Do you find yourself consistently opening these emails? Do you come back to them or forward them or think about them over the weeks to come? If you value the work here, if you send it to your friends or revisit it, consider subscribing.

You’ll get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, the ability to comment, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the stuff that adds value to your life.

Going back to your college for reunion weekend is an exercise in nostalgia. Some of it is straightforward — a glimpse into a freshman dorm room makes me feel like I’m back in the corner organizing my Winamp playlist — but a lot of it is comparative. These kids don’t party like we did, these kids’ dorms are so much nicer, these kids are always on their phones. Every five years, the students have seemed more serious, more “studious,” less present.

I’m sure my class of students felt that way to visiting alumni, too. But I also think we left college at a genuine pivot point: in 2003, when we graduated, a handful of people had cell phones used exclusively to call home; the next year, the vast majority of the incoming class of freshmen arrived with them.

We prided ourselves on being a school full of kids who worked hard and played hard — drinking, sure, but also a deep investment in intramural football (particularly for women), a very liberal-arts amount of ultimate frisbee, and buckets of traditions and costume parties, including an all-campus chorale concert and the unofficial but administratively tolerated “beer mile,” when students would run naked or in costume around the green at midnight on Reading Day.

In hindsight, much of this play was facilitated by various privileges, first and foremost the institution’s capacity to insulate students from police surveillance and, by extension, criminal records. But we also played in different ways: with words in creative writing seminars, with iMovie in beginning filmmaking, with satire in the college newspaper. It’s corny but true: college can be an intellectual playground, the rare space where you can try on ideas and personality traits and try out ideological tools and see which ones fit you.

There are parts of my college experience I would do differently, but I don’t regret the way I split my time between study and the college version of play. I also recognize how the basic set-up of our college experience made that divide much easier to manage. We had AIM, and we checked our email every few hours, but if you were sitting at a table in the library, you were doing neither. Doing your reading meant generally reading from an actual book. The biggest distraction on a Monday night at the library was just other people, walking around and talking to you.

Part of the reason we had more time to play was because completing our actual work took less time. Not because we were smarter, but because we had fewer addictive sources of competition for our attention. Sometimes I would feel the crush of juggling three papers all due the same week; sometimes, particularly freshman year, I felt lonely and heartbroken and discombobulated by failing at the thing I thought was my thing. But after years in a hometown where my primary task was constantly sanding down the rough corners of my weirdness, college felt like a gift. It was a gift.

And part of that gift was protest. My freshman year, a student accused of sexual assault forced a campus-wide discussion on how the college should be handling these cases, what it owes to survivors, and whether suspension was sufficient. I remember sitting quietly in the back of a protest on the campus quad — awkward and listening. I watched the planes hit the Twin Towers from a television in the writing center and remembered how difficult it was for faculty to figure out how and when to teach in the aftermath. We were timezones away, but the grief hung in the air for months.

There were anti-Iraq War protests on campus throughout the spring of the following year. My ex-boyfriend, who was later killed in the war, was stationed in the DMZ in North Korea. I was getting ready to graduate and I was also trying to figure out how to feel, what my politics and loyalties actually were and where they would lead me. It wasn’t a distraction or an indulgence. It was life.

I was better equipped to process these moments and movements because I had the space and time and freedom to grapple with them. I was always studying and always playing but I somehow was also always hanging out in my own brain, for better or worse. There was no phone to make it all feel easier or more understandable, even if it wasn’t.

I’ve been thinking about my experience this week, and the failure to acknowledge just how little of that same space and grace we’ve created for this current class of students. I’ve read dozens of pieces on the protests against the Israeli war on Palestine on campuses across the United States; the best, like this piece from Lydia Polgreen, include significant time on the ground doing actual reporting: both talking to protesters and working to discern who’s part of the protest and who’s an anti-Semitic crank shouting on the corner.

But there are also pieces — like this one from the Wall Street Journal, titled “They Entered College in Isolation and Leave Among Protests: The Class That Missed Out on Fun” — that situate the protests as a depressing bookend to a ruined college experience.

It’s a long feature, written by the Journal’s higher ed correspondent, and synthesizes interviews with students, statistics on student loneliness and time use, and conversations with faculty about “the great disengagement” they’ve observed amongst this particular cohort of students.

The conclusion: “College students today are lonelier, less resilient and more disengaged than their predecessors, research shows. The university communities they populate are socially fragmented, diminished and less vibrant. The pandemic bruised the psyche of a generation. The politics seared it.”

Students feel like they’ve never had a chance to be “kids” in college:

“We’ve never had a calm time when we can just focus on being kids,” said Tejasri Vijayakumar, a senior and student body president of Columbia College at Columbia University. “You talk to people in generations above us about college and they said you could just gather in spaces and do whatever you want and no one would stop you, that’s not really true anymore.”

