Up until recently, even progressives, I think, have tended to assume LGBTQ rights — especially same-sex marriage — were fairly secure. And there’s even been this generally accepted idea that, unlike abortion, LGBTQ rights are protected by solid public support, so conservative activists would be unlikely to go after them.

But I think people are beginning to recognize that abortion and LGBTQ rights aren’t separate matters for the Right, but a set of interlocking issues that mobilize the base. And also, that public attitudes about LGBTQ matters can shift. As we all now well know, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill has had a chilling effect on the LGBTQ rights movement and has reignited an increasingly vocal and aggressive anti-LGBTQ activism on the right. There’s good reason to anticipate conservatives pushing further ahead on an anti-LGBTQ agenda should there be a second Trump administration. Even if Trump doesn’t win, these efforts will absolutely continue at the state level.

Largely unknown is that LGBTQ conservatives have aided and abetted some of this, in ways that are both hard to understand and also, frankly, exasperating. And, as I explore through the book, their involvement in this recent rash of anti-LGBTQ activism both fits within and complicates their historic relationship to the Republican Party. Gay Republicanism as an organized, grassroots movement was born when gay Republicans in California came together to stop an anti-gay ballot proposition in 1978 put forward by a Republican state legislator, and one of their main focuses over the decades has been to try to stop social conservatives from gaining more power within the GOP.

Yet at the same time, gay Republicans regularly have supported religious liberty legislation and opposed hate crimes laws, to name just a couple of examples, that many feel serve to undermine LGBTQ freedom. And they have a long history of much more narrowly defining “gay rights” than the broader LGBTQ community typically understood them. Their current delineation of “gay rights” from “LGBTQ rights” — or, even more so, saying they support trans rights but oppose the “radical gender ideology” that the Left is forcing on the nation and its children — continues the unique way gay conservatives have positioned themselves and their politics within the American Right.

The thing that immediately strikes me when I think about Gay Republicans is shoring up societal power and privilege — which a conservative ethos allows a Gay Republican to do, so long as they’re a certain type of Gay Republican. As in: largely white, male, cis-gendered, and homonormative. Can you talk a bit about who we’re talking about when we’re talking about Gay Republicans, both in terms of demographics and their particular brands of conservative politics?

This is almost entirely a story about white, gay men. An early reader of my manuscript asked: “Where are the lesbians? Where are the people of color?” And let me tell you, I tried hard to diversify my central actors here to make sure I wasn’t thoughtlessly putting forward a story about one white gay man after another. But at the end of the day, the historical evidence speaks for itself. Especially for the history I am telling here about the grassroots gay Republican clubs that ultimately formed the national Log Cabin Republicans organization and of the gay right-of-center activists, writers, and politicians who shaped the larger political landscape of gay Republicanism, there were only a handful of lesbians and persons of color involved.

Of course, this overwhelming evidence caused me to sharpen my argument about how gay Republicans often used their whiteness, their maleness, and their homonormativity to stake their place within the GOP — and also how their whiteness and maleness shaped their politics and their political activism on a range of issues, including abortion, affirmative action, immigration, gun control, and welfare.

The abortion issue was especially fascinating to dig into because the handful of lesbian Republicans involved in the gay Republican clubs in the early years kept arguing that in order to attract more women, the Log Cabin chapters and national organization needed to take a pro-choice stance. They contended that supporting reproductive freedom was consistent with gay Republicans’ belief in personal autonomy, privacy, and limited government. They were like, “when we say the government should stay out of our wallets and out of our bedrooms, this is what that means!”

And even though a slight majority of Log Cabin members consistently called themselves pro-choice, a larger percentage didn’t want the organization to take a public position because they thought that abortion wasn’t a “gay issue” and that endorsing the right to choose would harm their making inroads with the party.

That really sums it up, right? Especially when you consider the many things gay Republicans did take stances on and devote their energies to, including lowering taxes, cutting business regulations, increasing military spending, toughening sentencing laws, and restricting immigration — their pronouncement that abortion could be ignored because it wasn’t a matter of “gay rights” has to be seen, I think, as reflective of a fairly patriarchal mindset within gay Republicanism and also the understanding these white, gay men had about how they could best fit within the larger Republican Party.

