Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are those who haven’t yet converted to a paid subscription. If that’s you, and you have the means, consider paying for the things that have become important to you. (If you don’t have the means, as always, you can just email me and I’ll comp you, no questions asked). Subscriptions make work like this possible.

Also, this week’s episode of WORK APPROPRIATE, out now, is all about add-on management, untrained management, and how to NOT be a shitty remote manager. Follow the magic link to listen on your app of choice and please join me in my noble quest to unseat the Joe Rogan Review podcast from the Culture charts — follow, subscribe, write a little ditty of a review, I appreciate you.

When I’m stuck in one of those moments where we used to, you know, hang out with our thoughts, but now generally turn to mindlessly thumbing our phones, I periodically realize I’ve wandered my way to the Delta App. Why? I’m obsessed with my SkyMiles. Not the number of them, not really. I just want to track whatever incremental progress I’ve made to the next medallion status.

Medallions are useful in that they generally improve your physical experience on an airplane, but the frequency with which I mindlessly check the app is wildly disproportionate to the medallion’s actual bearing on my life.

So why do I go there? Because Delta has figured out how to gamify their mileage program: turn it into a contest, of sorts, that can only be won by spending more time flying, spending more money on flying, or just spending more money with a Delta credit card, all so that I can….fly more? Listen, I love Delta Comfort. But I hate that I spend any time in that damn app.

Gamification is everywhere. It’s in your Peloton app (see above) your kids’ classroom, your Apple Watch, your DuoLingo. It’s responsible for our obsession with activity streaks, with “closing your rings,” with the (arbitrary) goal of 10,000 daily steps, with “getting all your 2022 badges” — and, more obviously, for our addiction to so-called “habit-forming” games like Candy Crush.

You may understand gamification on a basic level (of course this company wants me to use more of this product!). I did. But I needed Adrian Hon to really illuminate the how and the even deeper why of ubiquitous gamification — and tease out the differences between its “good” and “bad’ forms, and talk about how we see it (and resist it!) more clearly in our everyday lives.

Adrian is the co-founder of the gaming studio Six to Start, best known for the massively popular game Zombies Run! He’s also a Culture Study reader (paid subscribers, if you have questions for him, you know where to find him in the Discord) and if find this whole discussion as fascinating as I do, I can’t recommend his recent book — You've Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All — highly enough. This interview is weirdly addictive but as Adrian would say: you won’t regret it, not one minute, afterwards.

You can find Adrian on rapidly imploding Twitter here — or you can find him on Mastodon @ adrianhon@mastodon.social.

I want to know your game history: the first game that beguiled you, the first game that pissed you off, the games that made you think there might be something you wanted to do differently with games. What makes something an Adrian game (or a Six to Start Game)?

I was very lucky as a kid in the ‘80s and ‘90s, as my dad brought home computers (with modems!) from university for me and my brother to play on. So when I was just 11 or 12, l was being a complete brat in TinyMUSH, a “multi-user shared hallucination” text game that was more about socialisation than combat. Rather than banning me, the admins realised how young I was and encouraged me to be slightly less annoying online, which I’m eternally grateful for. One was even kind enough to give me a beta test invitation to Ultima Online, one of the very first massively multiplayer online roleplaying games.

Because we had PC rather than console games, I played a lot of strategy games and point and click adventures and role-playing games instead of platformers — that’s why I’m still bad at Mario and Zelda! I spent a huge amount of time playing the Civilization games; I played Civilization 2 all day for what felt like all summer and even wrote fanfiction about it. My first taste of game design was creating custom maps for Civilization and Command & Conquer. Some became pretty popular, so I ended up leading a team to create a “total conversion” mod of Command Conquer; predictably, the team quickly collapsed in acrimony, which was an instructive lesson in how not to do online teamwork…

I knew I wanted to become a game designer, but as far as I could tell, there were only three ways to get in. You could become a programmer, but I didn’t think my maths was good enough. You could become an artist, but — ditto. Or you could work your way up as a game tester, except I wasn’t actually that good at playing games. So I ended up studying experimental psychology and neuroscience at Cambridge University, which made my parents much happier than me going into the games industry. I did well enough to start a PhD in neuroscience at Oxford, but dropped out after a year — to enter the games industry.