And faculty feel like the overall campus vibe is less, well, collegial:

Despite the current protests on some campuses, in recent years college quads have lost their “town square” feeling. There are fewer crowds. Less excitement. Smaller knots of students in conversation or enjoying free time with friends on the grass.

“How can I put this, it’s duller than before Covid,” said Gari Laguardia, who has taught Spanish and culture at SUNY Purchase for nearly 40 years. “The kids are less independent than they used to be. They seem to not be able to exercise much agency.”

And students are spending much more time in their rooms:

Libraries and other academic study areas have significantly less foot traffic than before the pandemic, and students are spending more time in their dorms and less time in gyms and fitness areas, said Aaron Benz, CEO of Degree Analytics, a Texas-based company which measures where students spend their time on campus using the school’s wireless network. […]

University cafeterias at some schools, once universal gathering spots for students, now mostly serve students with bagged lunches they take back to their rooms to eat.

The average student is spending 40% less time in dining spaces than before the pandemic, said Benz.

“The data also suggests students are spending more time alone in their dorm rooms,” said Benz.

And if the headline wasn’t a tell re: the attitude of this piece, the kicker certainly is:

Orly Meyer is the class president at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. She said a lot of institutional knowledge within student clubs was lost during the pandemic.

One such tradition was a walk members of the student government would take as a group before a meeting. After Covid, someone brought a rope. And now they walk connected, like a group of preschoolers, she said.

“It’s nice,” Meyer said. “It’s something we all do together.”

The infantilization is striking, but it’s also the point: readers of the Wall Street Journal already think this generation is a bunch of anxiety-riddled babies; this piece simply confirms that colleges are making it worse. They indulge students’ worst tendencies. They make them pack lunches. They hire WELLNESS COORDINATORS.

The piece gives scant attention to the sources of all this isolation, social anxiety, and disengagement. Instead, it glosses over stark realities: like how one might be expected to process a weird, un-cathartic conclusion to their high school years while also trying to protect themselves and their loved ones from a deadly and poorly understood disease while the adults in their lives argued over whether wearing a mask was un-American.

It’s worth remembering: some of these students ended up on campus in the fall of 2020, but others had to start college from their bedrooms, on zoom, still terrified. When they did return to campus, it was to a quasi-surveillance state, with well-meaning but often arbitrary rules about how many people could gather and for what — and where they learned that the best way to keep healthy and out of trouble was to hang out by yourself in your room. They studied (but couldn’t go the library or change the scenery); they sought versions of play online; they burned out the same way so many of us did, their hours marked by switching from smaller screen to slightly larger ones.

How did you feel in the fall of 2020? I was struggling mightily to concentrate on anything. And I had the benefit of figuring out how to best concentrate for twenty years! And here these students were, experiencing their first college lectures over zoom — or, in semesters to come, trying to hear and communicate with classmates through masks. They had to find new ways of creating intimacy and community and fun, and how to fall in love, or how to even figure out what they love. They had to take care of themselves and each other. And they did it under significant, prolonged duress, with very little grace extended their way.

When institutions did extend grace — providing the sort of mental health services that save lives, or accommodations for students battling their own anxiety — it became evidence that college was the source of the problem, instead of the backdrop for it.

There’s been so much hand-wringing about the current state of students, the source of all this disengagement, the causes of such sustained “learning loss.” The answer has always been right fucking there. It’s the grief, assholes! Grief for their weird high school graduations, of course, and for the family members they lost, and the college experience they imagined. But they’re grieving their inherited reality. I find people will name it, the same way they’ll name a hurricane, without actually acknowledging its force — as if you could separate the storm from the devastation it caused.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have talked about what is going to happen to all this deferred grief, all this swallowed loss and unprocessed trauma. The result is all around us: in the disengagement from politics, in the loss of faith in public institutions, and in the waves of people fleeing professions on fire. It’s in the wages of our ruthless economy: the growing encampments of people with nowhere else to go, the bodies breaking because they can’t find or afford the care they need.

And it’s in the lives of our college students, who, despite the reporting in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere, actually attend colleges all over the country, with all sorts of on- and off-campus living situations. Less than half of college students graduate in four years, further complicating the four-year no-fun college experience thesis.

But even if they don’t go to a university like Columbia or a liberal arts college like mine, they have become adults amidst continual societal convulsions, with very little space for contemplation or processing. Other young adults have lived through seismic wars and mass protests. But they also didn’t have to do it with mini-computers in their pockets.

