"It isn’t old fashioned or outmoded. It is vital. It is indispensable."

The incredible import of the state court

AHP Note: Yes, this is a Tuesday — the day for Tuesday subscriber threads. But today is also Election Day. The U.S. Court System is very complicated — and if you’re casting a ballot today, chances are high you’re also voting to retain or elect a local or state judge. In many states that decision could have major and immediate ramifications.

In my former state of Montana, for example, the race between incumbent Justice Ingrid Gustafson and attorney James Brown (a self-professed “constitutional conservative” who was asked to run by current Republican governor Greg Gianforte) has attracted millions in outside spending — because the state Supreme Court will soon be ruling on legal challenges to legislation passed in 2021 that would effectively outlaw almost all abortion in the state. Similarly high-stakes, daily life- and democracy-altering races will be decided today in Illinois, Ohio, North Carolina, and several other states — including Kansas.

I think it’s easy to think of these races as purely partisan — that we should vote for the justice whose politics align most closely with our own. But there’s a very real argument for choosing to retain judges who were picked for their skill and experience interpreting legal precedence — thinking outside the realm of partisan politics. Is that possible? And what happens when the people already appointed are very clearly partisan? What would happen if, say, we were able to also vote to retain or oust sitting Supreme Court justices? What is the value of the appointment/vote hybrid, and what is lost when these races *become* partisan because, well, everything is partisan right now? (Also it varies state by state SO MUCH! If you want to know how it works in your state, this is the most straightforward key).

I don’t have the answers to this quandary, but when Hadley Rolf emailed me pitching an interview with her mom, former Kansas Supreme Court justice Carol Beier, it felt like the sort of interview that could do what the Culture Study community does best: encourage us to think a whole lot more about the systems around us and what sustains or degrade them, particularly today, on Election Day.

If you’ve already voted — amazing.

If you’re in a state where people vote in-person, check-in with any people in your life who have caregiving duties to see if you can watch their kids in the car while they go vote, or bring over dinner so they don’t have to deal with prepping that, too — just say: “is there any way I can make voting easier for you today?” If you have caregiving responsibilities and are feeling harried — don’t be afraid to reach out. People really do want to help. I mean it.

Voting won’t fix our democracy-in-crisis but it is our best defense against its ongoing collapse — and until we actually make voting accessible to all citizens, we need to do our best to make it possible for those in our community.

**If you need a place to talk and spin your wheels while waiting for results to come in, we have a reserved thread on the Culture Study Discord. Paid subscribers, if you haven’t joined yet, just shoot me an email at annehelenpetersen @ gmail and we’ll get you set up.** And if you’d like to subscribe….

And now — here’s Hadley, interviewing former Kansas Supreme Court Justice Carol Beier, inviting us to think more about what it means to sustain the democratic institutions many of us take for granted —

A few weeks ago, we went to visit friends of ours who had recently moved to Albany, New York. Because I am who I am, I wanted to see the Capitol, and as we drove around the building, I asked where the Supreme Court building was. And, even as I was asking the question, I thought maybe I had heard once that the New York state court system used different labels than the federal court system.

“Wait, is the Supreme Court the highest court in New York?”

“No, I think it’s the Second District.”

“Is it the Second District or the Second Circuit?”

“Isn’t that federal?”

“Maybe?”

A quick Google told us that, yes, the Second Circuit is a federal appellate bench, and, also yes, the New York State appellate bench does use different job titles. (The highest court in the state is called the Court of Appeals.)

Everyone in the car had graduated from college. Three of us held advanced degrees. We also pride ourselves on being engaged citizens: we always vote and regularly discuss politics. Yet, here we were. I have lived in New York for most of my adult life and our conversation revealed that I had little knowledge of how our state court system actually worked.

This was especially surprising, given that I am the daughter of a retired Kansas Supreme Court Justice.

My mom, Carol Beier, was a Justice on the Kansas Supreme Court from 2003 until her retirement in 2020. For more than three years before that, she was a Judge on the Kansas Court of Appeals, and, before that, she was a partner at the largest law firm in Kansas.