Here’s how that happened: in my first year at university, I was entranced by a game promoting Steven Spielberg’s 2001 movie A.I., of all things. I read about it on Ain’t It Cool News, where someone had spotted on the movie poster a bizarre credit for a “sentient machine therapist” named Jeanine Salla. If you googled her name, you’d find her personal website from the year 2142. That website linked out a sprawling network of hundreds of websites, phone numbers, real world events with actors, all updating in real time over the course of a couple of months. Even though it was all obviously fictional, every single part of the game committed to it.

I couldn’t get enough of its mixture of science fiction storytelling, the real world, and gameplay. I ended up writing a novel-length walkthrough called The Guide, and got a free trip to Seattle to meet the creators. What was so exciting was that I realised I had all the skills needed to make this kind of game — an “alternate reality game” (ARG). I might not be an amazing artist or programmer, but by writing HTML I could design an entire fictional world and puzzles and mystery. I began writing a blog about designing ARGs, with the explicit goal of becoming the top hit on Google and eventually getting a job making them. It took three years — and it worked. I became the lead designer of Perplex City, one of the biggest ARGs ever, and later co-founded a new games studio, Six to Start, in 2007 with my brother.

A Six to Start title has always combined those three things: gameplay, storytelling, and the real world. In our first project, We Tell Stories, we worked with six of Penguin’s top authors, including Mohsin Hamid, Naomi Alderman, and Nicci French, to create stories that could be told only on the Internet, like The 21 Steps, a Google Maps thriller, and Alice in Storyland, an ARG. We ended up winning Best in Show at SXSW! In the next few years, we made more genre-busting games for the BBC, Channel 4, and Microsoft, and we worked with Disney Imagineering on ideas to turn their theme parks into ARG-like adventures.

But we’re best known for Zombies, Run!, a running game and audio adventure for smartphones that makes exercise more exciting. It’s co-created with Naomi Alderman and it’s become one of the most successful forms of gamification ever, with over 10 million players since it launched a decade ago. It’s rare to make something that’s so original, while also being commercially successful and unequivocally good for everyone who plays it, and I’m so proud of the entire team who made it.

One summer, when I was in elementary school, my mom came up with an elaborate “marble” system for the summer: you could earn marbles for doing things like reading, or going on a walk, or doing a load of laundry, or even, if I’m remembering correctly, playing nicely with my younger brother. You can then “spend” marbles on an hour of television, or a ride to the swimming pool (instead of biking/walking), or, with a whole bunch of marbles, a new Gameboy game.

My brother and I talk about this system with great fondness, but we were essentially gamifying summer. (This was also a time when we were playing a fair amount of Zelda, so I think the entire system made total sense to us for other reasons, too).

When you think about the spread of gamification into so many corners of our everyday lives, what is lost, and what is gained? What did we lose through gamifying summer, and what did we gain? (I know that my mom certainly gained a way to make us stop constantly asking for things) (I suppose this might also be a great time for a very straightforward definition of how you think of gamification)

Your mom’s marble system is a good example of smaller “analog” gamification, which can help structure activities and set goals and measure progress, especially when that progress is hard-won and toward a journey whose end is more abstract. My swimming lessons had similarly low-tech gamification, where we got badges for being able to go 25m without stopping, or for being able to pick a brick up from the bottom of the pool. These kinds of achievement badges and scores can be genuinely useful as training wheels for things we really care about doing.

A virtue of small-scale gamification is that it’s easily customised and involves human judgment. Your mom could easily change the goals or give you more marbles for extra effort. It’s a human who decides whether a goal has really been achieved, like the swimming instructor who made sure I wasn’t pausing for too long between laps on a test.

