If you value this work, and this platform, and these perspectives, and find yourself opening this newsletter every week — please consider becoming a paid subscribing member. Your contributions make this work sustainable.

The first time I understood the power of country music, it was listening to Tim McGraw’s weepie hit, “Don’t Take the Girl,” come out of the tiny speakers of one of the coolest girls in eighth grade’s discman. A group of three or four girls were gathered around, singing every verse, declaring it was just the saddest thing ever. (Yes, this song is very, very sad, but like most country songs, it ends with a bit of redemption). The second time I really understood the power of country music, I was getting a ride on my first day of high school, a gaggle of five girls packed in a rattly red Jetta on a perfect late August morning, with Faith Hill’s “Take Me As I Am” blasting. I felt…confident? As a 15 year old? What a marvel, the ability for a song to make me feel that way.

And the third time I understood the power of country music, I was at a Toby Keith concert at the Yakima Dome in central Washington state in the late Spring of 2003. At that point, I’d loved Keith’s rich voice for years — the maudlin gruffness of “That’s my house and that’s my car / That’s my dog in my backyard ….There’s my kids and there’s my life / Who’s that man / runnin’ my life” — and had ignored his more recent earnest patriotism and jingoism (“Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue.”)

My friends and I thought a concert in Yakima, just a few hours from our college town of Walla Walla, sounded fun — that it wouldn’t be all that different from when we saw Kenny Chesney at The Gorge the summer before. But that — that was a different crowd than the one that showed up in Yakima to eagerly boo every time the Jumbro-tron showed a picture of the (then Dixie) Chicks getting a “boot in their ass.” We were the only ones in our vicinity who didn’t boo, and we were the only ones who didn’t cheer for the visuals of other Toby Keith foes (a man in a turban, most vividly) also getting a boot in their asses, because it was, as the Keith lyric put it, “the American way.”

We didn’t realize we were witnessing a seminal season in country music — as the Chicks, whose lead singer, Natalie Maines, had quipped that she was ashamed that George Bush was from Texas, were unceremoniously excised from country music. The genre as a whole, protected and prodded by an old school publicity machine, began to limit not just the type of women they’d allow into the industry, but the number of women they’d play in a single hour of radio. Fifteen years after that night in Yakima, I remember making the three hour drive from Missoula, Montana to Great Falls — and returning later that afternoon. The connection to my phone was acting wonky, and I ended up listening to three country stations for the entirety of those six hours. I could count the number of women I heard on one hand.

