The Fascinating (and Surprising) History of Women Drivers

Bonus detour into the history of market research

If you haven’t listened to this week’s episode of

, it’s one of my favs: on all things Dad Culture (and how Dad has no gender) with *excellent* dad (and dad scholar) Phil Maciak. And I can’t explain exactly why this thread on parasocial relationships with animals is as outstanding as it is, save: just trust me.One of the best parts of my PhD was going down archival wormholes that challenged everything I hadn’t even thought to question about my understanding about a moment in history, or how people during that time related to a particular idea, or how advertisers attempted to shift the understanding of who should buy something and why.

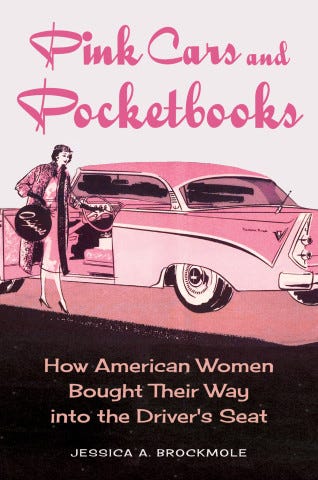

Hence my interest in Jessica A. Brockmole’s Pink Cars and Pocketbooks, which dives deep into the history of women and cars — and revises much of the stereotypical understanding of how car companies advertised to women, how it changed over the course of the 20th century, and how women advocated for better information about the cars they wanted to own and their access to “automobility.”

Read on to texture/challenge/expand your own understanding — and buy Pink Cars and Pocketbooks: How American Women Bought Their Way into the Driver’s Seat here.

I want to start with a passage from the introduction of your book and see if we can unpack some of the basics from there. You write:

“Women asked for clear, no-nonsense literature about how cars worked and what to do when something went wrong; the auto industry gave them cartoonish pamphlets that suggested applying lipstick and “looking helpless and feminine” when needing to change a tire. When women protested that they wanted roomy trunks and adjustable seats, the industry instead offered pink cars and matching pocketbooks. Frustrated at being misinterpreted, women wrote directly to automakers. Those letters went unanswered.”

What does the refusal to acknowledge women as consumers (and drivers!) of cars tell us about the way the car (and car culture) was and remains masculinized? Why was it ideologically necessary to belittle or outright women as drivers?

This exclusion of women from American car culture and the refusal to acknowledge women as equal automotive consumers was gradual and not, I argue, as overt an act of aggression as it might seem at first glance. Americans did not see the first woman on the road and react with outrage. Instead, I believe that, helped along by changing depictions of driving women in automotive advertisements and the media, women were taken less and less seriously as drivers. This marginalization happened over time as the auto industry used market research to confirm what they felt they already knew about women and technology and to package those assumptions in a way that made women’s automobility acceptable to American society.

When the automobile was first introduced to the American public at the turn of the twentieth century, it wasn’t yet coded as a “masculine” technology. The auto industry then was huge, with hundreds of small manufacturers all trying to figure out what Americans wanted in a car. They innovated countless designs, from steam-powered cars to electric cars that started with the push of a button, from long, open touring cars to tiny three-wheeled Motorettes.

In the first two decades of the century, automakers advertised widely in newspapers and magazines, to both men and to women, as they tried to find the ideal markets for their cars. Early automotive ads drew on imagery of the Gibson Girl and the New Woman, showing driving as being an activity for the healthy, outdoorsy, and free-spirited woman, and they offered positive messages about the enjoyment and independence women could find behind the wheel.

But that, of course, changed as time went on. By the late 1910s and early 1920s, automakers had a better idea of what sold and how to efficiently build those models. Automakers had to become more targeted in their advertising, selling their brand rather than selling their particular piece of automotive engineering. Curtis Publishing Company, one of the largest magazine publishers in the country, dove into researching automotive consumers and users in order to attract the auto industry’s lucrative advertising dollars. When they noticed very little auto advertising on the pages of their Ladies’ Home Journal, they began to specifically study women and their car purchases.

Despite all this research, however, the conversation between the auto industry and their female consumers remained relatively one-sided. These market researchers tended to interview the male automotive dealers that the women patronized rather than the female buyers themselves. When the researchers did occasionally question women, they cherry-picked the answers for their final reports that conformed to acceptable ideas about women and cars.

Despite interviewees talking about economy, reliability, mechanical prowess, and ease of driving, Curtis seized upon scant mentions of style and appearance and they highlighted these in their reports of the studies. These carefully curated results confirmed what market researchers, and the American population as a whole, already assumed about women and their preferences—that women might tremble at the thought of being responsible for such a powerful machine but might be persuaded to purchase one at the sight of a pretty body style.

