No One Told Me Being Middle Class Meant Wearing My Retainer Forever

This is the weekend edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing. Subscribers: Be sure to check your email this evening for your invitation to Sidechannel. If you’re curious, read more about it here.

My braces went on when I was in fifth grade. They didn’t come off for nearly three years. I’d go in every month to get them tightened, and would cry from the pain for days afterwards. The brackets rubbed the inside of my mouth raw, no matter how diligently I tried to affix wax. Various metal wires broke free and poked me. I wore rubber bands from the front of my mouth to the molars on each side, and then another rubber band that went across my mouth. I had a metal contraption on the top of my mouth, intended to open up my breathing massages, that would leave deep indents in my tongue when I slept.

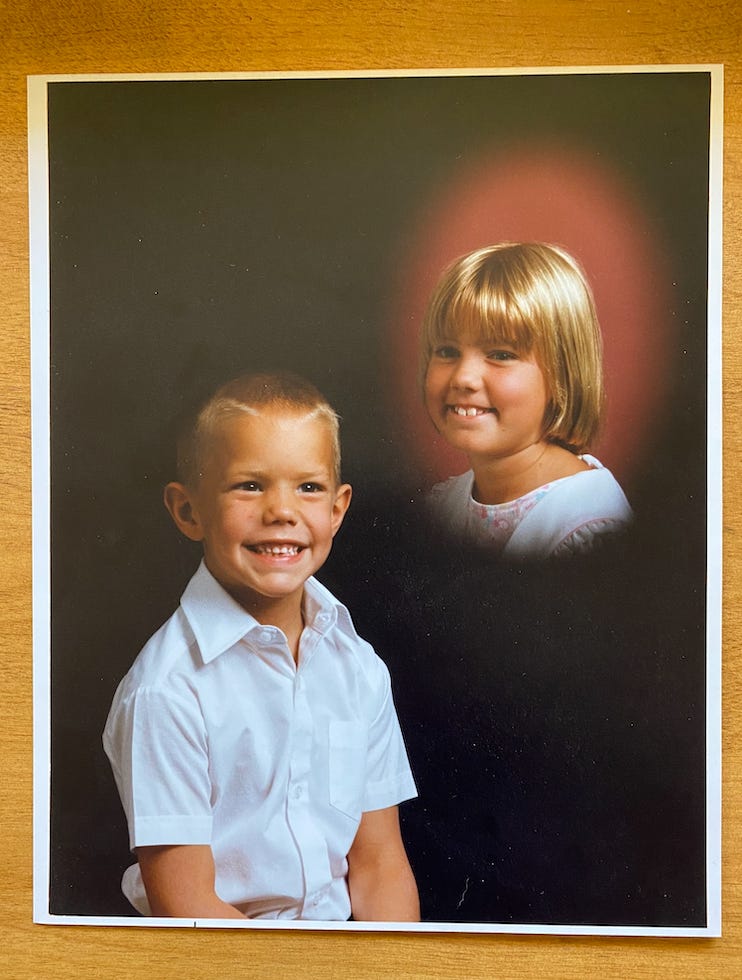

What I’m trying to say is that my parents paid thousands of dollars for me to be tortured by small pieces of metal and rubber in my mouth over the course of three years. I had big protruding buck teeth and a crossbite. It was never a decision, it was a given. Those braces were for my dental health but they were also for my middle-class future.

I was a diligent rule-follower, as braces go, and wore my rubber-bands as much as I could physically stand them. And when the braces came off, I wore the plastic retainer every night, as instructed, cleaning it every few weeks with the same denture cleaner that my grandparents had used. But even that diligence couldn’t keep one of my bottom front teeth from starting to slide behind the other — a trait I share with my brother, my dad, my grandpa, and, I’m sure, some other Norwegians down the line. At this point, I’d been out of my braces for about five years. So they made a new set of retainers, and sent them off with me to college, where, as you might imagine, wearing a plaquey set of plastic every night became less and less appealing.

Looking back, I never even thought to ask the question: how long am I supposed to keep wearing these? Because turns out, the answer is the rest of your life!!!!

When Delia (who’s also part of Sidechannel, subscribe to her media newsletter!) tweeted this the other day, it prompted hundreds of responses from people with metal retainers placed in their mouths as teens for “temporary” support that….just never get removed? Ever? This would be fine, or more fine, if orthodontists were clear about the parameters: here is a thing you will deal with for the rest of your life, kinda like pins in your arm after a particularly bad break, or the filling in your tooth after a cavity. But there’s this weird subterfuge, or maybe it’s a shared delusion, that the work we do, the money we spend, the attention we pay, the pain we endure as part of bourgeois body and class maintenance is temporary.

