Screaming on the Inside

"So many of these ideas are just so deeply embedded for us, they’re subterranean."

Have you been meaning to subscribe and keep telling yourself you’ll do it the next time you’re at your computer or near your wallet or or or….I get it, I absolutely get it. But if you have the means, consider paying for the things that have become important to you. (If you don’t have the means, as always, you can just email me and I’ll comp you, no questions asked). Subscriptions make work like this possible.

I have this vivid memory of talking on the phone to Jess Grose — who writes about parenting and more for the New York Times — sometime in the summer of 2021. She was trying to figure out how to structure her short book leave, and how to conceive of the in-depth research on the history of “ideal” motherhood, and sort through the potential interviewees for the book. We were ostensibly talking about strategy (do your research for each chapter THEN WRITE? do all your research THEN WRITE THE ENTIRE BOOK?) but like so many conversations with parents in 2021, we ended up talking about childcare.

As in: there was none, and the only way Jess was able to take the time to write her book was moving in, temporarily, with her parents, who effectively became secondary parents to her two elementary-age daughters. The fact that her parents were alive, able and willing to care, and in proximity — that’s what made this book possible, and, even more broadly, helped make parenting sustainable.

What I appreciated about that conversation — and every conversation with Jess — is how frank she was about the situation. She was grateful, but she was also really fucking pissed about it. Because we can acknowledge that the nuclear family is scam while also acknowledging that you shouldn’t have to be lucky enough to have parents who can provide free childcare in order to not feel like you’re drowning every day. Access to reliable and affordable childcare should have nothing to do with luck.

We also talked a lot about what it felt like when Jess was so sick in her first pregnancy that she had to quit her brand new fancy job — and how that process, as horrible as it was at the time, allowed her to distance herself from any aspirations of a perfect pregnancy, a perfect childbirth, a perfect parenting experience, a perfect return to work. But she saw the grip they had on so many parents — even as they attempted to navigate the pandemic!! — and how the gap between the lived experience and the ideal was only making parents (and mothers in particular) more miserable.

I knew Jess was going to write a bracing, infuriating book. But it’s a weirdly comforting one, too. Jess isn’t a sociologist, but the book itself is sociologically rooted, and functions as a form of ungaslighting: underlining, again and again, that the problem is not the individual’s, but the way we have organized society…the way, as Jess puts it below, that so many of these expectations of “good” motherhood are so thoroughly embedded as to feel unquestionable. But parenting doesn’t have to feel this way. It doesn’t have to be this treacherous, the expectations don’t have to be this confusing, the ideals this unattainable, the feeling of failure so omnipresent. It’s essential for all of us, whether we’re parents or not, to keep underlining as much — and Jess’s work gives us the tools to do so, both for ourselves and for each other.

You can find Jess Grose on Instagram here and buy Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood here.

People often ask me how and why I care about parenthood so much when I’m not a parent, and my sort of pat answer is that parents make up a very high percentage of our society, so how we think about parenthood, the societal posture or hostility towards parenting, all of it has very real consequences on the way all of us live our lives, regardless of whether or not we, as individuals, are parents ourselves. This is a meandering why of asking how you found yourself, for lack of a better phrase, on the parenting beat — and how it is or isn’t different from the path you imagined for yourself as a writer and thinker.

My response will be meandering as well, because ending up on the parenting beat was not my plan (though, in a field as wild and wooly as journalism in the 21st century it is very hard to plan). I mostly worked in women’s media through my 20s, and did cover some parenting stories at that time. Then, I made a conscious choice to move away from it right before I got pregnant with my older daughter. I had this notion, which was part internalized sexism, and part the truth of our industry, that I would be put in a box as a “lady journalist” if I didn’t try to do something else. Even though issues that get categorized as “women’s issues” — paid leave, abortion, child care, etc. — are truly everyone issues, as you say, they are often treated as an unserious sideshow.

But then as detailed in my book, I found out I was pregnant two days into a job on the culture beat, and I immediately got very sick with hyperemesis (extreme vomiting), and then, I also got extremely depressed and anxious. I will never know if that is because I went off antidepressants to conceive, or if it is because I was only keeping down like one clementine every two days. But either way I was a complete mess, and I ended up having to quit that job two months in. At the time, I assumed my career was over, because I was confirming every terrible stereotype people have about pregnant workers.

