This is the weekend edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

In the United States, organizations where employees have been largely working from home for the past 16 months are having a mild freak-out. Depending on the organization, they’re hemming and hawing. They’re treading water. They’re having seemingly endless meetings with HR. They’re analyzing focus group data and surveys, and drafting carefully worded “back to the office” plans. And they’re dealing with or anticipating or totally ignoring employee blowback.

Some companies are doing an objectively okay-to-good job — and I know this not because the companies have told me they’re doing a good job (most companies would) but because employees have sent me their plans. A few examples:

The Big Company Shift:

I work for a large, Fortune 100 company headquartered in NYC that has announced the office is open for whoever wants to use it whenever starting June 14 and that starting after Labor Day, everyone is required to work from office three days a week (Tuesday to Thursday) with 30 days notice given before this all begins. This is a company that previously required manager approval for work from home, and capped the number of days allowed to work from home a year — so definitely a major shift for them.

The Small Branch Total Flex:

I work for a small branch of a company (15 people or so) and they basically have said we can continue to be fully flexible. No requirement to come to office for foreseeable future. Some people come daily, others once every two weeks to check in. I was told if they do make a requirement, it will likely be just one to two days a week. It’s actually been a pleasant but shocking 180 from before Covid. They were pretty old school and generally expected to be in office 8:30-5:00 no matter what.

The Options:

Early in 2021 folks started to work on the plan to open up campus & emerge from lockdown. Employees were offered three options, 1) 100% on campus, 2) 100% work from home, 3) hybrid - Tues, Weds, Thurs required on campus, Mon & Fri office or home. Option 2 comes with a stipend for equipment. Option 3 does not.

There is a phased reopening beginning on July 6. They'll bring in more people every couple of weeks giving employees 60 days notice to plan. Conditions will be monitored in case the situation changes.

The goal is to have employees with desk assignments all transitioned by September 13. We were asked if we had special considerations regarding the timing of returning to the office, i.e. childcare.

The 40% Rule:

I work for a large public policy nonprofit, and they've been surprisingly flexible! We'll be required in the office 40% of the time (calculated by month), and how that 40% is allocated is totally up to each person. Also, once they announce a reopening date, people have three months before they have to work 40% in the office (so, no one is required in their seat on day one of reopening).

Pre-covid, everyone was basically expected to be in the office 9-5, M-F. There was no official telework policy, which meant that flexible/chill bosses would basically allow off-the-book WFH for their teams, and everyone else did not. I do think management would have had a mutiny on their hands if they tried to require everyone to work in the office full time again, but now pretty much everyone is pleased with the new policy going forward.

The Zillow:

I work for Zillow, so this is definitely on the corporate side, rather than small start-up. I think it was about Q3 or Q4 2020 when they decided to go fully remote HQ. This included job designations of either office/hybrid/remote. Office/hybrid roles require some sort of in-person duties, while remote can be fully digital. Those in remote roles can choose to be hybrid or in-office. Hybrid roles can choose to be hybrid or in-office as well. So essentially, unless your job requires you to be in-office every day, you get to choose how much time you expect to be in the office.

Our offices are currently undergoing renovations to remove some of the open-plan seating in favor of group collaboration and meeting areas. Not sure how hot-swap seating will be setup, but will be available. Salary is not being adjusted if someone moves from a major city to a different locale, though we are limited in being able to work outside the country. Benefits now offers $150/mo to expense for "home office", which can be used for office furniture, supplies, or even internet service. There's also a moving-planner service for employees to use to help plan a move more than 50 miles.

A friend of mine works for a small but global nonprofit with a HQ in an urban area, and her plan — in office full day on Tuesday to Thursday, with exceptions on the beginning/end of the day for caregiving responsibilities negotiated with managers — feels like the median response. Not spectacular or even paradigm-shifting, maybe just a litttttttle reflexively controlling, but still acknowledging that there’s just no need, given the rhythms of their work, to be in the office five days a week.

