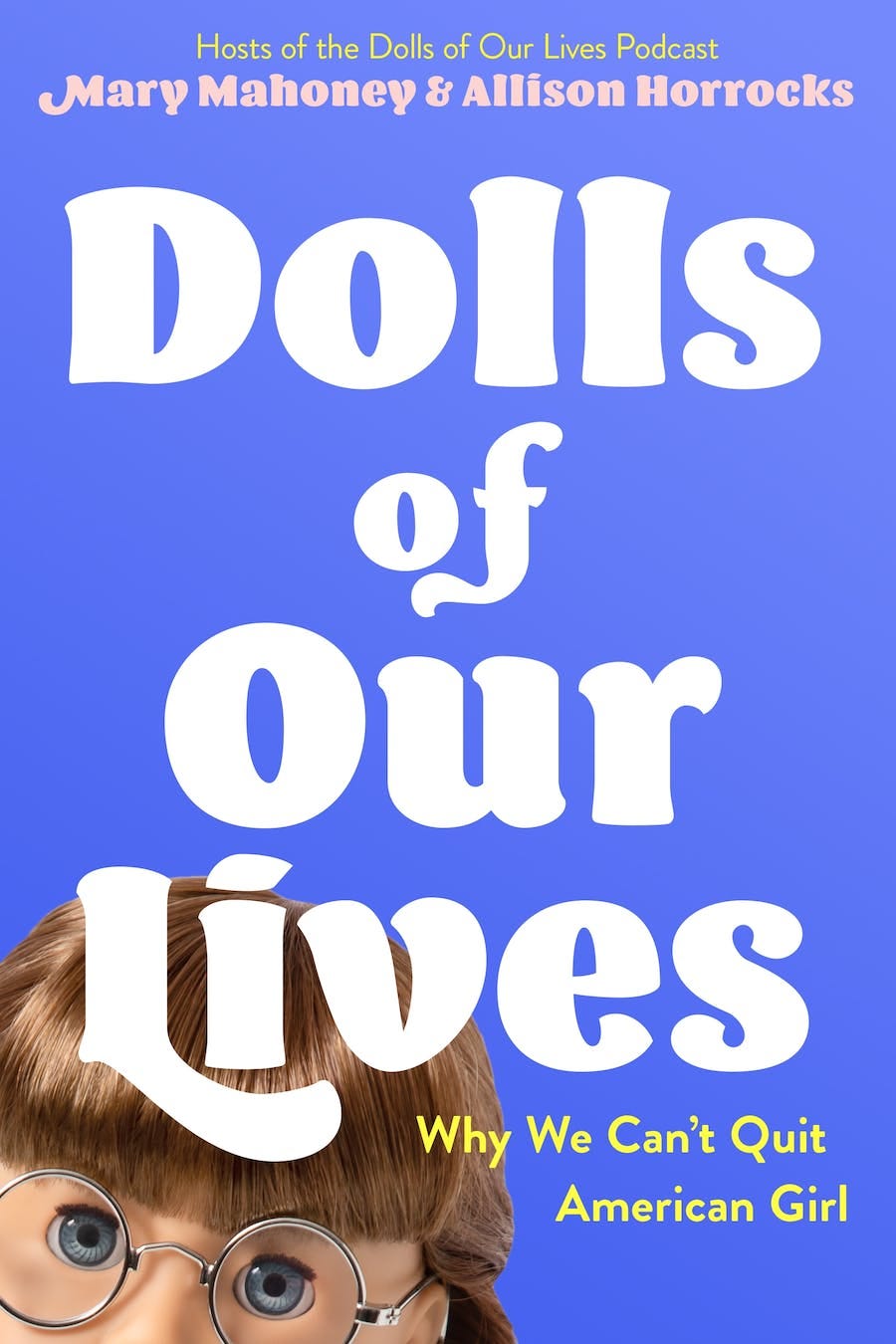

The Dolls of Our Lives

A truly fascinating discussion of all things American Girl Doll

Nearly four years ago, I unearthed a picture of me from a Christmas long ago. I was wearing a “Christmas dress” — picked out with great care the weeks before — a “Christmas headband” (that absolutely hurt my head during Christmas Eve service) and poorly applied bright red lipstick (my mom sung in the choir, so she’d leave our house early — and I somehow must’ve convinced my dad to let me wear my favorite shade of lipstick from my mom’s drawer).