I do want to say, though, that a history of LGBTQ Republican voters might paint a different picture than what my book does with its focus on the organizations and public figures of gay Republicanism. About 15 percent of LGBTQ voters are registered Republicans, compared to 50 percent affiliated with the Democratic Party. That leaves 35 percent not belonging to either party. In national elections, LGBTQ Americans consistently give one-quarter to one-third of their votes to Republican candidates – and often as many as 50 percent vote Republican in local and state elections. A lot of LGBTQ people are regularly supporting the GOP’s politicians and policies at the ballot box.

But we don’t have polling that helps us break down the category of “LGBTQ voters” into the many subcategories we know make up this broad and diverse community. I think it is safe to say, though, that if we did, we’d have a picture of gay Republicanism — or, I should say, of LGBTQ Republicanism — that isn’t as white, male, and gay as my book’s subjects are. I do hope that in the near future we’ll get much more precise polling of LGBTQ voters. (Think of the specificity pollsters apply to the multiple subcategories of “religious voters,” for instance).

But until then, I also believe it is important to understand that it is gay white men who have disproportionately dominated the institutions, networks, and intellectual and political foundations of LGBTQ conservatism, and who have helped build the modern Republican Party that so many LGBTQ persons often back.

The chapters on early closeted and not-so-closeted Gay Republican leaders and advisors of the 1950s-1970s created such a useful foundation for understanding the conflicting ideologies of contemporary Gay Republicans — there’s the uneasy attempts to reconcile religious mores and sexual desires, the libertarian demand for privacy and freedom from surveillance (unless you’re a leftist!), the frustration with Leftist queer politics….what do those tensions tell us about the state of Gay Republicanism today amidst significant identity-based polarization?

By starting in the era of the 1950s Cold War closet, I was able to put a whole set of different actors making very different choices into play. You have these guys, mostly in Washington, D.C., who are hiding their sexuality because the government’s “Lavender Scare” hunt of homosexuals would have meant their lives would have been ruined personally and professionally had they been found out. Even as the Lavender Scare subsides and homosexuals have more ability to live their lives free of surveillance and harassment, they still tend to disguise their sexuality — some of them even marry women — in order to get ahead in conservative politics. Many of these also use socially conservative positions (including supporting anti-gay policies) as one of the ways they try not to be detected as homosexuals, a strategy we continue to see to this day.

At the same time, you have this other set of guys, mostly out in California, who are able to be more open about their sexuality and develop a more integrated public identity as homosexuals. They have a more consistent libertarian politics — at least when it comes to their own lives. They want a constrained government that doesn’t have the power to come after their private lives or interfere with their businesses: low taxes, little regulation, and no surveillance and criminalization of homosexual activity.

Yet as the federal government and state and local authorities begin to end their coordinated harassment of homosexuals’ lives in the 1970s, gay Republicans start to shift some of their views about the role of the government, especially police power. Now that law enforcement isn’t going after them, they began to support things like robust police budgets, harsher sentencing laws, and “tough-on-crime” politicians.

It’s one of the ways I think we see a fairly consistent habit that gay Republicans have of not only abandoning their critiques of the misuse of government power when it is no longer directed at them but to actually advocating for that use of government power towards others, including Black and Brown persons, immigrants, Muslims, and women, as a way of showing their belonging within the larger conservative community.

One of the ongoing debates among gay Republicans has been a question that also serves as the title of one of my chapters: “Are you a gay Republican or a Republican gay?” That question gets to the conflicting ideologies and identities of gay Republicans – and their interrelatedness. Those who called themselves “gay Republicans” meant that they wanted to show the Republican Party that gays and lesbians belonged to it and, through making themselves visible, encourage the GOP to adopt more pro-gay positions — or, at least to curtail its anti-gay agenda.