The problem is when gamification — the use of ideas from game design for non-game purposes — expands beyond the bounds we consciously set. It’s one thing to buy Nintendo’s Ring Fit Adventure to intentionally gamify your home exercise. It’s another to buy an Apple Watch because it’s the only smartwatch that Apple allows to be fully integrated with the iPhone, and you start getting notifications just before midnight badgering you to “close your rings” by going for a run, or to always be offering shiny achievements for increasing your calorie burn month after month. This kind of scaled-up digital gamification quietly substitutes the goals of corporations (maximising engagement and profit) in place of our own goals. Worse, it removes human judgment entirely; there’s no-one at Apple who can decide you deserve a day off your calorie goals.

What offends me as a game designer, however, is how so much gamification made by corporations simply isn’t fun. Instead, it’s the thinnest, most thoughtless layering of aesthetics and mechanics from game design onto an unappealing activity. I hated cross country running at school, and I’d still have hated it if my teachers made us use Strava to get virtual achievements and compete on a digital leaderboard. But I loved playing five-a-side soccer with my friends every weekend – and we only kept score so that if things got too lopsided, we’d swap players.

So when your mom gamified your summer, maybe it served as training wheels to help you develop a genuine love for reading and a real appreciation of the value of doing chores. Or maybe it led you to cynically doing the easiest chores and reading the shortest books to get the most marbles. What’s important is that your mom was in charge and could change the system if she felt it was getting out of kilter. When we surrender the control of our motivation and the judgment of our performance to corporate-owned gamification, however shiny and well-marketed, we need to be damn sure it’s designed for our benefit.

I think people generally understand the way that Candy Crush represents a sort of peak gamification. But I’m particularly interested in the gamification of smaller corners of everyday life: the “progress bar” on a LinkedIn profile, for example, or the Peloton streak. What are your favorite examples that always make people kinda bonk their head against the figurative wall when they figure out that it’s been gamified in some way? (For me, it’s always the damn Delta App) And how (and why!) does gamification so often invisibilize itself?

My partner’s mom got into Duolingo during the pandemic to learn French and recently, while visiting her daughters, she abruptly disappeared into another room from which various Duolingo sound effects emanated. Given they hadn’t seen each other for months and were all eager to catch up, this was quite mysterious. It turned out that a Duolingo “XP Happy Hour” notification had popped up on her phone and she wanted to get extra XP (experience points) by completing as many lessons as possible. Maybe using Duolingo really was the number one thing she wanted to do right at that moment and she was grateful for its reminder, but I suspect it’s more that Duolingo’s gamification had instilled an artificial, unnecessary, and unhelpful sense of FOMO.

I think everyone has one of these stories where they start gamifying an activity out of curiosity, and eventually that quantification and gamification ends up subsuming whatever they were hoping to get out of the activity in the first place — like people who buy a Peloton to get fit and end up overexercising and hurting themselves after becoming fixated by its achievements and leaderboard and streaks.

Where I bonked my own head against a wall was playing Assassin’s Creed Unity. I love the Assassin’s Creed games, there’s nothing quite like sprinting over rooftops in Florence and Paris and silently stabbing baddies from the air. There was always busywork — treasure chests to unlock, trinkets to collect, secrets to find — but it never overwhelmed the main story quest… until AC Unity. I still shudder when I think of opening AC Unity’s map and seeing so many icons for busywork sidequests that they obscured all of Paris apart from the Seine.

There are a couple of reasons why the developers added these sidequests. The first is because some players genuinely like them — they like to zone out and get those 128 collectible cockades. The second is that sidequests inflate the time it takes to complete all the tasks in the game, which is helpful for marketing (many think a 60 hour game is “better” than a 20 hour game). Unfortunately I’m one of those people who, when they see a map with five hundred icons on it, is compelled to tidy up those icons by completing all the quests, which meant I spent so long playing that my enjoyment of the game was largely extinguished. You might think it’s weird that I count this busywork as gamification since it’s already inside a video game, but it’s in the service of a non-game purpose — maximising engagement and profit, as ever.

