The other day, I did something I try very hard not to do. I commented on a NextDoor post.

On the island of ~950 full-time residents where I live, NextDoor has become the digital meeting point of choice. Unlike most NextDoor groups, it’s managed to stay informational and relatively non-confrontational, partly through a pretty firm ban on political discussion. The biggest arguments I’ve seen are over whether it’s okay to feed the deer (absolutely not) and the future of the new ferry (mind-bogglingly complex). Most of the time people post pictures of the sunset, alerts if a pod of orcas is going past the island, or talk about whether the ferry or power or internet is out and for how long.

Last week, one of the main community organizations on the island announced that The Tome — a newsletter it had sent out, in some form, since 1966 — would soon cease to be published in print form.

I’ve screenshotted the first page of the first Tome I ever read above, but it’s a poor approximation of what it’s like to read the Tome in print form. It’s usually somewhere between five and six pages, all double-sided and jammed full. It’s printed on that big, long paper (aka legal paper) and arrives three-fold. If you’ve ever read a church bulletin, that’s the approximate feel. (It was also always in a different bold pastel until the price of colored paper went through the roof during the pandemic).

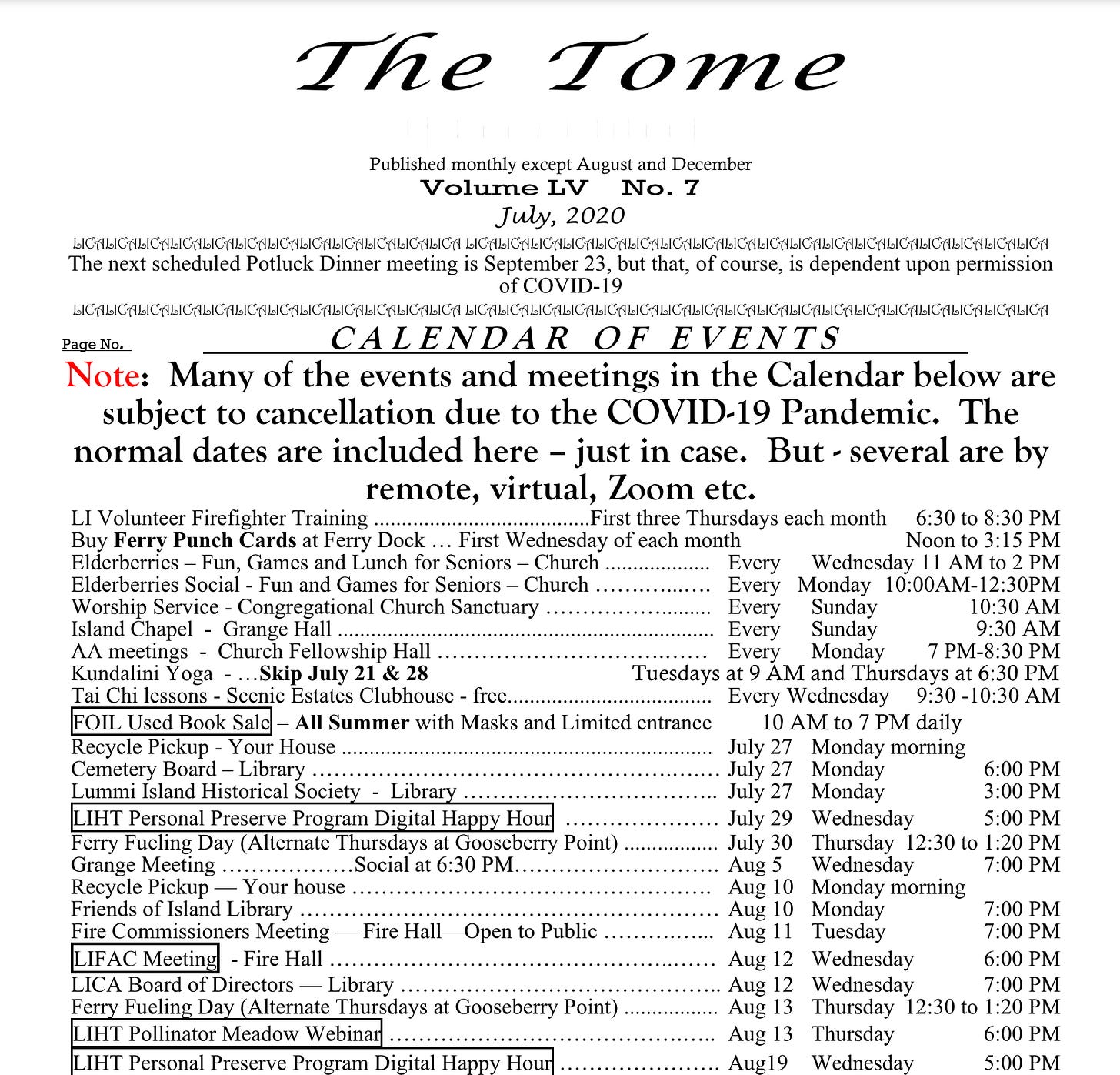

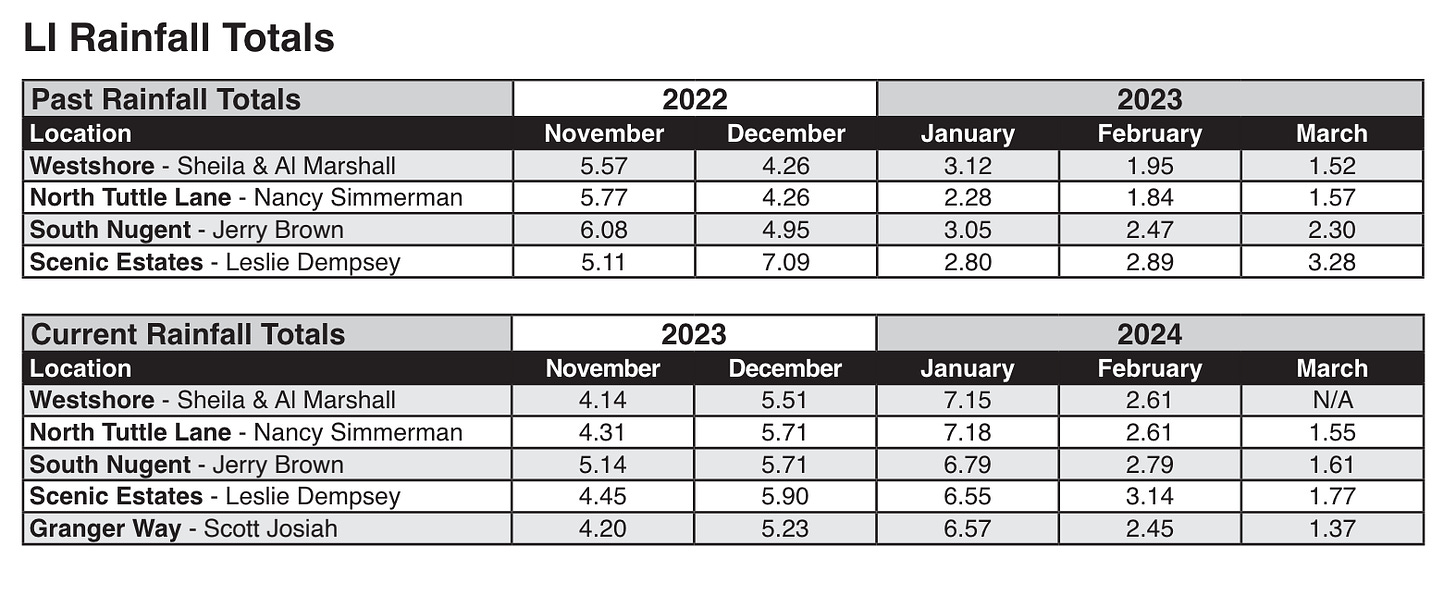

On the first page, there’s a listing of all community events, from the “Elderberries” Lunch and planned ferry outages to cemetery board meetings and recycling pickup. Most people (myself included) take that first page and hang it on their fridge. There are little updates from various organizations, little ads for on-island services and businesses, and my personal fav, the monthly and historical rain accumulation from four different places on the island. There are histories and lengthy obituaries, corny jokes and artist profiles. A delight, truly.

