This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing. Subscribers: If you haven’t activated your invitation to Sidechannel, email me for a new one! Along with Eric Newcomer, I’ll be interviewing the CEO of Cameo this Thursday afternoon (4/22) at 4 pm ET / 1 pm PT. If you’re curious about Sidechannel, read more about it here.

"We have four positions open," Christy Welch, the co-owner of Black Cat Bake Shop, told the Missoulian. "One is for a barista. We've gotten maybe three to four applications for that job, when we would usually get 20-25. We have three back-of-house positions and we've gotten no applications."

Current pay for most of those positions: $10.50 an hour. Overnight shifts get $11.50. Tips are shared. (Current average rental cost for a one-bedroom in Missoula: $1010 a month, up 27% from last year

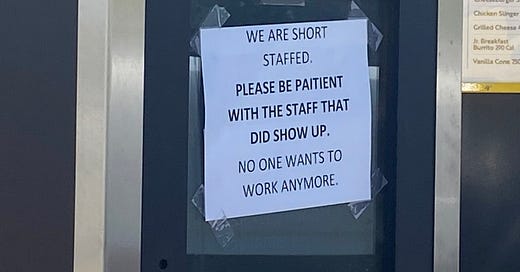

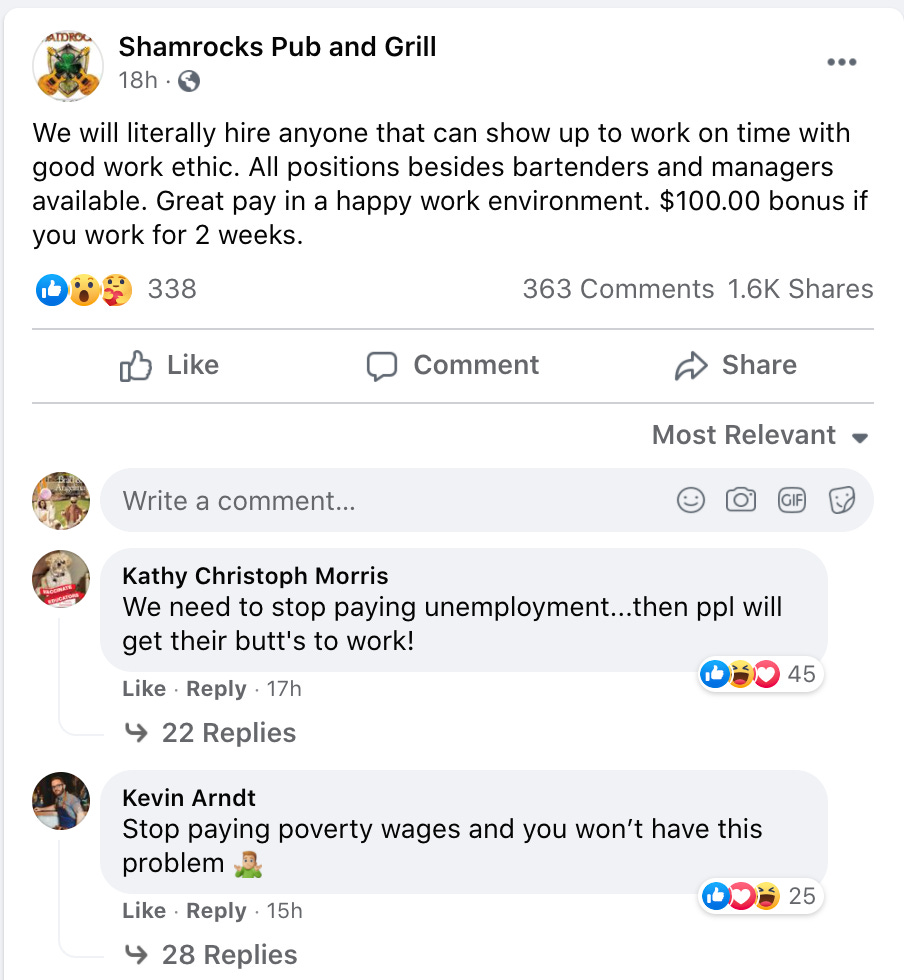

You can find similar stories in Toledo, in Chicago, in Albuquerque, in Salt Lake City, in Vermont, in Lexington, in Richmond, in Nebraska, in Rhode Island, in South Carolina — truly all over the U.S.. Many of the business owners in these pieces channel Sen. Lindsey Graham in some way, suggesting that unemployment benefits have made workers lazy.

In Waterville, Ohio, for instance, there’s this sad, sad song about the difficulties finding workers at Dale’s Bar & Grill — which somehow fails to mention that the owner is a Covid hoaxer (he believes that doctors have been falsely labeling deaths as Covid-related) and has brazenly violated masking rules, and did not require employees to wear masks.

