This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

Have you ever read a piece of writing — or heard someone on a podcast, or in an interview — and thought, this person, they’re what’s next? As in: they’re part of the group of writers and thinkers that is going to be (my) (our) boss soon, just running circles around us. This might sound maudlin or sad, but I find it invigorating: the next voices, the fresh voices, the alive and important voices, they’re here! What a privilege, what a delight, to have more of these voices — coming from more contexts, more sites of knowledge — every year?

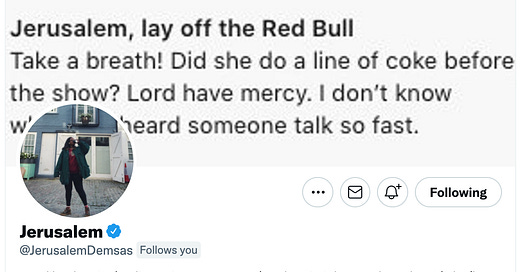

That’s how I felt when I first heard Jerusalem Demsas on Ezra Klein’s podcast earlier this year, talking about (amongst other things) how “blue” cities became so unaffordable for so many, and why so many Democrats are theoretically in favor of infrastructure improvements and affordable housing….but come out howling when it affects their way of life in any way. I’d read a few of her pieces on Vox before that, but the interview (which we talk about more below) convinced me to watch for *every* piece.

And readers, Jerusalem is so fucking good. She’s currently a co-host of The Weeds, Vox’s policy podcast, and regularly writes the sort of accessible, trenchant, policy writing I crave. (Recent favs: “Could Zillow Buy the Neighborhood?,” “In defense of the ‘gentrification building,’” “The economic case for letting in as many refugees as possible”) I wanted to talk to her about her path from college to journalism during the pandemic, how debate helped and hindered her work as a journalist, and what ideas wake up her up in the middle of the night begging to be written.

I think a lot of people look at someone who’s had the sort of success that you’ve had at a relatively young age and either think they’re exceptional or lucky and/or privileged beyond measure, when usually it’s a mix of a whole lot of things. Can you tell us about your path to where you are now? What, in your mind, was a product of chance, of hard work, of connections or practice?

I think no matter how often people say it it’s impossible to appreciate just how much luck goes into where anyone ends up. To give a bit of background, I had been really unhappy in my former professional jobs for quite a bit of time but felt the sort of anxiety I think a lot of people do where — even though you’re only a few years into a career — it feels terrifying to “start over.” Not only do you feel like you’ve put in significant work to get somewhat established in one industry, but other lines of work seem so opaque to you, and all of this is coupled with the gnawing realization (that only privileged and educated young people get to realize this late!) that fundamentally work is a slog and the thing you’re looking for isn’t going to be found in your work.

Covid-19 hit when I was still trying to figure out not even “what do I do?” but “how do I even go about thinking about what I should do?” There were a few animating pieces of advice that I had received from people I trusted: 1) Put yourself in the position to be around as many smart and talented people as possible because the closer you are to people that you admire the more you’ll be able to learn from them 2) Think about the specific tasks you enjoy doing, what roles actually allow you to do those tasks? 3) Identify the worst things about work, what can’t you live with?

I’d also been adjacent to the effective altruism community for several years both from reading Future Perfect and meeting random members of that community, so I’d been trying to align my work with my values around trying to do good in the world.

I could tell you a really nice story about how I optimized all of my preferences and perfectly selected my current career based on my values…

But the reality is that one day I was on Twitter, and I saw that Dylan Matthews had tweeted about a Vox fellowship. I applied to that fellowship and several weeks later, Vox hired me. A few months later they offered me a permanent position, and here I am!

That, I think, gets at how serendipitous this all is. I cannot underscore how unlikely it is that I would have seen the Vox fellowship opportunity if I hadn’t seen Dylan’s tweet. I can’t imagine I would have seen it anywhere else nor was I actively seeking to go into journalism.

Now, once I got to Vox, there was some more luck: First, I had an amazing editor (Caroline Houck) who was willing to let someone who had never before written anything for a media outlet publish a lot of interesting ideas! I don’t know if a lot of other outlets or editors would have given me that kind of a chance. Second, Vox is a relatively small newsroom, and unlike the Times or the Post there weren’t reporters working on every single beat which means there’s a ton of room to explore ideas without stepping on any toes.

I find that I want to stop the story here because it’s very awkward to talk about yourself doing well. You’re bound to be misunderstood whichever way you frame your accomplishments, whether you’re self-effacing to the point of incredulity or confident to the point of arrogance I’ve rarely seen someone walk the line properly, so this is all just me being honest about how I think about things all caveats of course that this is just my perspective and you’re free to think either of those things about me anyways. So, onto what I did to get here, the fundamental thing that I am very good at is taking in a lot of information very quickly, creating or applying different models for understanding that information, and then explaining it to someone else. I attribute my ability to do this to a few things:

1.) I read a lot. English isn’t my first language so when my family immigrated to the United States, I spoke Tigrinya and Amharic. Both of my parents were fluent in English and part of them giving us a crash course to fluency was pushing us to read just as much as possible. When I was young I would just inhale hundreds of books a year. As I’ve grown, I’ve substituted much of my consumption towards articles, tweets, podcasts, audiobooks etc. I do not know if it is possible to learn to write well without having read this much. There are all sorts of courses and articles and whatnot telling people that you can be taught rules of how to write. But writing is like any other skill, if you’ve seen 1000s of the most skilled professionals in your field do something, you’re going to have such a body of knowledge that becomes almost instinctual when you do it yourself. It’s not that Ursula Le Guin or James Baldwin’s writing is somehow reflected in my prose, but that I’ve just seen so many permutations of how a sentence can be structured, of how an idea can be described that it becomes much easier to figure out how to do it on my own.