For the last year, my mom has spent nearly all of her volunteer time working to support her former colleagues on the Kansas appellate courts, many of whom will be on the ballot this year. She has been speaking at events all over the state and raising funds for Keep Kansas Courts Impartial, the organization running the education campaign in favor of judicial retention.

When you are growing up, your parents are your parents. I knew my mom’s work was meaningful, but its full scope was lost on me in the way it’s lost on, I assume, most kids. Now in adulthood, I know how fortunate I am to have had her as my true north.

Our conversation focuses on the Kansas judicial system, but touches on broader themes that regular readers of Culture Study understand as relevant no matter where they live: The need for competent, dedicated local and state officials committed to the common good and the rule of law. The role that all courts — not only the United States Supreme Court –—play in preserving the structure of our government and the resilience of our social fabric. The power and possibility of gender parity. The solace and strength of lasting friendship. And, as you’ll see, “everything that’s important in life.”

Hadley: Thanks for doing this.

Carol: Are you kidding? I love doing this. Talking to you is one of my very favorite things.

Okay, let’s get started. I know state court systems differ from one another — our democratic republic and federalism have room for each state to make its own way on this — can you tell us a little bit about how the state court system is set up in Kansas?

Some brief basics will help. Kansas is like the federal government in that it has three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. It is also like the federal government because, within the judicial branch, there are three levels of courts.

Kansas calls the trial courts “district courts.” There are 105 counties in Kansas divided into 31 judicial districts. The more populous counties with the larger urban areas tend to be single-county districts; the less populous counties are combined with other counties into districts.

In addition to the district courts, Kansas has a 14-member Court of Appeals with statewide jurisdiction and a seven-member Supreme Court, also with statewide jurisdiction.

I served on the Kansas Court of Appeals for about three and a half years, on the Kansas Supreme Court for just over 17 years. Both of those courts handle every kind of case you can imagine. They look to both federal and state law for the rules of decision in the matters before them – whether that law is constitutional, statutory, or “common law,” the term of art for prior judicial decisions. Sometimes you hear the Latin term stare decisis, which means “let the decision stand.” It describes the judicial practice of following prior rulings of our courts and superior courts. The federal courts, and, ultimately, the United States Supreme Court, are the final word on the interpretation of the federal Constitution and statutes. The Kansas Supreme Court is the final word on the interpretation of the state Constitution and statutes.

On the Kansas Supreme Court, deciding cases is what I like to call “Job One.” Naturally, it is the piece of the work that is most important and takes highest priority. But Kansas Supreme Court justices also act as the board of directors for the entire state judicial branch. The Chief Justice is the chair. Together, the justices run a statewide organization with more than 1,600 nonjudicial employees and more than 250 judges who must be responsive and responsible in high-impact circumstances across the 31 diverse judicial districts. This “Job Two” can be extraordinarily complex and delicate, including, as it does, management of relations with the two other branches of Kansas government.

How do people get onto the Kansas bench?

Kansas has three different ways to reach the bench, depending on which court you are talking about.

Under the Kansas Constitution, the process for appointment of Supreme Court justices is merit selection. This means that a Supreme Court Nominating Commission composed of nine persons, five lawyers and four laypersons from throughout the state, accepts applications from interested lawyers; extensively researches all of the sometimes 100-plus-page submissions, including calling all kinds of people likely to know the candidates whether the candidates list those people on their applications or not; interviews the candidates in meetings open to the public; deliberates and votes, usually in multiple rounds, in public; and, finally, narrows the field to three candidates. The three candidates’ names are then sent to the governor. The governor’s staff does additional research, and the Kansas Bureau of Investigation conducts background checks, and the governor interviews the three candidates. The governor then appoints the new justice.

Appointments to the Kansas Court of Appeals are controlled by statute rather than the Kansas Constitution. When I was appointed to that court, the statutory method was exactly the same as the one I just described for the Kansas Supreme Court. During Governor Sam Brownback’s administration, that method was changed to something similar to the federal model with which many are familiar. The governor, like the president in the federal model, can nominate any lawyer who meets very basic qualifications. The governor is free to pursue any method or no method to arrive at the nomination and can conduct this portion of the process with no public oversight. Then, in order to be seated on the court, the nominee must be confirmed by a vote of the Kansas Senate.