So if these students are “less resilient,” it’s not because they’re not resilient — it’s because they were forced to expend so much of that resiliency over the last five years. But even that framing smells of bullshit. Here is a micro-generation that, if we’re to listen to the commentariat, is detached and anti-social thanks to smartphones and disillusioned by coming of age in the middle of multiple economic, social, political, and viral disruptions. By that logic, these students should be removed from the world to the point of nihilism. But what we’re seeing in these protests is the near opposite. It’s not nihilism. It’s activism.

These protests aren’t taking place on forums or social media; they’re happening in physical space. It’s not a disengagement from a world that has largely left them to fend for themselves; it’s a brave, angry, and frequently messy engagement. I look at the protests and see students funneling their grief in a way that disrupts the narrative of their own disengagement. And I see them using the tools they were given to fend for themselves during the pandemic — the surgical mask — to fight surveillance. I see adults, not children, furious about the inhumane Israeli assault on Palestine, and advocating for their institutions’ disinvestment in that war. If you listen closely, they’re also mad, and righteously so, about so much else — including the idea that peacefully protesting is “ruining” their college experience.

College is about learning how to learn. It’s also an education, as Hamilton Nolan puts it, in bullshit: in how an institution, or a workplace, or a boss can profess one belief and govern in a way that utterly compromises it. I hope students see the headlines about their college experience and understand them for what they are: attempts to trivialize righteous anger and grief, of course, but also a displacement of shame. There is so much we older adults could’ve done to make these students’ lives more survivable — during the pandemic, sure, but also over the course of the last two decades. We did not. Blaming them comes so much easier than blaming ourselves. ●

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. You can find all previous threads here, if you need that enticement.

Culture Study is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

Plus! Subscribing is how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. It’s also a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

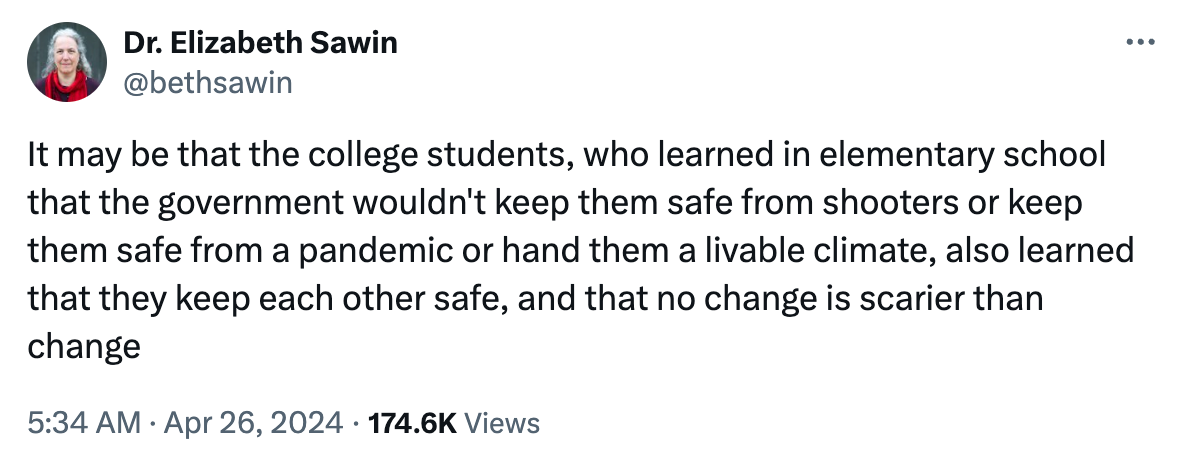

One of the powerful things I come away from this excellent piece with is that actually these protests are a sign of resilience -- they're college students doing a very classic college student thing despite all of the wailing about how these kids are different and weaker. And they're doing it over something that is a common thread in so many of the biggest and most famous student protest movements of recent decades: the idea that some people's humanity matters less than others.

FWIW as Columbia students take over a building, I'm remembering a time when I was a kid and my father took me with him to deliver pizza to students who had taken over a building at UMass, where he taught. I don't remember what that protest was about, but it stands out that he 1) was able to approach the building with pizza and send it in and 2) felt safe bringing his kid because there was no thought that police in riot gear were about to storm the place.

Thank you thank you thank you! I'd love to read a companion piece on how corporate-style university leadership and relentless focus on assessment and outcomes is augmenting these problems. I work in public higher education and the shift to metrics Metrics METRICS--often from those who are quite removed from the classroom--has also played into the despair students are experiencing. They can't just come to an event and connect and enjoy it. They have to perform that they learned something with an assessment and exit survey. They know that they are data, not just to apps but also to their schools.