Designers and gamers call this kind of repetitive busywork “grinding,” which is perfectly evocative of its needless, anti-fun nature – and yet it’s surprisingly persistent in modern games, and I suppose, life. I think it’s because we find it so painful to talk about what it is we really are looking for in games. Sometimes we want to just sit back and mindlessly run around Paris because we’re so exhausted from work. And sometimes it’s to get an intense, beautiful, imaginative experience. Bad gamification conflates those two things and exploits them for profit.

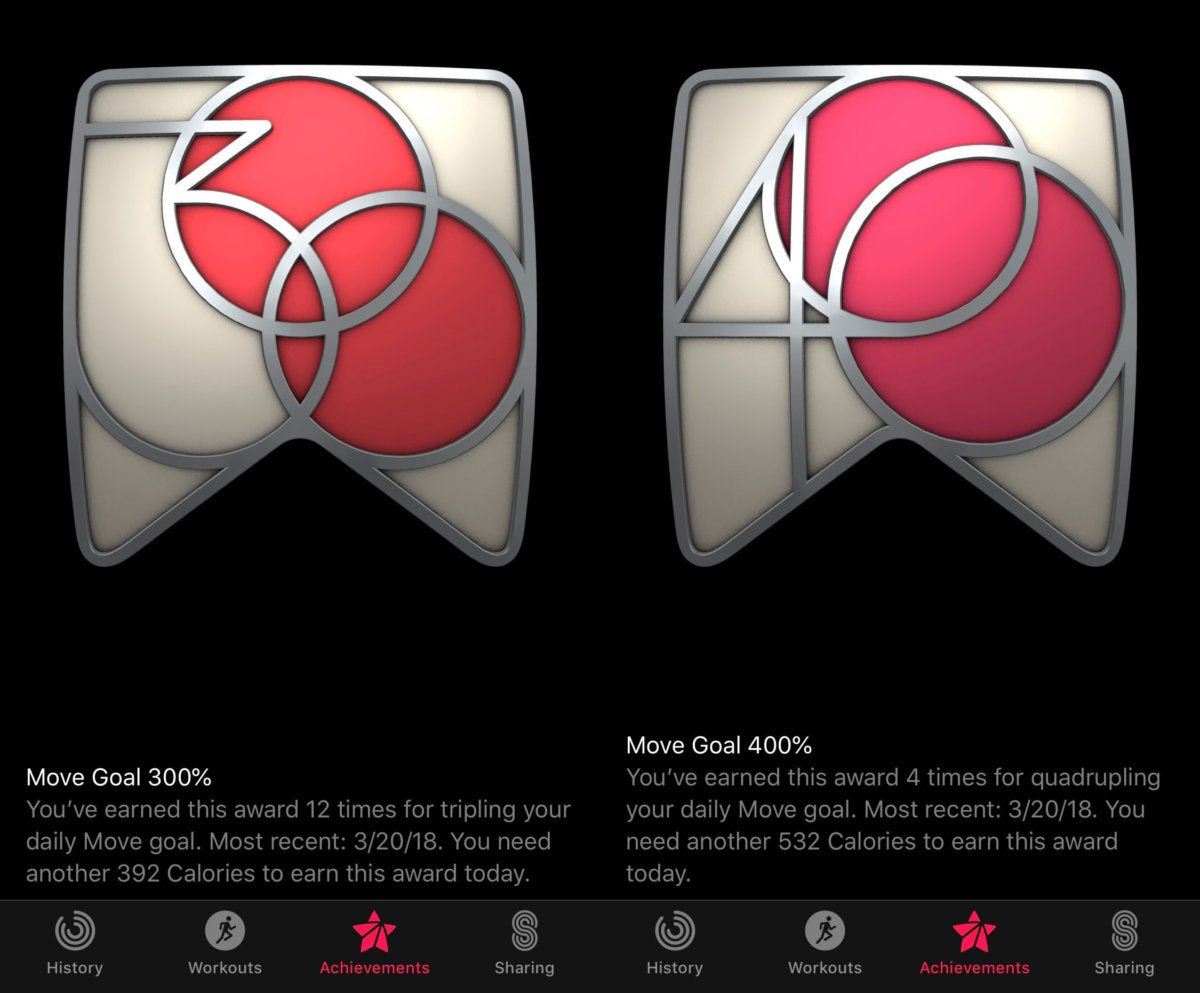

I really appreciated the way you discussed how streaks, particularly on exercise apps and devices (see: the rings of Apple Watches) have come to terrorize us — whether through arbitrary completion goals (the famous 10,000 steps) or simply by appealing to perfectionist tendencies. A friend recently told me about how sad she felt when she broke her Peloton weekly streak because she was in the hospital, caring for her husband, but the streak itself had come to emblematize her feeling that she was able to take care of herself. I recently wrote about how contemporary calendars aren’t built for rest or caregiving or acknowledgement of disability or differing ability — and how much of that, too, is a reflection of the thinking and norms of the engineers who designed them. How do you see that playing out in games — and is there a way to design differently?

All of this comes down to the capitalist belief that life should be a straight line that keeps going up. Every month, my Apple Watch entices me with a shiny badge if I exercise more than I did in the previous month, despite the inevitability of me eventually getting ill or tired or needing to take a break. So much corporate gamification sees that inevitability as a literal failure rather than a part of what it means to be human.

I also see this belief play out in games that have no end, which is how a lot super-profitable “games as a service” operate, by getting continuous revenue rather than a one-time sale. These games are designed to keep players playing forever, enticed and retained with limited-time quests and progression loops and “battle passes” that can take hundreds of hours to be completed. Their designers always claim they are providing entertainment for practically free, if measured in a money-per-hour basis, but that belies how they’re designed to maximise lifetime revenue such that it’s possible to spend hundreds if not thousands of dollars per year on “optional” items; and also it ignores the quality of the time spent, as if a 20 hour movie were obviously better than a 2 hour one.