Some of these unfillable jobs are in places without affordable housing — or, like Missoula, where cost of living has continued to rise over the course of the pandemic. Others are seasonal and/or tourist-adjacent. Many are at restaurants, particularly fast-food. Some are at retail stores with unpredictable scheduling. What goes unsaid in many of these stories is the fact that the jobs are shit jobs, whether because of the unsustainability of the pay, the Covid exposure, or the shit treatment they’ll receive from tourists.

Stick with me here, but what if people weren’t lazy — and instead, for the first time in a long time, were able to say no to exploitative working conditions and poverty-level wages? And what if business owners are scandalized, dismayed, frustrated, or bewildered by this scenario because their pre-pandemic business models were predicated on a steady stream of non-unionized labor with no other options? It’s not the labor force that’s breaking. It’s the economic model.

Unemployment benefits have offered a steady paycheck while you figure out your options. Put differently: a version of the safety net that’s been missing from most American employment, and, by extension, the ability to say no. No, I don’t have to work for a restaurant that only gives me my hours three days ahead of time, thus making it nearly impossible to find reliable childcare. No, I don’t have to work clopen shifts. No, I don’t have to expect a job without sick leave or paid time off. No, I don’t have to deal with asshole customers or managers who degrade me without consequence. No, I don’t have to work in a job with significant, accumulating health risks.

It’s about the money, but it’s more than that. Here’s Adam Reiner in a recent piece for The Restaurant Manifesto:

The assumption that the attractiveness of unemployment benefits is causing labor shortage is an oversimplification. But restaurant workers are accustomed to being blamed for things that aren’t our fault. We’re trained to feel responsible for failures even when we ought not be—by people that are disappointed with their food when they didn’t understand what they were ordering; by large parties that arrive over an hour late for their reservation and are refused a table; or just by average run-of-the-mill miserable patrons who will themselves into having a miserable experience for which we, in turn, are expected to shoulder the guilt.

Meanwhile, in the name of hospitality, ownership and management continually elevate the status of guests above the status of their employees, cowering to guests regardless of whether their complaints have merit. They obsess over the staff’s failures without celebrating its successes. They’ll say it’s tough love, but many restaurant workers now realize that tough love is the only kind of love the industry has to offer.

So, why should restaurant workers feel compelled to help carry the burden for a struggling industry that so often took them for granted when times were good?

As Reiner notes at the beginning of the piece, there are exceptions to this rule: endlessly humane and compassionate owners who did everything they could, before and during the pandemic, to make restaurant jobs good jobs. But they are, again, exceptional. Not every owner is as reckless and manipulative as Dale from Dale’s Fucking Bar & Grill, but plenty are. UI gives workers the opportunity to say fuck you, Dale, Target’s paying $15 an hour; fuck you, Dale, I’m enrolling in school; fuck you, Dale, I’m finally able to take a deep enough breath to figure out what I want to do.

Some hospitality workers might find a better, steadier, more humane and sustainable job in the industry. And some, as Reiner points out, might not return at all. Because the hospitality labor force, like so many in the educational and higher ed and non-profit and public service and childcare and health care labor force, isn’t just exhausted, or burnt out. They’re demoralized — which is different than being lazy or temporarily burnt out — and that was true even before the pandemic.

Demoralization is what unites the underpaid, pandemic-unemployed worker, the adequately-paid, Covid-essential worker, and the more-than-adequately-paid, WFH knowledge worker — the latter of which form of the core of Kevin Roose’s recent piece on “The YOLO Economy”:

“Some are abandoning cushy and stable jobs to start a new business, turn a side hustle into a full-time gig or finally work on that screenplay,” Roose writes. “Others are scoffing at their bosses’ return-to-office mandates and threatening to quit unless they’re allowed to work wherever and whenever they want. They are emboldened by rising vaccination rates and a recovering job market. Their bank accounts, fattened by a year of stay-at-home savings and soaring asset prices, have increased their risk appetites. And while some of them are just changing jobs, others are stepping off the career treadmill altogether.”

Like Roose, I’ve also heard from a dozens of knowledge workers who’ve held on to their jobs over the course of the pandemic and are now dramatically rethinking their futures. They’re quitting jobs, they’re moving across the country — and yes, they’re able to do so because of financial safety nets, accumulated before and during Covid.

But the majority of people I’ve heard from (generally unprompted, over email and in Twitter and Instagram DMs; this is what happens when you write a book about burnout) aren’t bored, as Roose writes, or finally opting to follow life-long passions. Their decisions are borne of exhausted despair, and don’t really feel like decisions at all — even as most acknowledge just how lucky they have been to have jobs over the past year, and, by extension, the financial security to leave them.

Some of these people left the workforce because they had no other childcare options. Some, like those I heard from for my piece on teacher demoralization, are taking early retirement. Others, like journalist Olivia Messer, featured in the NYT piece, as well as Stacy-Marie Ishmael, Millie Tran, and Megan Greenwell, have reached physical and mental breaking points (one of many reasons to donate to the therapy funds for AAPI Journalists and Black Journalists).

