If you go looking for hiking trails on the island where I live, you’ll find four. At least officially. They’re all maintained by the Lummi Island Heritage Trust, and are the result of decades of dedicated conservation work. Two used to be farms. One used to be a quarry filled with hazardous waste. The trails are lovely and marked and I use at least one of them daily.

But there are dozens of other trails on the island, too. Some of them feel like secret passages, like the one from the top of the hill that pops you out right at the back entrance to the library. Others were for maintenance of electricity poles now long defunct. Many are technically on private land, even if there’s no signs to indicate as much. But my favorite are through what’s called “open space” — a complicated designation used to describe private OR publicly owned land that keeps it un- or lightly developed. (I found this definition useful and you might too).

The first time I came to visit my best friend on the island, the first thing she did was take me to the open space, the opening to which is just a two minute walk from her house. About a quarter mile in, you enter a massive meadow with forest on three sides. At some point in the past, it was farmland of some sort (an old plow and a pieces of dilapidated corral suggest as much) but now it’s wild grass, which gets a haircut in late July (which helps prevent invasive blackberry spread and decrease fire danger, which is extreme in the summer).

The beauty there is quiet. If you yell — like, say, your dog’s name, because they’re off trying to roll in dead vole — the sound echoes back from the surrounding forest, And if you look closely, you can see the small trails leading into it.