In my arms was the much-anticipated already-beloved gift of the night: a Samantha Doll, chosen from the American Girl catalog that I had poured over nightly in the months preceding Christmas. It was from my Great Aunt Bernie, who’d never had children and whose husband had died a decade before. She was an eldest daughter who brought her family through the Depression, and when she died, many years later, they found stacks of bed sheets, dating to the 1970s, never used but purchased because they were a bargain. (We knew they were a bargain, of course, because the clearance price tags were still affixed).

American Girl Dolls were not a bargain. But my Great Aunt Bernie chose to hunt bargains elsewhere and use that money on me and her other grand-nieces and nephews. In hindsight, it was a wonder, and I wish I could’ve played with her and the doll more. But for many reasons, many of them dating back to those bare Depression years on a dairy farm in Southern Minnesota, she was never a playful person. I wrote her bright thank you letters, and loved to sit and do puzzles with her when she’d come from Minnesota to visit alongside her younger sister, my Grandma Helen, who didn’t have the money to buy me a doll but did have the skills and ingenuity to sew me a full set of linens for Samantha’s brass bed, which she bought for a steal at a non-American Girls doll company.

American Girl Dolls leave a trail a stories behind them. Stories of desire and jealousy — they are not and have never been cheap — but also stories of family and identification. They themselves are rich texts (how can a doll with a whole six-volume backstory intended to explain what it was like to be a girl in a certain time period not be). But the way we talk about them — that’s a rich text, too.

The first time I listened to the Dolls of Our Lives podcast (then called the American Girl Podcast) I felt a surge of delight. The hosts, both historians, were thinking expansively and seriously (and sometimes unseriously) about these dolls and their place in the millennial imagination — but also exploring and interrogating how the series thinks about whiteness, and colonial expansion, and class, and gender expression, and who had access to these dolls and their narratives….and so much more. Plus — and I really want to emphasize this — it was deeply, deeply funny.

A book off-shoot of a podcast is hard to get right, but if anyone could do it, it was two very funny and very smart historians. I hope our conversation below gives you a sense of just how good this book is — and what a perfect gift it would make for anyone in your life (including yourself) who has an American Girl story.

You can find Dolls of Our Lives: Why We Can’t Quit American Girl here and find the podcast (and a whole lot more about Mary and Allison) here.

For people who aren’t familiar with the podcast, let’s talk about your (sorry incoming academic word) *positionality* when it comes to American Girls. How do you relate to them personally, and how have you found the podcast and book relates to them, and why is it important that you’re both Mollys?

Mary: I have always felt like a Molly, even long after I’d forgotten the plots of all of her books. When I was a kid, Molly was my favorite because her stories connected me to my grandmother who had lived during Molly’s lifetime. Her books became a bridge for us to share stories about ourselves with each other. I think, looking back, I was also drawn to Molly because some part of me read her as queer.

Though I didn’t identify that way for a few years, I felt an affinity for her jeans/saddle shoes/plaid shirt lifestyle. As someone who was never particularly drawn to feminine clothes, her world felt like a place I could live comfortably (though it was not a safe moment for gay people generally during the World War II era). When I met Allison, it mattered that we were both Mollys in the ways shared pop culture interests can serve as immediate points of connection and conversation. It felt like sharing your zodiac sign: it seemed to suggest some traits in common (glasses, pluck, lack of attention to details), without a basis in any kind of hard science.

The premise of our show was a frankly selfish desire to revisit books we knew had meant a lot to us though we could not recall details of the books at all. We’d become friends in grad school and the idea for the show was a kind of gift to ourselves for finishing. When I’d started my program, someone teased me for citing American Girl as a childhood inspiration for pursuing an interest in History. We’d had similar moments in those years of having our interests demeaned because they didn’t appear overly academic or ground each intellectual commitment in a monograph we’d read.

When we made the show, it was originally with ourselves in mind. We lived in different states and wanted a biweekly excuse to talk about something that had meant a lot to the both of us, without embarrassment. We settled on rereading one book per episode to give us something manageable to tackle each episode, as we’d take on the plot, the history of its setting, and of its publication.

As historians, we were curious about the ways the books might reflect more of the years in which they’d been written than the years they claimed to represent. Would Molly’s World War II stories reflect a Tom Hanks’ style embrace of what Tom Brokaw called “the greatest generation,” for example? (Yes.) For ourselves, we wanted to know if the books lived up to our own strong internal hype.