I took a few months after quitting to just rest. I was still throwing up all the time, but without the added stress of having to be at a job, it was easier. I want to make it clear I was only able to quit that job and have a less stressful time because my husband had a good job with health insurance coverage and we didn’t have any debt. I had basically every privilege an American mom could have and it was still such a difficult time.

After my older daughter was born, I got back into freelancing full time. It was really a wonderful way to ease into motherhood. I worked flexibility, but 30ish hours a week. I was able to build my career back up while still getting to spend a lot of time with my kid and making enough to offset the cost of our wonderful nanny Shelly. I wrote for anyone who would pay me: a lot of business publications, some women’s magazines, really anyone. Would your check cash? I would write for you! I gave myself a day rate that I was aiming for, that worked for us financially and I would take on as much work as I needed to in order to reach that day rate.

Then, we decided to have a second kid. Sometimes I am still shocked that we did, because my first pregnancy was so hard, but I just loved being a mom so much and I don’t think those kinds of decisions are strictly rational. However, what WAS rational was knowing that if we wanted to stay in New York City i would need to go back to a staff job in order to afford a second kid. That’s when I became editor of Lenny, and went back into women’s media full time. I learned so much about journalism startups and management there.

When I saw the job listed at the Times — they were starting a new parenting product at the time — it just seemed to list all of my skills. I had management experience, I had newsletter/new product experience, I knew the topic area very well because I had written about so much of it and lived so much of it. I got that job in 2018, and then, a lot of stuff happened, including a global pandemic which made many, many more people realize that the way we do American parenting is not working for a LOT of people.

Those of us who have been covering it for years already knew that, but I’m glad that more people are talking about it now, and it certainly galvanized a decade of my own thinking into a book.

Whenever I write about a topic, my impulse is always to historicize and contextualize — how did we get there, how did the ideologies that guide us and become so commonplace as to disappear first develop, how did we punish and ostracize and forcefully exterminate those who refused to conform. Why did that process feel particularly important when it came to unpacking American Motherhood? And what part of that discovery process was the most illuminating for you, or just clicked some norm into place, like OHHHH, THAT’S WHY WE DO THIS.

My book is chronological, in that it loosely follows my motherhood experience. So, the first question I wanted to answer historically is: Why do we even expect to feel good during pregnancy? Why is that pressure to glow and exude happiness even a thing in the first place? Many people don’t feel that good! I have known a lot of pregnant women in my day and I would say maybe 5 percent of them feel better than usual, and medically speaking there’s just a whole list of maladies — gestational diabetes, for example — that you don’t get at other times in your reproductive life.

So, the history of where this idea comes from is fascinating. This is oversimplifying but I’m going to give you the broad strokes: When you read women’s diaries and letters from basically up until 1900, they do not talk about feeling good during pregnancy, they mostly talk about being afraid to die, and being afraid that their babies would die, because the infant and maternal mortality rates were so high.

If you were an upper class white Christian woman, there was actually the idea that you were very fragile during pregnancy so there wasn’t any shame to being sick. But if you were a Black woman (or an immigrant woman), you were seen as pretty impervious to pain and supposed to be able to work through pregnancy. For Black women, especially, we still see the legacy of this idea in the maternal mortality and pain gap: Black women’s pain during pregnancy and postpartum is more likely to be ignored because of these racist ideas. (Linda Villarosa’s new book Under the Skin is essential reading on that topic, so is Killing the Black Body by Dorothy Roberts).

Then, in the 20th century, the maternal mortality and infant mortality rates improved dramatically because of modern medicine, and things like vaccines and clean drinking water, so your primary concern during pregnancy didn’t have to be: am I going to survive this. At the same time, women were starting to leave the domestic sphere more and more. While some mothers always worked, the majority of women didn’t work after they had kids. But that started changing as more women became educated, and tons of mothers went to work during WWII.

Then the men returned from war, and as a country we wanted those women back at home. So there was a huge pronatalist push, and during the ‘50s and ‘60s, the work of some popularized psychiatrists pushed the notion that if you weren’t happy during pregnancy, there was something wrong with you. If you wanted to keep working, there was something wrong with you, too. You were neurotic, and you hated your own femininity, these shrinks said. You needed to be reeducated.

Because I had hyperemesis myself, I was particularly disturbed by the story of a woman with a history of hyperemesis in Washington State in the 50s, which I heard about from Ziv Eisenberg, a historian who wrote his thesis about these psychiatrists. She had a previous miscarriage, one healthy child, and a therapeutic abortion because she was so sick. Doctors told her she was immature, hysterical, and had an unhealthy attachment to her father. Though they did ultimately support her in having another healthy baby, doctors “feared the patient’s ‘emotional difficulties’ would resurface and sterilized her.”

