This Friday’s Subscriber-Only Thread is one of my favs in a long time: How Are You Planning For Your Senescence? If you want access to it, plus all past and future threads and the weekly Things I’ve Read & Loved, upgrade your subscription today:

On November 27th, Dr. Ally Louks announced on X that she had successfully defended her thesis in English Literature at Cambridge University: she was “officially PhDone.” Louks posted a picture of herself holding a bound copy of her thesis, embossed with its title: “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose.”

If you’ve ever gone viral on Twitter/X, you know that it usually starts fairly randomly: someone with a large following happens upon your tweet and throws it into their followers’ feed with a quote tweet, usually intended to criticize/lampoon/praise the original poster.

That’s what happened with Louks’ post: it traveled to the part of the internet that 1) thinks academic research is ridiculous and 2) especially thinks academic research is ridiculous when completed by women.

When Louks realized the tweet was gaining a larger audience, she did what any good academic would do: she added context, affixing the abstract of her thesis. In short: she looks at how authors have written about smells over time, and how smell has been used to communicate layered understandings of a person, a place, race and class, etc. etc. Below the abstract, she added: “To be clear, this abstract was written for experts within my discipline and field. It was not written for a lay audience and this is not how I would communicate my ideas to the average person.”

If you have any familiarity with academic research in the humanities, this is not a wild or weird or overly niche subject. It’s just….research. If you’re reading this newsletter, you are in general agreement that there’s always something to be gained by thinking more about the culture that surrounds us. You are in tune with the aims of cultural studies as a discipline. And a thesis like this is part of that project.

But hundreds of thousands of X users are not in tune with those aims — and Louks became the Main Character of the Week on the platform. Her post has been viewed over 100 million times and has attracted more than 11,000 replies. She has received multiple rape and death threats.

Louks told the BBC that she is “unfazed by the vitriol.” In time, her inbox will return to normal, and she’ll be able to joke about the time when simply posting the title of her thesis made millions of people mad.

The vitriol wasn’t really about Louks or her thesis. On X, it’s about finding something — someone — to be mad at, and then directing the firehose of social media in that direction. Her post made her visible; once visible, she became a target. As Ryan Broderick put it in his newsletter, “it’s not really worth analyzing why X users are so angry over something this obscure — it’s likely because there are just not as many normal people to rage at these days — but it is important to use this as an example of why X simply cannot be used as a regular social platform anymore.”

And this, I’d argue, was Louks’ misstep: she posted on X as if it were still the Twitter of, oh, 2019 — when academic twitter was thriving. Intermittently fraught, of course, but what gathering of academics isn’t? It was a place for joy, solidarity, frivolity, and serious debate. Think of that era of academic twitter as an affordable and expandable conference hotel. And now, that hotel has been razed to the ground. In its place: as Broderick puts it: “4Chan with a billionaire owner.”

In other words: the audience will not respond to anything you post in good faith. They will weaponize it against you, and the platform itself will do nothing to protect you. If anything, it will accelerate and amplify the attack.

I understand why so many people stayed on X as long as they did. They despised Musk and what was happening to their community; they saw others leaving….but there still was still some organizational familiarity that made it difficult to do themselves. Since the election, most have given up the ghost and moved to Bluesky in hopes of recreating what was lost.

But the migration is still too diffuse, the excitement muted. Twitter felt like the place back in the late 2000s and early 2010s; now people are trying to decide between Bluesky and Threads and Instagram and Notes and the overwhelming feeling is exhaustion. Some of that exhaustion feels pretty classically millennial: these platforms tell us what to do to succeed (e.g., find our friends, make community) and then keep changing the rules of what it takes to keep that community. It’s not enough to post; you have to post this way (or, god forbid, learn how to make a reel) in order to “succeed.” Fuck that.

But it’s more than just fatigue. People seem to be grappling with a more fundamental question: Does posting add more to my life than it extracts? In this iteration of the internet, in this ideological climate, with these platform-specific incentives — is social media “worth” it?

I used to love posting. I’d think of tweets on walks, then chide myself for thinking of tweets on walks, then tweet them anyway. I craved the immediate reaction, refreshing my browser for likes, keeping a column on Tweetdeck where I could see every tweet anyone posted linking to one of my BuzzFeed stories, even if they hadn’t tagged me. It felt propulsive. It ate my days. It wasn’t healthy but it was the way we did things. I followed people who pissed me off and made me laugh and directed me toward pieces I wouldn’t have found on my own. I understood what people disliked about it — the exhausting discourse, the subtweeting, the performative dunking — and I disliked much of that too. But I never thought seriously of leaving.

