inside the vault

More plainly put: Pecker runs a scandal and gossip empire. And every gossip publication, whether online or off, scandalous or fawning, TMZ or People Magazine, has a “vault” of information like this: stuff that’s either been tipped to them, photos they’ve purchased and refused to run, interview tape that got quashed, stories they “caught and killed,” e.g. paid money for and then kept out of sight, lest another publication run them. (The American Media vault is even more potentially powerful/damning, because unlike the vast majority of American gossip outlets, AMI pays for stories. People are infinitely more willing to fork over scandal when there’s financial incentive involved).

Sometimes, the contents of a gossip vault, literal or figurative, are low stakes. I’ve heard rumors for years that People Magazine paid tens of thousands of dollars for a photo of Britney Spears reading a copy of Us Weekly. This was the height of the magazine’s feud/competition, in the early 2000s, and Us Weekly would’ve humiliated People with it….so People just bought the rights to the photo and made it impossible.

Historically, a publication like Confidential could be counted on to bury a story (most famously: proof of Rock Hudson’s homosexuality) in exchange for other stories, like this cover story about how another ‘50s heart throb was a juvenile delinquent (that exchange never seemed like much of an “equal” trade to me, but it also put Hudson’s agent, Henry Willson, in debt to Confidential’s editor/publisher Robert Harrison, which was probably more of what Harrison was looking for).

More recently, TMZ leveraged damaging footage of Justin Bieber to get call in, appear, and otherwise grant access/information to TMZ. . . . and last year, when Republican Congressman Jason Chaffetz (Utah) began making inexplicable appearances on the show, some wondered if a similar arrangement was at play. Usually, the answer is WHO KNOWS, at least until someone manages to illuminate the dark mechanics of the deal (it is, in many ways, a form of blackmail) or enough time passes that those involved, either directly or indirectly, tell all.

Alternately, the celebrity seeking protection runs for President, the man facilitating the purchase of that potentially damning material pleads guilty to eight counts of campaign finance violation, and the holder of the keys to that material is granted immunity as he cooperates with a federal investigation.

There’s two things I’ve been thinking about in the wake of these revelations. The first is pretty simple: the vault exists. I mean, of course it exists. Of course! Do you think every gossip publication runs every single scandal that comes their way? Sometimes, they can’t run it for legal reasons: even with our country’s famously loose libel laws, there are some thing that just aren’t worth a threatened legal suit. Then there’s the matter of maintaining relationships with publicists, which, even with scandal rags like The Enquirer, matters. Obviously the Enquirer doesn’t give a shit about keeping things civil with Brad Pitt’s publicist, or the publicists of any of the other major stars who get demolished in total bad faith on the cover of their magazines every week. But Us Weekly, Ok!, Radar? They need content. They need banal mini-exclusives with C-list reality stars. And one very easy way to keep that stream of content coming is to maintain a leveraged relationship: we’ll keep printing photos of you looking sporty on your way back from yoga so long as you keep tipping the photographer.

With the rise of Instagram, Twitter, and other modes of self-promotion, the production of celebrity has become more ostensibly “transparent” than ever. When you’re mediating every part of your day, there’s no way to hide. And everyone else has cameras, so you can’t even think of doing anything scandalous. Or so celebrities, and the publications that cover them, would like the public at large to believe. But the “authentic” celebrity self produced via social media is just another false bottom, the latest way to audiences believe that there’s nothing to know, or want to know, about a celebrity other than what they very deliberately and very slowly reveal.

Put differently, eliding the existence of a vault, or even the need for a vault — that’s the goal of the entire celebrity apparatus, all the way from the celebrity themselves to their publicists and the publications that possess this information. No one will tell you that they think Us Weekly is investigative, fact-checked journalism, but they also don’t want to think of their gossip magazine as willfully manipulative — and, by extension, them willing or unwitting subjects to that manipulation. Of course these vault exists. But of course we all act as if they do not. Yet the revelation of the American Media Trump vault — and Trump’s move to purchase it — makes it impossible to believe in that fiction.