Right now, most organizations are focused on the hours, days, and location of work— which makes sense, because that’s the first layer of questions that employees have about an eventual return. Smart organizations are actually listening to what their employees are telling them about what flexibility should look like, what matters and what’s lacking, what they’ve struggled with working from home and what they miss. Unsmart companies are returning to the status quo because they don’t trust their workers, they have weird fantasy scenarios about spontaneous hallway collaboration, they’re resistant to learning how to manage in ways that don’t involve direct sight lines, or they’re just straight up assholes who want to control their employees’ lives.

And then there are the weird hybrids: a company that’s decided that yes, we’ll let you work from home, but only on Wednesdays, because we know that you’ll slack off if you’re working from home on Monday or Friday. (A company that only allows employees to work from home midweek is a company that doesn’t trust their workers and, again, has much bigger problems!) Or the company that’s decided that they’ll rotate half of their employees into the office one week, then the other half the other week — making it effectively impossible to find consistent care solutions. This is the sort of problem that even one parent on the planning committee grappling with childcare could’ve anticipated.

And who knows, maybe that idea will disappear in a few months. A lot of well-intended ideas will, as will employees themselves. There’s already notable anecdata of people quitting their jobs when indiscriminately forced to return to the office. Workers are deeply burnt out and frustrated with their companies; for many, a truly shitty back to the office plan (coupled with a generally good job market) is the last straw. The best thinkers, innovators, and workers will go where their work is valued and their organization makes policy that underlines their trust and respect for their workers, even if that means switching fields entirely. (See especially: those working in education, academia, and non-profits).

Companies will either decide to shift their policies to become competitive, or they’ll slowly atrophy, because a company that foists full-time back to work on its employees with no reason has much bigger problems with company culture, control, and bad management. A shitty back to the office plan belies a shitty office culture, full stop.

For the companies that are trying to make flexibility work, there’s going to be periods of discomfort, and frustration, and confusion. The best corporate posture I’ve seen involves the straightforward acknowledgment of such: this is going to be complicated, and iterative, and take time to figure out, but we’re committed to making it work. These companies are anticipating, if not already figuring out how to proactively solve, a second layer of questions. After they figure out the hours, and the days, and the location, what happens to hierarchies, to pay, to communication strategies, to barriers instead of boundaries, to hiring and promotion and retention stats? How, in other words, do we allow people to work differently, while also leveling the playing field?

The “good” news is that the pre-COVID, the in-office playing field was unlevel as shit. It favored and advanced a certain type of worker, with a certain type of working style, and a certain availability and eagerness to work in person in an office. It favored extroverts, it favored dudes, it favored neurotypical workers with no physical or psychological conditions that would prevent them from sitting in a chair for nine hours a day, five days a week. It privileged people with the desire and ability to live in proximity to their industry hubs. It implicitly or explicitly promoted those without care responsibilities and/or those most effective at masking or ignoring care responsibilities.

We should stop buying the farcical argument that in-office work was some ideal opportunity scenario. It was deeply, deeply exclusionary for many — it’s just that those people aren’t the ones asked to write the thinkpieces about the benefits of returning to the office.

Genuine flexibility can counteract some of the natural hierarchies of in-office work, but it can also create new ones. As economist Nicolas Bloom put it in a recent interview with Bloomberg, "My fear is the biggest cost in the long run is all the single men come in 5 days a week, and college-educated women with a 6-year-old and an 8-year-old come in 2 days a week. Years down the road there’s a huge difference in promotion rates and you have a diversity crisis."

This isn’t idle speculation — anyone with experience in the workplace will tell you that this will almost certainly happen. Managers who haven’t learned to recognize work or productivity save through in-person interaction will continue to promote those who work and produce in a way that’s visible and legible to them. And the people who will best equipped (and societally facilitated) to do that visible, legible work are the same people who excelled in the pre-COVID office: white, able-bodied men with fewer or nonexistent domestic demands.