Those who described themselves as “a Republican gay" or, more frequently, as “a Republican who just happens to be gay,” saw their mission as building a Republican Party where sexuality wasn’t an issue, although they weren’t very clear about how exactly that would be accomplished. They tended to have a far more limited view of “gay rights,” one focused on ending government discrimination of homosexuals in employment and housing rather than on advocating for the extension of rights, including for some of them even saying they didn’t believe the federal government should legalize same-sex marriage. But generally, these folks were especially uncomfortable with assertions of a sexual identity that they saw as “liberal” and “political” even as they named their own political affiliation as preeminent. And, of course, an assertion of political affiliation is a declaration of identity, especially as this particular one — Republican — is encoded with notions of whiteness, maleness, and even Christianness that the Right views as normative and non-identitarian.

All of this helps us understand, I think, the multiple options available to LGBTQ conservatives in our era of identity-based polarization and how those choices facilitate their inclusion within the American Right. In addition to the long tradition of downplaying or even dismissing sexual identity in favor of other identities — American, conservative, Christian — one of the things that has happened more recently is a spirited assertion of being gay or lesbian rather than LGBTQ or queer.

(It should be noted that the Log Cabin Republicans website does say that it is an organization for “LGBT Republicans.” I asked why the “Q” had been left off, but never received a response. You see this delineation happening a lot in rightwing media where gay and lesbian conservatives argue that “LGBTQ” is a political identity of the Left. On social media, it is particularly rampant. If you want to go down a pretty grim rabbit hole, click on #gaynotqueer or #LGBwithouttheTQ on Twitter or TikTok.)

It's fascinating to watch conservative media embrace and promote this articulation of gay and lesbian identity. On one hand, it reinforces ideas about conservative individualism as contrasted to the Left’s conformity and groupthink. I’m a gay individual, not an LGBTQ lemming. Even more, it positions “gay” and “lesbian” as “not trans,” and helps bifurcate gay rights from LGBTQ rights which many view as only concerned with transgender rights and gender identity now.

That’s a smart strategy to reach a broader American public that continues to show discomfort with a lot of the trans rights movement, especially anything involving underage minors. And it’s worth recognizing that there are a lot of gay and lesbian persons who aren’t conservative or Republican who nevertheless have struggled with the prominence of trans issues or feel like the LGBTQ rights movement no longer represents them – that’s a conversation that is happening in all sorts of LGBTQ spaces. Still, I think all of them would reject how gay Republicans have exploited this to advance their standing within the Republican Party.

What archival find, interview, or conversation most challenged or textured your thinking during the process of writing the book (and doing press for it!)

Oh goodness, it is hard to choose just one! Every good research project provides lots of unexpected moments, but perhaps the biggest pleasure of writing this book was how many surprises it gave me along the way. Maybe I’ll just tease potential readers by saying there are a lot of things in this book that have never been previously reported, and I am especially grateful to the people who shared with me stories they had never told anyone else before, including Andrew Sullivan’s fascinating account of how he came to write his landmark 1989 piece for The New Republic titled “Here Comes the Groom: A (Conservative) Case for Gay Marriage,” an enormously consequential document in the history of the long path towards marriage equality.

But when it comes to an archival find that really challenged and textured my thinking, it has to be a series of documents I found in the collection of the Concerned Republicans for Individual Rights (CRIR) housed at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. CRIR was founded in 1977 which makes it the nation’s oldest LGBTQ Republican organization today, although not the first. (CRIR now goes by the name Log Cabin Republicans of San Francisco.) In the 1980s, as the HIV/AIDS crisis took hold in San Francisco, CRIR underwent an enormously fascinating transformation that made me grapple with and rethink some of the broader historical themes I was developing.

For instance, I knew going into this project that the HIV/AIDS epidemic had profoundly shaped how gay Republicans and conservatives developed their intellectual and philosophical arguments regarding same-sex marriage, especially their contention that legalizing gay marriage was a smart public health measure that would help curtail homosexual “promiscuity” and increase public safety. I just sort of assumed this was an obvious response from a gay demographic that tended to have more religious and socially conservative folks than the larger LGBTQ community did.

But when I dove into the research and started looking at the early years of the first gay Republican clubs, including CRIR, and especially the guys who founded and were active in them, I was pretty surprised by what I found. Those original guys were wild! The San Francisco club had a huge portion of its members that were very active in the city’s S&M and leather scene, and the San Diego organization was started by a drag queen former sex worker. The Los Angeles group held many of its first meetings in the backroom of a leather bar. And there was definitely a sense that these meetings had as much social purposes as they did political ones, a good place for like-minded folks to flirt and organize.

