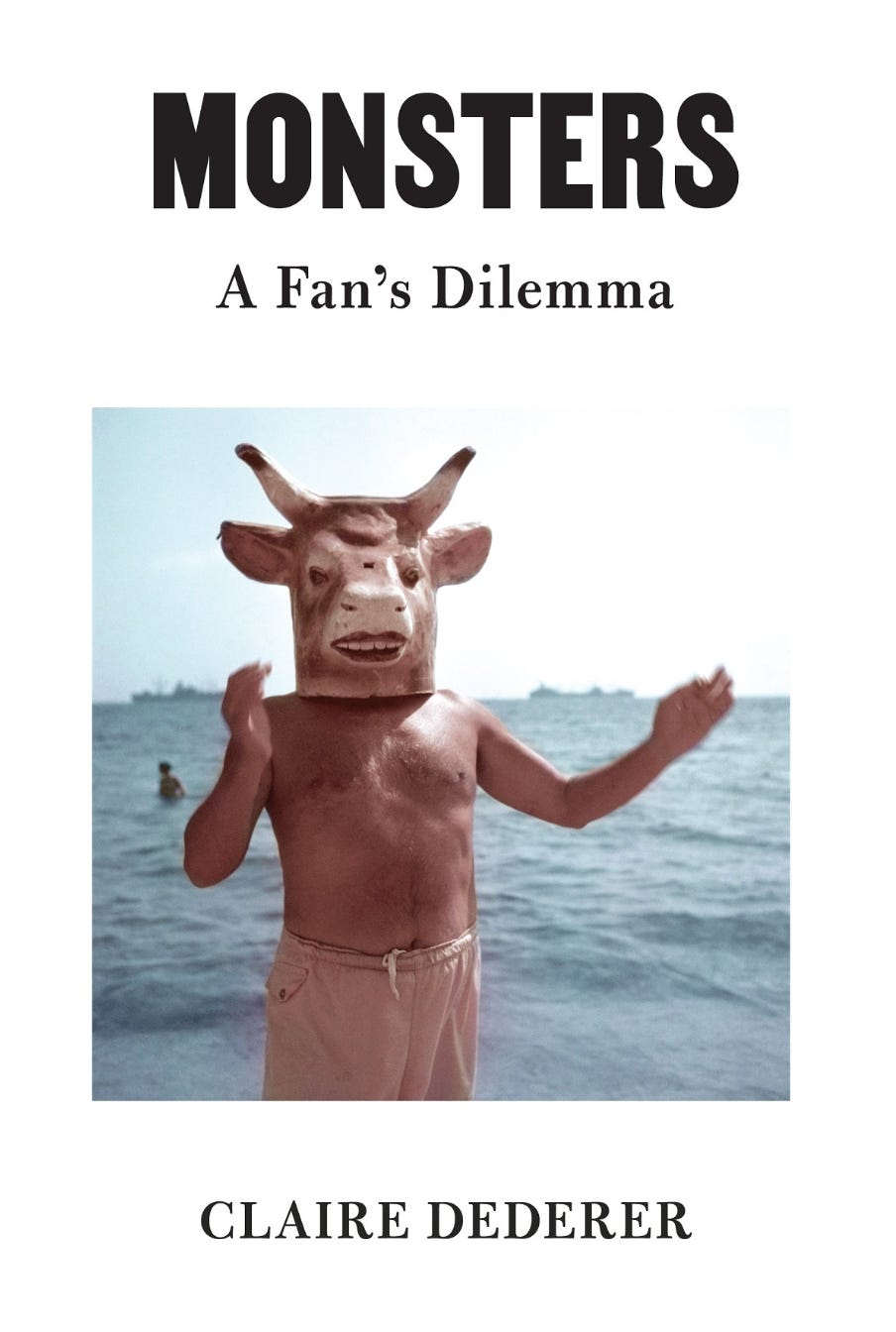

What do we do with the art of monstrous men? That’s the question that animates Monsters: A Fan’s DilemmaWhen a galley of this book first arrived in the mail last year, I was struck by the cover (who wouldn’t be!) but worried it would lead me the same place so many of these conversations have led me: into unsatisfying knots, stuck between the poles of rejecting whole bodies of work and mealy-mouthed justification of separating the art from the artist. Maybe you arrived at a place of clarity about how to deal with the art of Woody Allen or Picasso or any film with a Miramax banner before it. I never did.