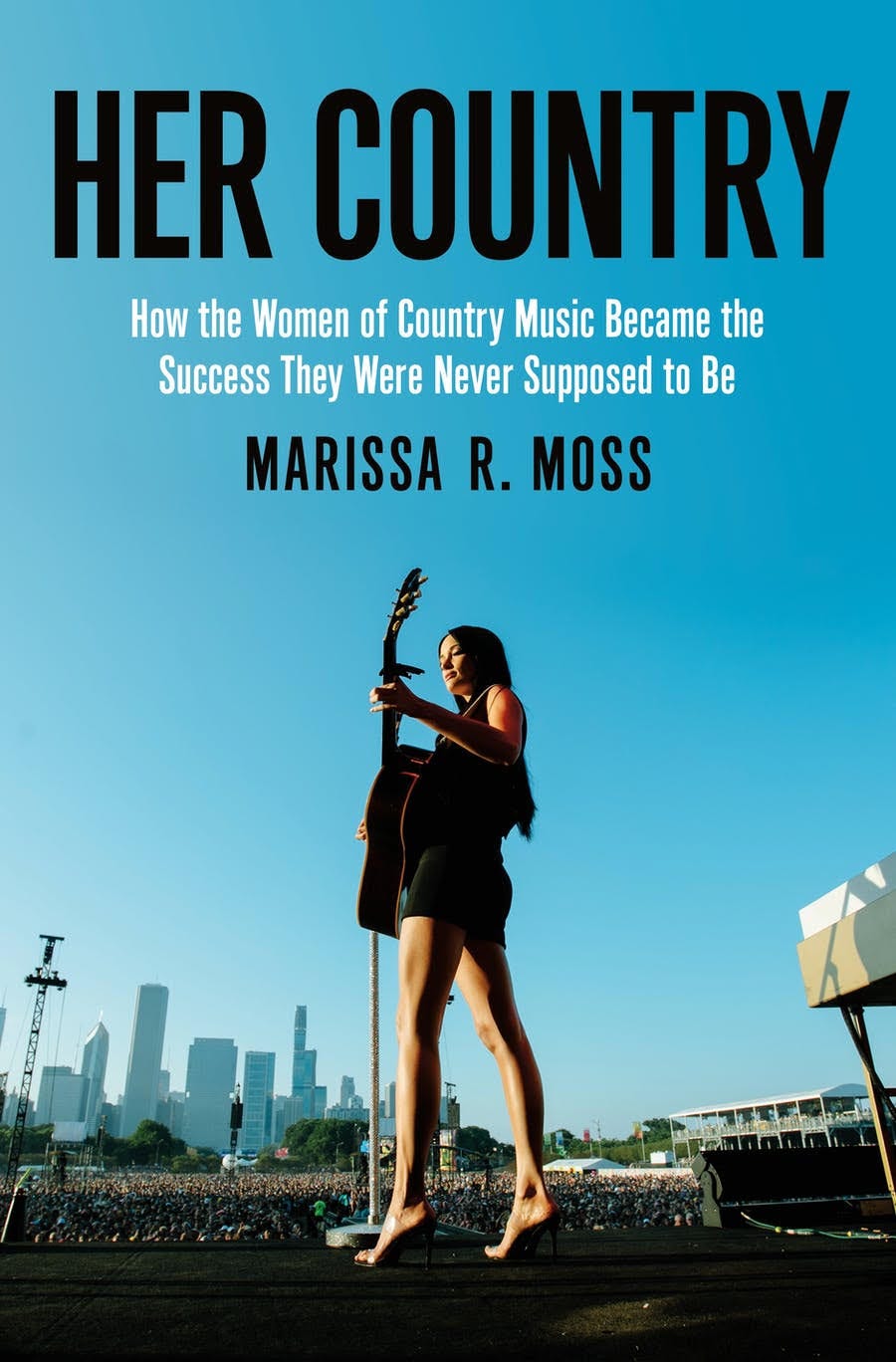

That’s bro-ification of country is starting to change now — and the genre, as a whole, is beginning (beginning) to have long ignored conversations about its own relationship with whiteness, racism, sexism, and spoken and unspoken modes of exclusion. And no one is cataloging this precise moment in country with the sort of honesty and fearlessness as Marissa Moss. I’m thrilled to have her in the newsletter today talking about her new book, Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be, which is just fantastic: engrossing, deeply reported, insightful, and a perfect gift for yourself or anyone else who, like me, knows the power of country music, and yearns for it to reckon with its sins.

You can buy Her Country here and follow Marissa on Twitter here.

First off: can you tell us about your route to doing the work that you do? People often assume that anyone who knows anything about country music is from a particular part of the country, and has a particular sort of background, and I love anyone and anything that explodes that understanding. So I’d love to hear how you came to love country music, first of all, and then secondly, how you came to write about it.

I definitely didn’t have a traditional country music upbringing, or traditional exposure to country music, and I think there are far more people like me out there who didn’t grow up in the country or weren’t raised with George Strait 24/7. I was born in New York and raised by a single mother in Manhattan, then Boston, then back to Manhattan — I loved Liz Phair and Fiona Apple and the Grateful Dead and Tribe Called Quest.

My dad did have a very strong love for country radio and would always play it in the car when he was dropping me back at my mom’s, and we made fun of him at first — but now I live in Nashville and write about country music and my brother plays bluegrass and old time music, and has for years Oonce my brother took that up a few decades ago, I really started to think it was cool. He bought me a Doc Watson double CD and The Day the Finger Pickers Took Over the World by Chet Atkins for my birthday when I was maybe a senior in High School, I can still sing most of those songs by memory).