So, given these origins, I was a bit at a loss to explain how we got from there to the buttoned-up, almost puritanical gay Republicanism we see in the 1990s and 2000s. Was it just simply an overactive response to the devastating consequences of the disease?

Instead, as these documents showed, it was a much more complicated process, one where gay Republicans’ libertarian politics – and often libertine personal philosophy – struggled to respond to the health crisis and gradually shifted into a unique form of gay social conservatism. The documents that brought this alive concerned CRIR’s role in opposing the shutdown of gay bathhouses and sex clubs by San Francisco public health officials. CRIR’s opposition aligned them with much of the city’s gay community, including most of the gay Democratic organizations. However, CRIR’s arguments reflected their libertarian politics as they contended that gay men should be free to take their own personal risks when it came to their bodies and that the government shouldn’t interfere in private enterprise. It also allowed them to make partisan criticisms of the Democratic politicians who were behind the bathhouse shutdowns, just more proof in their minds of how the Democratic Party didn’t care about its gay and lesbian supporters.

They won this fight in San Francisco when a judge ordered the bathhouses to be reopened. Yet almost as soon as they secured this victory, they began to wrestle with what they were seeing. Both the escalating numbers of dead from HIV/AIDS and also how the Far Right was using fears of the epidemic to stir up vicious homophobia in the American public and advance an anti-gay political agenda. Gay Republicans adjusted, downplaying their libertarian arguments about sexual freedom and redefining “personal responsibility” which they had once meant as the right for gay men to decide what they wanted to do with their bodies without government interference to now meaning the obligation every gay individual had to not contract and transmit the disease by abstaining from or limiting their sexual activity. And gay Republicans now began to accuse the gay Left of endangering the nation in its reckless defense of “sexual freedom” and its disinterest in pursuing marriage rights. Soon, gay Republicans started promoting what I call a “gay ‘family values’ politics” that emphasized sexual monogamy, gender conformity, and the need for legal same-sex marriage.

Watching all this take shape over just a couple of years in the 1980s was fascinating, but it also helped me appreciate how gay Republicans held onto and remade their political vision as they navigated these terrible events, a process that was far more complicated than the simple “backlash thesis” I had originally thought. And tracing this history in the midst of COVID made all of it take on a deeper resonance for me. The LGBTQ Right has shown a myriad of views about lockdowns, masking requirements, and vaccines, but some of the loudest voices of COVID denialism have come from LGBTQ Trumpers who are prominent on social media. Seeing this current phenomenon through the history of gay Republicans and HIV/AIDS helped me appreciate how a particular politics regarding bodily freedom, scientific authority, and government mandates developed on the LGBTQ Right distinct from but also influential on the broader conservative movement, even as it did nothing to lessen my sense of the dangers that such views hold for all of us as they are mainstreamed.

You write that “when gay Republicans say, as they often have, that it was ‘harder to come out as Republican than as gay,’ they are heightening all Republicans’ sense of victimhood.” The first time I read the book, I underlined that passage four times. Can you talk about how that idea becomes central to Gay Republican identity and also facilitates their inclusion within the party?

First of all, the fact that Anne Helen Petersen gave a quadruple underline to something I wrote will carry me for years to come. Bless you. But yes, this rhetoric was one of the most fascinating things for me to explore as it was such a jarring thing to encounter the first couple of times that I came across it. On one hand, such words fit neatly in the generally hyperbolic discourse of today’s rightwing media, where they are repeated frequently. They seem of a piece with the outlandish and outrageous statements that Trump has normalized within American conservatism, especially its mediasphere.

So, I was especially surprised to discover there’s a longer history here, with gay Republicans starting to say this as early as the 1980s. That perplexed me at first. How could any gay person imagine something – especially, declaring one’s political affiliation – as more difficult than the experience of coming out at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis and amid the virulent homophobia the epidemic reinvigorated? But what I soon realized was that this same rhetorical expression has been directed at different audiences in different times with varying intended effects.