I put Monsters on the very top of the stack of books that sits next to me while I write, so I could let it intimidate me into reading it. And it turned into one of the most electrifying reading experiences of my year: the writing crackles, and Dederer’s thinking is so rigorous and challenging and inviting. Each chapter says: I’m trying to figure this out. Wanna come? You won’t end up with a clear stance on what to do with the art of monstrous men. But you will end up with a clearer understanding of yourself. So treat this interview as an enticement. We’re trying to figure this out. Wanna come?

You can buy Monsters here (now in paperback!), and follow Claire Dederer on Instagram here.

Monsters are so expansive!! How do we even start to talk about them!!! I mean, obviously, this is what your book attempts (and, in my opinion, gloriously succeeds) at doing, but how do we begin to talk about them in this Q&A, while maintaining the expansiveness of the book….that’s hard. So maybe let’s start by talking about the stain, and the genius?

Well, when I first started thinking about this problem—the problem of what to do with the art of monstrous men—I called them by that name, exactly: monsters. But the term began to trouble me. The word monster doesn’t hold up well. It starts to seem a little silly or overblown or, let’s go all the way with it, hysterical. And of course no one is entirely a monster. People are complex. To call someone a monster is to reduce them to just one aspect of the self. I came across the metaphor of the stain; the idea that the artist’s biography has colored our experience of their work, whether we want it to or not. The word monster is like a suitcase packed full of rage—the rage that gives rise to its utterance, the rage with which it is heard, whether by friend or foe of the monster in question. The stain is something else again. The stain is just plain sad. Indelibly sad.

No one wants the stain to happen. It just does. We don’t get to make decisions about the stain. It’s already too late. It touches everything. Our understanding of the work has taken on a new color, whether we like it or not.

The tainting of the work is less a question of philosophical decision-making as it is a question of pragmatics, or plain reality. That’s why the stain makes such a powerful metaphor: its suddenness, its permanence, and above all its inexorable realness. The stain is simply something that happens. The stain is not a choice. The stain is not a decision we make.

Indelibility is not voluntary. When someone says we ought to separate the art from the artist, they’re saying: remove the stain. Let the work be unstained. But that’s not how stains work.

We watch the glass fall to the floor; we don’t get to decide whether the wine will spread across the carpet.

As for the genius: There are people who seem basically unstainable—or even seem to benefit from the stain.

A certain kind of person demanded to be loved, expected to be loved, no matter how bad his behavior—and we (oh, we) all agreed he was worthy of love. This was the person called the genius. This person might be stained—in fact almost always is stained—but the stain seems not to dent his importance. His primacy.

The genius is a proposition. He’s a fantasy that we have collectively. The genius isn’t so much a kind of person as a status of person: a person who can do whatever he wants.

A genius has special power, and with that special power comes a special dispensation. Genius gets a hall pass. We count ourselves lucky he walks among us; who are we to say that he must also behave himself? Our fandom is a necessary ingredient of his greatness.

Who gets to be a genius? What does the genius get away with? Why does the audience need the genius, and vice versa? These were questions that animated my writing.

This book is, amongst other things, an autobiography of an audience. Can you talk more about the conception of audience-as-consumer (and, you know, neoliberalism) that comes to hang out so squarely in your analysis? (I’m thinking here about how we see consumption as some sort of moral choice, a way of advertising a moral stance, our only way of “voting,” etc. etc., and the subsequent need to act and declare choices about the art of monsters) I’m thinking, too, about the killer line near the end of the book: “The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one. You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.”

I think that there’s this odd thing that happens when we look at this problem of what to do with art made by flawed people. Someone—often a woman—raises her hand and says, “Hey, this famous man did this shitty thing.” In the aftermath of her speech-act, we leapfrog over a lot of different responses and end up intensely focused on the individual consumer’s response: Well, are you going to buy the album or not?