We purposefully begin each episode with a brief recap of recent pop culture we enjoyed to bring people in to later conversations about history. There is so much imposter syndrome around discussing certain subjects or a perceived aversion to things we were perhaps taught in a way that never felt personal. Many people think of history as memorizing trivia, for example, and hated it in school. I think of history as the way people organized their worlds and their place within them. It’s something to think with not content to know.

By thinking with history of different eras (even 9-year-old girls in American history), we can reimagine how we think about our own histories and how we organize our worlds and place within it today. Not to get too soap boxy here, but I think this is a vital skill in an era when the humanities are being downgraded because we can’t get you a job in STEM.

We started with pop culture talk not only because we’re two friends catching up on things in our lives (of which pop culture is a big part), but because we’re hoping that if listeners come along for that ride they will also join us for the history part as another area of possible new interest. (Not for nothing, but talking about how we think about Britney Spears is one revealing way of understanding how we organize our worlds and women’s place within it.)

Don’t be fooled into thinking our podcast was a project to save the humanities (or Molly’s reputation). At our core, we just wanted to spend time with Molly again and see if it still resonated, even from the distance of adulthood. The grad school teasing was an important moment in the back of our minds as we made the show. We wanted to invite people in to revisit the books and brand with us, and not demean the things of childhood that mattered to us.

There is a world of difference between writing off an interest as childish and realizing the weight of things that touch us in childhood. We wanted to maintain that enthusiasm while also bringing a more critical fandom to it. Yes, we loved American Girl (Molly and the magazine were so big for me) and some of the choices haven’t always aged well (Hello, Felicity, girl from a family claiming ownership of enslaved people who desperately tries to liberate. . . a horse?)

We brought this same eye to our girl Molly whose books never mention the Holocaust and whose wartime privations feel pretty minor considering Molly’s privilege. This is not to say we still don’t cherish what Molly has meant to us, but our fandom is able to sit with the complexity of good will, tough questions, and ultimately challenges to do better. We have listeners who write in to let us know that they don’t identify as Mollys and we can hear that. What defines our show is not that we’re both Mollys (though that bias is there), it’s that we’re both capable of complicated fandom that can handle both the highs and lows of the brand.

When we set out to write our book, we wanted to go beyond our stories with American Girl or our historical interpretations of each book (all of which are available in our back catalog). Instead, we wanted to capture a sense of what inspired the brand and what it’s meant to generations of fans. This meant representing the stories of people whose lives look very different from ours and whose affinities for different characters range the entire scope of the AG offerings.

Allison: I was a very big fan of all things American Girl when I was young (starting around age 8). That phase of my life lasted for a few years. I eventually phased out of collecting dolls and put my American Girl collection away in a trunk. When I was first deep into AG, I was privileged enough to have a number of dolls as well as accessories. Some were homemade and others came from the catalogue. I also proudly displayed my American Girl books for years. I thought they always looked so refined and I loved seeing the series I could complete while working my way through the AG universe.

As an adult, I returned to American Girl partially out of curiosity. I wanted to see what had fascinated me so much in the past and if there was more there there to unpack. It was also a great way to connect with people while studying History professionally.

In terms of specific characters, I've felt some kind of affection for Molly McIntire since 1995. As an adult, saying "I'm a Molly" to the right kind of audience conveys a number of things right off the bat. I used to want to look like Molly, and now I sometimes find myself in a thick argyle sweater wearing my glasses.

We chose to make the phrase "Run by Two Mollys" an early tagline for the podcast. Many people would have no clue what this meant. But we suspected a good number of possible listeners would know right away. We have often been critical of American Girl. For me, that little line is a reminder that we are also still fans on a number of levels. Our goal has never been to study American Girl from a very distant or strictly intellectual remove.

Can we talk a little about Pleasant Company → Mattel and how it affected everything from the marketing to the fabrication of the dolls? I think a lot of people aren’t super familiar with what happened, or how Pleasant actually positioned itself, in your words, as a “lifestyle brand” ripe for acquisition.

Mary: I would love to paint a picture of American Girl’s pivot from its original fixation on girlhood in history to its lifestyle brand era as something Gwyneth Paltrow could relate to on a similar Shakespeare in Love to Goop trajectory. However, can anyone possibly match the complexity of that rebrand?