The way to design these things differently is to account for and respect the rhythms that exist in our lives. That means removing streaks from most apps and games: we shouldn’t reward people for running or playing or even writing 100 days in a row. Designers should recognise that people will need breaks and ensure their apps don’t punish people for being human.

When it comes to my own games, I want to ensure my players don’t regret the time they’ve spent on my creations. I don’t want someone to one day realise “hey, I actually hated how Zombies, Run! made me run 100km in a month for a badge!” And as the designer, I’m in a much better position to know about potential regret than my players, who don’t know what kind of loops and incentives I may have built to “retain” them as long as possible. I spent years playing FarmVille and CityVille, and the moment the spell was broken, I instantly regretted practically every second of that time. So now I stay away from games like Candy Crush because I don’t want to play a thousand hours on them, but I’ll happily play the mechanically-similar You Must Build A Boat or 10000000 because I know I’ll be done with them after a few hours. That said, there are other games I’ve spent a lot of time on, like Mario Kart and Team Fortress 2 and Overcooked, and I don’t regret a minute of that time.

The New York Times recently published a classic “tech mea culpa” opinion piece by William Siu on this very subject. Siu is a game designer who’s personally made millions from his mobile games, and it has this incredible bit:

“For a long time, I didn’t see a problem [with making habit-forming games]. I saw our mission as bringing joy and entertainment to players. This changed when my two toddlers became old enough to take an interest in playing the very games I had built.”

Total “I didn’t see sexism until I had daughters” energy. We know better. Game designers know better. Product designers and engineers know better. So they need to do better.

Can you broadly talk about Class Dojo? What is it (for people who don’t have kids in systems where it’s used), why do you think it’s been so broadly adopted, and what’s at risk with internalizing a constant “growth mindset?”

ClassDojo is an app used in 95% of US schools, and it does two main things. The first is provide a private social network for teachers, students, and parents to share messages, photos, etc., which seems pretty unremarkable.

The main attraction, however, is its behaviour management system. Teachers can install the ClassDojo app on their phone and set up screens for all the students in each of their classes. They can then award or deduct points from students for any behaviours they like, such as +10 points for good teamwork, +5 points for being quiet, -10 points for not following instructions, or even in one real-world case, going to the restroom during class. So in a way, ClassDojo becomes a gamified disciplinary system.