I loved the Dead and Bob Dylan and I’m sure it was probably my brother who first urged me to look into their influences — and that sent me down a wild rabbit hole of country music. And then, around 2011, records by Caitlin Rose and Robert Ellis and Nikki Lane changed my life and my understanding of Nashville and country music as well, which is also around when I moved south.

I’d always wanted to be a music writer, but I realized pretty quickly that the way the press machine operates in country music was full of an uncomfortable load of bullshit and it was not for me. I’d come from political communications on various human rights causes with the American Foundation for Equal Rights (which worked to strike down Prop 8) and with Maria Shriver on her Women’s Conference in California, so I wasn’t about to set aside those guiding principles. But then Rolling Stone Country opened down here, and that was a godsend. I’m ever thankful for the then-editor, Beville, who responded to my cold email. She was not only a rare female music editor but a mom, which was so huge to me. I think I have only ever worked for maybe one other mom in music journalism? It’s a big deal when someone understands why you have to stop everything and run to pick your kid up from daycare when they spike a fever but doesn’t hold your existence of children as some kind of mark against your capabilities or intelligence. In music writing, I definitely feel as though my kids are a liability against my “coolness.”

I didn’t grow up in a country music home, but I grew up in a country music town — my station was 106.9, THE OUTLAW — and my memories of ‘90s country, like so many others’ memories of that era, were filled with, well, women: Faith Hill, Shania Twain, Deanna Carter, Mindy McCready, REBA….sometimes it feels like a different country (literally and figuratively) from the country of the 2010s in particular.

In my head — and I think your book underlines this — the backlash against The (then Dixie) Chicks’ (very mild) anti-war/anti-Bush comment feels like a watershed moment. But you also point to the ways that a lot of sentiments unleashed after that moment had been brewing for some time, and, in truth, had always been foundational to the genre and the industry that structures it. As you put it, “this isn’t just a story of sexism in music, it’s a story of America: of how misogyny and class permeate the most basic of threads, and how power supersedes decent and arts in the hearts of those who should know better.”

Can you walk us through the complexities of that backlash? How did it “discipline,” for lack of a better word, so many of the women featured in Her Country?

I always had this hunch that what happened to the Chicks would have happened with or without what happened on stage in London that night. And as I began to dig, I was surprised by how true I found that hunch to be – there was such a strong sentiment brewing in Nashville that they were getting too big for their britches or making people uncomfortable.

I don’t think Music Row or country radio would have let that kind of power and boundary-pushing go on forever without checking them. And by checking them, they had a really convenient way to tell any future women to stay quiet: “shut up and sing, don’t get ‘Chicked.’” Women were terrified. And you could be as vague in interpretation about this as you like: Don’t talk about inequity! Don’t talk about race! Don’t talk about politics!

I really wanted to break all that apart, how we got there, how the context of the boom in the nineties, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and resulting consolidation, the shift to patriotic songs post 9-11 and then what happened to the Chicks built this climate we then accepted as the way things are. It didn’t have to be this way, of course.

Can you break down the Gretchen Wilson/Patsy Cline dichotomy?

Thinking about those two together fascinates me, these two specific roles we are comfortable with women in country music occupying. Patsy Cline, of course, is known on the surface level as “standing by her man,” and Gretchen Wilson was accepted as a reaction to the popified versions of country stardom led by Shania Twain and Faith Hill (who, at that point, were not gaining any new friends in the country community by going what they perceived to be “full pop.”)

I love Gretchen, and I think she was very inspiring to a lot of women — but we are so specific with how women have to behave and exist in country music. If you want to be a bit more “authentic,” you need to either sing very traditional man-worshipping tunes or conduct yourself in a way that feels relatable to the boys: getting in the dirt, wearing leather, drinking beer and spitting tobacco. And of course, we can only have space for one of these – there is no room for a Gretchen Wilson and a Miranda Lambert! Just one woman allowed!