In the book, I draw on Mark Fisher’s thinking in the excellent book Capitalist Realism to talk about this impulse toward individual, consumer response. Because we are atomized individuals with no collective power, we are left with this single response: a grandiose yet ultimately meaningless sense of the importance of our purchases.

Art does have a special status—the experience of walking through a museum is different from, say, buying a screwdriver—but when we seek to solve its ethical dilemmas, we approach the problem in our role as consumers. An inherently corrupt role—because under capitalism, monstrousness applies to everyone. Am I a monster? I asked. And yes, we all are. Yes, I am.

I recently spoke with an Austrian journalist who asked me if that was a sort of a copout. And I said, maybe, but it has the benefit, in my opinion, of being true.

We attempt to enact morality through using our judgment when we buy stuff, but our judgment doesn’t make us better consumers—it actually makes us more trapped in the spectacle, because we believe we have control over it. What if instead we accepted the falsity of the spectacle altogether?

Condemnation of the canceled celebrity affirms the idea that there is some positive celebrity who does not have the stain of the canceled celebrity. The bad celebrity, once again, reinforces the idea of the good celebrity, a thing which doesn’t exist, because celebrities are not agents of morality, they’re reproducible images.

The fact is that our consumption, or lack thereof, of the work is essentially meaningless.

We are left with the art, which illuminates and magnifies our world. Which we love, whether we want to or not.

In one of my favorite sections of the book, you write that “biography used to be something you sought out, yearned for, actively pursued. Now it falls on your head all day long…[...]...We swim in biography; we are sick with biography.”

The unavoidable biography makes it impossible to avoid knowing art without knowledge of the artist, or without an abundance of knowledge about the artist. (And abundance isn’t necessarily knowing everything about their lives so much as always knowing things, always knowing the key points, the top Google hits, the primary and secondary scandals and meta-scandals). Women seem so much more susceptible to this abundance of biography, this over-knowing and staining — in part because interviews and conversations with public-facing women are so often fixated on elements of biography, of the intimate and domestic….whereas interviews and conversations with men are often allowed to stay “with the work.” You see something similar with “small screen stars” (reality stars, online influencer, bloggers, YouTube stars) whose fame is rooted in the availability of their biography, their biography as art. I’ve watched this abundance of biography curdle again and again, and small rifts and missteps morph monstrous.

How much of this has to do with knowing too much and how much has to do with the incessant need, as audience, to dig until you find the monster you wanted to be there in the first place?

This is a really smart point, about how biography muscles its way into the public personae of female artists. I’ll be honest, I don’t really care very much about how this biographical intrusion affects artists—that’s a very niche problem. I do care about how it affects audiences, the constant reaffirmation of the idea that every aspect of a woman’s domesticity is there to be perceived, to be a spectacle. The way it contributes to the sense that every woman’s most intimate choices can be judged.

Regarding the inevitable curdling: I’m interested in this idea of the digging audience. I wonder if it’s just a function of the way the internet monetizes information—you keep going, keep asking, keep unearthing, because the whole machine is set up for exactly that.

I don’t think I’ve ever read someone explain Harry Potter fandom as effectively and empathetically as you do — which I think has a lot to do with being very close to people for whom it was essential, but also having a modicum of distance from it, too. Can you talk a bit about the strength of the relationship between reader and this greater textual world, and the ways J.K. Rowling’s particular monstrosity challenges it?

Yeah, I had one kid who was very, very, very into Harry Potter—read all the books multiple times; went to LeakyCon, the Harry Potter conference jam-packed with 12-year-olds in full regalia; became a fan of the wizard rock band Harry and the Potters. Kids back then communicated their love for the books all over the world, zinging that love back and forth, computer to computer. We all need a place to feel like we belong, and the world of Harry Potter does a great job of creating a sense of belonging. The kids built mind palaces out of this world; resided there when life got rough, as is pretty much inevitable in early adolescence.