As to “Why did that process feel particularly important when it came to unpacking American Motherhood?” — I feel like so many of these ideas are just so deeply embedded for us, they’re subterranean. We don’t question them, because we assume they are true, because everyone says that shit about glowing. So showing that they came from somewhere, and often somewhere bad, is the first step towards ignoring these pressures.

I want to talk about your choice of the word “unsustainable” for the subtitle of the book. Not just the difficulty of American motherhood, or the strain of American motherhood, but the idea that there will be a breaking point. Do you feel like your ability to write the book is, in part, predicated on having reached that point yourself pretty early in the process? What advice do you have for moms who want to throw up their hands and do exactly what people keep telling them to do (care less, do less, try less, parent less) but feel paralyzed to make different choices? And how do we convince the bourgeois, progressive [often but not exclusively white] parents that doing less is also the route to more of race/class-based equity they articulate they value?

Yes, I think having such a difficult pregnancy with my older daughter had the silver lining of allowing me to throw out a lot of expectations that didn’t suit me. I guess I would say: it’s always baby steps. Is there one thing today that you don’t have to do that you could simply not do? I think it’s paralyzing to think you have to throw out your entire life and start over from a new paradigm. I also think I chose the word unsustainable because I don’t think individual choices are going to fix it; it’s unsustainable because we don’t have the support systems from our government, our work and our families to sustain it.

For the Times, you recently wrote that the issues that make it so hard for parents today “aren’t women’s issues. They aren’t urban issues and they aren’t mom issues. They are everybody issues.”

Sometimes I feel like we’re screaming it, we’re working so hard to make others’ understand it, and it kind of reminds me of this matrix that marketers in Hollywood put together about blockbusters: basically, women will go see things that men want to see (but men won’t go see things that women want to see), and old people will go see things that younger people will see (but not vice-versa), so the magic formula for a hit, and one that still largely abides today, is to market everything to a 19 year old boy, and trust that others will be so accustomed to this understanding of what they should care about, that they’ll go see it too. So we have parents who care a lot about parenting issues (until they out of it, and exhausted, and don’t have energy to organize to achieve changes), and moms who care a lot — but how do we get people on board for changes that don’t directly affect them? (This applies to, say, policies that adversely affect single people and non-parents, too — how do you get people to care about other people, even when their experiences aren’t precisely your own?)

This is sort of a depressing answer, because I think people just don’t listen to women. But I think people who are not moms need to talk about their own experiences with this stuff more in their own communities. The example I give in that piece is that paid leave is extremely popular among rural men, because it is VERY hard to get any elder care, child care, nursing care, you name it, in rural areas. If you are an hourly worker, and your wife just had a c-section, you want to be able to help her, and you might not be able to. You want paid leave so you can help her. That guy, not me, some liberal Brooklyn lady, is going to convince people in his community to change their minds.