No matter that women themselves said they appreciated mechanical innovations under the hood. Men were skeptical, and interviews with car dealers—who considered women in the showroom as flighty and clueless but nonetheless bossy and influential—validated that skepticism. This supposed confirmation, under the guise of research, reassured those Americans who had been anxious about women gaining ground in technology use. If all that women were after was an attractive car to be seen in, they would not really encroach in the masculine domain of technological knowledge.

In the early 1930s, General Motors introduced the idea of annual model changes, encouraging Americans to replace their old cars with new because of style and trend, rather than need. The advertising industry jumped on this, using fashion and glamour to market cars both on and off the pages of magazines. This type of marketing seemed to satisfy what automakers thought women were most interested in—namely, things like the lines of the car, the body style, and how nice it looked sitting in front of her house. Just as Curtis Publishing Company’s market research had seemingly reinforced accepted ideas about women and technology, this new fashion-focused marketing further reinforced those assumptions.

After a production and advertising pause during World War Two, there was a resurgence in market research as companies all fought for postwar consumer dollars. Women were again the focus of this renewed research. They were expected to return to the home and concentrate on the family, filling their houses and their lives with new consumer goods, including automobiles. Women’s magazines jumped into researching women and the cars they wanted to park in the driveway of their new suburban homes.

Unlike the earlier Curtis studies that largely interviewed male dealers, these postwar studies gave women more of a voice, surveying, polling, or asking them directly about how they shopped for and used cars. Women repeated that they prioritized safety, reliability, and economy in a car. They wanted features to keep backseats safe and clean for children. They wanted the ability to adjust the cars to fit their bodies and their needs. They wanted straightforward information about how to maintain and repair their cars. The postwar studies also included questions about appearance, paint color, and upholstery fabric.

As with the earlier studies, researchers highlighted these answers in their final reports—over the topics that their female respondents had stressed. The auto industry saw this as further confirmation that women only considered the car another attractive household appliance to adorn their domestic lives. Postwar automotive marketing to women stressed fashion and femininity, and positioned the car as a stylish tool to help women carry out family duties rather than as a machine to enjoy for its own sake. Despite asking for dependable, easy-to-operate cars and clear information about how to use, maintain, and repair those cars, women received increasingly gendered marketing that sold acceptable ideas about womanhood as much as it did cars.

This began to change in the 1960s and more quickly in the 1970s as women started bypassing the auto industry and creating their own channels of communication to share automotive knowledge. They shared automotive knowledge with other women through regular automotive columns in women’s magazines and newspapers, through handbooks and repair manuals, and through hands-on education. This take-back of automotive messaging was helped along by a growing interest in self-education and DIY that occurred alongside the second-wave feminism movement. It was also pushed along by the Women in Print Movement, a feminist drive that encouraged and facilitated knowledge-sharing between women.

Building on that idea — how much of the reluctance to understand women as drivers had to do with mobility, particularly self-mobility, and the public/private sphere? I love your use of the phrase “women’s automobility,” which absolutely drives the point home.

I started this project assuming that I’d see a lot of pushback against driving women in the earliest part of the century, as women were fighting for the vote and for a voice in the public and political spheres. It made historical sense to me. Instead, I found that, though stereotypes and jokes about “woman drivers” were present throughout the century, the images and texts about women at the wheel in the first few decades were overwhelmingly positive.

Stereotypes of women as passive automotive consumers, as poor drivers, as fussy and comfort-seeking car owners, and as uninterested users of technology have existed from the earliest days of the automobile. Some scholars have argued that these stereotypes were deliberately constructed in the early twentieth century by a society worried about women’s increased mobility and incursion into the masculine domain of technology.

Through jokes, cartoons, and cautionary tales about the “woman driver,” the auto industry and American society sought to discourage women from driving and to encourage men to maintain an exclusive hold on technical knowledge and automotive identity. Though men in the automotive industry and the media certainly presented women with discouraging, demeaning, and dismissive messages about feminine automobility—some that persist until today—I argue that these messages were less prevalent, less immediate, and less deliberate than the literature suggests. Looking at early twentieth century periodicals, I found almost fifteen hundred advertisements, articles, and images depicting and discussing women’s automobility. Only one percent of those promoted “woman driver” stereotypes. Sexism in automotive messaging did indeed exist from the earliest days of the automobile, but it existed alongside positive messages and hints of what automotive technology could offer modern women.

I think that many of the early ads do exactly this, showing women’s automotive competence and the possibilities that they might discover from behind the wheel. Women were shown driving through the countryside, exploring the open road, and standing alone next to cars sightseeing, picnicking, or just enjoying the outdoors. Their cars were portrayed as the means of mobility, freedom, and autonomy.