2.) I was not a policy natural. I write about economic policy a lot. I am not someone to whom econometrics or any type of statistics came easily to. I majored in economics in college but learning economic reasoning wasn’t just intuitive the way it is to a lot of people. What that means is that forcing myself to learn it was an exercise in seeking out the simplest ways that these concepts had been explained and building on that. Often, I have to really drill down what I’m talking to down to the most basic level and rebuild all the way up. In that process, I’m able to come up with analogies or easier descriptions of walking people through more complicated concepts.

3.) College debate. The next question is about this so I’ll just leave my larger thoughts on this somewhat controversial activity for that. But suffice it to say — it was good!

I had read some of your work before I heard you on Ezra Klein’s podcast, but when I heard your voice, I knew almost immediately that you had some experience with debate — when I was a professor, my office was on the same floor as the debate team, so I became very familiar with the particular cadences and structures of speaking. What about your debate background has been particularly useful when it comes to the reporting that you do, and what habits and approaches have you had to leave behind or de-emphasize?

This is so funny to me because I had somehow convinced myself that I didn’t sound like a debate kid but many people have reached out to me to say similar things so… I guess I was wrong!

I think people like to rag on debate for a lot of reasons so I’m just going to leave that to the million thinkpieces that already exist on the subject. For me, debate did a few things.

My freshman year, I had a debate round that was just extremely humiliating. APDA (American Parliamentary Debate Association) is a format where people write their own cases so if you’re on the opposition side you don’t know what the debate round is going to be about until you show up to your round. You have time to ask a few questions but other than that you just get to hear the other team give a speech about their side for seven and a half minutes and then it’s your turn to get up and give an opposing speech.

The team I was up against was very good and they ran a case about whether or not we should patent financial instruments and I remember just being so overwhelmed and unsure. I was too embarrassed to even clarify what a “financial instrument” was. I got up and stammered for just 5 minutes, unsure of what to say or think and just feeling so angry and frustrated by the expectation that I give an 8 minute speech on a topic I knew nothing about.

After the round, a really great debater who had been watching came up to me and said something to the effect of “You should think about the time you have up there as a gift. During those eight minutes, you get to talk, no one gets to interrupt you, and you get to say whatever it is that you think is important. In most of life, that’s not a luxury anyone is afforded.”

It’s an experience that really struck me. So much of thinking through big ideas when you’re young is being embarrassed to ask questions or to give your opinion. Being worried about being mocked makes it hard to talk. Re-orienting my brain to taking up time and space and feeling more comfortable talking was so refreshing. Now that I’m on a podcast, I’m struggling to retain that lesson on such a bigger scale. I’m often talking with people who are so much more well-read, researched and experienced than I am, but the first step to doing that well is just trusting yourself and saying “Now, it’s my turn to talk.”

I got pretty good at debate mostly because I fell in love with being on the opposing side. The side where you have no context and you show up and you have to just figure it out in seven short minutes. There are a few things that I got good at doing here that have translated to my journalism work:

1.) Listening. You cannot be good at debate if you are not listening to what other people are saying. People and sides you disagree with or are forced to argue against.

2.) Building up the best version of the other side. Judges are human and fallible. What that means is to win a debate round you often don’t just have to win based on the arguments made, you have to win based off the best version of the arguments that could have been made since judges will often hear arguments more charitably if they agree with them. Often that means listening to the other side but also doing the work to build the most charitable case for what they’re saying and then tearing it down.

3.) Figuring out what types of people or groups are being ignored. Debate can be boring if everyone is just talking about the same few actors: The government, Democrats or Republicans, etc. Really interesting debates are when debaters are able to think of ways that a policy or idea would affect an unexpected group in an important way. Journalism is like this too.

What’s something that you used to believe pretty strongly — particularly when it comes to policy, or politics, or just the way the world works — that you’ve changed your mind about? What did that process look like?

I just wrote this piece up for Vox so this is a timely question! Rent control is a very touchy subject in the housing world. Economists are almost uniform in their opposition to it and so was I. The economic theory is pretty clear: If you put price controls on housing, people will build less housing, they’ll convert existing rental housing to condos, and landlords will discriminate in a bunch of other ways since they can’t just discriminate based on how much someone can pay.

I was pretty unambiguously on the side of “rent control bad.” But the empirical economics literature on the subject is relatively thin and, especially during the pandemic, it has become clear just how much conventional wisdom in the space changes. The most obvious example is just how much more willing we all got to accept a large amount of fiscal stimulus without worrying that much about inflation.