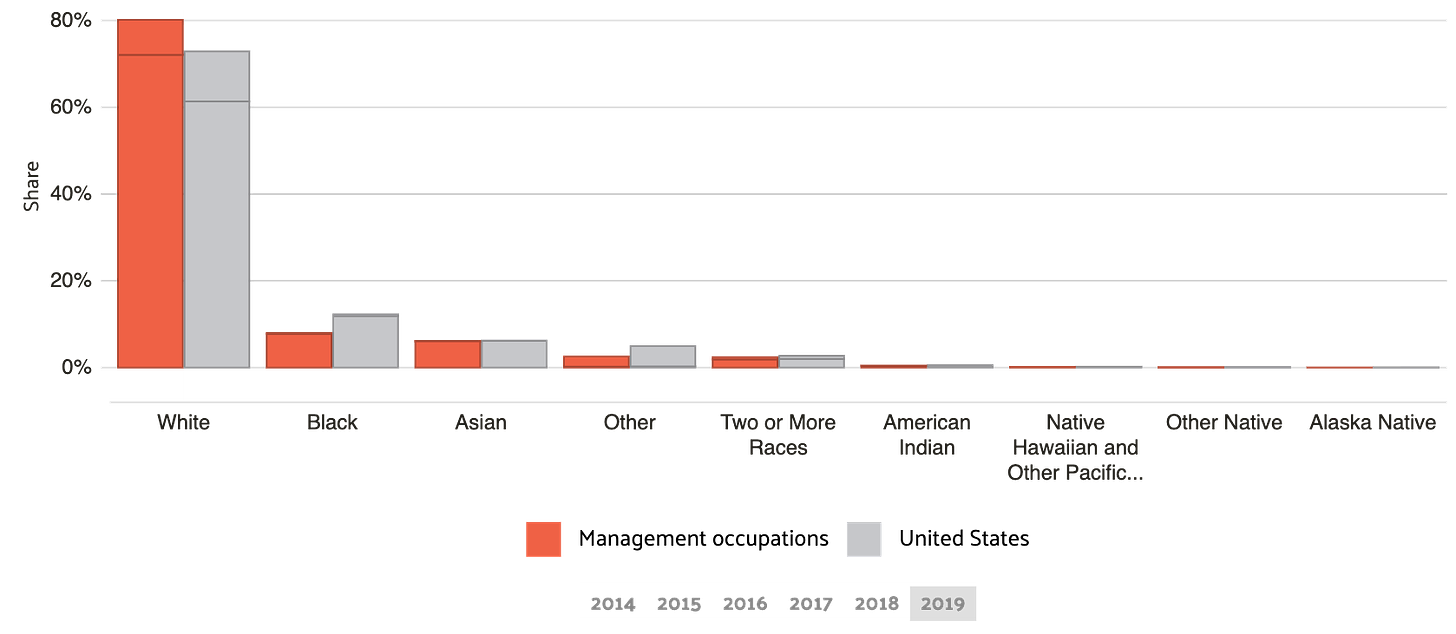

In this scenario, people who prefer to work remotely, and on more flexible schedules, will form a secondary class of worker — and that secondary class will be filled with the same people who have fewer privileges within the current social hierarchy, especially if the managerial class continues to reproduce its racial dynamics. (In the chart below, the block on the top of the chart represents “White Hispanic” — which makes up 8.8% of the managerial class. White Non-Hispanics account for 72%. More data here).

“We simply do not trust people dissimilar from ourselves to work without direct surveillance,” sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom writes in her recent newsletter. “….You also have the problem of managerial bias regarding which workers “need” supervision. Black workers have long reported that they are less likely to be offered flexible work arrangements than are their white counterparts. Ask a middle-class, white-collar Black woman how easy it is for her to call in to tell her colleagues she will be working from home today and see how she stares at you.”

And there’s good reason for Black workers to want to work from home, too. As McMillan Cottom points out:

There is a persistent belief that Black workers cannot be trusted with the autonomy that is standard to our profession, much less to the autonomy that isn’t common to it. But a lot of Black workers report that the freedom from managing the hostility in white-dominant workplaces improves their productivity and well-being. Folks get tired of being the “only” or the hyper-visible or your “Black work friend.” There is not only freedom in staying home some of the time, but for Black workers, it’s also super beneficial for this reason.

People have all sorts of reasons for wanting to work remotely. It might make them better workers. It might allow them to maintain their physical and emotional well-being in a way that’s incompatible with full time office work. It might provide relief from micro-aggressions, or actual aggressions in the form of yelling and abuse. It might just allow them to live better lives. But those decisions, at least currently, are poised to have long-term negative consequences.

