This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

Listen, there are people you encounter, however briefly, and end up living rent-free in your head for years. For me, that’s Brooklyn and Bailey, whose Instagram has become a rich text right at the intersection of Christian youth culture and influencer capitalism.

I first wrote about them last summer, when they caught COVID upon their return to Waco, Texas for their senior year at Baylor University. At that point, I was interested in how influencer life intersected with various institutions’ desire to bring students back on campus — and the difficulty of squaring the reality of COVID with higher ed’s marketing of itself as a lifestyle. (Every lifestyle needs ambassadors — it’s just that some, like NCAA athletes and the people of color recruited to be on the cover of the school magazine, don’t receive monetary compensation, and others, like Brooklyn and Bailey, get “paid partnerships.”)

Since this summer August, a number of influencer things have happened.

They recovered, fairly quickly, from COVID.

Brooklyn’s long distance boyfriend, Brooks, whom she met during a multi-part YouTube dating series that culminated right before B&B contracted COVID, came to visit Waco, and they went to the Magnolia Silos — Chip and Joanna Gaines’ headquarters/mediocre cupcake store — to celebrate.

They added to their clothing line, LashNextDoor (general aesthetic: Modest 1994 at Delia’s price points).

They did sponsored ads for Amazon Prime Student, Smartfood, and The Office, now streaming on Peacock.

Brooklyn broke up with her long distance boyfriend, Brooks.

Bailey and Asa — her boyfriend of four years — posted a lot of prom pose iteration photos.

B & B celebrated their younger sister’s 16th birthday by doing this awkward slow motion video with her (I have watched it at least 45 times and counting).

B &B’s dad, Shaun, kept commenting on every one of their Instagram photos.

B &B’s sister, Rylan, the one in the back of her own birthday video, amassed 322k followers; their other sister Kamri hit 1.6 million, and Asa reached 203k (enough for his own spon for Prime Student and HPSprocket)

B & B entered their last semester at Baylor — but unlike previous years, when their content was filled with on-campus activities, including their experience joining a sorority — campus life, in whatever form, has been secondary. I get it: senioritis must take particular form when you’re not really hanging out with your friends and you have six million Instagram followers.

And then, earlier this week, Asa and Bailey got engaged.

At the Presbyterian college near where I grew up, the college of choice for many members of my church and fellow church camp counselors, there was a women’s dorm on campus known for its engagements. They had sweatshirts (the one I remember was red, c. 2001??) screenprinted with the three tasks residents of this dorm were supposed to complete before graduating:

Accidentally drop their tray in food service

Catch a “virgin” pinecone (aka, catch a pinecone falling from the hundreds of evergreens on campus before it hit the ground)

Get a “Ring by Spring” of their senior year, if not before.

If you think this is weird, well you have obviously not been around college-age Christians desperate to have sex and/or desperate to keep having sex but not feel bad about it! (Brooklyn and Bailey are Latter-Day Saints; they chose to attend Baylor in part because of the school’s evangelical Baptist culture).

When you grow up devout and dedicated to whatever version of purity culture your religion espouses, women in particular spend a lot of time anticipating the hinge moment in their lives: when sex turns from something bad to something good, when their future transforms from unknown to known, when desperation and fear of an uncoupled, child-less future is replaced by certainty and future value. In my experience, these marriages were rarely figured as the culmination of an “M-R-S Degree” — women would still graduate, still find jobs afterwards, at least until they started having kids. As the sweatshirt for that college dorm made clear, engagement was a sort of checklist item to complete: a mission accomplished.

I’m not saying that women in these situations don’t love their future husbands. I’m saying it can feel like a massive relief — which ultimately says less about the specific relationship and more about the way society conceives of women’s sexuality and general value, both in and outside of devout religious communities.

That’s a whole ideological tangle. But it gets distilled, in aesthetically beguiling form, in the proposal. Let’s look at it again.

The design, the clear presence of a photographer, the hand over the mouth — the most common response to this photo, when I posted it on social media, was “there is no way this was a surprise.” No matter how many times you’ve seen them, there’s still a general recoil from attempts, like these, to cloak highly orchestrated moments in surprise and authenticity. While I am admittedly confused about the order of operations with the ring sponsorship (did the ring company reach out and say ‘you look like you’d like to have sex with your longtime girlfriend, do you want to propose using our ring?’) nothing about this seems more or less performative than any number of non-influencer proposals. The point isn’t surprise. It’s performing the dance steps of purity to sexual monogamy, of incompleteness to completeness, of risk to security.