Along with the images and copy in these early automotive ads, readers encountered driving women in articles, stories, cartoons, photos, and poems. These women shopped for cars, drove them for work or for pleasure, maintained and repaired them, and used them to demonstrate self-sufficiency and even patriotism. This changed by the 1930s, when driving women were typically depicted behind the wheel of parked cars, with none of the action and agency of the earlier ads. The cars were used as props or background scenery, not as the means of exploration. Ads that had once sold intangibles like independence and mobility to women along with their new cars now instead sold status and success.

By the postwar era, the tone of ads had shifted again, often putting women outside of the car or even in the passenger seat. Women were rarely alone with their cars in postwar ads, unless they were engaged in domesticity, such as grocery shopping or picking children up from school. These ads made it clear that a woman’s car was an extension of her home and a space where she could continue to perform domestic tasks. By the ‘60s and ‘70s, when second wave feminism changed the language used in marketing and women began to have an influence in automotive messaging, ads shifted again and started showing cars not as means or spaces, but as identity. Women were sometimes shown in active positions behind the wheel but were more often shown posed possessively beside their cars. Women in this era were again pushing for space in the public sphere, but automotive ads did not reflect this mobility the way ads fifty years earlier had.

I found myself deeply fascinated by the section of the book on Market Research — first, just thinking about Market Research as a way of Taylorizing advertising, my head exploded — but also the way that Market Research conceived of women car consumers. Some readers already know about the history of Market Research, but I think many would love to hear more about how it weds psychology and advertising with the goal of targeting and containing “irrational” consumers.

Most historians agree that the origins of market research lie in the Progressive Era. The era’s reform movements and wide-spread embrace of efficiency, standardization, and evidence-based results primed a similar embrace of research in advertising, marketing, and sales. Market research developed alongside Frederick Winslow Taylor’s theory of scientific management, which called for a systemic approach to improving efficiency and productivity in the workplace. Market research utilized many aspects of Taylorism—using prediction to eliminate waste, systematizing work processes, drawing on knowledge rather than expertise—to manufacture a standardized and economical product more effectively. And the end product of market research? A streamlined and efficient ad targeted at its ideal consumer audience.

Applied psychology gained ground at the turn of the century, buoyed in part by the era’s general demand for scientification, and psychological principles crept into the business world. Early-twentieth-century psychology, with its emphasis on behaviorism, was particularly appealing to the advertising industry. Harlow Gale was the first psychologist to explore this link between the two fields of psychology and advertising, running experiments in the late 1890s to find out how people noticed, remembered, and were persuaded by ads. This kicked off a scientific advertising movement that transferred these ideas from academic spaces to business spaces in the next decade. Theories were not the only things that the business industry coopted from social science. Methods of social research—such as observing consumers in the field, sampling households, taking opinion polls, constructing questionnaires, and conducting interviews—and methods of analyzing statistical data were also brought into the business world.

The earliest market research efforts came primarily from magazine publishers, who utilized the platform of their publications and the ready subject pool of their subscription lists to administer surveys and gather information from a targeted market of consumers. Many of these initial studies looked at circulation between cities and sometimes between neighborhoods in an effort to boost magazine sales, but publishers did not only study their audience to understand where they lived. They also wanted to know who that audience was and what they bought. Through market research studies, women’s magazines attempted to define the average woman and, by asserting that these average women looked to the cultural space of the magazine for guidance, to promote her to the manufacturers and advertisers as the ideal consumer.

But their search for the average and ideal woman allowed magazine publishers to set boundaries of exclusion. When Curtis Publishing Company, which put out the popular Ladies’ Home Journal, began doing readership surveys and mapping circulation, they deliberately avoided neighborhoods inhabited by families that were either assumed to not be reading their magazines or by families that they did not want included in their idealized audience.

In the early twentieth century, these were neighborhoods where Black, immigrant, and poor families lived. Though a glance of subscription addresses would have revealed that readers indeed existed in these unsurveyed and “undesirable” neighborhoods, Curtis did not draw on subscription information in its market research. This selective research allowed them to assure potential advertisers that they would reach an exclusive audience in the Ladies’ Home Journal. To the manufacturer who wanted to reach a homogenized white, middle-class, native-born American population of women, Curtis Publishing Company promised exactly that. The fact that these demographics and circulation numbers were reported under the reassuring mantle of “research,” something that Progressive Era Americans were familiar with, lent a veneer of scientific legitimacy to these exclusions.