The reality is much grimmer: for many, “good teeth” means enduring two to three years of misery, then a lifetime of diligent maintenance. Failure to do so means paying some sort of penance: either in the form of another expensive, painful straightening regime, or grappling with the knowledge that your teeth are once again “bad,” which is to say, unseemly in some way, and not indicative of your current or aspired class position.

The best writing on class and teeth is Sarah Smarsh’s “Poor Teeth.” Nothing else comes close. “My family’s distress over our teeth – what food might hurt or save them, whether having them pulled was a mistake – reveals the psychological hell of having poor teeth in a rich, capitalist country,” she writes. “The underprivileged are priced out of the dental-treatment system yet perversely held responsible for their dental condition. It’s a familiar trick in the privatisation-happy US – like, say, underfunding public education and then criticising the institution for struggling. Often, bad teeth are blamed solely on the habits and choices of their owners, and for the poor therein lies an undue shaming.”

Teeth, at least in the United States, function in a similar way that the Calvinists through about work ethic. If you were pre-destined to heaven, your work ethic would come easy: evidence of your elect-ness. If you’re pre-destined for middle class stability, your teeth will either take care of themselves (the allusive, jealousy-inducing ‘good teeth’) or you will do whatever is asked of you to take care of them (retainers, but also going into significant debt for your or your children’s dental work).

My crooked bottom teeth feels like a reminder that class performance can only do so much. Growing up on a dairy farm in Southern Minnesota during The Depression, my grandma’s teeth were pulled, in their entirety, about the time I got my braces off. I’m not ashamed of that tooth, not deeply. But I am enduringly ashamed of the rest of my ‘bad’ teeth, riddled with fillings no matter how diligently I brushed and flossed. A handful of years without dental coverage in my early 20s, pre-Obamacare, made things worse. My dentist currently has me on a ‘crown a year’ plan, replacing one of them every year, spacing out the cost with fingers crossed that one doesn’t shatter ahead of schedule. Crowns are expensive. But they also make the silvery remnants of bad teeth invisible.

Of course, none of this should be shameful, and all of it would be less laden with class baggage if 1) dental care were (rightfully) considered part of medical care; and 2) medical care was considered a right, not a privilege. But that is not the case — and our teeth becomes sites of continual middle class maintenance.

There are other, less medically pertinent sites of continual middle class maintenance. For women in the amorphous life stage before it becomes “acceptable” to have classy gray “woman of a certain age” hair, it’s eliminating evidence of it, often at a significant cost. There’s teeth whitening, and sun spot eliminating, and facial hair waxing, and appropriate moisturizing. Make-up isn’t enough; in fact, too much make-up, particularly on an aging face, is “too much.” Breast implants have to be replaced. Botox has to be refreshed. None of these tasks are one-and-done. They’re monthly, quarterly, yearly costs.

As Barbara Ehrenreich argues in Fear of Falling, the thing we often forget about the middle class is that it requires constant maintenance. Despite the myths we tell ourselves about our country, the poor largely stay poor and the rich almost always stay rich. To maintain middle class status is to be constantly treading water, to be proving and reproving middle class social and financial capital.

Within this scenario, home becomes another site of constant renewal. It’s not enough to decorate according to appropriate tastes in the moment. It’s constantly plotting the next remodel, the next redecoration. Even if you’re on a more limited budget, you can still swap out last year’s tchotchkes for this year’s tchotchkes. Truly wealthy people buy items that are timeless; middle-class people buy items that need to be replaced, either because of poor construction or wear or aesthetic dating, every five to seven years.

