This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

When I was in eighth grade, you knew something was cool because Jessi, whose name I have most definitely changed, said it was cool. Umbro shorts: Cool. White socks pulled up to your knees: Cool. A white shirt with a simple Calvin Klein logo: cool. A striped knit Mossimo shirt from the men’s section of The Bon Marche that she shoplifted: cool. An oversized polo from your dad’s closet: also, weirdly, cool.

Jessi was, without doubt, the most popular girl in the grade. I don’t know how we knew this, we just knew. Power puddles around people, a mix of perceived beauty and class. She was cool because she had an older sister, because her dad lived in a house with an elevator, because she dated a guy two years older than us who could drive. Particular to the sort of place where I grew up, she was also cool because she knew what crank was, and I didn’t know until at least a solid decade later that crank was meth. She had long, tight black curls but never used the scrunchie on her wrist. She would tell us stories about how her Dad wanted to send her to boarding school. One time she started a school-wide epidemic of self-induced fainting. She asked to copy my Earth Sciences homework and I let her.

For a year, maybe two, I understood cool through Jessi’s discerning and limited eye. She’s wasn’t playful or inventive with her style. She just had money — or, this is key, she had parents who thought it was important to give their kids money for clothes — and, when she didn’t have that, she had the gumption to steal what she wanted from the extremely small but extremely important Lewiston Center Mall. The way she spread her style was through duplication and affirmation: consciously or not, she was propagating a uniform. She’d literally say “cool shirt” if you showed up the next day in the same shirt she’d worn the day before.

A girl in the grade a year older than us had what I could see, even then, as a wild, bold, enviable style: she used bleach to put handprints all over her jeans! I tried it, in secret, in my family’s storage room, and it did nothing (I was using color-safe bleach). But her presence and confidence (she was somehow still popular, despite the fact that she seemed to own zero Mossimo shirts, my mind was boggled) inspired me to deviate, however slightly, from Jessi’s norms. I paired white bike shorts with a white, short-sleeve button-down of my dads that had thin, light purple. I don’t know what made me think this but I looked in the mirror and thought: maybe this is cool.

I rode the bus to school, still holding tight to that feeling. I walked off the bus and towards the spot near the Maggot Wagon that sold pizza pockets and gum to kids where Jessi held court. She didn’t make fun of my outfit. She just didn’t say anything at all. And that was enough. I wore an inside out sweatshirt the rest of the day (yes, this was cool) and willed myself to dissolve without a trace. I can’t remember what I wore the next day but I know who I was then, and that person would’ve worn a Mossimo shirt as a form of redemption.

Most women I know talk about the outfits of middle school the same way they talk about an embarrassing and lasting injury. The memories are so vivid: the brands, the clothes themselves, the dressing rooms where we tried them on, the well-thumbed catalogs, the mortifying trips to the cash register with parents or the slightly more confident ones with our small wads of babysitting money.

Those memories are different than the sensory ones of elementary school clothes: the stiff bend of the decal on a shirt, the tightening comfort of a shirt I refused to stop wearing after a growth spurt, the crushed velvet of the Christmas dress my mom made for me that made me feel unmistakably fancy. As Virginia Sole-Smith put it earlier this week in her excellent newsletter on style and the privilege of blending in, for many, these are the years of “loving clothes on our own terms.” Every morning I woke up and wore what I thought was great. I looked great in my crooked headband, I looked great in skirt covered in spare buttons (!!), I looked great in the dress with a skort that allowed me to flip on the monkey bars. And what made those clothes feel great is that I chose them.

With each passing year, those choices were more and more shaded by what I saw in my classroom, in catalogs, and on television. But they still felt, fundamentally, mine — which is part of why I delight in photos of me from those years. I hadn’t learned what it felt like to suck in your stomach eight hours a day, to guard your cleavage, to be nervous about your bra strap, to become vigilant to the ways that your body could betray you, or how clothes held the capacity to make you feel bad about yourself every day.

Because the reality of my eighth grade fashion, dictated by Jessi, was that I never felt good. I felt passable. The clothes communicated nothing about me save sameness, and that sameness doubled, in those years of abject insecurity, as confidence. Sameness was my discipline, and I applied it to my body and my behavior with the same rigor that I applied it to my clothing choices. It was a privilege, I realize, that I was able to approximate it. And like so many privileged positions, it was drained of pleasure. But I psychologically injured myself and others, knowingly or not, to maintain it.