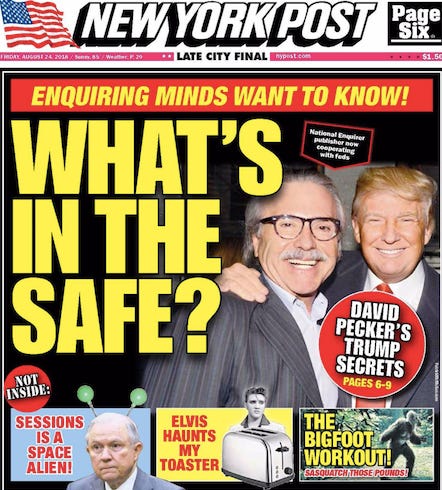

Part of the reason the vault and its contents have remained outside the realm of popular conversation? We sound like conspiracy theorists when and if we talk about it. Look at the cover of the New York Post, modeled to look like the Enquirer: What’s in the safe? The answers jokingly proffered below — Sessions is a Space Alien! — is about how seriously most people take gossip speculation. Take the Pee Tape: total vault material. Is it in the vault? Who the fuck knows. Could it be? The likelihood is not high, but it is also not zero! If you speculate that it might be? You might be Louise Mensch.

TO BE VERY CLEAR, I really dislike Louise Mensch; the frenzied discourse she foments is not helpful. But the aversion to her is part of why people, myself included, don’t want to permit themselves to think that these vaulted materials are real. It’s a slippery slope: believe in the existence of the vault, and then you’ll start imaging what might be secreted within it. (Somewhat secondarily, what’s in that vault that we don’t already know about Trump? What, as many have wondered, would an n-word tape prove that we don’t already about his racial politics? What would a Trump version of the “Ray Ray tape” clarify? Part of the reason the various payoffs to Playboy models haven’t scandalized anyone, let alone his base, is because they’re not revelations: they’re confirmation of what everyone already knew about him.)

This is all to say that when I first profiled the National Enquirer purchase of Us Weekly back in 2017 — and American Media’s coverage of Trump — I knew they had some dirt on Trump they’d chosen not to publish, but I also didn’t think that publishing it would’ve moved the needle enough to change the results of the race. If audio of “grab ‘em by the pussy” played on continuous repeat didn’t alter people’s minds (if, in fact, it actually simply affirmed many of their own misogynistic beliefs) why would a story about watching Shark Tank with Stormy Daniels after consensual sex? Sure, he was married to someone else at the time, but Trump’s hedonism, his vision of the American Dream as making money so as to be able to do anything, truly anything, you want — that’s part of what people responded to in him.

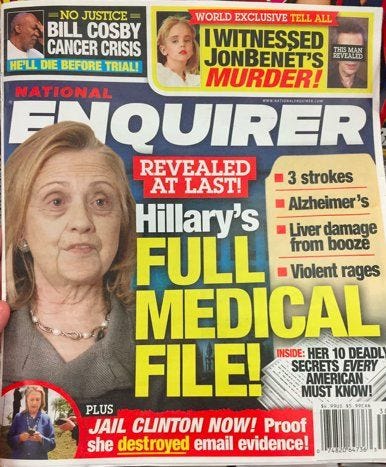

What’s more, I took Enquirer editor-in-chief Dylan Howard’s claims largely at face value. When he told me that the endorsement of Trump — and the fawning coverage — was simply a response to polling his readers (“Never once did he fall below 60% with our readership,” he told me. “He got as high as 80%. So as an editor, I was duty-bound to create content they wanted.”) I believed him. Sure, his boss was pals with Trump. Sure, American Media controlled products had been cultivating and catering to an audience that would not only glom to Trump, but respond to old school tabloid-style trashing of Hillary, exactly the sort of woman who morphs into a nagging, shrill monster on the covers that line the check-out stands at the supermarket.

The Enquirer also give those readers the content they want about Angelina Jolie (she’s a hag!) and what they want about Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood (he totally killed her!) Covering these celebrities in a way that appeases their audience — and subconsciously imprints in the minds of millions who see the covers every week — has undoubted ideological effects. But when it comes to Trump, the calculus is different.

As the Times points out, “at the very least, the material the company had on Mr. Trump would have put its flagship, The Enquirer, in a prime position to dominate on coverage of Mr. Trump’s scandalous past.” Not only that, the explicit and internal endorsement of Trump meant that none of the AMI publications, which often spend the election cycle tearing up both candidates, were effectively devoid of negative coverage. And the scandals they affixed to Clinton in The Enquirer weren’t the almost charmingly misogynistic shit of the decades past, involving imminent divorce, knock-down fights, and general cuckoldry. Instead, they affirmed conspiracy theories — that Clinton was on the verge of death — forwarded by Infowars and Alex Jones. Media critics often single out Fox News as a 21st century version of state television under Trump, but the Enquirer was doing very similar work every week (alleging, for example, that Obama and Clinton ordered illegal wiretaps of Trump, a Trump claim that is simply not true). They were doing it graphically and bombastically and without claim to journalistic integrity. But they were doing it for an audience of millions — millions who might not purchase the magazine, but nonetheless internalize its messages.