I think someone like Kacey Musgraves really threw off the balance of things in country music in a delightful way when she arrived — well, delightful for me, scary for others. She presented as very feminine and enjoyed fashion, but she toyed with ideas around sexuality. She was outspoken and traditional in a lot of ways. Of course, how much of this is available even to a Black country artist – can you imagine if a Black female country singer expressed that sort of rageful putting-a-basebal- bat-through-a-window-type-thing, like Carrie Underwood? My god would heads roll! We have to really examine that everything we allow in country music, even for women, is then set under the condition of whiteness.

Along those lines: You could pretty easily have written a book that just focuses on the successful, genre-bending white women of country music. But there’s an absence that becomes very present in Her Country and becomes one of the book’s guiding questions: Why are there no Black women in country? About half way through the book, you mention a conversation in which a casual observer asks basically that. How would you have answered before you wrote this book? And how would you answer now?

It’s a crucial question. Of course there are Black women who make and love country music — it’s rooted in Black tradition, after all! But they either don’t feel welcome in the genre or, more insidiously, aren’t getting signed or supported. The absence of Black women becomes very convenient for people who want to prove country is somehow a “white” art form. I have truly seen, shit you not, people claim that “Black people have hip-hop and white people have Country music and that’s not racist, that’s just fine!”

But then there’s the flipside: a few Black artists become popular, or show up on lists of Black Country artists. Then people in the business say “Look, there are five Black women here! Problem solved, no racism!” And they these Black women aren’t headlining festivals. They’re not being played on country radio. They’re both tokenized and marginalized at the same time, and it just keeps happening, like a constant loop.

I took myself to task when I wrote this book against my own work, particularly guided to think about how white feminism plays such a seminal role in keeping Black female artists oppressed. I haven’t always gotten this right myself, and I don’t feel uncomfortable saying that — it can be blinding to fight for crumbs, and that’s the point. It was essential to me to keep that idea as a hum behind anything I wrote in this book. No one is free until everyone is free and that’s as true in country music as anywhere else.

I’m trying to figure out how to ask this question, and it’s a knotty one. One of my great pet peeves is when people say they “only like alt-country, not any of that stuff they play on the radio.” Sometimes they’re trying to say that they like many of those featured in your book: people who didn’t fit into the neats boxes of established country music. But sometimes, too, there’s a real classism at work too, and the inverse of the exact sort of purity politics at work within established country music. How do you grapple with this in your own mind, or when others make similar comments to you?

Oh you nailed it, and this is something I wrestle with a lot myself. As much as I took the conservative radio establishment and such to task in the book, I wanted to also hold accountable that sort of classist, coastal perspective of “I like everything but country music.” It does a whole lot of damage as well. When I was in New York and began liking country music or told folks I was moving to Nashville, I saw so much of that response — a dismissal of country as high art, a dismissal of the south as a place full of awful people they don’t want to care much about. And I see echoes of this all the time when a horrible new law will come to pass — I’m thinking of the assault on trans kids in Texas – and folks in blue states will be like “sorry Texas, you deserved this” or something gross that dismisses everything and everyone inside the state. People do this with country music and country people. And then when country music and politics meld, it creates even more of a problem.

“For those reporting in the media hubs of New York and Los Angeles, [country music] was an easy target, a way to jostle the incoming president and the oft-stereotyped genre of country music in one fell swoop,” I write in HER COUNTRY. “Bush was for ignorant rednecks, they thought, so therefore country music must be, too. Easy peasy —t hey’d already established that the genre wasn’t something that could appear in the canon of a sophisticated music listener— ‘anything but country’ was the common bourgeois intellectual refrain, to the point that it would become commonplace study in sociology classes.”

I love that Americana exists — as Brandi Carlile says, it’s the island of misfit toys. But I don’t think that its existence should give folks permission to dismiss anything classified in mainstream country as crap. Part of what I absolutely wanted to do with this book is make a further case for this music not only as high art but true culture-shifting work.

Finally, who in country music is exciting you right now, and which specific songs of theirs should we listen to?