The memories of these years remain vivid because the bruises don’t fade. I go over them in my mind and the shame returns. Yours might be tethered to the way a parent or grandparent talked to you about your body or how clothes should look on them. You might have your own Jessi, a main character in the story of your life even though she probably doesn’t even remember your name. Or maybe a boyfriend or girlfriend who only allowed you to understand confidence as through their eyes. Whoever they were, they controlled how and when you permitted yourself to feel good.

How long does it take to recover and re-anchor your own sense of style — and sense of self? When do we, as one reader floated in an Instagram thread last week, gain the confidence to dress as if we were immortal? Ask me in a year, five, ten, thirty. Because this shit is so hard to unlearn.

Case in point: a few months ago, I was talking about the abundance and confusion of Jeans Right Now, and what we are “supposed” to be wearing this season. When someone pointed out that saying I found a particular style of jeans “unflattering” on me was, intentionally or not, inherently fatphobic, I recoiled. Some things look good on my body type, I remember thinking. That is not a value judgment.

But friends: it is. “Flattering” is the vernacular of body discipline. It is a way of convincing ourselves that an item of clothing is or is not for us, simply because of how someone else thinks a body should look in clothes. If that sounds weird to you, it’s because you’ve been swimming in this understanding of how your body should look in clothes your entire damn life: that legs should be long, breasts contained, skin smoothed, waists pronounced, measurements proportional. That if something does the opposite to our body, it should be rejected.

As stylist Dacy Gillespie, who runs Mindful Closet, told Virginia Sole-Smith, “the entire business model of many stylists and fashion brands it to point out perceived flaws on people’s bodies and then promise they know the answer to “concealing” those “flaws.” In other words: to tell us the narrow sliver of clothes that “flatter” our body type, aka make it look as much like the (slim, flat-chested, contained) ideal as possible.

This advice is valuable only because we’ve been “flattering” into a scarce resource. Tailored clothes (which can even mean the difference between a “Large” and a specific numerical size) are often the most “flattering” — but also, if you don’t know how to sew, the most expensive. And again, even if you can buy the right clothes, they’re still often only “flattering” on a certain type of (usually white, always slim) body. That’s the primary source of their power: their ability to exclude.

Here, I think of Tressie McMillan Cottom’s work on the idea of beauty:

All girls in high school have self-esteem issues. And most girls compare themselves to unattainable, unrealistic physical ideals. That is not what I am talking about. That is the violence of gender that happens to all of us in slightly different ways. I am talking about a kind of capital. It is not just the preferences of a too-tall boy, but the way authority validates his preferences as normal. I had high school boyfriends. I had a social circle. I had evidence that I was valuable in certain contexts. But I had also parsed that there was something powerful about blondness, thinness, flatness, and gaps between thighs. And that power was the context against which all others defined themselves. That was beauty. And while few young women in high school could say they felt like they lived up to beauty, only the non-white girls could never be beautiful. That is because beauty isn’t actually what you look like; beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order. What is beautiful is whatever will keep lake parties safe from strange darker people.

The ability to own “flattering” — like beauty — is always about power. And, as McMillan Cottom points out, it is also always about social reproduction. That was true in the eighth grade, where Jessi used her preferences to shore up her personal power, but it’s also true of the invisible iterations of the ‘Bama Rush wardrobes and the uniforms of Christian Girl Autumn.

There are ways of decentering that power — and yet, as McMillan Cottom and countless others have pointed out, they often result in new and damaging hierarchies of their own, often ordered (surprise!) in proximity to whiteness, slimness, gender normativity and/or transnormativity.

This is all deeply depressing, of course, the same way that any journey into the heart of why we act and behave the way we do is often deeply depressing. It suggests that we are no longer our eighth grade selves and yet still very much subject to the power plays of our eighth grade years, just with slightly thicker skin and better coping mechanisms and more distractions. But I also think the dominant, hegemonic understanding of fashion, cute, even flattering…it’s rupturing.