At this point, the formalized gossip industry is effectively controlled by AMI. And what it did and did not do with information about Trump is ostensibly no different than what they do and don’t do with information about any number of celebrities on a daily basis. The difference, of course, is that this celebrity became president. And it should’ve changed the way I questioned Dylan Howard and the enterprise he facilitated. It’s no longer sufficient to analysis the gossip industry as, well, an industry. It’s not just, oh, isn’t this interesting, the way the Enquirer mediated information about Trump, the way it produced discourse, the way it ideologically manipulated its readers’ pre-existing beliefs. All those words we use as scholars and analysts feel impotent, insufficient to the task.

I still think, as I wrote almost two years ago, that the key to understanding Trump’s actions is to analyze him as a celebrity, not as a leader or a politician. I don’t think we should stop analyzing or doing investigative reporting or writing opinion or satire. But alone, or at least in their old forms, all of these attempts to understand or speak truth to power when it comes to the president feel, again, insufficient. Which is probably why my initial reaction to requests to analyze Michael Avenatti is nausea: so much of the way he’s been written about, the way he’s been welcomed on national television, suggests how dependent the political system has become on a presence like his, on a mastery of publicity manipulation like his. Which is to say: like Trump’s.

The journalists and thinkers I admire most are the ones who are thinking of new ways to do the work we’ve done in the past. New ways of covering politics, as my own editor-in-chief wrote about this week. News ways of fact-checking. New ways of talking about “lying.” New ways of presenting information and investigative journalism, whether through data or podcasting or breaking down the way a story is reported in an effort at increased transparency around the entire act of journalism. But I don’t think we’ve quite figured out a way to talk about the intersection between celebrity and politics, especially when that intersection includes the darker worlds controlled by the gossip industry.

As someone with a PhD in the history of celebrity gossip who also reports about politics, you’d think I’d at least have some arch suggestions. But as much as I can break down the way that more earnest candidates like Beto O’Rourke or Jon Tester generate aura of authenticity, I feel, at least in this moment, paralyzed in the face of an Avenatti. Which is a real pity: he’s not nearly formidable enough, as a celebrity or a strategist, to merit my fear. If I’m honest with myself, what actually makes me want to crawl into a hole isn’t him. It’s that as we attempt to keep the president accountable through writing and journalism — changing our approaches, our tactics, modifying the paradigms, all of that, as we keep working so damn hard — he’s already dismantled, and will continue to dismantle, the foundations that keep democracy in place. That’s not National Enquirer bombast. That’s just the real, enduring scandal of this administration.

Things I Read and Loved This Week:

Every few weeks or so I just say “trust me on this one.” This is one of them.

My favorite doctor-who-also-writes-on-the-internet takes on the Jordan Peterson all-meat diet

I’ve become so accustomed to this I forgot to be furious about it.

Always read Terese Marie Mailhot.

John Krasinski’s stealth transition to red state action hero

As a commenter on Facebook put it, plainly, “the man is a smoke show.”

This weekend I devoured Ali Smith’s Autumn (a wonderful review of which you can find here). If you are not a fan of stream-of-consciousness or old people, maybe this book is not for you, but wow it was definitely for me. The best endorsement is that when I tweeted about it, AO Scott tweeted back that it was his favorite book of the year. Take his suggestion if not mine.

As always, thank you for reading — the newsletter provides me with the sort of unstructured format where I can work through some inclinations I haven’t quite sorted, and I’m grateful for your patience and interest as I try to do so. That’s also why I ask you to forgive any typos, weird sentences, or blatant evidence that I haven’t tried to polish this into something perfect: it’s what allows me to make the time to do it every week.

If you know someone who’d like this sort of mismash in their life every week-ish, forward it their week or get them to subscribe here. You can also link to it, almost as if it were a blog (it is! it just gets sent to your inbox!) when it shows up here. You can follow my photogenic dog and my reporting trips on Instagram here. And my new newsletter home at Substack is not great (yet) with replies to the actual newsletter, so if you’d like to comment on the newsletter, send it direct: annehelenpetersen@gmail.com. And keep asking for better from everyone in power. It’s the very least we can do.