Later studies took their cues from these results in determining who counted as a “rational” and desirable consumer. Those who lived in wealthy or middle class neighborhoods were assumed to be intelligent, discriminating, and, of course, native-born white. Black Americans and immigrants were grouped together and—regardless of income, education, or situation—were classed as “illiterate” by market researchers and presumed to have little interest in the same American products or values as the “better classes.”

Regardless of having no data to back up such claims, these studies perpetuated what would become deep-rooted assumptions about class, race, and consumerism. These assumptions led to decreased advertising to geographical or demographic markets deemed to be inferior and to a broad dismissal of large swathes of American consumers. Market research studies gave marketers the tools to, with the seeming backing of science, contain and control “irrational” consumers. When magazines were the ones conducting the studies, this containment and control had ramifications beyond advertising; it shaped their very pages for decades to come.

And as a secondary question, for all the process and archive nerds: how did you access market research materials, and what is your approach to them as historical documents? Please take this one in whatever direction you’d like, Culture Study readers love this sort of detail.

I optimistically began this project in early 2020, with enthusiastic plans for research travel, archive visits, and writing schedules. I had searched for where big advertising firms had deposited their historical records, I’d located the libraries and collections of American automakers, and I’d tracked down the personal papers of women who’d worked at the intersection of both industries. I had scoured finding guides and identified promising boxes to dig into.

I had first come across Charles Coolidge Parlin and his work in market research for Curtis Publishing Company when working on an earlier project about consumerism and women’s magazines. By following mentions in the literature, citations, and references in finding guides, I uncovered decades’ worth of studies on automotive consumers, both unpublished and published, that Parlin and his Division of Commercial Research had done on behalf of Curtis between 1914 and 1932. I also found the advertising he did in trade journals and newspapers, selling both his research results and Curtis publications to those who worked in automotive manufacturing and advertising. The literature of advertising history, of automotive history, and of the history of consumer culture held little discussion about these market research studies and I was excited to fill that gap in the literature.

And then the unthinkable happened. Ready to dive into research and writing in the spring of 2020, I watched as archives, libraries, and campuses closed around me. I had to rethink, replot, and reapproach the project I had initially planned as I could no longer access all of the material I’d hoped to study. Beginning research the week after a pandemic shuts everything down is challenging, to say the least. Archivists, librarians, and research staff made this immeasurably easier as I pivoted to remote research, digitized collections, and interlibrary loan. No longer could I leisurely peruse boxes and folders in archives or books lining library shelves to see what I might discover; I had to thoroughly comb through online catalogs and finding guides to request loans and scans of what I felt would be the most helpful material. My careful preparation paid off. I had Parlin’s studies—even more than I initially knew about—and an abundance of other excellent material to work with.

Along with Parlin’s studies—both the unpublished data and published reports—and later market research studies, I looked at publications of the advertising industry, such as trade journals, research reports, and guides on marketing to women. I browsed through the archives of ad agencies that worked with the auto industry, reading through notes and correspondence regarding ad campaigns and also noting the newspaper and journal clippings that they saved when researching those campaigns. I also studied literature from the auto industry, such as trade journals, newsletters, expenditure reports, sales manuals, promotional material, and annual “facts and figures” books. I combed through articles, columns, photographs, illustrations, cartoons, and ads in national and regional newspapers. I read automotive handbooks, user guides and repair manuals, along with contemporary reviews and advertising for those books. And I looked through government publications for information on changing demographics throughout the century.

By examining these sources, I was able to compare market research with the messages in advertisements, promotions, and other marketing material to see if there was a disconnect between what the auto industry knew about women and cars and what they said. These sources also allowed me to track women’s voices, from the words filtered through interviews and surveys to the words written by them in articles, columns, letters, and books. Although this project, these questions, and these sources were not what I had originally planned, the history I ultimately discovered was fascinating and important.

I’m hoping we can take some of the historical rooting of your novel and analyze two contemporary, woman-targeted car ads, both for the Chrysler Pacifica:

The first conveys what I’ve come to think of as the classic minivan mom appeal — and, interestingly, not a dude in sight:

The second features Kathryn Haun as a very contemporary do-it-all mom (“It’s me, I’m the parents)

What feels very old to you about these ads — and what feels different? Would love to talk about whiteness, momness, homeness, presence or absence of kids and dad, let’s go everywhere.

Oh, these are delicious ads!

First of all, let me just say that in all of the market research studies I looked at across the whole century, in addition to other things, women almost universally asked for ways to make transporting kids easier, cleaner, and safer. I think that absolutely speaks to women’s never-changing role of primary caretaker—the one who would be driving a car full of children most often—but it probably also says something about the things that women notice and speak up for.

