If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, if you open it all the time, if you save it for an escape or forward it to friends and family and have conversations about it— consider becoming a paid subscribing member. You make work like this possible.

Back in the late 2000s, I had a Wordpress blog called Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style that I treated as a sort of release valve for all the thoughts and theories I had about celebrity and media that didn’t fit into my academic work. I loved writing that blog, which, not surprisingly, shares a lot of DNA with Culture Study. But the focus, like my academic work at the time, was much, much more celebrity-based. Every few weeks, I’d get bored with grading and take an evening to read every mainstream interview and profile of a celebrity, then do an old-fashioned academic star study of the image that emerged — its themes, its contradictions, how the discourse itself was trying to position the star within the larger ideological tapestry.

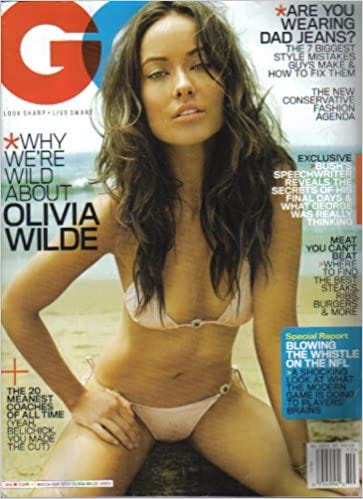

In August 2013, sitting in my backyard in Walla Walla, that’s what I did with Olivia Wilde, who had recently reached that common point in a woman’s Hollywood career when they have to decide if she was going to keep trying to have the core of her image be “hot cool girl,” lean into a sort of cute maternal second act, effectively disappear until they can take unruly roles as older women, or start doing a lot of surprising, provocative, praise-worthy indie work. (I forgot to renew the URL at some point in mid-2010s, but god bless the Wayback Machine for allowing me to rescue the piece itself).

Wilde’s image, at that point, could’ve convincingly been bent in any direction: she had been on the cover of enough men’s magazines and in enough blockbusters to keep going with Hot Barbie, but in interview after interview, she had helped cultivate an aura of cultured, erudite, yet casual intelligence. She’s the daughter of renowned journalists; Christopher Hitchens once babysat her; she went to an exclusive boarding school; she was (for the first decade-ish of her adult life) married to an Italian prince. Her favorite actress is Julie Christie, and when she turned 18, she changed her last name to honor Oscar Wilde. She broke up with the prince and started dating the somewhat bumbling Jason Sudeikis. She was a pin-up, but she was pointedly not that sort of pin-up.

As I wrote at the time, Wilde’s career, c. 2013, was stagnant. She was working like crazy — in 2012 alone, she appeared in Butter, Deadfall, People Like Us, The Words, and The Longest Week, but apart from Butter’s persistent appearance on my Netflix homepage, her work was distinctly below the radar. And not “highbrow art fair” below the radar, but “trying to be good but actually mediocre” below the radar. And therein lies the inherent contradiction of Wilde’s image: for someone with such “good” taste, how did she keep picking such bad roles?

Fastforward nearly a decade. Wilde’s acting career continues to idle, and the string of duds and blips continues: The Lazarus Effect, Love the Coopers, Meadowland, Life Itself, A Vigilante, Richard Jewell. (I actually thought A Vigilante was trying to do something interesting, but the film was never widely released). Much more interesting is Booksmart, which she directs — not a perfect film, but a wonderfully charming one, and enough to get her the momentum to prompt an eighteen-way-bidding war for Wilde to direct Don’t Worry Darling, which had appeared on 2019 Black List, which catalogs the best undeveloped screenplays in Hollywood.

Wilde casts Shia LaBoeuf, Florence Pugh, Gemma Chan, Chris Pine, and herself in major roles; LaBoeuf reveals himself as an asshole yet again and she replaces him with Harry Styles. Wilde and Sudeikis, who have two children together, announce an amicable separation in November 2020 (with the actual separation purportedly happening earlier in the year) and two months later, Wilde and Styles are spotted at a wedding holding hands. Remember, please, that this was in the depths of Covid lockdown, when no one had anything to think about other than how many weeks they had to wait until they could get vaccinated, and this sort of gossip was worth its weight in gold. They keep their relationship consciously low-key and out of the public eye which, of course, makes people even more interested in it. They rarely appear together, but Wilde is repeatedly spotted dancing in the wings of Styles’ concerts.