I began reading The Tome the way most people on the island began reading The Tome: because it was in my mailbox. The organization that publishes it (Lummi Island Community Association, or LICA) uses bulk-rate mail to get it into every mailbox and PO Box on the island. Some people throw it directly into the recycling bin, sure, but others read it the way I do: as the one piece of practical and quirky interest amidst the sea of catalogs and political mailings and bills that make up the contemporary postal experience.

When you donate to LICA, you also get access to a sort of supplementary online newsletter, but I never read those, the same way I never read any other community or organization newsletter that shows up in my email, no matter how ardently I support their cause. I’m always looking for ways to spend less time in my inbox. Reading The Tome allowed me to do that and remember when it was a ferry refueling week.

Recently, the board of LICA took a look at their budget and saw the potential to save $4000 in annual savings and four trees worth of paper by ceasing bulk mail production and moving to an online-only format. Their proposed idea: have a handful of print copies available at the local library and general store for people who still like a printed copy, and then direct the saved funds to other community grants.

I absolutely see the logic here. In addition to the cost and trees, producing a printed product requires volunteer labor — every month, a small group comes together to fold and tape the copies, which then have to go to the post office to be bulk mailed. That’s time and dedication. I want to be clear that I value the work that LICA does in our community tremendously, have been a regular contributor since moving here, and appreciate the willingness to talk about this decision in a public way. I also know some people dislike having another piece of paper in their inbox the same way I dislike another LLBean catalog. Yet I still found myself reacting so strongly to the idea of a digital-only Tome that before I could talk myself out of it, there I was, posting a long paragraph of a comment on NextDoor when the board president asked for feedback.

I spend so much of my day wading through digital correspondence. A very small percentage of it is delightful or engaging, but most of it is tedious at best and absolute trash at worst. I know that someone who writes a newsletter for a living gets more emails than the average person, but I also know that most people, regardless of vocation or age, are also fatigued by the daily work of reading information online. In many cases, that fatigue turns us into our worst selves: we ignore; we ghost; we leave messages unread until the guilt shames us; we put up filters that allow the sea of news and announcements wash over us without affecting us.

The Tome provided the inverse of that experience. There were no comment sections, no way to performatively repost it online. There was just low-stakes island stuff that made parts of this community legible. Figuring out how things work in a new place can feel like trying to pick a lock blindfolded. The Tome felt like a key.

In the U.S., congress mandates access to mail service, which is part of the reason that even though our car ferry has been out for the last three and a half weeks, we’re still getting daily mail. They haul it, in wagons, on and off of the foot ferry. A marvel!! The mail is essential community infrastructure in a way that email can and will never be. And one of the great components of that infrastructure is the ability to reach every resident, no matter their age or income or vocation.

The Tome came to me not because I’d taken any initiative or known someone before I got to the island. I started reading it because it was there, and it was there simply because I was, too. Put differently: I didn’t have to opt in. The invite to be part of the community was already in my mailbox.

If I came to the island now, chances are high I’d eventually find myself on The Tome email list. Maybe someone would buttonhole me at the farmer’s market or I’d see a prompt on NextDoor and sign up. But that’s because I’m a busybody community-minded person who engages in this sort of thing. Even then, it’d enter the sea at the bottom of my inbox. Maybe, maybe I’d read if I was procrastinating on something I really didn’t want to do, but you have to open a PDF and that’s hard to read on mobile and blah blah blah, even just typing out this reasoning makes me feel like a lazy piece of shit. But I’m also trying to be an honest piece of shit. Logically, email would be the best way to reach someone like me: a person who spends most of their working hours on the internet. But in this case, that’s precisely why it doesn’t work.