So all of these women interviewed and surveyed across the century would be extremely impressed and relieved at the options to keep kids entertained and secure, to easily clean up after said kids, and to tote all of the things of everyday life (I adored the detail in the second commercial that the cargo space would fit precisely 4,937 hot wheel cars). The women of the past would not only be thrilled at these the technological and design improvements, but I think they’d also welcome how much the commercials detailed these improvements and other automotive information. The longer Pacifica reveal especially highlighted the modernity, practicality, economy, comfort, and safety, while pointing out that these changes were “what the market wanted.” To me, they are clearly talking about the women’s market, as these are all things that women had been bringing up for ages, and I think those women would be happy to see those changes underscored.

But I think there is plenty in both commercials that might make the women of the past sigh and think, “We’re still doing this?” You’ve already rightly pointed out some of this—the lack of dad to help, the whiteness of the families—and to that I’d add the nice suburban house (complete with landscaping, manicured lawns, and outdoor furniture) and evidence of middle class consumerism (toys, bikes, sports equipment), both of which were omnipresent in women’s automotive ads by midcentury. Along with these familiar visual markers, the first ad also suggests mother as conqueror or intrepid adventurer. It shows children as being the wildness that mom, with the aid of her trusty minivan, coolly tames. The ad treads similar ground to ads like this one from 1966, where car travel with kids is equated to a third-class experience—complete with sticky lollipops, snacks, and a scatter of toys—that mom can elevate only with her choice of car.

Although there is largely an absence of kids in the second ad, it is still very much a “mom” ad. Along with other archetypes of women, Kathryn Haun plays diverse “moms”—sports mom, frazzled do-it-all mom, glam mom, influencer mom, mom of teens, career mom, hippie mom, and scouting mom—who each appreciate specific aspects of the Pacifica. Whether she is meant to be playing wholly different characters or representing the different hats that a woman and mother might play, it’s reminiscent of postwar ads that show women juggling the many roles they might play.

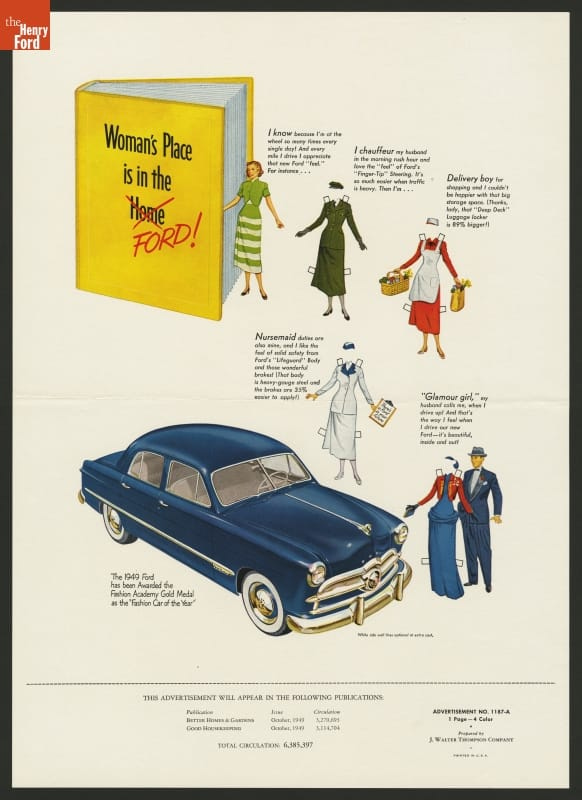

This similar Ford ad from 1947 is fairly straightforward, showing a variety of women from housewife and mother to working woman, but I also absolutely love this 1949 ad of a woman as a paper doll tucked into a book titled “Woman’s Place Is in the Home,” where the word “home” is crossed off and replaced with “Ford.”

She’s described as family chauffeur, shopper, caretaker, and arm candy. The ad copy does not give her an identity beyond her domestic role, a point I think is further emphasized by representing her as a static, two-dimensional, duplicable paper doll. There’s so much to say about this ad that I think also applies to the Kathryn Haun commercial. The paper woman’s domestic roles are portrayed as tabbed outfits in the same way that Kathryn’s are shown through outfit changes. Despite it being an ad for a vehicle, the woman—as a literal paper doll—has no mobility. Kathryn is not quite as inert as cardboard, but she doesn’t drive or otherwise put her car in motion.

Although the activities described and the correction from “home” to “Ford” all suggest mobility, the very nature of the activities tie her to that home. Similarly, the Pacifica Reveal commercial, in the later script, repeatedly makes the same point—“your home away from home,” “all the comforts of home even when you are miles from yours,” etc. Some things change, but some stay the same! ●

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, if you *value* this work and want to support it — consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.