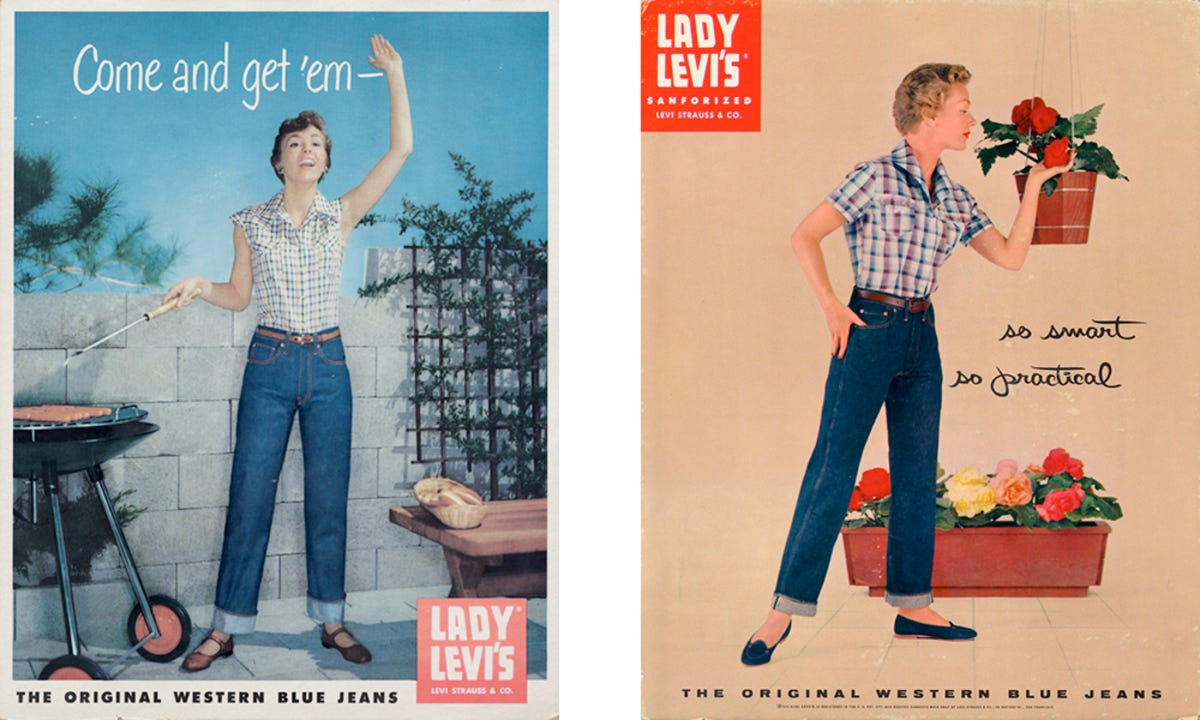

Middle-class clothing is valued for its quality — it shouldn’t look cheap, or worn, or wrinkled — but also for its homogeneity, its clear markers of belonging. Styles and silhouettes travel through middle class acceptability: first introduced as cutting edge, experimental, fashion-forward, slightly terrifying….and then gradually incorporated into the standard middle-class uniform. See especially: skinny jeans, which, over the course of the last decade, have, along with high calf-length boots and an oversized scarf and Pretty Little Liars hair, became ubiquitous. (Its “ideal” form: Christian Girl Autumn).

As Vox’s Rebecca Jennings has rightfully pointed out, back in the mid 2000s, skinny jeans sparked the same anxiety and rejection as straight cut (see below) and flared low-rise do now.

And I sit here in my straight leg jeans that prompted my partner to say that I look like “Diane Lane in an ‘80s movie” (compliment!) and/or that I’m about to go out and farm, I’m reminded of how uncomfortable I felt in skinny jeans for the first time — but also how outmoded my flared low-rise had come to feel. None of this jean discourse is really about fashion, or figuring out what you like. Same, much of the time, when it comes to other forms of bodily discipline, particularly with food and exercise. There’s always a “choice” about what kind of maintenance you want to pursue, but it’s a severely delimited one.

So much of this maintenance is about not falling behind, particularly as a woman. To fall behind is not only to lose a grip on your class status, but your visibility and value within society at large. It’s not just middle class a woman is communicating with “appropriate” clothes and body and grooming. It’s vitality, participation, and gameness in a game in which you’re always already losing.

The pandemic has offered a rare opportunity for people to switch that script. They’ve stopped wearing makeup because they don’t like wearing makeup. They’ve found a body movement repertoire that they like, and, as Tressie McMillan Cottom explains here, are doing it on their terms, because they like it, having discovered what that might feel and look like away from the panopticon of public visibility. (I’ll be writing more about this idea, and Peloton and home exercise in particular, soon).

And yet, we’re also entering into a legitimate botox boom — and there’s a reason that these dumb jeans were one of the first purchases I made after getting my second vaccination. But there’s also a reason that I’m writing about it. The pandemic has made the status quo alien. It has presented “just the way things are” — in everything from the way we work to enduring fantasies of racial equality — on a platter for interrogation.

I’m going to keep these jeans. They’re actually quite comfortable — far more comfortable than the skinny jeans that have left seams in my legs for the last fifteen years. But I’m going to continue to understand them for what they are: one of dozens of ways I try to communicate to the outside world that I belong in the spaces I occupy, that I deserve the things I own, and that I’m still visible, and still have a voice worth listening to. I shouldn’t have to have the right jeans, the right haircut, the right teeth for that to be the case, and neither should anyone else. But most of us, particularly those in places of privilege, in whatever form, are too busy with the quotidian maintenance of that identity to even think about changing it.

Things I Read and Loved This Week:

Rediscovering Cambodia’s lost flavors after war and mayonnaise

A tour de force argument for returning the national parks to the tribes. Just incredible & required reading.

The first piece that’s adequately explained the rise of TERFdom in the UK to this American

A prominent pastor’s son becomes a star of Exvangelical TikTok

This week’s just trust me

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. This week’s Friday Thread was on trying to hold the United States at arms’ length and explain it, and filled with gems and sorrow. The other park: Sidechannel. Read more about it here.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.