Before you start yelling about how your own proposal was different, that you abhor purity culture, or how marriage is no assurance of security: Friends, I know! We know this! And yet this particular routine, and the norms that guide it, persist — repopularized and reanimated through celebrity performances like this one.

All celebrity images embody ideologies in some way, pinning down fluctuating ideals of what it means to be a mother, a black woman, a teen, a single dad, in a specific moment in time. Oftentimes, these ideologies are deeply contradictory, held together only through the sheer force of a celebrity’s image. Marilyn Monroe’s image was proof positive that women can be sexual and innocent. The same held true, in a slightly different way, for Britney’s image — and both eventually collapsed under the weight of that contradiction.

Influencer images are less complicated than, say, those of the most prominent and popular sex symbols of the 20th century. But they’re still doing a lot. Most are trying (fairly unsuccessfully) to reconcile the classic celebrity paradox of “just like us / nothing like us” (see, for example, Rachel Hollis’s recent rant about “relatability”). Others are about ten to fifteen years fastforwarded in their life from Brooklyn and Bailey, working to embody a brand of domesticity that is at once old-fashioned yet fashionable, conservative but not Trumpy, broadly palatable but somehow unique.

This is no small task, and many influencers have gone through mini-crises over the course of the summer as they tried to figure out how to intersperse conversations about racism and social justice with organizing tips. (Asa, for his part, also struggled with how to acknowledge MLK Day this year). Other influencers grapple with incorporating divorce and single motherhood into their domestic narrative, or how to continue to generate cheery yet subdued content during a global pandemic.

For their part, Brooklyn and Bailey managed to make the transition from Girls with Cute Hairstyles to Young Women Go to College But Stay Cute and Conservative — which includes the sub-narratives of Young Women Have Non-Threatening Boyfriends and Young Women Kinda Cultivate Their Own Style. (Their enormously popular YouTube channel is filled with a style of fun I would describe as classic church lock-in programming; their clothing line is still largely oriented towards teens).

They’ve figured out how to do midriffs without sexiness, how to do relationships that feel platonic. Their image is still, at its core, rooted in cute. The Bailey/Asa proposal works because it hews that line — white teen-style dress, white pearl headband, prom-style flower bower — and naturally builds on the existing image foundation. It also functions as proof positive that amidst all the other representations of teen sexuality and relationships, this sort of trajectory is at once possible and desirable: a fairytale, influencer style.

