If you value the work here, if you send it to your friends or revisit it, consider subscribing.

You’ll get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, the ability to comment, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the stuff that adds value to your life. Plus, there’s the threads: like Tuesday’s How Do You Find Good Stuff to Read on the Internet? and Friday’s deeply charming Things You Thought Were Universal That Were....Very Much Not (the sibling room swapping story is so good, and I keep reading the one about the watermelon knife in the parking lot and losing it)

The first time I watched a baby unsupervised I was in sixth grade. My mom was next door, but I was in charge. By the summer, I was taking care of two kids at a time, between the ages of 2 and 6, for hours at a time. In the teen years to come, I became a regular sitter for several families. I’d watch kids for several hours on a weekday night and for six to twelve hour swaths on the weekend. I’d give the kids baths and heat up chicken nuggets and watch Disney VHS movies. Most of my memories are of ambiently playing, grazing on their food, and waiting for time to pass.

It’s difficult to explain to parents who’ve never babysat how different the experience of watching a kid is when it’s 1) not your kid and 2) you’re getting paid. There’s no compulsion to multi-task, no feeling that “if I can just distract the kid for ten minutes then I can get this done.” You have one job, and that job is for the kids not to die or hit each other (or hit each other as little as possible).

In semi-rural Idaho in the ‘90s, my rate was $2 an hour, but I got $3 from the family where both parents were doctors. It went up slightly but not as much as it probably should have when I got my license and could drive myself to and from their houses. I used the money I made to buy Mossimo and Stussy shirts at the mall, to go to a matinee of Romeo + Juliet for the third time, and to buy temporary pumpkin orange hair dye for my next sleepover. I used it, in other words, to make monetary decisions that were mine and mine alone.

I also liked the babysitting part. It was easy to be silly with them, easy to shrug off their quirks and misbehaviors. If they didn’t go to sleep right away, if they refused part of dinner, if they threw a tantrum — none of those things made me feel like a failure. I was there to make sure they didn’t hurt, make sure they felt safe, and maybe also have some fun. The stakes were so incredibly low.

Babysitting continued my long education in the contours of boredom. Once the kids went to bed I’d listen to CDs with the volume on low or read their old magazines and try to very surreptitiously tear out the ads I collected (CK One, which makes me shudder, but also the Old Hollywood Gap Khakis ads). I knew some babysitters would call their boyfriends but I didn’t have a boyfriend so that was never a problem. Often I was so bored I’d just start vacuuming. Then I’d fall asleep watching 20/20 or the evening news and groggily accept a check and be on my way.

My time as a babysitter helped me get a job as a camp counselor which helped me eventually get a job as a nanny after I graduated from college. Once there, I marveled at how the professionalization of the work transformed it. When someone pays you $13 an hour to take care of two infants for 48 hours a week in the suburbs of Seattle in 2003, there are different expectations for how everyone, but especially the babysitter, should behave. I understand why — and also understand why and how early education is a real skill, one that should be valued monetarily and societally the same way we value medical care, construction work, you name it.

But babysitting — at least the way I and so many other people my age and older did it through their teen years — is not the same as being a preschool teacher or a nanny. It’s a different type of care altogether: dynamic, largely on-demand or on a vague sort of schedule, interstitial. You’re supervising kids and implicitly offering them a model of what it’s like to be older and a teen — but you’re not edifying them. No one asked for my resume. They’d usually just seen me with their kids or with someone else’s kids (at church, at neighborhood gatherings, at big parties attended by a bunch of my parents’ friends and their kids, where I’d reliably be one of the oldest) and thought: that’ll do.

Sometimes a parent would call asking if I could come over later that night. Usually, I could. I could because even though I was a serious student, had cheerleading practice four times a week and games on another two, volunteered for kid’s youth group and did a bunch of other church-related stuff and took piano lessons and spent a lot of time with friends….my schedule was never full.

Even senior year, there was always time to babysit, which is another way of saying there was always time for things that didn’t translate on my college application resume or otherwise bolster my “human capital.” That flexibility allowed me to help other parents who needed time, for whatever reason, away from their kids. It imbricated me in the community. It familiarized me with the tedium and intermittent joy of caregiving. It allowed me to try on different forms of responsibility and authority — and to be in control, for however limited a time, of someone else’s space, without surveillance.