Kansas district court judges arrive on the bench by one of two methods, depending on which method the voters in their district have chosen. One is the merit selection process I described for the Kansas Supreme Court, except that the members of the nominating commission come from within the district rather than all parts of the state. The other is direct partisan election, in which judicial candidates declare a party and may campaign in much the same way that competitors in other direct partisan elections campaign.

I am often asked which selection method I favor and why. I am a big proponent of merit selection, which has the greatest potential of the three to insulate the bench from partisan politics. Merit selection was the method that led to my appointment by Republican Governor Bill Graves to the Kansas Court of Appeals and my appointment by Democratic Governor Kathleen Sebelius to the Kansas Supreme Court. I was never asked during either process which party I belonged to or what I thought about any controversial issue already before or likely to come before the courts. We have all watched United States Senate hearings on nominees to the United States Supreme Court; we have all seen the way direct partisan elections are conducted. We know that these processes are infected by the worst of partisan politics, and partisan politics have no place in judicial decisionmaking.

Once judges arrive on the bench in Kansas, how do they keep their jobs?

After one year of service, justices on the Kansas Supreme Court and judges on the Kansas Court of Appeals must sit for retention in the next general election. After that, Kansas Supreme Court members sit every six years, and Kansas Court of Appeals judges sit every four years. District judges’ terms also are four years, and they are subject either to retention election or direct partisan election, depending on the original method of their selection.

Retention elections differ from direct partisan elections because there are no named opponents on the ballot and they are strictly nonpartisan. Voters are asked only, for example, “Shall Carol A. Beier be retained in office?” and they answer either “yes” or “no.” A justice or judge subject to retention must receive 50 percent plus one vote in the election to keep the seat.

Retention elections used to be sleepy affairs. I was up for retention one time on the Court of Appeals and three times on the Supreme Court. During the first couple of retention years, I don’t think I even stayed up late on election night. Voters routinely retained justices and judges with 70 percent to 80 percent saying “yes.”

