“Identity isn’t a passport into a community”

An interview with author and disability activist Alice Wong

Welcome to Culture Study Takeover Week 2! I love running this newsletter, but I also periodically need to take a small break from running this newsletter. Subscription dollars make it possible for me to pay an excellent rate for someone to curate the newsletter — and give a platform to people with different identities and perspectives than my own. This week, I’m so thrilled to have beloved Culture Study community member Stephanie Sendaula at the helm.

You can find Stephanie’s Sunday essay, on House Plants as a Means of Black Joy and Queer Resistance, here. You can find her Tuesday Subscriber Thread on Comfort Watches here.

And if you value this work, and this platform, and these perspectives, and find yourself opening this newsletter every week — please consider becoming a paid subscribing member. Your contributions make this work sustainable.

I first discovered Alice Wong’s work through the platform that many disabled people use to connect with each other: Twitter. At the time, Alice was just launching her podcast Disability Visibility, and I was both curious and excited about a podcast specifically highlighting the voices of disabled people. I also appreciated how she allowed people who are disabled due to chronic illness, like myself, to have a place to share their experiences.

Over the years, I always looked forward to what Alice had to say on Twitter since she always said what I was thinking. She launched a Disability Visibility Substack a while ago, and I was excited when she announced her first book, Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century, which was published in 2020. I cried while reading chapters that were so true to my own experience that they felt like an inner monologue. Alice’s writing — and the way she used her platform to highlight other disabled people — has always stood out to me as someone who was initially uncomfortable with identifying as disabled and figuring out where I belonged in the community.

Alice’s podcast came to an end last year, but she has been continuing to bring awareness to stories of disabled people, especially ones with intersectional identities. That’s another thing I admire about her: As a fellow woman of color herself, Alice is the first to admit that disability does not affect us all equally. Disabled women of color face both ableim and racism, queer disabled people face ableism and homophoia or transphobia, and queer disabled people of color face all of the above. It’s no wonder so many of us struggle with being unsure where we belong in any community–if we belong at all.