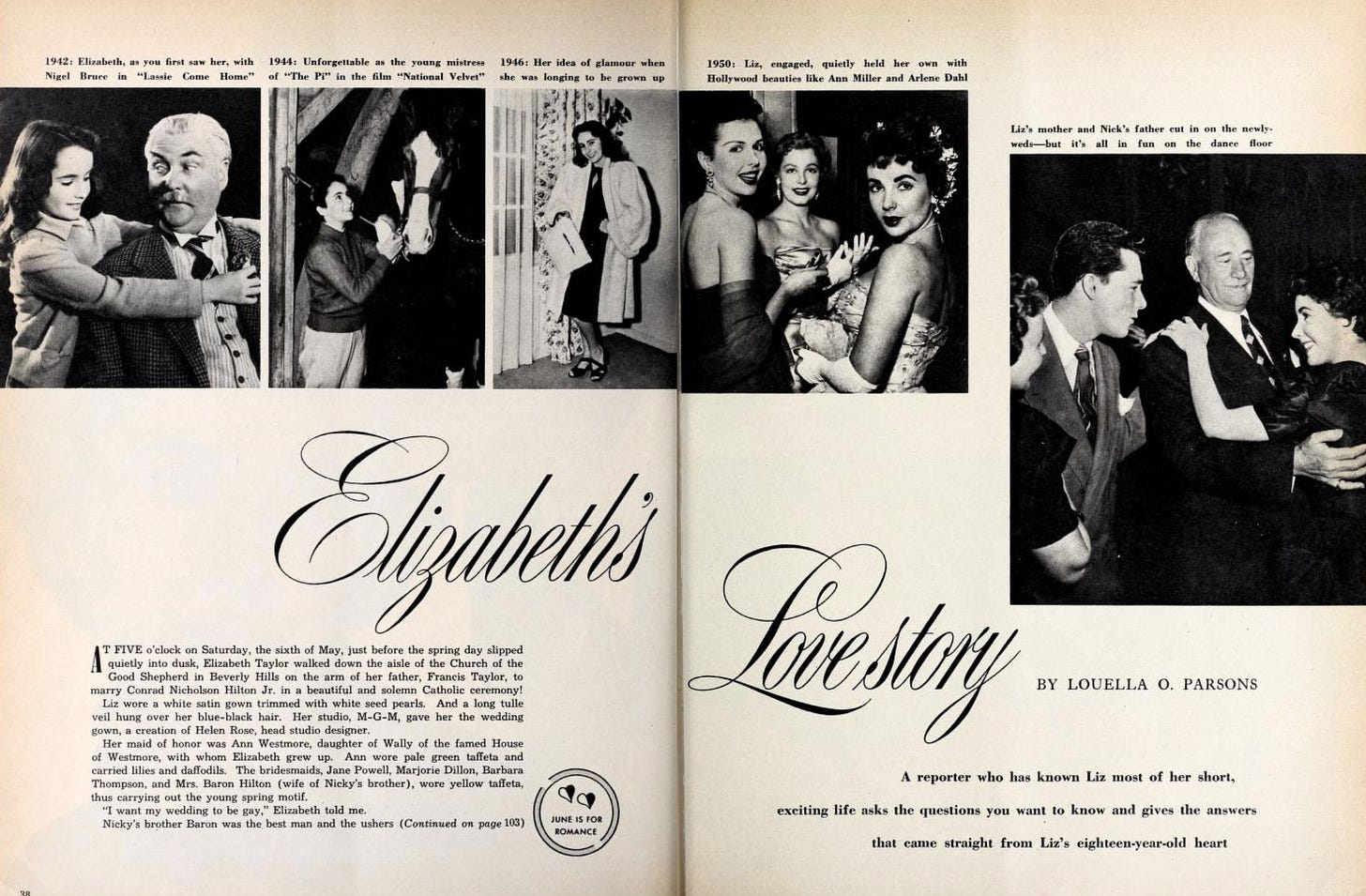

Of course, this is not the first iteration of this fairytale. When she was 18, Elizabeth Taylor’s marriage to Nicky Hilton was framed as a love story for the ages at least until they divorced eight months later. (Hilton was physically abusive and constantly drunk)

MGM used the wedding as part of the publicity campaign for Father of the Bride — and Photoplay used the story above as a totally subtle lead-in to the following:

Later in the 1950s, Debbie Reynolds’ press agents told fan magazines that her mom would embroider ‘NN’ for “Non-Necker” on her sweaters before she went on dates leading up to her very public courtship/eventual marriage to Eddie Fisher.