We’re in a baffling and fascinating moment in communication and what we now call “content delivery.” You can see it in the push to go back to phone calls and the rise of voice memos — and in the spread of informal-ish newsletters like this one, the ongoing decline of social media, and the popularity of “storytime” TikTok. It’s there, too, in physical books’ refusal to die, and the vinyl boom, and the quiet success of high-end niche print-only quarterlies.

There’s the age-old desire for “authenticity,” of course, and the refreshed allure of a physical, own-able object. But I also think people are trying, truly trying, to be more intentional with how they interact with others and with the media around them — and to figure out which avenues work best for which types of content. How do I actually stay connected with my closest friends? How do I concentrate on a work call? How do I encourage myself to engage in someone’s work, and how do I best get others to engage with me? What’s baffling and fascinating is that the answers are rarely predictable. What’s “easiest,” most streamlined, or cheapest is not always best or appropriate or right.

If a consultant looked at our current situation with The Tome, they’d probably recommend what the board of directors has suggested. Cut costs; reduce labor hours; reach younger people. But what if what’s made The Tome essential reading was its physical form? What if the goodwill and donations directed towards LICA were, in large part, inspired by the physical presence of The Tome in people’s homes? What if the best way to reach young people is actually to do the opposite of what you might assume would be the most direct way to reach them? What if the most sustainable practice isn’t reducing paper use, but increasing community connection and resilience?

A printed and mailed newsletter isn’t the right solution for every community, just like a Marco Polo group isn’t right for every friend group and a phone call isn’t right for every work relationship. But now that we, as a civilization, have figured out all these ways to access everyone and everything all the time, the hardest work is no longer in the delivery. It’s in the discernment.

That’s the work I’m advocating for here. I’m not against change. I’m not against digital forms. What I’m for is a collection of paper staring back at me from the fridge door, reminding me of the heritage of community on this island. I’m for the ideal, sometimes practiced better than others, that you belong here not because of your last name or the price of your home or even where it is on the island, but simply because you are here. And that — that is a service whose value is impossible to price. ●

For discussion today, I’d love to hear about how you’re practicing this type of discernment in your life — figuring out how best to communicate with friends or family or coworkers, sorting through your various inboxes, engaging with newsletters or music or podcasts, or crafting your own organization’s or community’s communication with others.

Alternately, I’d love to hear about *your* version of The Tome: it doesn’t have to be an old school print newsletter, it can just be something that really does its job exactly the way it is.

I write letters. I have for years and both regularly to the same people and spontaneously to others and less regularly. For $0.68, to me, a miracle happens: You drop an envelope with a written letter in a box and a few days later it shows up to the recipient. Time travel happens at that point as what they are reading is, most often, a few days old. Then if there's a reply and a conversation starts this way, it's all the better.

Writing a letter forces me to sit down and be present with that person: with my words, reflections and thoughts and how I want to share those with the individual I am writing to. It's not instant, which is why it is so good. Reading a letter is similar: I need to find time and space and a place to sit down and open the envelope and read it.

Simply wonderful.

One specific example is my recent move to use my phone spontaneously to call friends and family. While I fully embrace the scheduled call when there are degrees of difficulty like significant time zone chasms, etc., that instinct to set everything up ahead of time had permeated my phone habits broadly (a byproduct of our digital lives to be sure). I decided this works against the very joy of a phone call with one of my loves: connecting across time and space. The act of placing a call randomly shouldn't be a radical act, but it felt that way at first. Sometimes I reach a person at a good time, many times it's a voicemail. But it never feels like wasted effort: I get a happy jolt of connectivity regardless. This might be in part due to the fact I embrace my reputation for the epic voicemail message!