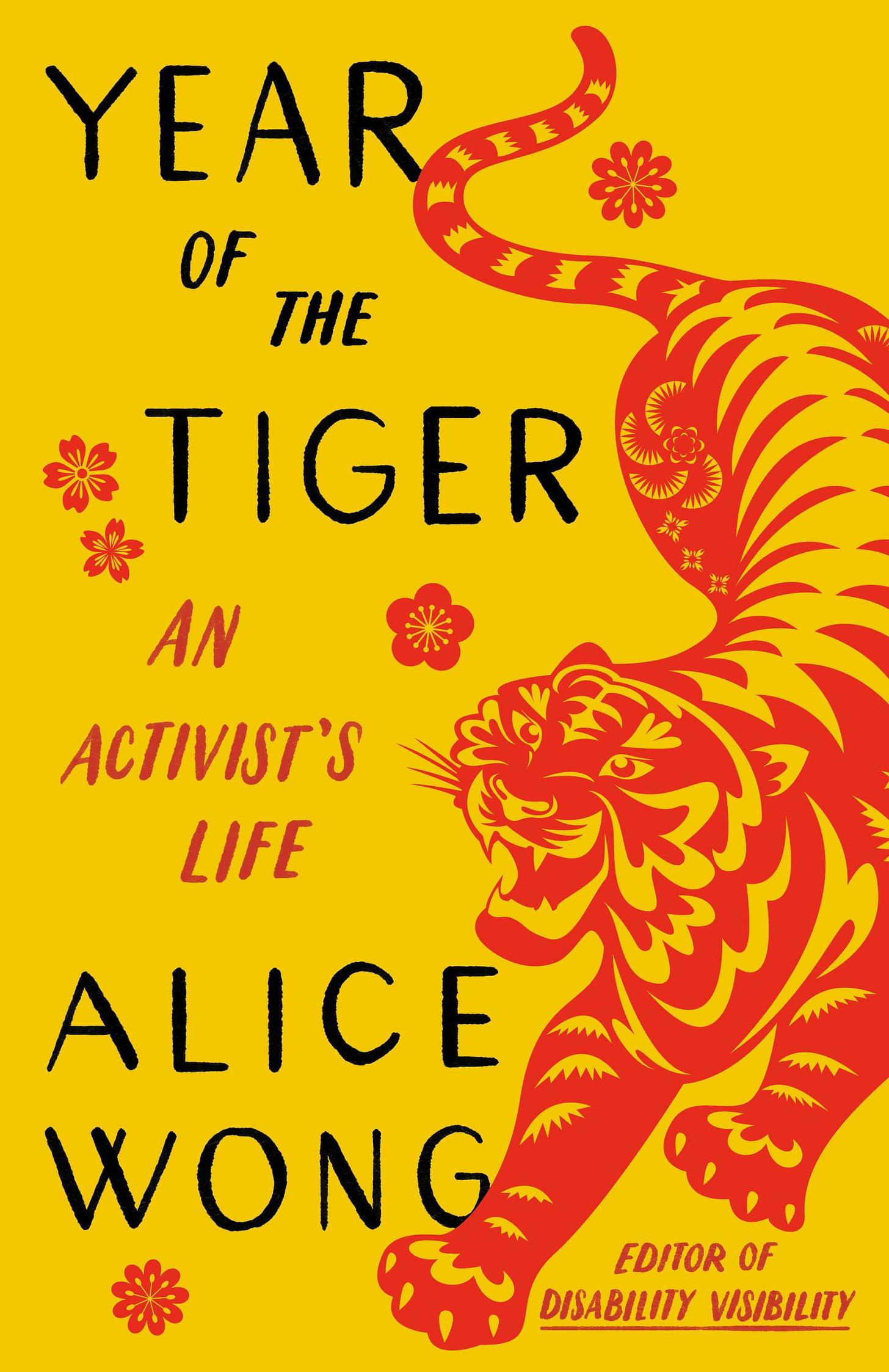

Last year, Alice launched a YA adaptation of Disability Visibility. Most recently, she has been working on an upcoming memoir, Year of the Tiger, which will be published in September 2022. She is also in the process of editing a forthcoming anthology, Disability Intimacy; a follow-up to Disability Visibility. I enjoyed this conversation, which left me thinking about the various places disabled people can connect with each other—whether emotionally, platonically, romantically, and more—and how much further we have to go in ensuring that we are not an afterthought, when it comes to actions and policies.

To start, I want to say that my favorite part about Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century was that it was intersectional in every sense of the word: race, gender, sexuality, class, and more. Could you talk about what led you to put together that collection?

In 2019, an editor at Vintage Books, Catherine Tung (who is now an Associate Editor at Beacon Press), reached out to me about the possibility of editing an anthology. It felt like my whole life led to this moment because I wanted to create one that was rooted in the lived experience featuring the diversity within the disability community. Most disability representation in books and other forms of popular culture is predominantly white. Knowing the amazing brilliance of disabled people of color, and queer, trans, Muslim, and Jewish disabled people, I wanted to present a collection that shows a range of our cultures and communities. I don’t think I used the word ‘intersectional’ in the introduction of Disability Visibility because it just is. It was my hope that the readers see that as the default starting point.

One of my favorite pieces from that collection was "Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time" by Ellen Samuels, and how crip and other terms are being reclaimed by disabled people. How do you feel about disabled people reclaiming these terms, and do you believe it's necessary for us to do so?

The term ‘crip’ resonates with me personally because I consider it as part of my political identity. It originated from a slur then to a term that exclusively referred to physically disabled people to something broader about the power that disabled people have together as a culture. To ‘crip’ something, such as #CripTheVote, a nonpartisan campaign I created with my co-partners Andrew Pulrang and Gregg Beratan, means to transform/reimagine/reframe spaces, institutions, and relationships from our perspectives that are shaped by systemic ableism and other intersecting oppressions. There is also a lot of scholarship in crip theory within disability studies which expands these ideas.

Identity isn’t a passport into a community—if a person doesn’t want to use the word ‘crip’ or ‘disabled’ I still consider them part of the community even if a person doesn’t feel they are disabled ‘enough.’ There is no right way to identify. No one should feel pressure to use terms that aren’t right for them with the understanding that everyone evolves and may go back-and-forth on how they see themselves.

It goes without saying that disability is an extremely isolated experience. Where do you find disabled communities? Personally, I've been relying on Twitter and TikTok over the course of the pandemic.

I love my group text chats, Twitter, and Twitter DMs! I find a lot of comfort now sharing silly GIFs when the world feels so bleak and overwhelming, especially in the last 2+ years. I also have Zoom or Google Meet hangouts with friends, which is nice because I still don’t feel safe to be in large crowds or indoor events. I thought by now, with growing options on how people can connect, that disabled people may feel less isolated — but it’s not true at all. Internalized ableism and inaccessibility keep a lot of people apart, and this is why storytelling and visibility is important: to let folks feel less alone and know that when they are ready, there are communities waiting to welcome them.

Like many disabled people, I often feel like we're being left behind. Each time someone asks, "Do you expect me to be masking forever?" I want to say, "Yes, since I will be." How do you deal with the constant gaslighting? Do you have any advice for disabled people who are feeling exhausted, overlooked, and left-behind?

I am tired too! And for high-risk folks like us, the gaslighting started way before the pandemic, riiiight?!? It’s ridonkulous that it took a pandemic with millions dead globally for people with privilege to slowly acknowledge medical racism and health inequities. The medical industrial complex serves the center. Period. Normalcy is a scam. Period. Ableism is intertwined with ageism, racism, sexism, hypercapitalism, and white supremacy. Period. This is why high-risk people have been treated as disposable during the pandemic and our deaths are considered ‘acceptable losses.’ Eugenics is real and I feel like we, as disabled oracles, have to keep repeating these alarms because in the end our truths are prophecies. And we’re all doomed if we don’t heed them.

High-risk people know the importance of masking and vaccination while recognizing not everyone can do both. High-risk people know that living and surviving COVID-19 may not result in a full recovery. High-risk people know that they can’t rely on the state to get them the help they need, which is why mutual aid has kept so many people alive. I guess my long-winded answer to your question is to use whatever rage you have toward the systems and institutions that abandoned you and throw it into collective care–the relationships you have that help you feel safe and whole. And for those who haven’t found those connections, it’s ok! Ask for help! Keep talking and sharing your truth! Care for yourself, rest, recharge, treat yourself. You deserve it!