In the 1980s and 1990s, this comment circulated mostly within gay and lesbian media, places like the magazine The Advocate. It was a way for gay Republicans then to scold the gay rights movement which they felt was ostracizing them for their political views and betraying their supposed adherence to liberal values like tolerance and inclusion.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, gay Republicans began voicing this line to the mainstream national media outlets that were giving them lots of attention, places like the Washington Post, New York Times, and even GQ magazine. These publications tended to fawn over the “normalness” of the gay Republicans they wrote about, by which they meant their straight-acting, gender-conforming, conservative-dressing presentation. (Almost all of those profiled, it should be noted, were white men.) At the same time, all of these articles had an underlying befuddlement to them. Essentially, why would any gay person belong to the Republican Party? Now, that’s not a bad question. In fact, it’s one of my book’s central interrogations. But gay Republicans in these years learned that saying it had been harder for them to come out as Republican than as gay was one of the ways they got that sympathetic and even admiring coverage in the first place. Their narrative presented them as both brave but also doubly-burdened. Not only did they have to come out as gay, they also had to come out as Republican! And it redirected the focus away from a homophobic political party they were valiantly trying to make better towards a hostile LGBTQ community that would ostracize and excommunicate some of its own members just because of how they voted.

Especially in the last decade, this rhetoric has happened most frequently and passionately within a conservative mediascape that has a surprisingly large number of prominent LGBTQ conservative figures. The language has a threefold purpose. First, it serves to declare the LGBTQ rights movement – or really, the gay rights movement – as completed, having accomplished what it set out to do. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell no longer exists. Same-sex marriage is legal. And it is no longer difficult to come out of the closet. Therefore, gay rights have been secured, and anything more that is being called for is simply another sign that the “woke,” leftist LGBTQ rights movement will never be satisfied.

Secondly, and more importantly, this language serves to support and enhance the Right’s politics of grievance and its sense of victimhood by presenting Republicans – and, implicit in that, white, heterosexual Christians – as the most aggrieved identity in American life today. Having LGBTQ conservatives vouch for this – at the 2016 Republican National Convention, Caitlyn Jenner told an audience of supporters, “It was easy to come out as trans. It was harder to come out as a Republican,” so it isn’t just gay white men saying this — is powerful. It mobilizes the Right’s version of identity politics that rejects minority groups as deserving special recognition or accommodation while portraying conservatives as the most marginalized and persecuted demographic today.

Lastly, LGBTQ conservatives have asserted their inclusion in the Republican Party and broader conservative movement through this very language. This discourse demonstrates their belonging. We, like you, are harassed and targeted because of our political beliefs, while our sexual orientation is no longer a public matter that needs “special” protection. And our sexuality is secondary, or even incidental, to our political identity which is paramount. It’s a variation of that Mike Pence line, “I’m a Christian, a conservative, and a Republican, in that order.” Gay Republicans are saying they are, “Conservative, Republican, and gay, in that order.” Or, as one popular gay Fox News talking head once said, “I’m a Christian, a patriotic American, and a free-market, shrink-the-government conservative — who also happens to be gay.”

This is a big one, so please take it in whatever direction feels right to you (or feel free to skip if it’s just too much). You end the book by looking at the current state of anti-trans and anti-“woke” legislation — and the very tenuous assumption, on the part of so many Gay Republicans, that the persecution of trans people and criminalization of trans bodies has no bearing on them, even when they are also trans (see: Caitlyn Jenner). As a gay man and a gay historian, how do you think others should process this moment of unprecedented but incredibly fraught freedom?

This was probably the most challenging part to write for a number of reasons. First, these developments are taking place so quickly, and as a historian it always feels a bit awkward to write about something you are in the midst of. I want a good twenty years of distance to really make sense of something! And as you know, when you write a book you wrap things up about a year before the thing actually comes out. It made me nervous to write about the anti-trans efforts because I knew so much would happen between submitting my manuscript and the book showing up in people’s hands. Unfortunately, what has followed has only further substantiated the arguments I make.

Perhaps more importantly, as a historian I also believe that nothing is secure. That history is not a story of inevitable progress. Instead, everything is contingent, and backlashes and regressions are guaranteed, often with even more brutal and devastating consequences than what came before. So, as much as I strove through most of the book for a tone of scholarly objectivity — to the extent that such a thing even exists — I felt like I had to sound the alarm bells in the book’s conclusion because I am a historian who thinks we are quite possibly turning a very dire corner.