I’d give Twitter up for a weekend and come back. I’d delete it on my vacation and hungrily redownload it on the plane ride back. I wanted to see what people were saying — about me, around me. I understood my Twitter following as central to my success. I couldn’t leave; how else would I find new readers? I heard about people who’d deleted their accounts and thought: but how do they know things?

Reading voraciously and expansively, of course — a much more arduous prospect than waking up and logging on. But then Elon Musk followed through on his threat to buy Twitter, and the platform’s utility began to shift. At first, the shift was subtle — everything felt a bit less weird, a bit more angry. There were still daily conversations but the only way to enter them was to amp up the outrage. None of my tweets with links to my newsletter were doing much of anything. My precious verified status increasingly meant nothing. Newsletter writers learned that the apparent burial of our links was not accidental. X wanted us there and only there. Its utility, particularly for someone who used it as a means of promoting their work, had diminished.

That’s the real reason I stopped tweeting in the spring of 2023. It wasn’t some bold moral stance. It no longer made me feel good about myself or others, but that had been true for some time. Now it also didn’t serve me, or what I wanted to do with my writing. I tried Bluesky, but it felt too much like the performative and disciplinary parts of Twitter I’d come to dislike. And Threads, well, the vibes were off.

Everyone, everywhere, was mad; it was too easy to become the accidental target of that anger. And so my posting muscles atrophied. Here’s where I acknowledge that my ability to refuse avenues of self-promotion is the result of my past manipulation of them — and, just to be clear, I’m not telling anyone to leave a platform they feel is serving them.

But I also think there’s something larger going on, particularly with those of us who’ve been posting for most of our adult lives: on Tumblr, on Facebook, on Twitter, on Snapchat, on Instagram. We’re exhausted with the labor of self-documentation — especially when it seems that our posts aren’t even surfacing for our close friends. But we’re also tired of being perceived.

I see the exhaustion in my non-media friends, whose early Facebook and Instagram posting habits have faded into a single seasonal shot of their kids — if that. I see it in various influencers and creators quitting the business entirely. I see it from writers here on Substack, posting on Notes about how much they hate Notes because all they really want from this platform is the ability to write for an audience that wants to read their work, not react to their posts.