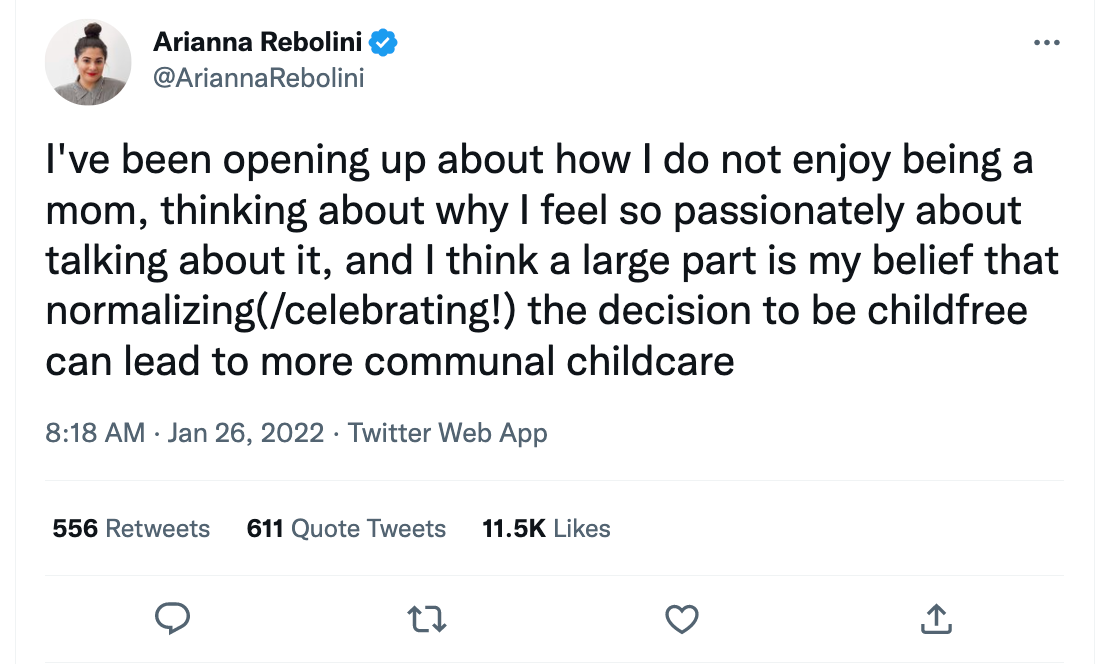

While I was putting together these questions, my friend and former coworker Arianna Rebolini posted on Instagram about a comment she made earlier this year that inspired reams of hate both on and off Twitter. In short, she said that she really was not enjoying being a mom. She purposefully didn’t hedge it with “I love my son so much.” She just wanted to be truthful about what she was experiencing.

I appreciate how Arianna connects the dots here: it’s not just that it’s important to be able to speak “your truth” or “your experience,” it’s that being more honest about these experiences can (?) should (?) lead us to different models of care (for kids and for one another), too.

You begin your conclusion with the importance of thinking about and just being with the reality of ambivalence towards parenting (or having kids at all). Can you talk more about why you hope that’s a primary takeaway from the book, and why it felt so important as a way of ending a book?

We have this cultural idea of motherhood that it’s supposed to sand off our rough edges — to be transformative. I remember this woman I talked to for the book, Angela, described believing that after her son was born “I thought I was going to magically be the most amazing version of myself. The angelic Angela.”

I think that’s a dangerous idea, because moms aren’t some new category of human. We are still just people, with a range of human emotion, and it leads to a lot of guilt and shame if we aren’t somehow magically transformed. I ended with this idea, because I think leaving space for each others’ real feelings is such an important part, and is such a doable part, of change. Whether that will lead to different models of care, I don’t know, maybe you’re more optimistic than I am about that. But it’s a start.

You can find Jess Grose on Instagram here and buy Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood here.

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s the monthly asynchronous book club (this month’s pick: Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow); there’s the weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads (this week’s is Friday thread on ‘what type of friend are you’ brought up A LOT), and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, which is what one reader once described to me as “it’s own little town.” There’s a dedicated place to talk about your plants, and your DIY projects (with experts who will tell you how to do things!!!), and all your various movement pursuits. There’s a place to ask for advice, and talk about how to navigate a sticky friendship, and find help in your job hunt, and get support as we all deal with our weird and wondrous bodies. Plus there is so much more — I promise, if there’s something you want to talk about, there’s a space for it, and if not, you create it, and people will come.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

One of the couples down the very short street from me just adopted their first baby. I don’t know them very well, but the first time I saw them with the baby all swaddled, I practically yelled at them to take my phone number and call me whenever they wanted someone else to just hold the baby for a minute so they could take a breath. Since I work from home, it’s a very real option that I can come over to help. Part of me is trying to enforce the old precedent from this town that everyone pitches in, as the old timers complain about how people don’t get together here anymore. My hope is to have a baby next year, and we’ll be three hours from a good hospital and our closest relatives will be a 16 hr drive. We chose where we settled, but whew a little additional infrastructure could mean so much, especially if we have any difficulties. Always appreciate you pushing these conversations and can’t wait to check out this book.

If my mom doesn't give me this book for Christmas I will be surprised and disappointed.

That Arianna Rebolini post...it is so important to be able to talk about that. And a related but distinct idea that a lot of our lives would be better if we didn't have kids. Like, my kid is one of the best things in my life -- but that's partly because my kid's existence makes it so difficult for other parts of my life to be good and sustainable. A ton of things would be better if I hadn't had him, say if he had been a third miscarriage and we'd given up. I wouldn't have *him* and at this point it's really crushing to imagine that, but, like, those first weeks of the pandemic when everyone else was talking about the exciting meals they were making and my husband kept asking what we should make, I kept saying "you don't get it, those people have extra time now. we do not have extra time."