It started with the expansion of normative centers — they may reproduce existing norms, but they also spread the ideological fabric thinner. And it continues with ongoing, escalating articulations of what it looks and feels like to inhabit a body — and clothe it! — in flagrant opposition to those norms. All these Instagram and TikTok accounts, so accessible and so easily amplified, are asking and answering the questions mainstream media has always ignored: What does it look like to dress with the same joy as you did before you became conscious of your body? Is it possible to choose an outfit with the underlying supposition that you is beautiful in it, is lovable, is sexy, simply because you have decided it is? What would it look like to talk about clothes without talking about bodies — which is to say, without talking about “flattering”?

There’s Kate Sturino, whose #supersizethelook feature is extremely popular, and Mindful Closet, mentioned above, whose explicit goal is to “help women release the patriarchal standards they've been conforming to and uncover their true, authentic personal style.” But there’s also Mikaela Pabon, owner of Dressed in Joy, and Marielle Elizabeth, who specializes in “slow fashion for fat babes,” and Carla Rockmore, “celebrating the self-expression of fashion in 50+.” There’s Becca Murray, whose aesthetic is “body neutral cool aunt,” and Jeffrey Marsh, who’s expanding the fashion of nonbinary joy.

There’s Sierra Schultzzie, who makes me laugh a lot, and femme dandy sewist Rare.Device, and the exquisitely uncatagorizable artist Rachael House. There’s fat liberationist and comedian Sofie Hagen, and Fattily Ever After author Stephanie Yeboah, and fashion accessibility activist Sinéad Burke.

And that’s just a corner of the larger landscape. People sometimes talk about the idea of an “influencer” with condescension, as if influence only works the way it did when we were in 8th grade. You can also be influenced in a way that totally blows up your norms. You can be influenced to trust your own damn self. As one reader put it last week, when I asked for even more suggestions of accounts to follow, “I want items that fit regardless of the size, made of natural fibers or mostly natural, things that make me feel something, and not uncomfortable. These last few years have taught me: I’m alone and I’m OK. I’m my own influencer now.”