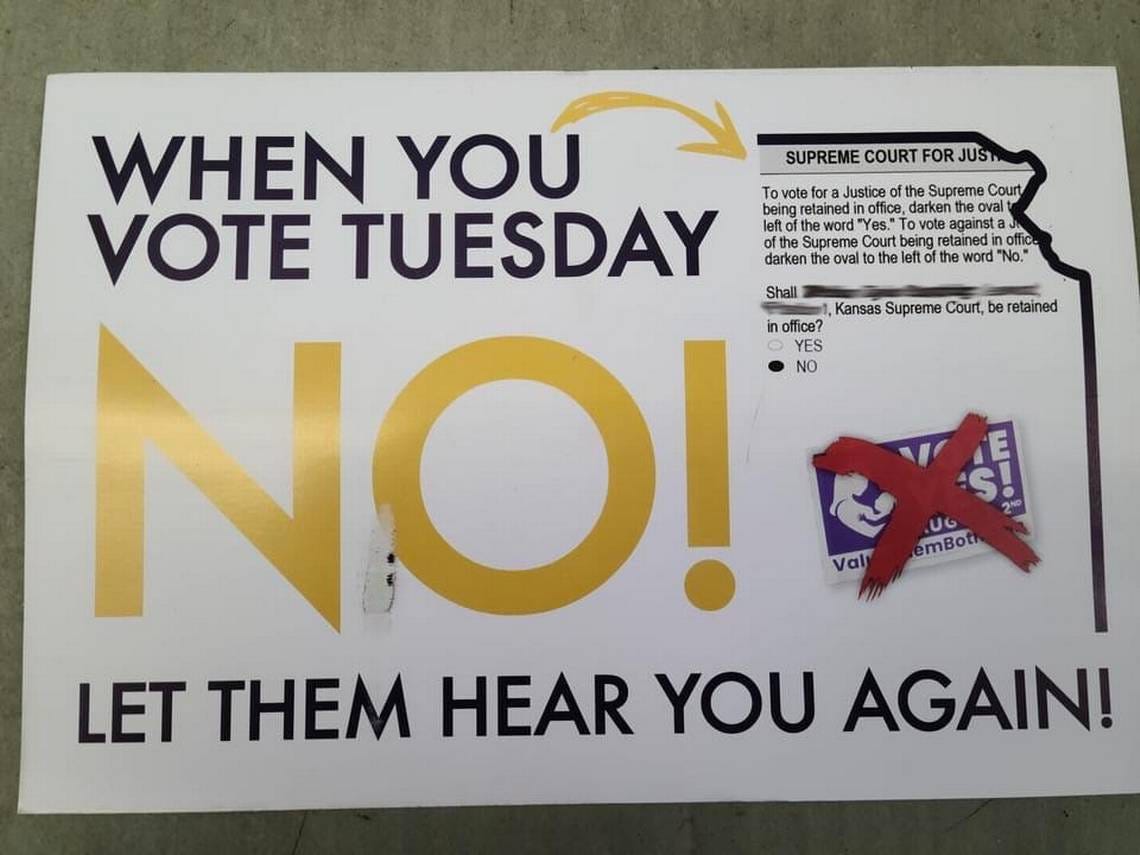

That changed in 2010, because I had written a couple of opinions dealing with the behavior of the Kansas Attorney General at the time, who pursued a strong anti-abortion agenda. His devotees wanted me out, and they launched what turned out to be a rhyming but ineffective campaign to “Fire Beier.” Then, in 2016, four of my colleagues and I were again on the ballot. That year there was an intense, well funded campaign against retention, and supporters of fair, impartial, nonpolitical courts had to rally to our defense. We prevailed, but, by that time, retention percentages generally fell far lower — in the low to mid 50s.

This year we have an even more dangerous historical anomaly. Six of the seven members of the Kansas Supreme Court and half of the members of the Court of Appeals are on the retention ballot.

What difference does any of this make? Why do state high courts *matter*?

They matter because they make decisions about issues that have dramatic impact on the lives of our citizens every single day.

I had a college classmate who was a fellow student journalist, and she was more mature and sophisticated than most of us were at the time. She reported on — and understood and was a part of — “high” culture, played the cello in the university’s orchestra, that sort of thing.

And then, when we all graduated, she got her first job out of J-School at Dance magazine in New York. She stayed in that glamorous job in the big city for several years. And, often, when she was out and about at a swank dinner, the subject of her growing up in a small town in Kansas would arise. When it did, inevitably one of her companions would lean over and ask her, “What do people DO in Kansas?”

My old classmate admits that this question was difficult for her to answer at first. She would mumble something to escape her inquisitor and, eventually, she would laugh along with whatever provincial snobbery the question implied.

It was later, after she had moved back to her home state and married and started a family while continuing her brilliant career at one of Kansas’ flagship papers, when the right answer dawned on her. The right answer was “everything important in life.”

Everything important in life.

When I tell this story, I always get nods of recognition. We all know deep down that this is the right answer. We all want to be able to do the important things in life. Form and nurture families. Launch and grow businesses. Join and lead civic organizations. Be loyal friends. And try, even when it is noisy and nasty, to sponsor and support good government.

That is what state courts like the ones I served on in Kansas are part of: good government. It isn’t old fashioned or outmoded. It is vital. It is indispensable. State courts’ daily impact on the ability of citizens to do everything important in life is vast and deep. The justices and judges who populate those courts must be able to make decisions free from political and economic pressure. They must be free to decide as they were designed to decide — treating all people who come before them as the equals they are.

But, Mom, the pressure when highly controversial issues come before state appellate courts must be intense. How can you operate in that environment? How can judges stick to the fair, impartial, nonpolitical model we all hope for?

State high courts are often called upon to weigh in on some of our society’s most pressing and divisive issues — over the years I was on the appellate courts in Kansas and since, some of those cases have had to do with money for public schools, the death penalty, abortion, voting rights. And the short answer is this: If appellate judges are doing their jobs correctly, they approach high-profile, controversial cases like these in exactly the same way they approach other cases with much lower public visibility.

How does that work? What does “correctly” mean?

Good judges who understand their role consider only three things when they decide cases. These three things compose the entire universe: the issues as framed by the parties and their counsel, the facts as demonstrated to exist by admissible evidence, and the applicable rule of law.