To be fair, a lot of teachers and parents like ClassDojo. They say it can motivate disruptive and disinterested students, and compare it to the classic “marbles in a jar” system. Does it work? There isn’t a lot of evidence either way. Some studies suggest it can improve classroom behaviour, though at the same time making students more negative about their classes. But even if it works, are we happy about how it works? The UK children’s commission said it “contributes to a practice where children are increasingly being monitored and tracked around the clock, which may impact upon their development and experience of childhood,” and some parents talk about how terrified their children are for slipping up and losing points.

Once of ClassDojo’s defences is that they’re trying to promote Prof. Carol Dweck’s “growth mindset” in students. The “growth mindset” says that ability and intelligence and talent come from hard work, curiosity, and perseverance rather than a “fixed mindset,” which believes it comes from innate, unchangeable traits. So if you squint, you can convince yourself that gamifying schools by giving students points for working hard and persevering will help promote a growth mindset.

Assuming that’s true — which is arguable, since it might instead make students conflate ability and intelligence with maximising ClassDojo points — it’s not clear that a growth mindset helps students at all. Two meta-analyses published in 2018 found that interventions designed to increase students’ growth mindsets only had weak effects on their academic achievement, and in 2019 a large randomised controlled trial found the growth mindset theory made no impact on literacy or numeracy progress. Maybe classroom environments make it difficult to teach growth mindsets well, or that our current measures of academic achievement aren’t detecting its effects — but at the end of the day, the “growth mindset” angle is not a great defence.

One of the things I appreciate most about the book is that it has a hell of a “so-what.” As in: here are all the ways gamification has spread into our lives. And here is why it really, really matters. As you write in the conclusion:

“The gamification we encounter most often and most conspicuously in our lives doesn’t deliver the fulfilment or progress it promises. Instead, it maintains stasis. It keeps workers in line, funnelling profits to those who already have capital. It encourages us to study or train or play for goals that aren’t truly our own. And it reinforces the idea that the world is a game, whose rules are to be worked around but not changed. Even utopian gamification is remarkably conservative, a consequence of its funders’ politics, and of their reluctance to challenging our existing economic and political systems.”

Can you talk more about how this frustrating form of stasis and the concept of “soft lock?” And an even harder question: how can people not only make gamification visible in their own lives, but *resistable*?

Since my book came out, some interviewers have asked “how can gamification be bad if you’re gamifying fitness?” The short answer is that good gamification is good and bad gamification is bad, and unfortunately the vast majority of gamification is bad.

It’s bad when it’s designed lazily, with the assumption that layering points and badges and turning everything into a competition with prizes and punishments is all you need to make something fun and exciting. It’s bad when it’s designed to exploit or fool us, like brain training games that wrongly claim they can stave off Alzheimers; or Uber and Lyft and Amazon’s gamification that manipulates their workers to do more for less.

And it’s especially bad because it’s using the aesthetics of an art form that we’ve always associated with freedom and joy and fun. We’ve grown up thinking that when we see quests and XP, we’re in for a good time. And we believe, mostly correctly, that board games and video games are designed to be fair. But bad gamification exploits that belief. It keeps us working ever faster and harder in exchange for game-like trinkets and bonuses, while the material circumstances of our lives remains exactly the same.

That’s where the idea of “soft lock” comes into play. In video games, this is when a player gets into a situation where they haven’t died or failed, but no further progress is possible, like if your character falls into a deep pit with no exit. In that case, the only solution is to restart the level or restore a savegame. It’s not always as obvious as falling into a pit, though. Sierra’s point-and-click adventures like Space Quest and King’s Quest were notorious for this, where you could miss something minor at the start of the game and play for hours without realising there’s no longer any way you can complete it.

So in a world where everything is gamified, we can end up in a real life soft lock, but one that’s been designed deliberately to create stasis, where we’re distracted with flashy points and endless competitions that only provide the illusion of progress. Worse, there’s no way to appeal to a human, since your only interface is a gamified app — but unlike a game, there’s no way to reset.