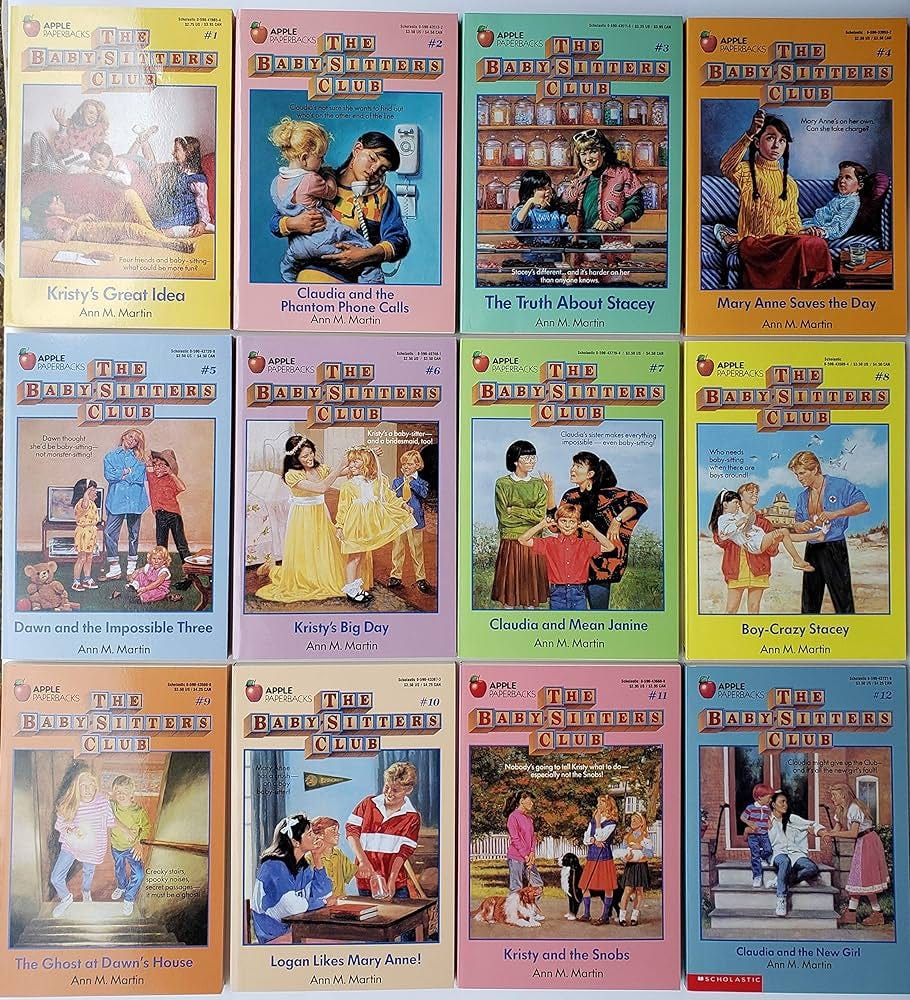

Maybe I was a babysitter because, like so many in my generation, I devoured The Babysitter’s Club — a never-ending series of books that organized the casual labor of babysitting into a formalized side hustle. I wanted that club! I craved such organization! I wanted style like Claudia and ease like Dawn and organization like Kristy!!! But even with plenty of fellow babysitting friends, we could never pull it off.

Or maybe I was a babysitter because I had so many great ones myself. There was Shelly, the babysitter to rule them all, with a shower of bright red curls. One year my mom asked her what CD she wanted for Christmas and she responded Guns N Roses Use Your Illusion II. God she ruled. She was goofy and bright and knew exactly how to keep my brother from annoying me. She gave our family a 5x7 of her senior picture and it sat in a place of absolute honor on our mantle.

There was Andy, our only male babysitter, who let us put way too much Magic Shell on our ice cream, and Emily, who was bored and quiet but lived just up the street and had great cascading bangs. Maybe it’s weird that I remember these names and practices and soft etches of their faces so many decades later, but you probably do too. I recall their presence just as vividly as my elementary school teachers. They weren’t adults, but they were in charge. It was fascinating and aspirational.

I’ve recently been thinking about these memories of babysitting: what it gave me, what it offered my parents and the parents of the kids I watched, what it modeled for those kids. I’ve been thinking about it in some capacity for years, as I watch my peers struggle to find a sitter who isn’t someone who previously nannied for them or another family in their neighborhood mom’s Facebook group. Teens don’t babysit anymore, they say, which is one of those things that feels true to a lot of people because it’s true in their own circle, even if not outside of it.

Still, it does feel like there are far fewer teens babysitting — and a number of theories as to why. Faith Hill attempted to untangle some of them in a recent piece for The Atlantic, pointing out that babysitting statistics are incredibly difficult to come by because the labor itself is so informal. Teen babysitters are paid under the table and work irregular hours. Is caring for a child full-time during the week “nannying,” and caring for them in the evening or on weekends “babysitting”? You can see the problem.