But again: these workers are not lazy or whimsical or seeking their bliss, and these moves aren’t quarter-life or mid-life crises, or something that a mandated one-week vacation will fix. These workers were, or are, on the verge of collapse — and have come to terms with the reality that something has to give. It won’t be their jobs. That leaves them.

I’m exhausted by all of these restaurants wondering why they can’t find workers — and I’m also exhausted by all of these corporations wondering why they can’t retain parents (and mothers in particular), why they can’t recruit (or retain) BIPOC workers with policies that stipulate that they have to live in Seattle or Portland, why their barely-paid internship program is so enduringly white, why their workers keep trying to unionize, why their invocations to “take some time if you need it” have been insufficient, why initial spikes of pandemic productivity has plateaued or declined.

In truth, this isn’t the YOLO Economy so much as the “Capitalism is Broken” Economy — with an accompanying “great reshuffling,” as my friend Michelle Legro dubbed it, facilitated by the safety nets of UI, student loan pauses, moving in with family members to facilitate care, and/or accumulated remote work savings.

The models up and down the American economy are unsustainable. They have been built on the belief that profit — and, in many cases, exponential growth — should, as a rule, supersede labor conditions. In ‘knowledge’ jobs, they have been guided by the false idols of productivity and workism; in the retail and hospitality industry, these conditions have been facilitated by anti-labor campaigns, perverse private equity imperatives, and lax (or non-existent) regulation of the gig economy.

The pandemic did not create these conditions. It simply made them even more impossible to ignore — and created scenarios in which some workers (not all, but some!) have been empowered, perhaps for the first time in their working lives, to opt out.

I want to be optimistic about the potential for a shift in these models. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned about American capitalism, it’s the skill and swiftness with which it translates resistance into personal, moral failure — which is precisely what so many of these business owners and politicians have done.

Refusing to prostrate yourself on the wheel of work is not a failure. Nor is it self-care — at least not in the narrow, individualistic way we conceive of it. It can be a means of advocating for yourself, but also your peers, your family, even your children. But here’s the thing about a reshuffle: you’re still playing with the same deck of cards, and the game of American capitalism is still rigged against the worker. Which is why business models in everything from tourism to early childhood care need to be fundamentally reconceived — and built in a way that doesn’t hinge on workers making poverty-level wages.

We should ask ourselves, our communities, and our government: if a business can’t pay a living wage, should it be a business? If it’s too expensive for businesses to provide healthcare for their workers, maybe we need to decouple it from employment? If childcare is a market failure, but we need childcare for the economy to work, how can the government build that infrastructure? If the pay you provide workers doesn’t allow them to live in the community, what needs to change? Collectively, we should be thinking of different funding models, different ownership scenarios, and different growth imperatives. Failure to do so is simply resigning ourselves to another round of this rigged game.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. Last week’s Friday Thread was on trying to hold the United States at arms’ length and explain it, and filled with gems and sorrow. The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

This post reminds me of BULLSHIT JOBS by David Graeber! The crux of the book is that UBI can tip the scale in power dynamics between employers and employees (which currently heavily favors employers in this age of decreasing unionization and little to no antitrust oversight) so that workers can take more risks with the career decisions and refuse to work "bullshit jobs."

I was wasting away at a "bullshit job" for years and quit right before the pandemic started. I somehow fortuitously qualified for unemployment benefits, and the checks were were more than what I made at the old job. Because of the benefits, I didn't take the next available job that paid just as badly and drained my soul. Instead, I took my time and eventually (10 months no less!) found a job that fits my skills and interests. More importantly, this new job pays me a living wage! I know I'm probably an outlier, but even with the stress that comes with being unemployed during the pandemic, this past year was truly a blessing in disguise for me. I think something like UBI in the after times would allow others to do the same and find work that they find meaningful and fulfilling. As always, thank you for your great insights!

I've been thinking a lot about this issue, as I watch businesses in our town struggle to hire staff. Interestingly, the employers that took care of their staff during Covid-19 (making environments as safe as they could, mandating masks, shutting down their businesses when there were Covid-19 outbreaks while staying paying people, etc.) are not having trouble hiring. I agree with your take that many are taking their time looking for work and looking for work that fits their particular needs. I live in Flagstaff which is tourism driven, and is also a college town. The lack of college labor, with students doing remote school has also been an issue. We have a $15 minimum wage, but we lack affordable housing. All of these factors are contributing to the struggles with finding help.

Personally, I work in healthcare as a behavioral health therapist. I worked in a hospital setting, and worked throughout the first year of Covid. I just quit my job because I'm emotionally exhausted. It's not the people I work with, it's not the patients...its administration that continues to try to solve new problems with old tools, the lack of support, and the complete disrespect and disregard of the community at large in the face of Covid-19. Flagstaff is fairly progressive and was really ahead of the game with regard to safety precautions, but the toxic political climate and the plethora of "muh rights" anti-maskers, just wore me out. I'm taking a year off to travel and decide what next steps are. I'm going to be 60 this year, and I know whatever I decide, it's going to suit my needs and work style, not someone else's.