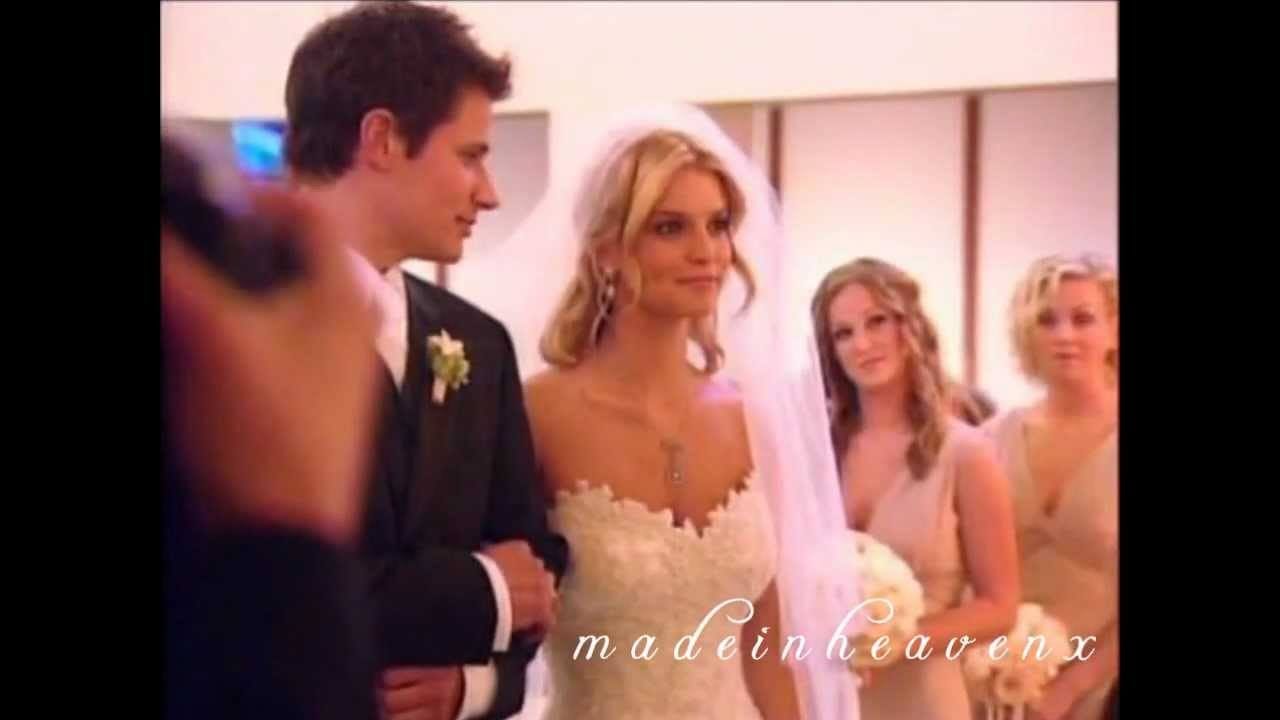

In the 1980s, Prince Charles and Princess Diana’s wedding was, however implicitly, also marketed as a purity fairy tale, and in 2002, Jessica Simpson and Nick Lachey’s purity wedding extravaganza was televised and the lead song off her next album, “Sweetest Sin,” included the lyrics “Can you imagine us making love/The way it would feel the first time that we touch.”

Russell Wilson and Ciara pledged to abstain from sex until their wedding, and then got married at a castle. (Katie Holmes and Tom Cruise: also a castle)

Elizabeth Taylor’s wedding was #spon for her studio, which not only provided the gown, but the publicity, which was simultaneously used to guide millions of viewers towards their own marriage narrative. The same holds true, in however updated a form, for the Bailey/Asa proposal. The pair have cast themselves in the latest public performance of the purity —> marriage morality play, one that we keep watching, keep demanding, keep celebrating, keep commodifying, regardless of how often it falls apart. Because to reject it is ultimately to reject organizing understandings of patriarchal power and control — and would force many to (at least partially!) reimagine how we orient our lives and society at large.

So why do we follow these stories? Some watch to affirm the only understanding of the world they’ve ever imagined. Others follow hoping for the opposite: proof that even the smallest amount of adversity will implode the fairytale and speak truth to the lie. I think I mostly just find attempts to naturalize the objectively bizarre parts of the status quo fascinating, no matter the form. Whatever you think of influencers in general, of Brooklyn and Bailey, or of this proposal, they’re propping up ideological norms. But they wouldn’t be so necessary if the entire enterprise wasn’t so incredibly fragile.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. This week’s Tuesday thread on places you visit again and again is almost as good as getting on a post-COVID plane.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Yes! I have literally been waiting for this since the minute I saw the Insta, and really appreciate the way you offer us context for influencers and how they're really just another form of advertising, with the internet allowing a divorce from the traditional celebrity machine.

A couple weeks ago they did an open Q&A and one of the questions was whether Bailey was engaged...her response was a coy "not yet", and I immediately assumed that there was something in the works, but even in my deep cynicism I didn't go to "sponsored ring".

Also have to assume that the jeweler was involved in the content, given that Bailey is actually wearing a full wedding set in all the photos. It's a very achievable and aspirational look for an outdoor, distanced wedding-and explains why everything is white, where a pink flower sitch would have played up the trendy rose gold of the ring. Interesting to consider the semiotics of this as product advertising separate from the B&B brand building; if it were just Bailey, the focus would have been purely engagement. The presence of a wedding band in the grid photos and, frankly, continuing to be worn in some stories in which the jeweler is tagged raises an eyebrow for me-because why wouldn't they try and double-down on the exposure with a wedding band reveal later on?

I was raised LDS, which meant from about the age of 11 on, every lesson focused on the idea that marriage was not optional. (We were taught that our entrance to the highest level of heaven depended on marriage to a worthy LDS man in the temple, and having children.) My teenage years were a weird blend of being desperately unhappy and depressed, while also feeling bad because being LDS was supposed to make you happy. I really don't miss that culture.