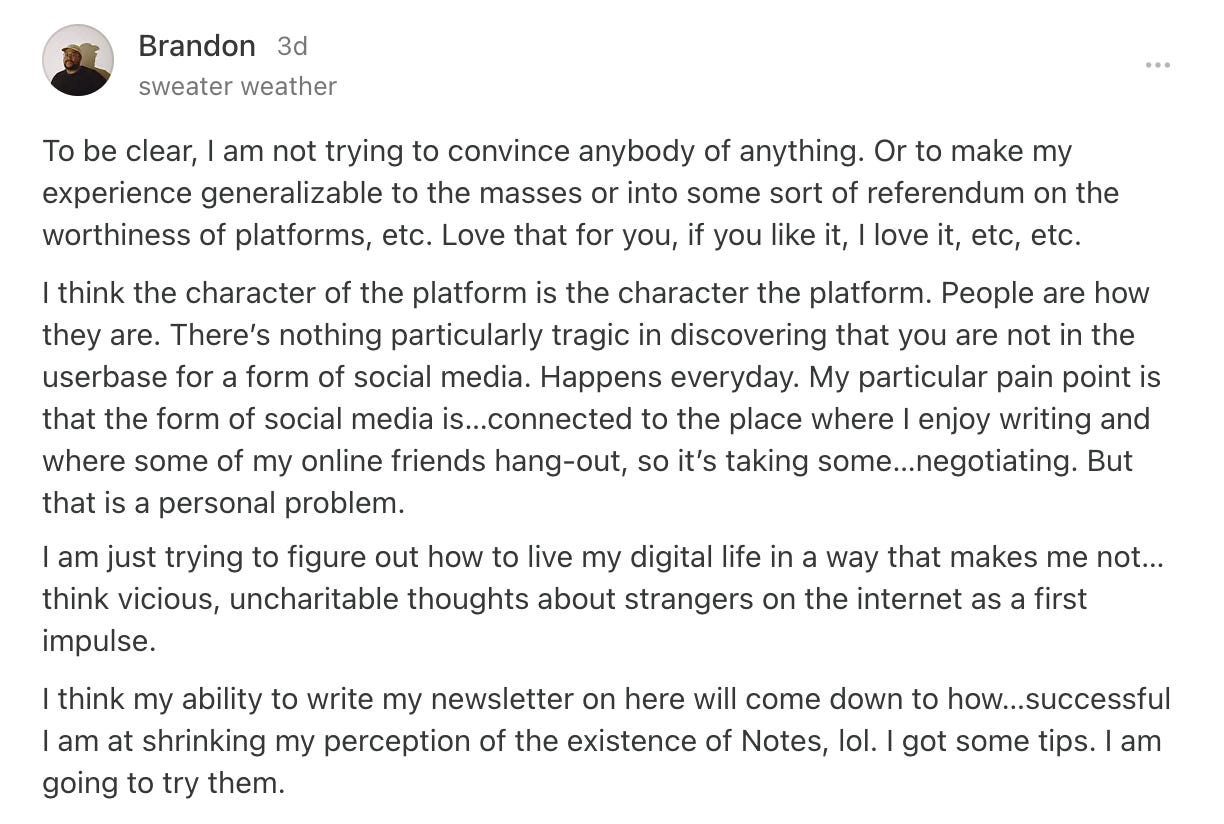

Here’s Brandon Taylor breaking down his antipathy towards Notes:

How do you live a digital life whose primary byproduct isn’t resentment? The most straightforward way: you stop posting. You leave the party.

I started writing on Substack years before the App or Notes, which meant I have no routine with either. There have been times when I’ve chided myself for not engaging more, for not taking advantage of its “growth potential,” but then I realize: the vast majority of people who would follow or subscribe to the newsletter because something went viral on Notes are not the people I am writing for. Through the dark, viral-minded prism of Notes — that’s not how I want to be perceived.

I can feel that understanding spreading to how I make myself available in other spaces. Five years ago, I used to post nearly daily on Instagram; now I post exclusively for major events (my 20 year reunion, a marathon) and for my own desire to periodically scroll back in time with the same pleasure of leafing through a childhood photo album. I post flowers but rarely my home; I post excerpts of my work but rarely myself. It’s a protective impulse, of course: the less of myself I make available, the less available I am for knee-jerk critique — or abuse.

I’m not a snowflake, or whatever pejorative term we’re using to describe someone who still feels things deeply. Along with everyone else in my cohort who’s spent the last 20 years visible on the internet, the most sensitive parts of me melted long ago. I’ve thoroughly internalized The Internet’s gaze, and negotiating with it is exhausting. If you say fuck the haters, the haters are still there, threatening to rape you for your thesis title. Again: It’s far easier to not post at all.

You don’t disappear, you just disappear from full public view. Your Stories only surface to Actual Close Friends. Your cute or weird pics go to the group chat or Marco Polo. Your publics become smaller, more curated. Millennials are reducing their circles this way, but I see younger generations doing it too: their internalization of the internet’s disciplinary logic began at a much younger age than us; they’re either fatigued by it earlier or rejecting it from the start. (I find it telling that Gen Alpha teens often reject their millennial and Gen-X parents’ attempts to document them online — they get it, even when we do not).

In hindsight, the way millennials were incentivized to repeatedly, sincerely share their lives — in the name of connection, for the profit of massive conglomerates — is bonkers. We posted on main CONSTANTLY. We got paid $50 to write about the most traumatic thing that ever happened to us. We thought it was a privilege when Facebook moved outside the Ivies! In the beginning, our thoughts were limited to “friends,” but then “friends” gradually became de facto public. We kept aging, and those friends were still affixed to us.

Case in point: the handful of times I’ve looked to see who’s viewed my Instagram stories, I’ve found the guy who broke contact with my entire friend group back in 2007, watching every. damn. story. He’s just out there passively surveilling my life without posting anything from his own, like a neighbor down the street, always peering out the window with his binoculars, all the blinds firmly closed.

I mean, I get it! Why would this guy post? Straight guys (and straight white guys in particular) are infamous nonposters — they don’t need to be perceived or publicly affirmed to know they’re doing things right, whether as a father or a partner or a businessman.

But if social media doesn’t even provide affirmation — because your grid posts get buried by the algorithm, because your audience has turned hostile — what purpose does it serve? One woman told me that she’s been pregnant for months, and has actively chosen not to post a single thing about it on Instagram. She already has enough voices telling her what to do and what she could do wrong. Why solicit more? Why allow her pregnancy to be perceived — and, as a result, interrogated by half or total strangers?