The majority white managerial class’s internalized biases will reproduce a majority white managerial class. Extroverts who revel with being in the office five days a week will excel. Leadership will remain snowcapped. Disabled workers will be second-class workers. Salary gaps will widen. It will happen so gradually, so seemingly “naturally,” that it won’t necessarily be visible until the data makes it undeniable. Remote workers will be conceived of and compensated as less valuable workers, regardless of how much value they’re actually adding to the company.

How do you combat this scenario? Charlie and I thought about this a lot while writing our forthcoming book on flexible work, and spent significant time talking to people who’ve already been working through these questions in their own hybrid companies pre-COVID. The key, again, is actually leveling the playing field. And sometimes that means not just giving everyone freedom to figure out their ideal, but placing limits on the spaces that will naturally position a worker’s labor to become more visible and legible. In short: if you’re actually invested in creating an equitable, flexible workplace, not everyone can come into the office all day, every day.

This is really hard for people to hear, because any sort of limit seems counter to the connotations of freedom that accompany a shift to a hybrid workplace. But “flexible” doesn’t mean “total freedom.” There are still boundaries of behavior — and, hopefully, company-led guardrails to prevent workers from working all the time. And if an organization is invested in protecting workers from their own burnout compulsions, they should also be invested in protecting managers from their own implicit biases.

What this means in practice: figuring out minimums, which companies have already been doing, but also figuring out maximums. “But what if I need to leave the house every day,” is the response I often hear (from extroverts) to these proposals. Or: “But what if I don’t have a great workspace at home.” Here is when I tell you, again, that working remotely does not necessarily have to mean working from the same couch where you have worked for the entirety of the pandemic. Coffee shops, libraries, friends’ kitchen tables, co-working spaces, there are so many places where people can work for a day or two that are not the office. This might mean your company provides a small monthly subsidy for office or co-working drop-in fees. But that is nothing compared to eventually dealing with the regressive, inequitable shitshow that’s going to happen if you don’t try to grapple with these questions now.

Apart from maximums, it also means purposeful retraining of how to measure work outcomes, purposeful implicit bias training, and purposefully diversifying the managerial class at your organization to mirror the worker population in both demographics and hybrid working scenario. In the book, we call this breaking up the monoculture, which is oftentimes not recognized as monoculture because it’s just the status quo — but a status quo that, again, has been organized around the needs of a certain type of worker.

It’s not that everyone needs to be managed by someone who looks and works exactly like them. It’s that the standards of what rewarded work looks like, and the sort of employee most trusted to produce it, need to be steadily and mindfully eroded. One way to do so: hire and promote people who understand the value of different types of workers, because they themselves are those workers.

(Of course, people can devalue the work of others like them all the time — there are certainly women who are ruthless and exacting when it comes to other women in the workplace, which is a study in internalized misogyny and perverted lean-in-ism that merits its own piece. Those are not the people you want to hire.)

None of this is going to be easy. But none of this was easy before the pandemic, either — and it was certainly wasn’t equitable. You can think of wrangling your employees back to the office, as many recalcitrant executives have, as herding ornery cats. Or you can think of it as an opportunity to become the diverse, equitable, and inclusive organization you declare yourself to be on your “About Us” page. If employers actually value hard work, they should do some of their own.

Things I Read and Loved This Week:

“Of course cis people are being weird about Elliot Page’s body”

These young accordianists!!!!

That classic tablet game HUGE KID CAESARIAN BIRTH IN HOSPITAL

The Racism of the ‘Hard-to-Find’ Qualified Black Candidate Trope

I love thinking about friendship from an anthropological perspective

How the personal computer broke the body

This week’s just trust me

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here. There’s a new, private, subscriber-only channel for job hunting that is already transforming resumes.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

But Anne how ever will we function as a workforce if we are not forced to attend a purely performative lunch-break baby shower or "employee appreciation" pizza party.

This line from the Just Trust Me has me nodding my head, yep, yep:

"My body and soul are hungover, dehydrated and malnourished after this last decade of 2009 onward."