Good judges do not sit around and opine on subjects that have not been brought to their attention. They do not Google to establish the controlling facts. They do not simply decide how they would like a case to come out, or the way the governor who appointed them would like it to come out, or the way a segment of the public, even a powerful segment, would like it to come out. They follow the applicable law to the result. They do not pick a result and work backward to justify it.

Good judges accept that they will sometimes have to vote for outcomes that they personally dislike. They accept that they will sometimes be unpopular with the public.

In contrast, we expect actors in the political branches of our government to make decisions in a very different way. We fairly anticipate, even demand, that they consider public opinion, constituent preferences, voter desires. We expect that they will look to their own values, which they have outlined during their campaigns. We generally want them to reach outcomes consistent with the platforms of their political parties. These branches put the “representative” in “representative democracy.”

I have been reading that public support and respect for the United States Supreme Court is flagging. What is the significance of this for state courts like the ones you served on?

Growing skepticism about whether the United States Supreme Court operates in the way I have described for good judges doing the job correctly is a big problem. Obvious politicization in the selection of justices on the United States Supreme Court and recent casual treatment of some of its earlier decisions have contributed to this skepticism. I am sure there are other factors as well. But we now find ourselves in a place where many of its members are perceived as committed partisans rather than fair and impartial jurists.

This is a very bad place to be. And we need to be vigilant so that the same sort of skepticism does not creep into good government states like Kansas.

There are politicians and single-issue advocates who would like it to. They have been amazingly candid and open about their plan to remake Kansas courts so that justices and judges become tools for the achievement of their policy objectives. They are hoping that the rest of us are ignorant about the true design and purpose of our courts and how our good judges understand and do their jobs. Or maybe they are hoping that the rest of us are just as cynical as they are.

We need to tell them they are wrong. We need to show them with our “yes” votes. We must defend our system of fair, impartial, nonpolitical judicial decision-making so that the rest of us are supported by a viable and respected court system as we continue to pursue everything important in life.

This all makes me really proud of you.

Thanks, sweetheart.

Can we switch gears a bit? We have talked about this before, but can you tell the rest of us a little bit about going to law school and your early practice years — I have heard you say that you were part of the “second wave hitting the beach.”

That is a reference to the second wave of feminism. I was a very fortunate beneficiary.

I started law school in 1982 after a couple of years in the newspaper business. Women had not started attending law school in large numbers until the 1970s, and the profession was still, shall we say, adjusting. Women were not always welcomed cheerfully. I think most women lawyers of my vintage have war stories.

My personal favorite comes from my first few years of practice. I had just begun working on a new civil case, and I called counsel representing another party. I had not previously met this lawyer. When his assistant answered, I said my name and briefly explained the reason for my call. Then I waited a few minutes on hold. When the lawyer picked up, he did not say hello or greet me in any way. He said only, and gruffly, “Which one are you?” I thought he had accidentally picked up the wrong phone line and was continuing some other conversation. I told him my name and the case I was calling about. He said again, and again gruffly, “Yeah, yeah, which one are you?” At that point, I said I did not understand. He then said, “Well, you’re either a bitch or a pushover. Which is it?”

I know there is a great ending to the story. Do tell.

Yes. Fast forward about 20 years. The same lawyer walked into the Kansas Supreme Court chamber to make an appellate argument. And I was sitting there — among my colleagues on the bench. I don’t know whether he remembered our first encounter. But I had not forgotten it.

So how has being a Kansas woman lawyer and judge shifted over time?

There are many, many more women practicing in Kansas and all over the country and the world now. They occupy every corner of the profession. They have power and are adept at using it. I marvel and exult at their growing numbers and the blossoming influence they wield.

When I joined the Court of Appeals in 2000, I was only the fourth woman ever to have served on that court. When I joined the Supreme Court in 2003, I was only the third. The second woman had been elevated from the district bench to the Supreme Court less than a year before I arrived. The first woman had been the only woman since 1977.

The Court of Appeals is now majority female. The Supreme Court has now had six women justices over time. But we still have miles to go to make the courts look like the citizens they serve.

What lessons have you taken from your ability to have a long view of women and their progress in the legal profession and on the bench?