What largely defines this story is the perception that Pleasant betrayed her own vision by selling her anti-Barbie brand to Mattel, the home of Barbie. When she’d first designed her line of dolls and books, she was driven by a desire to create dolls and stories with real meaning, in other words, not the Cabbage Patch Dolls she thought were “ugly” or the Barbies that encouraged girls to grow up too soon, all of which you’d find at Toys-R-Us, the very neon lights of which she found “offensive.”

This desire to create toys with meaning and educational value was inspired in part by her professional experience. She’d started out as a teacher, then become a tv news anchor, and then become an educational entrepreneur launching a literacy program. When some of the earliest profiles on Pleasant appeared in newspapers in the 1970s, she remarked on what she saw as a generational divide in society. “We live in a dehumanized world much of which lacks real meaning,” she told a reporter in one 1970 profile. “Youth is frustrated by the hypocrisy they see in the establishment and the world around them in general.”

In a post-Watergate and Vietnam world, Pleasant was one of many who felt what kids needed was a strong sense of morality and patriotism. She also believed in feminism, sort of. She wanted equal pay, but didn’t like that the movement seemed to “de-emphasize the basic femininity of women,” adding, “The feminist movement defeats itself when it pounds the table and puts on army boots.”

With this in mind, we can see her invention of American Girl as an attempt both to restore a sense of meaning to traditional institutions like girlhood, the family, and the nation that is not out of place with Reagan’s rise to prominence citing similar nostalgia for “traditional” American patriotism and values.

However, perhaps of less importance to Reagan, Pleasant also wanted to empower girls at the center of historical narratives as characters with real agency in the lives of their peers and community. These girls were always going to be girls, never growing up too soon. They would love their parents and do . . . something for their country. What Kirsten did for America is an open question. What America did to her is more entertaining to consider. (She sold fur pelts she took from a dead man in a cave to save her family. Is this the legacy of free enterprise?)

The transition to tell stories about girls in the present and to present a range of products for girls in the ‘90s was not to abandon her historical project, but to extend her main goal: to speak to girls and offer them books, a magazine, dolls, and other treats that enshrined girlhood as a timeless value. Perhaps the girls of today or the girls that looked like you weren’t exploring historical moments (except perhaps the history of eugenics), but they did still abide by her intention to celebrate girls without inviting them to grow up too soon or to define themselves by their interest in boys, make-up, or other age-inappropriate interests.

When she launched Felicity at Colonial Williamsburg in 1991, she gave a speech captured by an attendee and now preserved on YouTube where she lays out her dreams for the brand. Rather than talk about the importance of teaching history or educating girls on patriotism, the thing she values most is a generational vision for the brand where mothers and daughters would share in the dolls and books and then continue to pass them down. If she was focused on anything, it was this matrilineal idea of inheritance that would preserve this timeless vision of girlhood.

With this in mind, the transition to a “lifestyle” brand model that offered far more than history-based dolls and books was not a betrayal of her brand, but an extension of this celebration of a particular kind of girlhood (often white, middle-classed, patriotic) into the present. The magazine is a great example of this. It initially offered short stories drawing on the historical characters, but within a few years evolved away from that to focus entirely on the present. It invited girls to offer advice on a range of topics and to seek advice in the Help! Column, celebrated their matrilineal family histories in the form of paper dolls based on actual girls, and featured all kinds of content that spoke to girls and their lives today.

Allison: We get asked this question a lot. I think people are curious about how the brand changed in the mid-1990s. They especially want to see a change around the time that the Pleasant Company is acquired by Mattel, in 1997.

There are some clues as to the evolution of American Girl that can be located in the early 1990s. I see Pleasant Rowland as a very ambitious businessperson who also cared about education. That order of priorities is useful in considering the brand she built and how she sought to market it to consumers. This was never a non-profit, purely educational enterprise. This is a line of products coming out of the excesses and cultural panics of the 1980s.

With some early success, I imagine that people running the company saw the potential in even denser marketing around the characters. They also suspected, rightfully, that they could be useful to girls in terms of contemporary problems. That's the genesis for everything from the Giggle Books to the magazine and the line of "modern" 1990s merchandise, like the varsity jacket. I think that the creators within the world of Pleasant Company and American Girl were right to take young people's concerns and problems seriously. They did well because they also convinced people with access to the money to buy these products that this was a worthwhile investment.