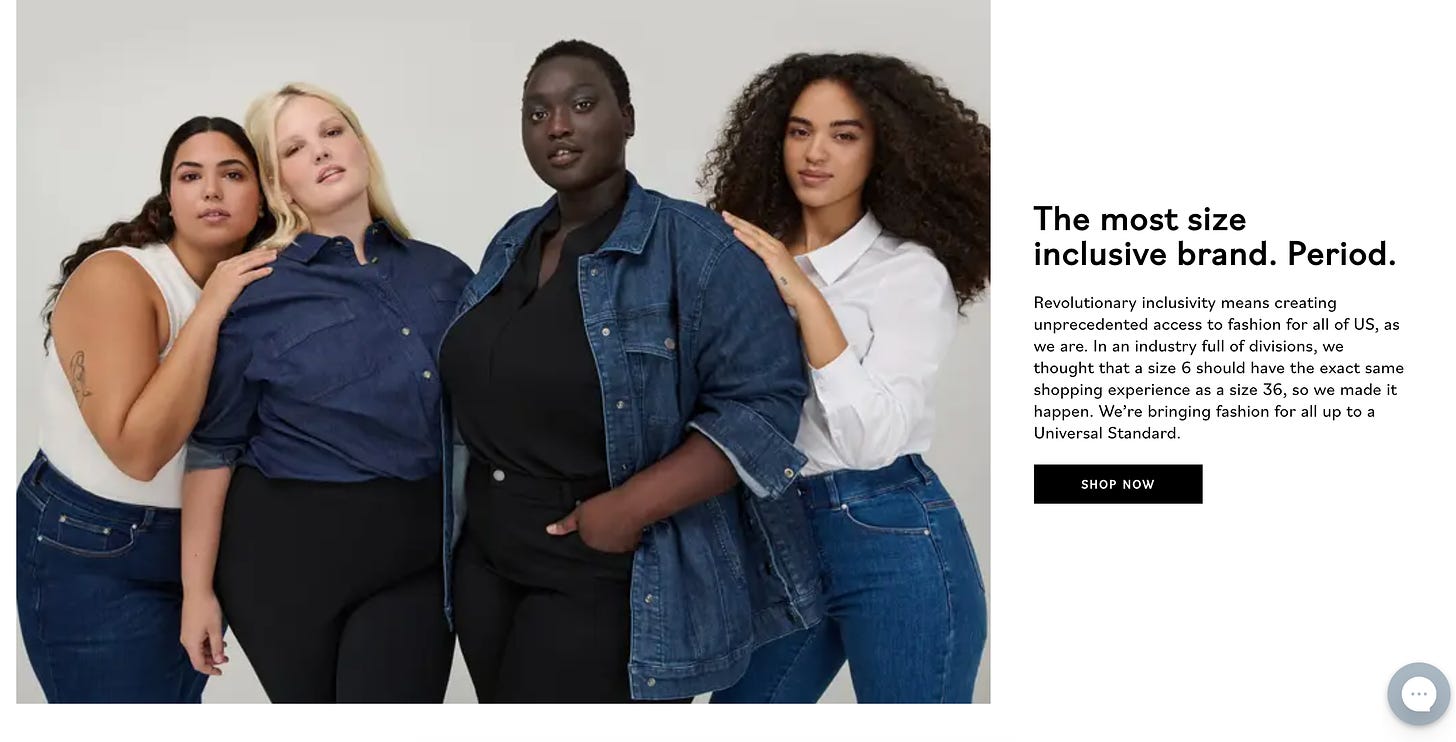

And then there’s the clothes themselves. There is so much room for brands to improve when it comes to actual size inclusivity: e.g., sizes above 22, and actual photos of models in those sizes, and those sizes available in stores. But if you’re around my age, it’s stunning to open up the website for a traditionally “straight sized” brand like Madewell, Anthropologie, or Lululemon and see their clothes on bodies that aren’t a sample size….and ever more brands, like Universal Standard, built on the supposition that every body is a fashionable body. This sort of inclusivity can feel, as their website puts it, revolutionary. But what if it is the future?

I’m not hopeful about much for the generations to come, but I am hopeful about this: that our disciplinary norms will continue to dilute, and our compasses of beauty will continue to reorient back to the self. That others will not be forced to learn what we’ve spend years and decades unlearning. That our bodies will be the least interesting or remarkable thing about us. That power will arrive not because we know how to dress like others, but because we know how to dress as ourselves.

What does that mean in practice? I’m beginning to know, in some negotiated and fumbling way, what that means for me. Detangling what “others” thinks look good from what I think looks good is a difficult and daily practice! But I’m so hungry to hear what it means for you.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version.

Subscribing is also how you’ll find the heart of the Culture Study community: in weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus the channel for Job Searching, and equally excellent spaces for non-toxic-child-free, chaos parenting, chaos yardsale, spinsters, queer secrets, and so much more. And if you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. You’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

As a fat lady, I felt like I hacked the matrix when I searched for plus size bras and underwear and then started getting ads on my social media all the time. A constant, daily stream of fat ladies in underwear in my feed. It did so much good for my own self image! Using the algorithm for good!

I was a very tall eighth grade girl-- I hadn't quite hit six feet yet but I was six to eight inches taller than all my friends. This was not cool at the time and believe me no amount of "I wish I were tall like you" will ever erase the daily chorus of 'too tall' from the boys lined up outside the girls locker room before gym class. There is nothing so "flattering" that it will hide that tall. And somehow knowing that gave me the freedom to briefly stop trying for cool. I immediately started "borrowing" my dad's pullovers and flannel shirts. Which were huge on me, but did hide the fact that in addition to being very tall, I had also been recently and decisively mauled by the boob fairy.

Coincidentally it was1994, and grunge was cool, but I didn't really know that (my parents raised me to have an encyclopedic knowledge of NPR commentators and the haziest notion of popular culture).

Which ironically somehow lead to me briefly inspiring a craze in the popular girls for wearing their dad's wool pullovers in earth tones. It was utterly surreal to have several of them sidle up to me and ask where I got the gigantically oversized (my dad is 6'5" and solid) sweaters I wore every day. Mutual incomprehension as I and girls who flew to Seattle to go school shopping both struggled with the realization that I'd accidentally been cool somehow and Nordstrom wasn't involved.

I wish I could claim that this started me on the road to being a proto-influencer and sometime fashion rockstar. It didn't. The popular girls and fashion moved on, and I got taller, and remained bad at dressing myself, but I had learned one indelible lesson, "I can't beat them, I can't join them, but sometimes if I'm are obdurate enough they might join me." And that was helpful for me.

When my partner first described me to his mother he said, "she has clearly realized that she cannot blend in, so she's decided to stand out."