But also the economic consensus around the minimum wage has become more ambiguous. At one point, the vast majority were opposed but now a growing number believe that the negative effects on employment opportunities are overstated or outweighed by other considerations.

I want to be clear, I think economic theory is super important and useful and nowhere in my piece do I go about “disproving” it. But, I think that it is a tool for understanding the world, not the answer to life, the universe, and everything. That’s why empirical research is so important! Theory comes up against a lot of strange and unpredictable things that exist in real life.

Concurrently working in my head is this big theme in my work, just generally —how impossible we’ve made it not to be a homeowner. The US doesn’t have long term rental contracts that would enable a non-homeowner to stay in their community for a long time. We also don’t have robust eviction prevention laws that would protect tenants from unjust removal from their homes. We also don’t provide the same tax benefits that homeowners get to renters and, simultaneously, local political institutions are designed to care the most about stable voters.

So all of these sorts of thoughts are working their way through my head — and at the same time, rent control policies are passing in a few cities. So instead of writing the standard “Five Reasons Why Economists Hate Rent Control Policies” piece, I challenged myself to write the best case for and case against rent control that I could. And then I ended up convincing myself that (as part of a broader housing policy that is addressing the supply crisis) rent control can play the pivotal role of stabilizing at-risk communities.

What are you obsessed with thinking about right now? Like, what do you wake up and think I WANT TO WRITE ABOUT THIS RIGHT NOW.

This is sort of a half-formed idea that I’ve been noodling on so no one yell at me for missing something (do send me good reading on others who are researching/writing on this though!)

For young, American, urban, college grads, we are living in probably the top one percent of lives that have ever been possible. Access to such a diverse set of cultural experiences, knowledge, art, people, ideas, disposable income…but the politics of this group often presents as so pessimistic and furious. Of course, there are so many things to be angry about, and it’s great if people are animated by empathy for other groups, but it seems unlikely to me that this generation is somehow the most empathetic of all.

This posture is manifesting in an anti-growth politics: so fearful of change, and wary about change and growth. And we see it widely exhibited in urban housing politics, where we often see left and left-of-center groups fighting new housing, but it’s also in people’s attitudes about technology, population growth, and more.

I’m so so intrigued by this and don’t have a full idea yet, but… if I do it will be published!

I sometimes talk about how someone’s work is so good it makes me want to throw the book (or computer) across the room. Who does that for you right now?

So many people! The one that’s really on my mind right now is Amia Srinivasan. I just inhaled her book The Right to Sex, an essay collection about sex and feminism and the politics and power. She’s just one of those people that has mastered writing so clearly but without losing her voice on extremely fraught topics I think many people would shy away from for fear of being misunderstood.

Some others that have been really influential in my thinking over the years include:

I Am A Transwoman. I Am In The Closet. I Am Not Coming Out. written under the pseudonym Jennifer Coates

The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York by Suleiman Osman

Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference by Olúfémi O. Táíwò

What do we owe her now? By Elizabeth Bruenig

Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America by Conor Dougherty

I also feel that people underestimate the benefits of reading fiction, especially speculative fiction which can do so many more fun things with language than other genres. When you see how people build worlds, it helps you think of the ways our own world has been designed and what goes unremarked upon that is actually quite peculiar and important. For that, I have and will always recommend Ursula Le Guin, Ted Chiang, and Kazuo Ishiguro.

You can follow Jerusalem’s work here, and follow her on Twitter here.

Jerusalem is brilliant. Thank you for highlighting her work.

Awesome interview! I've been reading your work for a while, Jerusalem, and I love it! I work in the urban planning field and am passionate about ending homelessness and increasing affordable housing.

Something that has gotten me thinking recently...not only have we made it hard to be a long-term renter in this country, but we also don't make any efforts to convert long-term rentals into homeowners. It blows my mind, for instance, how I have neighbors who rented their townhouse for 26 YEARS and then their landlord sold it to them at a 20% discount. They paid this man's ENTIRE mortgage and their reward was 20% off the asking price. He should have gifted them the house at that point!!!

Even worse, there is a trend in Baltimore City neighborhoods that are ripe for gentrification for the city to buy out landlords of renter occupied houses for $20,000-$30,000 per rowhome to then give the land to developers. Often these renters have been there for DECADES and paid far more than that in rent - why doesn't the city buy the houses and then gift them to the longtime tenants!? Instead, they let the houses go vacant and then gift the land to developers, who either demolish them and then build luxury condos (with a small percentage saved as affordable housing) or rehab them and resell them at 10x the price.

The amount of money that the city also spends in demolishing houses (for empty lots or parks) could also be better used to buy out landlords and gift these houses to the black and brown families living in them. On one block, the city spent $600,000 to demolish 16 rowhomes - that's $37,500 each!!! Yep, the cost of demolition, not even the cost of the real estate! For the occupied ones, they paid between $40,000-$119,000 to buy them out!!

It's mind-blowing that a depopulating city with over 10,000 vacant houses is contributing to making itself less affordable by demolishing existing renter-occupied housing.