The role of the dolls in friendship is a through line of the book — it’s at the heart of how you relate to each other, but you’ve also found it at the heart of so many others’ stories about the dolls. The dolls help us relate to people (I love the story of Mary, her Molly, and her Irish grandma, for example). Can you talk a little more about how you’ve seen this manifest in your conversations and analysis, why it matters, and your thinking on how friendship around a bourgeois object can work as a sort of de facto class sorting mechanism?

Mary: In practice, the American Girl dolls make friendship happen by presenting shared topics for conversation. Which doll is your favorite? Whose books did you like the most? Which character’s clothes would you most want to order from the iconic catalog?

We’ve heard from fans of the brand who have developed lifelong friendships with their dolls as a kind of connecting mechanism. Playdates with American Girl dolls created opportunities to bond over all sorts of things, for example. The brand also helpfully (and profitably) offered guides for just these kinds of occasions, including birthday party planning ideas and sleepover guides. We’ve heard from other fans who made friends using the Magazine’s pen pal program which matched girls up with a pen pal their age. Interviewing Kat Dennings recently on our show, we learned she took part in that program and even attended her pen pal’s bat mitzvah IRL because they’d developed such a strong bond beginning with this American Girl program.

Every American Girl has a best friend or group of friends, and it’s clear that friendship really matters as an essential part of their lives. Addy’s friend Sarah helps her navigate school and the many changes of life post self-liberation, for example. Samantha, a privileged Victorian girl/ labor activist who definitely did not die on the Titanic learns a lot from her friend Nellie, a girl from a different class background. Her embrace of a savior complex in the pursuit of helping Nellie and her sisters, though genuine in intention, invited conversations for us about the importance of acknowledging different family histories with money and current financial realities in adult friendships. Though that may not have been the intention of author Valerie Tripp (I doubt she imagined adult childless women would be reading the books and mining them for conversations about a whole host of things), it offered us an entry point to the link between money in friendship both among kids aspiring to own the dolls and adults reflecting back on these expensive objects of affection.

We’ve heard from many adult fans who never owned a doll because their families couldn’t afford it. This is an ongoing issue with the brand that they have done little to address. When the dolls were first launched, Pleasant herself likened the expense to a Nintendo or game console, as if that seemed to put its high cost in context. It’s like she compared buying a tiny home to buying a McMansion, as if privilege can be understood by degree by those who lack the ability to buy at all. For some girls, this desire for a doll led to their family’s first open conversation about money and budgeting. For others, it became a wish they’d harbor into adulthood when they had their own money to fulfill that childhood wish.

One girl wrote us that she really wanted a Kirsten doll, but couldn’t have one. Her neighbor had one, and she really wanted to play with it. The neighbor said no, but let her flip through her catalog. This example has stayed with me so much because sharing the catalog seems more cruel than not sharing anything at all. Was it meant to be a consolation prize? Or a distraction from the choice not to share the very thing this girl wanted, but could not have. These kinds of moments demonstrate that rather than place girls in the center of the story, as the brand intended, its cost could push girls without the buying power to consume its products to the side in social settings like AG birthday parties or playdates.

Allison: Some people felt alienated in conversations about American Girl years ago, as children. A number of people still feel alienated now. The cost of these products is a barrier to entry, full stop. Even the fact that one can get and borrow dolls at the library does not solve that problem.

One need only look at comments sections on any article about the dolls to see consistent criticisms of the cost. While one person might think they have missed out on a formative experience, for others, the pricetag is just proof this was never meant for them anyway. There are also folks who have never owned a THING made by this company who are deeply devoted to its legacy. For some people, the catalogue was their primary and only entry point into engagement with the brand. I think that would disappoint but not shock the founders of Pleasant Company. Rowland imagined that these dolls would be heirloom quality. Many of them have held up well enough that people of our generation can pass them along to family members and/or loved ones. A finely crafted product is never cheap. However, I also think some small amount of the backlash against products such as American Girl comes from the fact that families and adults are choosing to invest money into the pastimes of children (and let’s be honest, usually, girls).

With the original dolls, I feel like there’s a real sorting mechanism at work: like, my friend is a total Molly, and I could’ve told you that way before I knew she had a Molly, and my other friend is an absolute no-question Samantha. It’s not dissimilar to Sex and the City character identification or Harry Potter house sorting. There’s something psychologically complex happening in these identifications — it’s a way to understand yourself and others, albeit a pretty flat one.

