stacey's dad is a bad dad

Here’s what I knew about Stacey’s dad in The Babysitter’s Club: he was a workaholic. That’s why Stacey’s parents had split up; that’s why he couldn’t make the time to pick her up at the train station; that’s why he was a bad dad. But for all of those negative connotations, I also knew that Stacey’s dad was an important, powerful people — or, at the very least, that’s how my tween brain internalized it, and the generalized idea of “workaholism.”

It’s been a long time since I spent my own babysitting money buying books about a club of babysitters, but the internet, amidst its raging trashfire tendencies, does provide periodic wonders, like the Babysitter’s Club Wiki, which describes Stacey’s dad, Edward, as such:

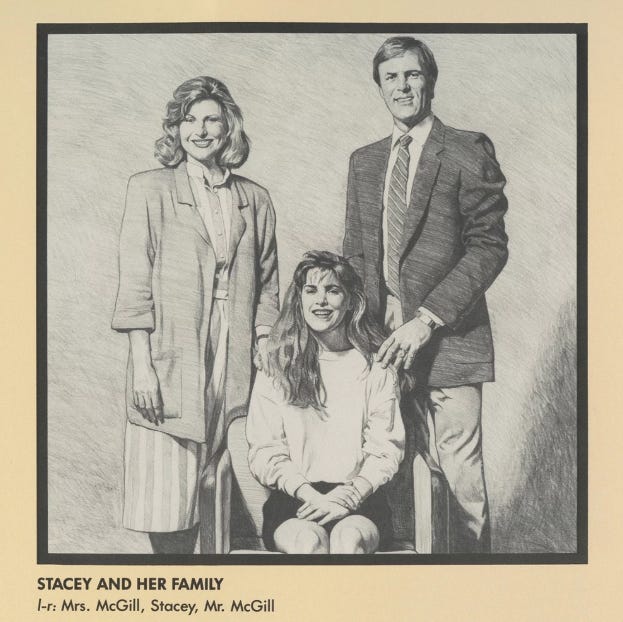

Oh, and there’s a “family photo” (apparently taken from the Babysitter’s Club CALENDAR, released in 1991?):

(As a pure bonus for the real BSC fans, here’s a description of Stacey’s “appearance”)

I’d been thinking about Stacey’s dad as I read some of the late ‘90s texts on workaholism, best articulated in the title of clinical psychologist Barbara Klinger’s book Workaholics: The Respectable Addiction. The book is addressed to actual workaholics (and those who love them) and, like the term “workaholic” itself, borrows significantly from theories of addiction and dependency of the time.

Within the framing of these books, workaholics are mostly (but not entirely) men; workaholics use work as a means to avoid and/or flee emotional intimacy; workaholics are workaholics because of personal choices, not as the result of structural influences. (The closest that one book comes: “Compounding the problem for the workaholic is a social and business structure that tactilely rewards work addiction. We are a nation of addicted workers primarily because we are a nation of addictive work organizations.”)

Some other characteristics of Workaholics, according to the “Respectable Addicts” book:

“Workaholics typically come from dysfunctional families, families whose patterns of behavior and interactions are not healthy”

“Workaholics typically work at play. They think about work strategies and problems on vacations, and even while making love. Such distractions help them avoid the intimacy they fear.”

“Many perfectionist homemakers are workaholics”

“The workaholic’s world is one of power, control, success, and prestige; of complexity, responsibility, ambition, and drive”

Apart from the *very brief* caveat about homemakers, it’s also very masculinist, very focused on the individual’s failure to uphold his end of the domestic covenant. The workaholic is self-centered, focused on power, success, and prestige — exactly the things that society values. He sucks as a Dad, and a partner, and probably as a friend, but what a good capitalist he is! (Which is to say, what a good American he is!)

And that, I think, is where that connotation that workaholism is secretly good formed in my brain (and so many others’). Under capitalism, it’s good to be a bad.

