Because I have an odd career path, because I’ve written four books, because I used to be a professor, because I worked for BuzzFeed, because I now write a newsletter and that newsletter is in its third year, because of any or all of those reasons, I get a lot of requests to participate in projects, interviews, podcasts, etc.

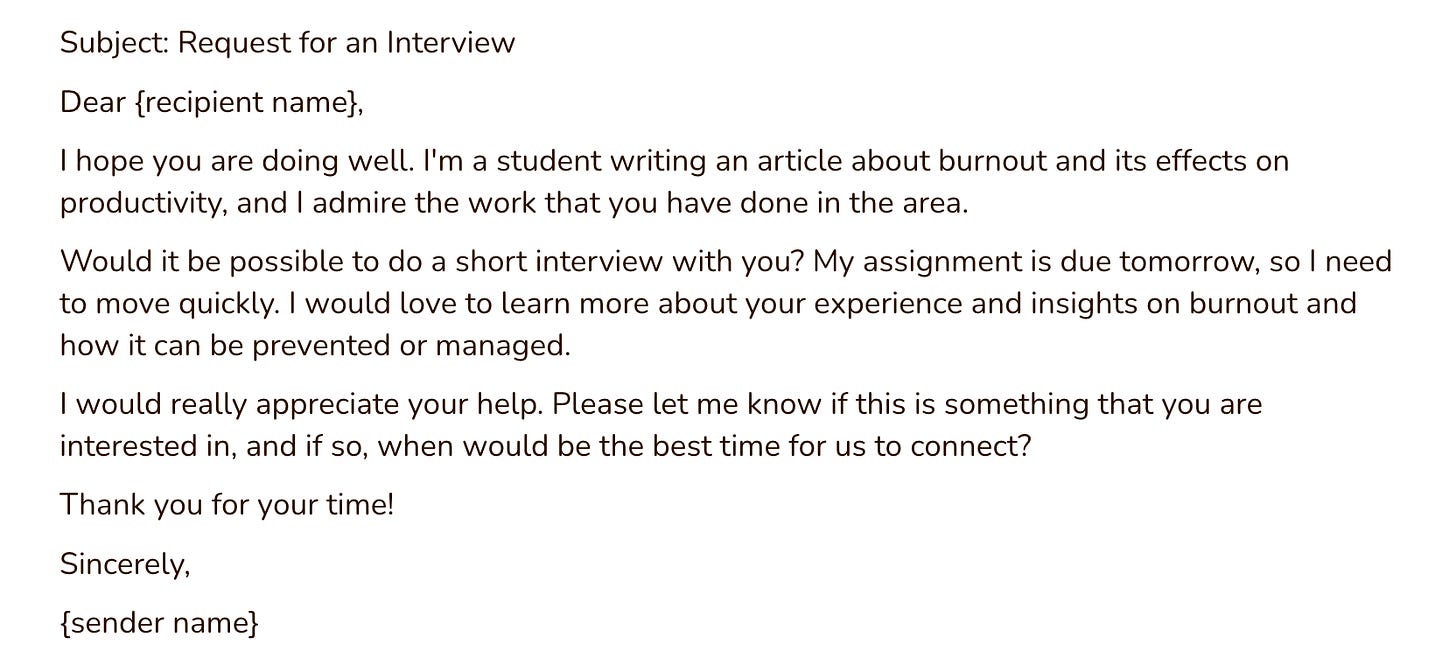

If you’re a journalist, a writer, a community leader, a local celebrity, a podcaster, a CEO, a person who’s spoken at a large or small event, a religious leader, a professor, or anyone with any sort of visibility and/or expertise, you have also been on the receiving end of these emails. Sometimes they come from high school students or undergraduates or recent graduates; sometimes they come from people who just “want to pick your brain” or network. Sometimes the end project is part of an assignment (“find an expert and interview them!”) sometimes the end project is just wanting to know more about how something works. The requests vary. But the emails themselves have something in common: they are almost always very, very bad.

Or, let me rephrase — the emails themselves aren’t “bad,” or malicious, or even necessarily poorly constructed. They’re often quite polite. But they are very bad at doing what they’re supposed to do, which is convincing the recipient to do what you would like them to do. Asking for someone else’s time is an art form, and most inquiry emails are trash.

I say this with full knowledge that I have sent hundreds of trash inquiry emails in my lifetime. I don’t have records of the first ones I sent in undergrad, because that email address and all its memories are long gone. But I can recall so many of the trash inquiries I sent as a graduate student, usually to other academics who’d written an article I found interesting, asking them open-ended questions about journal articles they’d written a full decade ago.

All of those emails went ignored, as they well should have. In a few instances, I found myself meeting the recipient in some capacity some years later, and I’d apologize: “There’s no way you’d remember this, but I sent a truly ridiculous email to you many years ago, asking for you to explain [the connection between Julia Robert’s performance in Erin Brockovich and the rest of her star image].”

They laughed, I laughed, we all laughed because being very bad at this sort of thing has become the status quo. You’re bad at it until you’re good, or maybe you’re just always bad at it and never get better because no one, truly no one, ever teaches you. There’s just the invisible curriculum of how people get other people to give them their time, and it’s your loss (and fault!) if you don’t absorb it.

Across disciplines, we should be teaching “how to write an email asking for someone’s time” the same way that we teach any other building blocks of the field, from grant writing to IRB proposals. And it should start early. But since we aren’t, I thought I’d outline some of the tactics that 1) have proven effective when people email me, asking for my time and 2) some of the tactics I use when I email others, asking for their time. I’ll also share an example of an email that worked really, really well — and the things I see again and again in emails that lead to me declining.

I’ll also open up the comments below for others to offer their field-specific insight and for others to ask questions, because I’d love for this to be a real resource for subscribers. (As always, if you can’t afford a subscription, if you’re on SSI or un- or under-employed or a student, just email me and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked; paid subscribers make this policy possible!)

I’ll start with a cold email that worked really well.