The way we resist this is first to see it. Gamification has grown so rapidly and is turned on by default in so many apps and devices that it’s easy for us to normalise it, or to assume it has no effect. Instead, when Duolingo interrupts you in the middle of dinner with the promise of extra XP, you should think about what kind of behaviour they’re trying to encourage in you, and whether you want to do that, and who’s really benefitting from this interaction. When Starbucks gives you a time-limited Star Challenge worth extra loyalty points, recognise that as corporate gamification designed to engage and retain you and to increase their profits. Maybe that works in your favour this time, but maybe you only want that extra frappuccino because of the notification and because you want that extra level.

A lot of this gamification can be deactivated or at least muted, by silencing app notifications or changing settings, but some of it can’t. So there’s only so much we can do as individuals, and that’s where regulation should come in. The SEC is considering regulating gamification in consumer financial trading apps that might be encouraging users to make more trades – and more risky trades – than they intended; and various countries including Belgium and the Netherlands are seriously considering banning gambling-like lootboxes in video games. In the UK, the Information Commissioner’s Office now recommends against using gamification to erode children’s privacy.

We already have regulations to protect us from being exploited and misled. These regulations need to be enforced more consistently and should include gamification. That absolutely shouldn’t mean banning gamification everywhere, but we deserve more transparency and choice in the ways our apps and workplaces and schools are trying to manipulate our behaviour.

It really isn't normal for points and leaderboards and achievements to be attached to everything we do. That’s why I wrote my book — to highlight just how widespread and how dangerous it’s become, and to make people a little more skeptical of its claims. But despite all of this, I’m still an optimist – if I weren’t, I wouldn’t be making games! The very best gamification really can make learning science and programming more fun; it really can make practicing the guitar more enjoyable; it really can make exercise more exciting. I just wish we devoted our efforts to making that kind of gamification that enriches people’s lives and fully aligns with their interests, rather than gamification that pins people in place and bleeds them out.

You can find Adrian’s list of ridiculous ways for Twitter to gamify (and Elon’s actual response) here, and you can buy You’ve Been Played here.

Do you want access to the weekly link roundup and “Just Trust Me?” Do you want to be part of a community figuring out how to care for one another, even from afar? Or maybe you just want to feel like you’re supporting content that’s valuable to you. Here’s how you do it:

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. For example: on November 20th, the Job-Hunting thread of the Discord is hosting a new fangled CAREER DAY at 3 pm ET/noon PT — meant for people who are thinking about new jobs but are still kind of thinking “I have no idea just how many TYPES OF JOBS are out there.” (This is the 2nd Career Day; the first was SO GOOD).

Plus, there’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece and the latest episode of the podcast, plus really useful threads for Job-Hunting, Houseplants, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Fat Space, Productivity-Culture, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

"ClassDojo is an app used in 95% of US schools..."

This is horrifying. As an educator (at a school that does not use ClassDojo) this deeply creeps me out, maybe because I hate gamification and I hate streaks?

Nothing is more demotivating to me than "streaks." I intentionally break my Duolingo streak every Shabbat so I don't get a high number and feel guilted into paying $4 to fix it. (I could squeeze in a lesson on Friday morning and Saturday night to keep it... but I won't.) I find the whole thing so demotivating and depressing.

What a fantastic interview!

I'm not a game person but am perhaps overly fixated on my Strava logging.

One way I've found to remedy this is focusing on counting/tracking the things that add joy, but not in a streak/don't break the chain/habit tracking way way. I have the Counter app on my phone and log things that make me happy - time outside, social events, books read to my kid, moments of connection with my husband that aren't chores or logistics focused. So I don't feel bad if I don't do something for a few days, it's not as stark as that, but I get the dopamine hit from the thing I added (coffee with a friend, curling up on the sofa with my son and a big pile of books) and from adding a coutn to the app. In some ways, this is a bit obnoxiously quantified life but the things I track are things I know bring me joy rather than being punitive (ie. calories burnt, days without sweets or something).