The principal lesson I have taken from my career is that no one does it on her own. Peer support and mentoring are oxygen for the climb – whether we are talking about individual advancement or inclusion and belonging of marginalized groups.

The generations of women lawyers were short when I showed up. Even five or ten years’ difference in law school graduation year made an enormous difference in the options available to you and the number and style of strategies you could employ to advance your own career and, with effort and luck, those of the women on your heels. Intergenerational solidarity was hard to achieve. Some of us failed to appreciate how quickly the landscape was changing. We occasionally forgot that the women ahead of us had to make even larger sacrifices of self than the ones demanded of us. We could be too quick to criticize the women behind us for taking our leadership for granted.

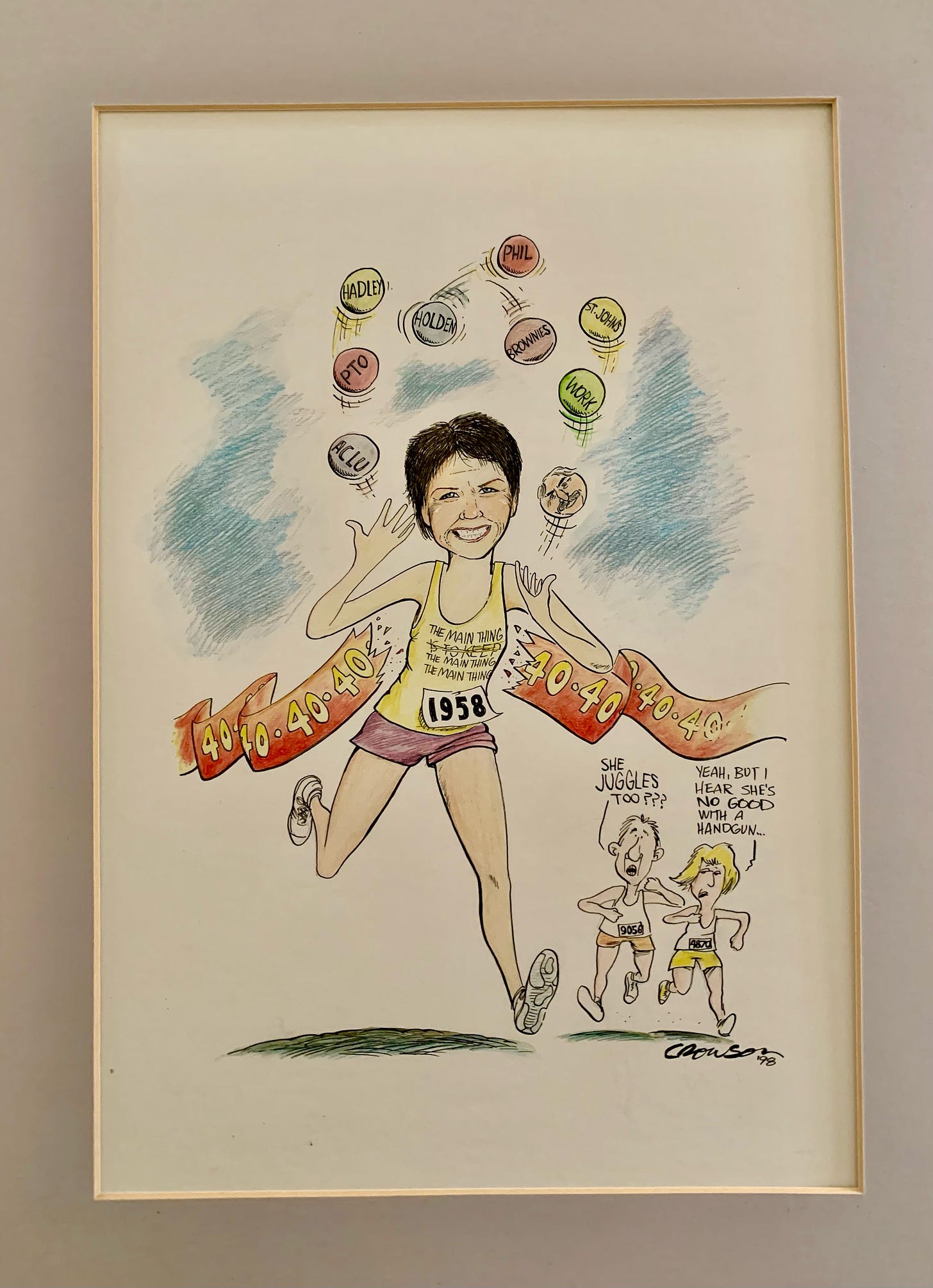

You’ve shared with me before your opinion about the constant refrain that working mothers need to strive for perfect “balance” in their lives. As a working mother now myself, I still hear it all the time. Do you want to talk about the cartoon and all it means for you?

This cartoon is an original drawn by Richard Crowson, then of the Wichita Eagle newspaper.

One of my best friends and fellow lawyer, Gaye Tibbets, commissioned it when I turned 40, more than 24 years ago. I used to be a long distance runner, and it shows me juggling several balls as I break the “40” tape. One of the balls is a mini cartoon of your father; one has your name; there is one with each of your brother’s names. One says “WORK” and others have names or descriptions of other organizations I was involved in at the time. The runners behind me are making a joke about my unfamiliarity with handguns, as though I would be truly dangerous if I had been into those too.

This cartoon hung in my office from the time it was given to me until my retirement. And over the years, the longer I looked at it, the more it resonated on two fronts.

First, although I too have talked about the importance of “work-life balance” many times over the years, I have come to think that balance is the wrong metaphor for many working mothers — at least for this one. Juggling comes closer. If I am honest with myself about my years of working motherhood, I probably only had a genuinely firm grip on one thing at a time. I had to prioritize and trust my sense of what was urgent in each moment, then react to the best of my ability and energy. I did not have some omnipotent talent for balance. And, certainly, any balance I may have achieved during those years was due more to lucky improvisation than to overarching plan.