Kathryn Jezer-Morton has been theorizing and writing about the dynamics of posting for years — it’s at the heart of her own thesis, on “affective expertise” amongst influencers and momfluencers. She’s also currently writing a non-academic book on the topic, The Story of Your Life, and has been interviewing people about their posting habits as part of the process. She told me that a recurrent theme is a fatigue with the style of self-narration that the platforms encourage — which, whether we realize it or not, has been heavily influenced by brand storytelling logics. We talk about ourselves like we’re products.

“It’s created standards for what a celebration is supposed to look like, how ‘fun’ is supposed to be expressed,” Jezer-Morton says. “The logic of telling a brand story has become how people think about themselves. Even people who don’t post much say this, because it’s how they see their friends communicating.”

Some people don’t think about these dynamics at all. It’s just the way things are. But stare at them long enough, and they start to feel uncanny. People start to pull back, even if they don’t realize they’re doing so. When I asked my Instagram followers if they were posting less, I was overwhelmed with hundreds of responses. Some could articulate the reasons (I’m tired, there’s no way to say the right thing, it’s not fun here) but others were perceiving the dynamic for the first time: I just realized I *am* posting way less; I wonder why?

There’s alienation from the now-standard style of self-narrativization, but there’s also a wariness about integrating politics — of any kind — into that flow. You become a natural target for others’ unprocessed guilt, ambivalence, and confusion. As one woman put it to me in a DM, “I feel removed from the desire to share things with people who don’t really know me and have them project their feelings about whatever I’m sharing onto me.” This, precisely.

If you’ve posted on Instagram about politics, you’re familiar with its impossible contradictions: posting something is wrong, but so is posting nothing. Posting with your own words is wrong, but so is reposting something without your own words. Posting while acknowledging your power is annoying, but posting without it is oblivious. You should center other voices but you shouldn’t do it cloyingly. Silence makes you complicit but also: shut the fuck up.

Of course, some of this frustration is just people with societal privilege bewildered that they can’t post their way out of their guilt — and getting uncomfortable with the feeling of having fucked things up, in both the past and present tense. I know this; I’ve been there. But you can also see how this disciplinary logic trickles down, discouraging people not just from posting about politics, but anything about their personal lives. The juxtaposition of others’ politics and a cute picture of your baby or your weekend girl’s weekend is just too much. You can’t be accused of being tone deaf if you’re not speaking.

Back in the 2010s, if you read something online — a meme, a tweet, a listicle, an essay — that resonated with you in some way, you’d say I feel seen. As in: this essay makes me feel seen. It was the perfect phrase for a particular internet era, when we rummaged around the social web for artifacts that would replace our atrophying connections with others. These artifacts were never quite satisfying, and the lack prompted us to share even more of ourselves online, in the hopes of feeling seen more fully.

Feeling seen offered some form of intimacy — but it always turned out to be too broad, sneakily hollow, and almost always commodified. You knew it, even as you recruited it, again and again. You tricked another BuzzFeed quiz, you posted a picture of your brother on National Siblings Day, you tweeted a line from an essay with and captioned it “SAME.” It felt good, like you were extending yourself into the world, making connections, responding, retweeting, liking — and then it felt like nothing.

There’s a difference, of course, between feeling seen and being seen. One happens almost exclusively online, and, at least in the beginning, offered a semblance of control. You picked the photo, you edited the caption, you controlled the audience — you shaped the narrative. You felt others’ eyes on you, liking you, retweeting you, commenting. People saw you, or rather, they saw a story of you. Holding their gaze offered a sense of power, even pleasure. But it was not the same as joy, or intimacy — or friendship.

Being seen is largely impossible online. It involves more vulnerability and significantly more reward. It requires unedited time, a tolerance for awkwardness, profound patience, and presence. There is no algorithm to trick. There’s no way to lurk. It seems obvious to the point of ridiculousness, but it’s true: to be seen, you have to be willing to make yourself a very different sort of visible. ●

If you find this work valuable, if it helped you process your own feelings about social media, if it challenged you in some way — and you want to keep the paywall off essays like this one — consider subscribing:

You’ll get access to the vibrant comment section, the weekly Things I Read and Loved, and the twice-weekly threads (one for media recommendations, the other for more existential life questions, like What Do You Wish People Were More Curious About? and Actual Life Skills….plus the knowledge that you’re supporting the work you find valuable. Subscribe now, and join the conversation.