I’m reading other books/histories exploring the reasons that my parents’ generation of boomers (negotiating the workplace in the ‘80s and early ‘90s) felt so compelled to work all the time (Downsizing! Japan! Wholesale decline of unions and worker protections! Reaganism! Consultants who fired anyone without their own workaholic work ethic!) but for the purposes of my own millennial burnout project, I’m most interested in how millennials internalized and negotiated the models of workaholism we encountered in our own lives, whether in the form of Stacey’s dad, “successful” adults around or distant from us, and our own parents.

Workaholics were usually white middle-class men — driven by the (almost entirely) unspoken fear that they wouldn’t be able to reproduce their own social/class standing for the next generation. (All of the authors I read distinguished between a workaholic, who doesn’t have to work the number of hours he does to survive and/or provide for his family, and someone who works all the time because that’s what’s necessary to keep the family afloat). And if that anxiety manifests in the number of hours they put in the office and the overarching attitude towards work, it’ll certainly manifest in other ways. What’s weird, then, is that it somehow wasn’t bad enough (or bad enough to counteract our capitalist understandings of good) to prevent us from developing our own ethos of venerating overwork.

In fact, despite all the apparent ‘90s societal handwringing about workaholism and dissolution of marriages and/or families, the logic of capitalism is so backwards, and so tenacious, that we (quietly) convinced ourselves it was the only path to success. Unlike our parents, though — and this is crucial, I think — we decided it wouldn’t let it consume us at the cost of the family. Stacey’s Workaholic Dad was a dick because he neglected his family. Theoretical Grown Up Stacey has internalized those lessons not by reconsidering work under capitalism, or turning into a union advocate, but by arranging a schedule that allows her to be everything to her job and everything to her kids (and very little to herself or society at large).

Workaholics, at least according to this configuration, were selfish. Middle Class/Middle Class Aspiring Millennials reject the self-centerism (ironic, given our reputation) for self+work+family-centerism. We work. We exercise. We talk with our parents but much more if they’re also providing secondary child care for us. We devote a lot of energy to cultivating relationships with our children and, secondarily, our partner. We try out new organic recipes (for our families). We find time to go on a yearly girls’ trip with our friends, but our legitimate social lives are secondary, as are any activities that don’t fall under the to-do list we’ve acquired to somehow manage the self+work+family conflagration of responsibilities. (Or, like me, you just don’t have kids at all, and then spend even more time on work+self+partner.)

In short: we’ve one-upped the Bad Workaholic Dad. Sure, he was kinda miserable. But he was also a success, and if we just worked harder, we could counteract the miserableness. I think we’ve figured out this thesis is pretty false, but the only way to break the cycle — to not inadvertently guide our children to look at our Burnout as something venerable — is to stop trying so damn hard to make it look easy, or desirable, or possible if you just sleep a little less and try a little more and settle for a little less.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Maybe that’s something we should talk about — not just amongst ourselves, but with our children — a bit more.

With that said, I would *love* to hear your memories of how “workaholic” signified for you in the ‘80s and ‘90s. It’s easy: just reply to this email, or find me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com

Things I wrote this week: 14 Millennials Talk About How They Made Home Ownership Happen

Things I Read and Loved / Was Compelled By This Week:

A fascinating interview with the costumer designer for Fleabag (I can’t believe people thought the jumpsuit was BLACK?!?!)

His DNA helped solve a brutal jailhouse rape. The victim: his grandmother.

Terese Marie Mailhot: “sometimes genocide looks like a slow burn from the outside, but inside, here with me, it looks like a wildfire that was already there when I was just a little girl”

Hootie is GOOD, fight me

A convincing argument that (some) Democrats have learned the wrong lesson from Clinton’s impeachment

Why it’s becoming ever more difficult to read in prison — and why that matters

This piece is very hard to explain but equal parts terrifying and hilarious and enthralling, which is to say, the runner up to this week’s just trust me (NYT)

This week’s actual just trust me

As always, if you know someone who’d like this sort of thing in their inbox once a week-ish, just forward it their way. You can subscribe (and find the newsletter in online, linkable form) here. Please forgive any typos or weirdly-written sentences; the inattention to detail is what allows me to make the mental space to get this thing out for free, even during book leave.