So what happened (and continues to happen) as the array of dolls expands? Is there still a broader typology? How does the marketing of these dolls encourage or discourage cross-racial identification? And oh my god how do the dolls that you can create to look just like you trouble this entire enterprise?

Mary: It’s kind of wild to consider whether the “just like us” dolls are a low-key effort to remind us all that eugenics was created in the United States. While the original dolls were entirely white (apart from Addy; and we can consider what it means to offer the first black doll as a formerly enslaved person mostly white consumers are invited to buy), the “just for us” were a step towards more inclusive mapping of girl onto doll. In the wake of very legitimate criticism that the historical dolls were overwhelming white, the brand also introduced more historical dolls of color including Josefina (1997), Kaya (2002), Cecile (2011), Melody (2016), Nanea (2017), and, most recently, Claudie in 2022.

What’s interesting about thinking through the sorting mechanism of the dolls and how greater attempts at physical inclusivity have or have not changed that self-sorting process is that even the consideration of this makes me feel like a person who dropped out of therapy/theological/medical school after the orientation powerpoint. Can I separate mind from body? Are we Molly’s by nature or nurture? Am I allowed to feel spiritually connected to a character whose only commonality with me is a perceived similar personality? These are all weighty questions that don’t seem to be holding back anyone on the internet where I’ve done some informal analysis of the personality mapping at work.

Though the brand has introduced many more characters beyond the first five (Molly, Samantha, Kirsten, Felicity, Addy), most of the memes online that talk about “types” play on associations with the original girls. I can’t tell if this is because the brand was at its most popular around these years, and the generations of fans for whom it mattered know them by heart or because I’m being profiled by an algorithm which once defined me as “middle-aged” (lawsuit pending).

I think the greater inclusivity of the later historical dolls and the “just for us” dolls has presented fans with more than the Rorschach test offered by the original dolls for early fans. Instead of offering a core canon of American Girl for fans to draw on for their own creation stories, the newer dolls allow a kind of DIY energy that feels more zine than bible. Fans can pick and choose from dolls and accessories to build characters entirely of their own invention (with whom they may or may not identify) or create tributes to historical girls and women the brand has not featured. Put another way, I may identify as a Molly based purely on the characterization offered in the books by Valerie Tripp. However, a younger or different fan may have grown up thinking of the brand as a Rainbow Rowell, using its component parts to write their own fan fiction that better suited them.

Allison: Some of the early marketing on the custom dolls feel like they are ripped from the pages of a eugenics handbook. Like with books, dolls (and really all toys) can be mirrors and windows. This emphasis on modern looking dolls came at a time when I was becoming less interested in dolls overall. What kept me tied to the brand was my interest in the stories and worldbuilding I could do with the characters I cherished. I have also met many people who are absolutely so proud of the custom doll they’ve created. We ought to honor that as a special act of creativity, even if some of the brand’s marketing around it was frankly, weird.

There have been a lot of hard conversations on various internet platforms among creators, especially in recent years. A lot of people show a willingness to see other perspectives or to change an idea they once had about their dolls. I have also seen an even greater awareness about the appropriateness of language. To say that one owns an Addy doll is both factually correct and uncomfortable when acknowledging that Addy's backstory includes her self-liberation. Educators who choose to spend their time to share their wealth of knowledge with others should be applauded; it’s not easy work. There’s also been more conversations among white collectors that this is work people need to do on their own, as to not burden people already dealing with systemic problems outside of AG collecting.

For people who think "it's just a doll," it’s never just about the doll. The world of American Girl reminds us that the things we choose to own and to play with say something greater about us. This doesn’t mean that we need to be reductive or constantly chiding people just because they choose to be a Kirsten (that was just an example, Kirstens, we love you). I never had any dolls that looked like me by design (though I hoped to look like Molly, which is maybe a fact that someone much smarter than me can unpack).

How do you see the dolls fitting into the ‘girl power’ postfeminist “consuming is feminist” moment? I find it fascinating the ways that the original dolls’ texts all seem to be pretty unabashedly nationalist (bordering on jingoistic!) whose “good citizenship” is achieved through thrift and thoughtful (limited) purchases….and the way contemporary girls can achieve that same level of good citizenship is through, well, buying more doll nightgowns.