Sudeikis — who, it’s worth noting, is now firmly associated with his amiable Ted Lasso character — serves Wilde custody papers while she’s on stage for an event promoting Don’t Worry Darling, reviving speculation that Wilde cheated on Sudeikis with Styles. Oh, and Florence Pugh is refusing to promote the film, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear (possibly that her role was reduced, possibly that she didn’t like the relationship between Wilde and Styles?) and early word is that the film itself falls apart.

That’s the backdrop against which Don’t Worry Darling made its premiere at the Venice Film Festival (you can read more, including why people thought Styles had spit on costar Chris Pine at a screening, in this very detailed Vox explainer). Styles and Wilde are still very much together, but note where they stand here (and in other press photography). They’re refusing to provide the image gossip providers want and need to pair with their pieces.

It’s a savvy move, but the spectacle, at this point, might be out of their or anyone’s control. It reminds me of the massive gossip events of the 1950s and ‘60s that eclipsed the actual films the stars were promoting. See: Ingrid Bergman’s Stromboli (directed by her lover/soon-to-be-second-husband Roberto Rossellini), a piece of Italian Neorealism that was marketed to mainstream audiences on the appeal of experiencing the byproduct of a scandal. (Tagline: This is IT!)

Stromboli flopped in mainstream release because, well, it wasn’t a mainstream movie, and certainly not like the major American studio films audiences at that point associated with Bergman. (Bergman also rejected the gossip cycle, refused to repent for actions she never understood as sinful, and spent the next five years in effective exile from Hollywood — but you always got the very real sense that she never liked Hollywood much in the first place, and was happy to tell everyone to fuck right off for a bit. If you want to read more, I always suggest Adrienne McLean’s chapter on her and Rita Hayworth in Headline Hollywood).

See also: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in Cleopatra, a film that became bloated with the truly massive scandal of their fledging affair, captured by the Italian paparazzi and detailed in only slightly delayed detail in the gossip columns, fan magazines, and scandal magazines. The film was a dud, but it was even more of a dud because there’s no way for a middling movie to equal the drama of the discourse that’s accumulated around it.

Olivia Wilde is neither a Bergman nor a Taylor — she’s never had their star wattage, which isn’t her fault, per se, as much as a symptom of the current celebrity ecosystem, which is no longer in the mega star-cultivation business. But Wilde is part of the same celebrity lineage as Angelina Jolie: both exploited the hunger for a certain sort of male-gaze-y pin-up, just about a decade apart, before amassing enough power to lead their careers in a very different direction).

Back in the late 2000s, when Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt may or may not have started a relationship on the set of Mr. and Mrs. Smith while Pitt was still married to Jennifer Aniston, the comparisons to Elizabeth Taylor came naturally. But I’ve also come to understand that Jolie, like Taylor, was always better, and more interesting, in her role as movie star than in her roles in movies. Both of their charismas held up what were often poorly plotted and directed films, in flimsy roles whose primary characterization was usually “is hot.” That’s true of a lot of stars, including Wilde herself, but few have done it quite as persuasively as Jolie and Taylor.

At this point, I find it’s more interesting to think about Taylor and Jolie than it is to actually watch them in a full movie. There are a few notable exceptions, of course (Taylor in Giant, Suddenly Last Summer, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, parts of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; Jolie in Playing by Heart and Girl, Interrupted) and I don’t mean to suggest that either are bad actors, per se. It’s more that the wattage of their stars made it difficult for anyone to see their potential clearly. (It’s not a coincidence that Jolie’s most interesting work was all before she became a global star).

So how does Wilde and Don’t Worry Darling fit into this understanding? Wilde’s been able to direct her career — and, notably, herself, which she does in Don’t Worry Darling — in a way that was never available to Taylor. (I’ve long thought of Taylor’s marriages and divorces as her wielding the one mechanism of control fully available to her, particularly early in her career). Like Jolie, directing has allowed Wilde to bend focus away from her star image and towards her skill. But also like Jolie, there’s something conflicted about that turn. Instead of going full Sarah Polley and rejecting celebritization, both have made decisions in their (public) personal lives that have made it difficult to focus on, well, the work. And I get it, people fall in love with whoever they fall in love with — but falling in love with Brad Pitt, like falling in love with Harry Styles, is a decision with consequences.

But at this point, I think Wilde’s artistic ambitions (again like Jolie’s) are larger than her skill level — which, of course, is something we tolerate and even celebrate in male directors all the damn time. It’s also why I think Don’t Worry Darling itself will be declared a bomb. It doesn’t matter if it’s intermittently promising, or attempting to do something interesting. It’s just not good enough, not even close, to distract from the discourse around it.