Second, I should never forget where this cartoon came from and how Gaye and my other closest friends have been there to catch any balls I was about to drop. These friends are family to me. In-and-out-through-the-kitchen-door kind of family. They have a share of the credit for everything good I have ever done or will ever do. I hope they know I know. And I hope all of our children and grandchildren have absorbed something of our model of lifelong loyalty and honesty to each other.

I feel so lucky that we got to have this talk. Thanks, Mom. I love you.

I love you too. ●

About the Interviewer: Hadley Rolf lives in Brooklyn with her husband and five-year-old daughter. When not dreaming about writing the next great American novel, she is doing her best to read them all. While she traded in the prairie for slice pizza and street pretzels more than a decade ago, she still misses Kansas almost every day.

I really love that you didn't edit out the personal bits of this q&a. Really, really love.

This is so beautifully timely. I just voted in Maryland less than two hours ago and cringed when I got to the judges because I completely forgot about them and had done zero research on them. Not that I probably could have done any easy research anyway - it's not like the judges have campaign websites that tell me how they ruled on key cases with evidence that they ruled justly and fairly. If I had seen even a single campaign sign for them, I would have at least remembered they existed.

I voted yes for them both but then started to have regrets. I grew up hearing the saying "when in doubt, vote them out!" and wondered if I should have done that instead, or just left it completely blank because I shouldn't allow my lack of knowledge to sway the election. I considered requesting a new ballot but was worried that if I did that I would be standing there for the next hour trying to decide, so I moved on with my yeses, but I admit that I was/am nervous because I'm not sure if Maryland's judges have become partisan like the US Supreme Court.

I was happy to vote for Question 1 to change the name of the highest court in MD from the MD Court of Appeals to the MD Supreme Court and the second highest court from MD Court of Special Appeals to Appellate Court of MD, because I, too, get confused about which court is which because the names are different, and I've studied urban planning and land development law! But Question 5 threw me for a loop (why am I voting for the qualifications of another county's circuit court judges!? WTF is orphan's court anyway?) so I voted against it.

All of that said, I'm really glad you posted this interview this morning! A lot of it went over my head so I plan to reread it at least a few more times in the coming days so that it sinks in. I think that's why this stuff is so hard - so many folks haven't had civics/government courses since high school and the knowledge disappears.