But are there actually fewer teens willing to babysit? Or are fewer parents willing to hire teens to watch their own young kids? For her piece, Hill interviewed childhood historian Paula Fass, who reminds readers that in the past, most kids — like me! — started babysitting at age 12, if not before. And yet “now more than two-thirds of American parents think kids should be 12 or older before they’re even left home alone. Several states have guidelines issuing a similar age limit; in Illinois, kids legally can’t be left unattended until age 14.” (This is absolutely wild — and absolutely a means of criminalizing parenting styles that aren’t the bourgeois standard known as “intensive parenting.”)

Hill also highlights how many (bourgeois) parents believe their young children’s non-schooling hours should be spent in “edifying” activities (tutoring, instruction, hobbies). If they do have a babysitter, it should be someone who can also teach them (I dunno, sounds like a governess??) even though they’ve already been in school for most of the day.

At the same time, parents of older kids (the potential babysitters) also believe that their kids should be doing something with their time that’s legible on a resume: volunteering, receiving extra tutoring, participating in (increasingly professionalized, increasingly weeknight and weekend-consuming) sports leagues. Or that they’re not mature enough to babysit (and to that I’ll say: the thing that makes someone mature enough to babysit is often having them figure out how to babysit).

There’s a teen babysitter supply problem, but there’s also a teen babysitter demand problem. Frankly, I think it’s a loss for everyone involved — and I think most people, including most parents, would agree with me. And yet: we can’t seem to figure out how to take something we find valuable, something so many of us think was a better way, something we have warm nostalgia for, and implement it in our daily lives.

Here’s where I acknowledge how the feminization and cost devaluation of teen babysitting can be connected to the ongoing feminization and devaluation of caregiving (and the wage gap). And I know that “casual” babysitting is a privilege in and of itself just like any number of “casual” teen jobs, as many teens are forced into babysitting to pay their family’s bills. I also think it’s a good idea to train babysitters in CPR and make sure they have some level of supervised experience, particularly with babies, before starting. I know, in other words, that teen babysitting as it was was was not perfect.

But I also think we are capable of nuance and adaptation and change. Want to do more foundational work in equalizing domestic labor in the home? Have your sons babysit. Want to have more models of fun, older, caregiving masculinity for your kids? Hire a dude babysitter! Want to teach your own kids that everything they do doesn’t have to translate into a line on their college resume? Encourage them to babysit. Want to feel more comfortable with teen babysitters? Start by having them come hang out while you’re in the other room. Want to underline the idea that there are a lot of people in anyone’s life who care for them, who they can talk to, who they can ask for help? Babysitters! Are! Great!

It’s easy to get on board with this theory, the same way it’s easy to join team Boredom is Good For Us and Analog Culture Gave Us Space to Feel Things. We have a deep nostalgia for these aspects of childhood, much of it related to the idea that we (Young Gen-Xers and Millennials) were the last to experience The Other Way. Some parts of that Other Way sucked (especially the rigid straight patriarchal cis-gendered whiteness of most of it) but other parts were essential to our sense of self. We are who we are because we had to wait to check our email or didn’t have it at all. We are who we are because not every song was available to us at age 16. We are who we are because we spent hours babysitting, or working shit after-school jobs, or staring at the ceiling.

But we are also so very bad at working to recreate the cherished parts of that experience for our children — because we are very bad at letting go of our own bad habits and broken thinking. Kathryn Jezer-Morton wrote about this tendency when it comes to phones last week in her newsletter for New York Magazine, describing a small study she did as part of her master’s degree in digital anthropology:

I interviewed a group of women about when and why they spent long amounts of time on their phones and measured their phone-use windows. What I found was that most of these women timed their epic scroll-and-text sessions to coincide with their kids’ screen time. It was a tiny study, but I noticed something: They were giving their kids screen time largely in order to accommodate their own.

She admits that she stepped away from this research because it was 1) fraught and led to shitty conversations and 2) made her feel sanctimonious and bad. But that doesn’t mean she’s stopped thinking about it, the same way I feel like I find myself continually returning to ideas about teen babysitting.

With her characteristic wit: “It’s been a private obsession that is tedious to bring up, so I never do. No one wants to talk about it. We’re all on our phones too much, we all know it, and we make our peace with it individually. The idea that parents need yet another thing to feel bad about is perverse. What do I want to do, lose friends? Hate myself forever?”

Jezer-Morton keeps thinking about it because people keep worrying about the effects of screens on kids, and writing books, like the one published last month by Jonathan Haidt, that suggest that the root of all that ails kids is the phones, stupid. You’ve likely seen this book or excerpts from it or reactions to it floating around, because it offers an answer many parents want to hear the same way they want to touch a bruise: yes, the phone is the problem.