I found this especially frustrating in interviewing today’s gay Republicans, including the current president of Log Cabin Republicans. All of them were almost entirely focused on the great freedoms LGBTQ persons have gained as a security for the future. They pointed to laws and Supreme Court decisions as the proof of this. This was maddening to me! Nothing is written in stone; laws can be struck down; Supreme Court decisions overturned. Dobbs, anyone? But they wouldn’t budge on holding onto a view of history that felt, frankly, un-conservative to me in its blind trust in human progress.

I know I’m not alone in worrying that the recent slate of anti-trans efforts is the opening wedge in a broader, coordinated assault against LGBTQ rights, including same-sex marriage. Yet the gay Republicans I interviewed believe that will not and cannot happen. They insist that these are specific and discrete pieces of legislation, not part of a larger anti-LGBTQ policy agenda. When I asked about Ron DeSantis’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, Log Cabin’s president promised that this was only meant for children in the K-3rd grades, and what normal person would want a second grader having to hear about sex in a public classroom?

After the Florida legislature expanded that legislation through the twelfth grade, as I knew would happen, and as it has served as a blueprint for other states across the nation, I reached out to him for further comment, but he never got back to me.

To its credit, Log Cabin has spoken out against some of these recent developments and have seemed to sour on DeSantis. But I suppose my plea to the rest of us is that we not be as naïve about what is happening here. I certainly hope that Log Cabin Republicans will return to its long tradition of serving as a thorn in the side of the Republican Party, by calling out anti-LGBTQ efforts, pressuring Republican legislators to defeat anti-LGBTQ legislation, and backing progressive Republican candidates and policies. But for the time being, the organization – and the bigger LGBTQ conservative movement – continues to participate in the Republican Party’s collapse into full-blown Trumpism.

Log Cabin is unlikely to extricate itself from this entanglement, although a second Trump administration may force them to reckon with their choices. For the rest of us, we shouldn’t have to get to that point to be vigilant, especially when it may be too late. The Far Right that owns the Republican Party has plainly announced their plans for the future. We would do well to take them at their word. ●

You can find more about Neil’s work here — and you can buy Coming Out Republican here.

I'm queer and I live in the deep south in a closed primary state. I have to register as a Republican so I can actually vote in local elections. I don't identify as a Democrat or a Republican. Almost every local candidate runs as Republican which means if you're not registered as one - you're not allowed to vote. Even if a different party runs - a Republican candidate will win. And a lot of the time - the other party is someone who was paid to run by a Republican candidate so the race would be closed from the General Election. Very illegal but somehow they keep getting away with it. For a lot of people in my area, in or out of the umbrella, - we're registered as Republicans so we can have a say locally, not because we're actually Republicans.

I'm going to sail pretty close to the being a butt on the internet line -- and folks should feel free to call me out if they think I've gone over -- but the reason it's hard to come out as Republican in the modern era is that you have to embrace a bunch of embarrassing positions: 'Despite 5 decades of experience, I believe that trickle-down will work this time' 'I've done my own research and have concluded that the overwhelming scientific consensus about climate change is not just wrong about some specific details, but is both completely wrong, and a sham' 'I've decided to live in a fool's paradise and believe that the interpretative framework used in Dodds to overrule Roe could never be applied to overturn Lawrence or Obergefel, and I'm going to trust in the good faith of justices who solemnly testified that Roe was settled law in their confirmation hearings' 'We should pretend that 'don't say gay' bills only bar the discussion of actual sexual conduct, and don't at all impinge on acknowledging varying family structures among teaches and students' 'Donald Trump won the 2020 election, and there's a vast conspiracy suppressing the evidence that this is so' And so many more.

I mean, there's always room to debate appropriate marginal income tax rates, whether incentive structures in certain social programs have perverse effects, and the like, but imo in the modern era, declaring oneself a Republican means that one is giving up the idea of discussing these issues in good faith, based on facts, and adopting a purely ideological yet factually unsustainable position.