It all feels a bit unfair, doesn’t it — that a star can’t just do something without all the baggage of the rest of their career, their star image, their past and present relationships layering upon it. But only white, straight-presenting men have really ever had that privilege in Hollywood — and even then, really only since the dissolution of the star system and the loaded images that accompanied it — to create in a vacuum, to demand to be considered outside their identity, to be able to forge careers for themselves without the need to exploit their personal lives, their bodies, their traumas.

Wilde knows this. As she told Stephen Colbert earlier this week, pointedly dressed down in a simple white t-shirt, [male directors] “are praised for being tyrannical, they can be investigated time and time again, it still doesn’t overtake conversations of their actual talent or about the films themselves. This is something we’ve come to expect. It is just very different standards that are created for women and men in the world at large.” And, as she put it to Vanity Fair just two days after the Venice premiere, “…[we]e worked too hard, and went through too much together, to be derailed by something that really has nothing to do with filmmaking.”

But Wilde also knows she has a film to sell, and she knows how she’s always sold them. Appearing on the cover of Vanity Fair is arguably the most high profile promotion, outside the cover of Vogue, available to a star today, and you can read the extensive accompanying photoshoot as a reflection of all that Wilde is attempting to reconcile with her career, but also in this moment: some of the photos feel almost German Expressionist, her vibe very much The Blue Angel Marlene Dietrich.

Others feel Classic Hollywood glam, a mix of Katharine Hepburn, playful flapper, Dorothy Arzner behind the camera. They make me wonder who Dietrich might have if she could’ve made someone else her muse, instead of being von Sternberg’s; they make me think of all the desire that was sublimated — in costume, in blind items, in double entendres — in the conversations in and around those films. They make me think of the freedoms Wilde has, the possibilities she’s been able to pursue, but also just how resistant Hollywood, and the public at large, remains to their actual in-depth exploration.

Ultimately, these images do little to clarify what’s long felt like the enigma of Wilde, so similar to Taylor and Jolie before her — that ricochet between wanting to be free of a shallow, suffocating system and its norms, but knowing the very best ways to manipulate it. As any longtime Hollywood observer could tell you: it doesn’t matter how well you think you can swim. You can still drown in that shallow water.

ON A VERY DIFFERENT NOTE: I spent a lot of time this summer working on this project, collecting stories of pandemic parenting from over 30 mothers in all sorts of situations, from all over the United States and Canada. They’re transportative and cathartic and weirdly addictive, and their collected form is coming out THIS TUESDAY, September 28th, from Scribd. I’ll write a bit more later this week on the reporting process and what it felt like to really, really listen to people as they attempted to go back and remember the texture of that time, but for now, here’s a link for a free 60-day trial of Scribd (which is pretty awesome, sort of like Audible + eBooks + magazines) so you can have it waiting for you.

ALSO: ARE YOU FLAILING AROUND AT YOUR NEW JOB AND DON’T KNOW HOW TO FIND MENTORS? DID YOU HAVE A REALLY WEIRD ONBOARDING EXPERIENCES? Is your “passion” job slowly grinding you into a fine pulp but you don’t know how to quit because it’s what you always thought you wanted to do? Tell me your work quandaries and they might be featured (and answered!) on a future podcast episode.

Are you ready to join the community? Do you want access to the weekly links and “Just Trust Me?” Do you to be able to comment and be part of the Discord? Well, then:

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus equally excellent threads for Job-Hunting, Reproductive-Justice-Organizing, Moving is the Worst, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Real and Potential Austen-ites, Gardening and Houseplants, Navigating Friendships, Solo Living, Fat Space, Lifting Heavy Things, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

A small correction, with apologies for being That Person! — Wilde’s directorial debut was called Booksmart, not Girlsmart.

I could weirdly - WEIRDLY - talk about Wilde and all of this all day long. I took a break from celeb gossip/watching for about a decade. But this has pulled me back in for many layered reasons. I loved this because it really offered additional context I hadn't seen anywhere else. She feels....very lean in white feminist to me for so many reasons but it is always difficult to know how much is real and how much is perception. I was also just so confused by her interpretation of her own film - the way she presented it as a vehicle championing feminine pleasure in interviews when [spoilers!!!] just totally confused me. But after reading your analysis it kind of...fits in place better now. If that makes sense.