And yes, the phone is the problem. I know this because the phone is also my problem, and it’s likely a lot of your problems, too. But that’s the part of our nostalgia for a phone-less past that we’re largely unwilling to address — because the fix is too fucking much. As she puts it:

The impossible condition of parenting is part of what has gotten us here. Parents work too much, and there is no affordable care infrastructure anywhere. It is inevitable for many parents to be working while trying to care for young children. But we do a lot more on our phones than work. It’s where we socialize and stay in touch, and the inflated amount of time we spend texting alone is a monopolizing factor. Is it possible that we have reached peak texting? Would it be possible for us to text less? I am nauseated at the thought of texting more — I truly hope we’ve hit our limit, but who am I kidding? We are at least as addicted to our phones as our kids are; we need them in order to relax. And since we don’t feel safe letting our kids wander around the neighborhood freely while we scroll in peace, we keep them inside with us, scrolling.

What I appreciate in this piece — and in all of Jezer-Morton’s work — is her ability to both acknowledge what led us here, and just how shitty it is, while also refusing to utterly excuse all behaviors we’ve adopted as coping mechanisms. Phone life is how we’ve figured out how to live, and how our kids are figuring out how to live. But it is not how we have to figure out how to live.

Nostalgia is potent. Plenty of people have wielded it in deeply regressive ways, reenacting ways of life that privileged them — but only at the cost of others’ subjugation. But that’s not how nostalgia has to work.

When you think about the things you loved about your childhood, what feels like an utter loss, what’s missing from kids’ lives, it’s useful to stop and ask yourself: when was the last time I made space for any of those things in mine? ●

For today’s discussion, I’d love to hear about your own teen babysitting experiences or thoughts — but I’d also love it we could all try to do what Jezer-Morton does and 1) acknowledge the structural stuff that makes things hard while also 2) calling out our own bullshit. Difficult, I know! But worth attempting.

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I also read the Babysitter’s Club books in the 80s/90s and started a babysitter’s club. I advertised at church and we made sure everyone knew that if one of us couldn’t work, we’d call someone who could. We worked all the time, sometimes 2 at a time with rich families with disabled kids. It was hugely empowering and fun and certainly contributed to me later becoming a teacher and l, I think, a good one pretty early on. Notably, it also paid for my wardrobe at a time when my parents were barely scraping by. The work was important.

I tried to get my kids to babysit when they were young teens but:

1) it’s just not done. I don’t understand it but folks are just not in the market somehow. Maybe it’s the small town thing, and people’s sisters and moms are doing the work? But the moms I talk to are exhausted and isolated; I think they’re just not going out. I think it’s the intensive parenting thing that Anne calls out.

2) What could my kids buy with what parents can pay? If the parents are going to the movies, they’re spending $50. Then they need to pay my kid enough to go to the movies (when I babysat in the 90s, one job with 2 kids paid for a night at the movies with snacks and maybe an ice cream after, or 1/2 a Gap shirt). So say you paid my kid $10 an hour …now their date is almost $100 and Netflix is looking good.

3) Young teens can’t go to the movies or out for ice cream without “their grown ups” now. I tried to let my kids go to the park or the coffee shop on their own but there was only one other mom who would allow these jaunts. Our town is 2 miles across! We know the coffee shop owners, and everyone else!

4) Kids don’t need $ to socialize; they only need phones. And in the early teen years, it’s less scary and weird than like, working, or than the kind of socializing you’d spend money on

5) I am a stepmom, and the first time I left my 8 and 10 year old home to go to the store for 15 minutes, their mom (who is not usually insane) threatened to sue for sole custody. Moms in the neighborhood were like, “Well, I always take my 14 year old to the grocery store (2 miles away!) with me…”. We have incredibly responsible and resourceful kids. It shocking

Last reflection: I did start babysitting regularly when I was 10 because I looked older and I think that was a Bad 90s Decision™️ but 12 is just right.

Babysitting as a teenager is definitely a fond and formative memory for me, for a lot of reasons outlined in this piece. (Ditto being babysat as a younger kid.) In my own life, it feels like it was a really important step up from being a child into being an adult. It was meaningful, immersive, hands-on practice for a lot of adult responsibilities.

I don't have kids myself, but I wonder how much of that practice-adulting has been replaced (in theory) by the grind of modern-day childhood and youth, the never-ending activities that are all intended to optimize a kid's chances of success in our modern capitalist hellscape. That stepping-stone to adulthood isn't hands-on or communal, but more likely to be isolated and competitive. You don't get to practice-adult by babystting (or camp-counselling, or lifeguarding, or what-have-you), but by packing your waking hours with college-application-friendly activities; and this burns out both kids and parents so much that the "breaks" in the form of screen time feel absolutely necessary just to maintain sanity and snatch a bit of psychological relaxation.