Oftentimes the kids who most need this sense of belonging are kids who grow up to be queer or trans. These are the kids who, as adults, have been sold out by Rowling’s anti-trans statements and tweets. Their dreamscape was taken away from them by the stain. They lost that imagined landscape where great swathes of their childhood had taken place. Rowling’s hatefulness—not toward just anyone, but toward the very population who’d found her books indispensable—changed the experience of reading these books about acceptance and love.

Of course, since I wrote the book, JKR has doubled down and it’s just been so painful for many people to witness. And to see other people untroubled by her statements.

What’s the bad faith reading of this book — and how would you counter it, other than to say stop being such a bad faith motherfucker?

Ha, yeah, the bad faith reader was very much on my mind as I wrote. Sometimes debilitatingly so, which I don’t think is an uncommon experience for writers these days. I think navigating our fear of the bad faith reader has becomes an everyday part of the process.

My own particular imaginary bad faith reader is, in many ways, the universal bad faith reader: the reader who asks “Why should we care what you think?” Obviously this voice is known to all writers. It was particularly difficult to navigate with this book because I was writing out of my own subjectivity. One of the projects of the book is to undermine authority and ask the critics to confess their own subjectivity, their own biography. It therefore became important have the voice and form of the book underline its message—that of valorizing individual response. Which is a scary thing to do! Who cares about your individual response?

Toward the end of editing the book, I was lucky enough to read an interview with Melissa Febos where she exhorted writers to be conscientious of all your possible readers, but do not write for the bad faith reader. This was enormously helpful as I went into the publication process.

This book is sneakily funny. Why did that feel important, amidst it all? Which reminds me: there’s a very sneakily funny section of the “Am I a Monster” chapter, where you talk about how women aren’t really allowed to say things like “I want to write a really important book,” or a really ambitious book, or even just a really great book, but then you tell a male author friend that you want to do that, and he says: WELCOME TO THE THUNDERDOME. And it feels awesome, at least sort of. What does it feel like now?

Thank you! Funniness is crucial—this book is not funny in order to soften its blows, or in order to make me as a writer more palatable, or even to disarm the reader. It’s funny because this is, at its core, a story of heartbreak—the sadness that comes when something we truly love is stained. And for me sadness and funniness are always bound up together—that’s what survival looks like. (Not to be melodramatic.)

What does it feel like now? A gigantic relief. Many people read the book on its own terms, understood what I was trying to do, responded to what I was trying to do. I genuinely did not expect that to happen. So maybe I no longer even want the thunderdome? Maybe now I just want the relief of being comprehended. ●

You can buy Monsters here (now in paperback!), and follow Claire Dederer on Instagram here.

Probably around 7 years ago, Jerry Saltz (famous NYC art critic with large social media following) posted something about Picasso on Instagram. A woman commented that she was unable to look at him the same way after watching Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette. I liked her comment and replied below agreeing with her. Jerry Saltz systematically went through the large comment section and blocked every single person (myself included) that criticized or questioned Picasso’s art due to his known misogynistic behavior. Essentially silencing all dissent, mostly from his female audience. (He famously blocks people who disagree with him all the time) FWIW, I have an undergraduate degree in art history and a masters in art conservation, at the time I worked for a museum, I feel more than qualified to voice my take on Picasso. I agree that the stain doesn’t make up the whole, I don’t hate Picasso and I very much appreciate his contribution to art, but Jerry’s silencing of anyone who disagrees with his “genius” narrative really irks me, and that stain has destroyed any credibility he had (IMO) as a critic. I’m still working through how I feel about the various “monsters” I encounter, thanks for this thoughtful discourse!

First, love that I thought this was going to be a column about laundry and was so there for it. Second, I really love the idea of 'the stain.' Even outside of the realm of celebrity, it feels so applicable to the way we navigate learning the whole sum of a person. It's often as if you're having a conversation and there's a giant red wine stain down the other person's shirt and you're left wondering - do we talk about that giant red wine stain? Do I ignore it? Will they ignore it? Should I offer a Shout wipe? Why haven't they changed their shirt? Is this their only shirt? Is that wine stain from today or did they try to wash away a previous stain, fail, and yet choose to wear the shirt anyway? Looking forward to diving into this book!