I’m using all of my energy to share and publish stories by high-risk people and created a syllabus. People need to know!

As someone who became disabled at a young age, I was also excited to see the YA adaption of Disability Visibility. How did that adaptation come together?

Delacorte Press, an imprint that is part of Penguin Random House (Vintage is another PRH imprint), reached out to me in the fall of 2020 and it was a completely delightful surprise. I wish I had a book like this as a young disabled person and was so thankful for this opportunity to reach younger audiences. I got to write a new introduction for young adult readers and it felt like a letter to myself and all the disabled youth out there who are trying to figure themselves out.

I'm so looking forward to Year of the Tiger — what was your process for writing a memoir?

I had so much fun writing this book and infused it with as much joy and pleasure as possible in the form of art, graphics, photos, and more. Year of the Tiger is divided into seven sections: “Origins,” “Activism,” “Access,” “Culture,” “Storytelling,” “Pandemic,” and “Future.” It is a collection of original essays, previously published work, conversations, graphics, photos, commissioned art by disabled or Asian American artists, and more. I liken it to a mash-up of a scrapbook, museum exhibit, magazine, creative writing assignment, and diary, just without the glitter gel pens or stickers.

I shaped the sections by thinking of what I wanted to share and how to complement the work I already published with new chapters. Originally, I outlined 6-8 new pieces for the book but it ballooned because I realized I had a lot to say, especially as I had time to reflect and make connections with my past, present, and future. The pandemic and other things that happened to me in 2021 also shaped what I wanted to write (that is, all the dumpster fires surrounding us).

As for the process, I tried to think of each chapter as an essay so I don’t feel too intimidated by the task. And then it was a matter of organizing, editing, more editing, and more organizing until the flow feels right. I guess you’ll have to judge for yourself when it comes out this fall!

“Activist” is in the title of your memoir — how do you feel about being called an activist? I've noticed that I've been called one for advocating for disabled people and, on one hand, I supposed that's okay, but on the other hand, we should all be advocating for disabled people.

I wanted a short subtitle to the book so I figured ‘An Activist’s Life’ made sense — even though I contain multitudes and cover other aspects of who I am. It took me a very long time to become comfortable identifying as an activist, even though I have been fighting for myself since birth, and eventually learning about how to leverage that advocacy beyond my own situation. I had to work through a lot of insecurity about who gets to be an activist, what an activist looks like, and what it means to be one. The memoir traces that journey to where I am now claiming that identity and more.

Disabled people have always been community organizers, caregivers, fighters, and activists because we live in the margins of society. I don’t think it’s something that we should glamorize or gloss over because if we lived in a world filled with justice and liberation, we wouldn’t have to work so hard just to live. We could just be. Wouldn’t that be something?

You can follow Alice on Twitter here, and reader her Substack here, and pre-order Year of the Tiger here.

And for more from Stephanie’s Takeover Week: here’s her Tuesday Thread, and her piece on Houseplants as Black Joy and Queer Resistance.

Looking for this week’s Things I Read and Loved? Want to hang out in the threads, or the ability to comment below? Want more well-paid guest interviews like this? Follow through and become a Paid Subscriber!

Subscribing is also how you’ll access the heart of the Culture Study Community. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece (and a whole thread dedicated to Houseplants games), plus equally excellent threads for Career Malaise, Productivity Culture, SNACKS, Job Hunting, Advice, Fat Space, WTF is Crypto, Diet Culture Discourse, Good TikToks, and a lot more.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. Finally, you’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Thanks so much, Alice! I needed to read this today. I have several chronic health issues and the pandemic has been really hard on me. I spent two years avoiding covid - and kept trying to convince myself that I was maybe being too paranoid - only to finally get it this April and to still be sick 25 days later.

The hard thing is not just having privilege as a white woman but also having privilege in that at this point I still have the ability to work full time. It sucks because it doesn't feel like a privilege in a country that doesn't care about even mildly disabled people. I often have to go to work sick and have to be conscientious about trying to bank what little leave time I can. I'm now in the position once again where I have zero leave left and it's only the 11th of the month so I'm at work feeling like garbage and have to pray that I don't get too sick before the 1st, when I earn one more sick day and "vacation" day (because more likely than not that vacation day will be used as a sick day).

Able-bodied people don't get it at all. I didn't get it, either - before my chronic health issues, I maybe used one sick day a year. Pre-covid, I used about 24 a year. Now I have no idea what I'll need with covid - am I going to get this sick every time? Am I even going to fully recover this time?

I love all of this so much! Echoed a lot of what Death Panel host Beatrice Adler-Bolton said in this interview: https://www.lastborninthewilderness.com/episodes/beatrice-adler-bolton

And this feels like it could apply to so much of so many people's lives: "use whatever rage you have toward the systems and institutions that abandoned you and throw it into collective care–the relationships you have that help you feel safe and whole." YES. Thank you.