There is SO much exciting me in country music. I love Morgan Wade and “Wilder Days,” I love Margo Cilker and “Tehachpi,” and BOY do I love Joy Oladokun. “Let ‘Em Burn” by Emily Scott Robinson, “You Can Have Him Jolene” by Chapel Heart, all the wonderful work Miko Marks is doing, Leah Blevins, Brittney Spencer, Reyna Roberts, Hailey Whitters, Adeen the Artist, Kaitlin Butts, Allison Russell, Brennen Leigh, Kelsey Waldon who joined me at my book release party at Grimey’s in Nashville and who I absolutely love. Tyler Childers, Margo Price, Amanda Shires, Miranda Lambert, Charlie Worsham, Sturgill Simpson, Jason Isbell, Brandi Carlile and of course Mickey, Kacey and Maren. The mediocre can drown out the good, but only if you let it.

You can buy Her Country here and follow Marissa on Twitter here.

Looking for this week’s Things I Read and Loved? Want to hang out in the threads, or have the ability to comment below, or even just hang out the Country Music channel of the Discord? Follow through and become a Paid Subscriber!

Subscribing is also how you’ll access the heart of the Culture Study Community. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus equally excellent threads for Job Hunting (this week, we’re having an virtual job fair, it’s going to be amazing), join the Summer Flat Stanley Mailing Group, or hang out in Zillow-Browsing, Bikes-Bikes-Bikes, Nesting and Decorating, Puzzle Swap, Home Improvement/DIY, Running is Fun????, Advice, Ace-Appreciation, Books Recs, Home Cooking, SNACKS, or any of the dozens of threads dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. Finally, you’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I grew up hating country music (mostly because my dad forced me to listen to it in the car) but going to college in Texas helped correct my opinion. It people like Dwight Yoakum and Clint Black (and other neo-traditionalist if that era) that hooked me. I remained pretty in thrall through the early 90’s and it seemed like there were tons of great, interesting women country stars (Mary Chapin Carpenter was a legit, mainstream star for Pete’s sake) and then they just sort of disappeared (thanks to this interview I have some insight into why that happened) and it bums me out. I’m afraid I’m one those folks that Anne might get annoyed with these days. I love artists that embody to me the real spirit of country music (like Tyler Childers, Sturgill Simpson, early Neko Case, Margo Price and lesser known but absolutely vital artists like Laura Cantrell and Zoe Muth) but I have zero interest in Country radio. Part of that is unfortunately politics but as our polarization somehow continues to grow, it feels the politics of the Nashville machine are very different from my own. I mean just look at Kacey Musgraves. She should be a huge country star, played constantly and embraced by all fans but the machine can’t seem to abide that (of course she is a huge star in spite of Nashville). So I love the genre but hate the machine and the right control the industry wields over who gets hear what.

Given how obsessed I currently am with Morgan Wade thanks to a previous interview here, I'll be getting some more music off this one.

I listened to a ton of country music -- on the commercial country stations -- from the early 2000s to like 2011 (what changed was that I stopped doing long drives on my own) and thinking about that time I am now listening to Alan Jackson's "Drive" and contemplating where to go next in the nostalgia vein. But boy, your intro about that Toby Keith concert -- I always get stuck on what a really fun song "How Do You Like Me Now" is to listen to and what an absolutely mean-spirited song it also is. All she did was "overlook [him] somehow" and maybe, according to rumor, make fun of him, and for that he's spending adulthood celebrating that he's successful and she's had her dreams torn apart and has a miserable life. Before his political turn, Toby Keith told us who he was with that song, and it was such a good song it was too easy to ignore what it told us. Right now I want to listen to it and also it makes me feel kind of dirty. And while that's one of the clearest examples, that kind of, like, triumphalist masculinity where the shallow woman needs to be put in her place is such a strong strain in the country of at least the era I was listening the most. Thinking also of Montgomery Gentry's "She Couldn't Change Me," for instance.

Anyway, early on when I listened to country radio, the Philadelphia station I listened to had one show that would play alt country and Americana, which I also loved -- found Buddy and Julie Miller on there, only to mention them to my parents and learn that my parents had seen them live, which, way to spread the news, guys -- and I never knew for sure but it went off the air right around the time of the Chicks backlash, so I wondered.