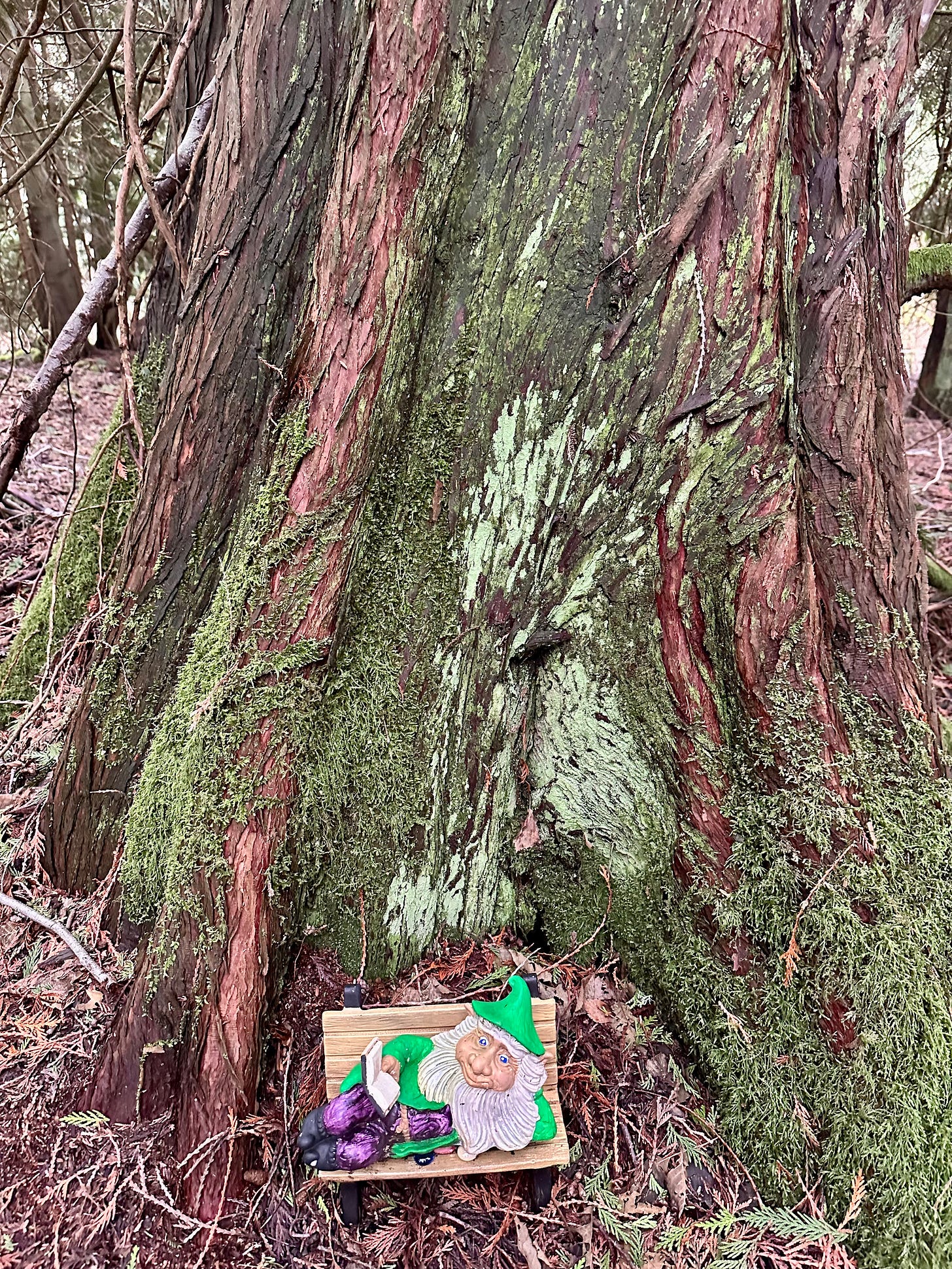

The forest is dense and damp and outrageously verdant. The trees are mostly cedar, with light green lichen climbing the slender lines of their bark. In the spring, there’s trillium and salmonberry and fiddleheads. In the winter, there’ muck. And in every season, there are trolls.

It’s not possible graphically convey just how many different types of troll (and troll-adjacent) adornment there are on this trail.

Like, I would guess 50 trolls? At least?

It’s whimsical, yes, but it’s also the work of someone who loves these trails very much. As evidence, there are several places on the trail with poor drainage that would be impassable for months out of the year if not for this sort of handiwork:

(It’s hard to tell here, but each of these bridges has some sort of traction so that the moss won’t make them just as slippery as the mud).

A good trail requires maintenance. Public trails are maintained through our tax dollars. The heritage trust trails are maintained through volunteer labor and donations. The same holds for these sloppy trails: they endure because people use and love them. Because they build and haul in bridges. Because they figured out which trees would benefit from a well-placed nose.

I am a huge advocate of public spaces and public land, both of which have added immeasurable value to my life over the years. I find myself continually persuaded by the arguments of Antonia Malchik (and many others) that private ownership of the commons is at the root of much if not most of what ails us. I’m mindful of the way my race and class markers grant me safer passage in these spaces, as it does in so many spaces — and how the fear of “trespassers” is rooted in these fantasies of ownership and control.

I also see the gorgeous tracts of land below the open space, also once used for farming and grazing, now on the market at mind-boggling prices, accessible only to those with extreme wealth.

I try to hold two thoughts in my head at once when it comes to this open space — which, as most people on the island know, is owned by a conservation-minded heir to the Hewlett-Packard family. These trails are free for anyone to travel. But they are not marked on any map. The only way to find them is by talking to people — or by taking the time to wander yourself.

That’s how I found the gnome trail, the library trail, and so many other unmarked trails: I got lost and curious. It took time and patience. And it was possible only because of the quiet, anonymous labor of others — people who put in the time not just because they loved the land, but because they wanted others to see its beauty as they did.

These not-so-secret trails feels like as good a metaphor as any for community. It’s complicated by tensions between public and private, between the wants of the individual and the needs of the collective and the maxims of capitalism. It needs continued work to feel safe. Sometimes it’s soggy and feels like a maze and other times there are rays of slanting light that take your breath away. There’s no precise map. The only way you can find it is by putting yourself out there or putting in the time.

I think a lot about the ways we explicitly and implicitly gatekeep various communities: by when and where we schedule meetings, whether children are welcome or accommodated, how people are thinking about accessibility and Covid precautions, how the group itself is advertised or promoted, whether there are membership dues or requisite volunteer hours, whether dissent is tolerated or frowned upon, the list goes on. Communities have to be constantly working on these things — and widening or eliminating the gates — if they want to grow and evolve.

I realized, while I was tromping around the open space contemplating this essay, that there’s a physical gate to the open space. I understand its necessity, the same way I understand the necessity of gates on various public lands. And here’s the thing: it’s always open. I’m grateful for that. But I spend a fair amount of time thinking about its capacity to close. What would be lost — and how little could be done about it.

Not every community needs to be public. But it’s good to remember what we risk when they’re not. ●

Make sure you check out this week’s episode of — featuring all the weirdest celebrity philanthropies.