Mary: American Girl is as feminist as the “this is what a feminist looks like” t-shirt, minus the willingness to use the word “feminism.” (We’re in the midst of reading the Julie books on our show, and I’m amazed at the reticence to use that word even in the “Peek into the Past” section in the back that offers historical context for the 1970s-era books. All in a story about the importance of title IX and other gender-related changes in the decade no less!)

The brand loved to make us feel good about being a girl. Beyond the stories themselves, they offered gems like the American Girl Magazine (RIP) which in 2000 counted down “100 Great Things About Being A Girl,” including Rosie O’Donnell (#74) and Girl Power! (#1). The feminist bonafides of the brand may be as impossible to unpack as that list, but I’ll offer a few thoughts.

Toni Morrison once tracked the trajectory of her lifetime as defining Americans first as “citizens” and then “consumers.” American Girl suggested that the two roles were inexorably linked. Molly’s dad is serving overseas during World War II and still somehow manages to buy her a doll for Christmas, for example. Talk about pressure. The Spice Girls, like their American Girl counterparts, were also savvy marketers and it seemed natural to us then that part of what fueled girl power was our purchasing power.

After all, we learned about girl power and all the things that were great about being a girl in a magazine we could subscribe to. Each character’s series had a moment when a girl received a doll inspiring us to then dream of a doll of our own. What’s surprising to me is the ways that the related “consuming is feminist” ethos persists. I think of this as I watch Tiktok videos, a platform that is increasingly feeling like QVC with the advent of the Tiktok store. Influencers will opine on the insights they learned about gender and self-care from a recently published book and add, “link in bio.” This isn’t inherently bad, but invites me to think about the other values of feminism we might privilege instead, like frustration and desire. Frustration at a system that trains us to want everything while presenting so many obstacles to ownership.

Allison: We’ve given a lot of thought to how feminism was marketed and sold to us as kids. I can remember listening to my SPICE girls CD and really feeling like these women were onto something. I ended up picking Sporty because her clothes looked most comfortable. I don’t know that this is an endorsement of 1990s feminism, but it’s not a clean cut indictment either. It was good for me to hear people boosting women at a time when women and girls on TV were often just punchlines. I also remember working really hard to get people to buy T-shirts with whales and other endangered species on them as a kid. I felt like that was doing something for the planet and I was proud of it.

Now, it’s common to hear millennials say there is no ethical consumption under capitalism, which feels both entirely true and defeatist, frankly. We are more than the sum of the things that we buy or collect. We are also much more than consumers. The desire and instinct to criticize my country is something stoked by American Girl, not by my middle school history education. I value that, even if it’s something that was being marketed to me. ●

We’d love to have Mary and Allison come on the Culture Study Podcast to talk more about *YOUR* American Girls questions — but we need you to submit them to make that happen. Here’s the very easy form where you can make that happen.

You can find Dolls of Our Lives: Why We Can’t Quit American Girl here and find the podcast (and a whole lot more about Mary and Allison) here.

As a girl, I always wanted Felicity. She had red hair and green eyes like me, and I loved that her time period was the longest-ago. I obsessed, for years, over every scrap of worn catalogs. I owned all her books but we could never afford the doll-- I grew up neglected in an alcoholic household. Decades later, when I found out I was pregnant with my daughter, I looked Felicity up on eBay. I almost spent hundreds of dollars on various Felicitys, but ultimately didn’t want to foist my longings on my daughter. Last year, I recounted this story to my dearest friend, and for my 40th birthday last week, she gifted me a Felicity in her original dress. I don’t think I’ve stopped crying since! And the best part is that both my daughter and my son are absolutely enchanted with Felicity and with the idea of a gift like this. There is so much inner child healing for me, watching my children play with the doll, and also being loved on by a fellow mama when I never really got that love myself as a child. And now this interview is here in my substack feed. 💕

What a great interview! I have a love/hate relationship with American Girl. I loved the books (that I’d borrow from the library) and once got the catalog. Let’s just say my heart dropped at the price tags. I was only 8 or 9 but I knew there was no way no how we could afford that. I never even asked my parents because it felt so shameful to even ask. I’ve carried that with me into adulthood and have never and never will go into an American Girl store. I can afford it now for my own kid but I absolutely refuse it. Take that, AG 🖕