The Jews of Summer

"I was trying, in retrospect, to get to the heart of why I was the way I was, and why the Jews around me were the way they were."

Do you value the work that makes this happen twice a week, every week…that makes you think and introduces you to new thinkers and books and just generally thinking more about the culture that surrounds you?

Consider becoming a subscribing member. Your support makes this work possible and sustainable.

Plus, you’d get access to this week’s really great threads — yesterday’s on The Most Perfect Places You’ve Stayed and last Friday’s on “what are you struggling to leave behind,” which gave me so many ideas to push me out of the mid-March blahs.

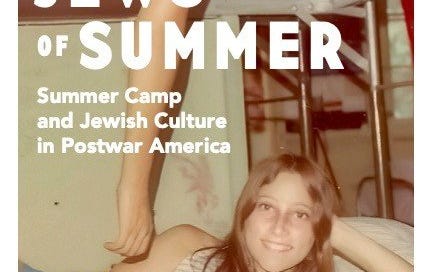

I saw the cover for The Jews of Summer, and I knew, immediately, I needed to read it. The crappy metal bunk beds with the springs visible below; the at-home-ness in that corner of space that was yours and yours alone; the grainy photo itself, almost certainly developed after returning home, maybe sent (in a letter!) to your camp friend as a promise that you’d see each other again, next summer, at camp. I love reading about camps, because regardless of the type of camp — science or French or religious, luxurious or bare bones — there is something so layered and fascinating about them, a curious mix of concerted adult-conceived programming and kid-led counter-programming that unfurls and builds over days and weeks and even months. A camp can ostensibly serve one educational purpose and, in practice, serve quite another.

But I also wanted to read a whole lot more about Jewish camp, particularly through the lens of a historian of Jewish culture: how and why it developed, the different types of camps and the differences in programming and ideology, how adults conceived of the purpose of camp compared with kids’ experience (and memories) of it. The Jews of Summer delivers all that and more — it’s so readable, it’s richly researched, and it asks provocative questions about the purpose of camp in general and Jewish camps in particular, all of which we touch on below. I love this book and I loved this interview — I think you’ll see that pretty clearly as well.

Sandra Fox is the Goldstein-Goren Visiting Assistant Professor of Hebrew & Judaic Studies at New York University, and director of the Archive of the American Jewish Left in the Digital Age. You can buy The Jews of Summer here, and find Sandra’s website here.

Because I went to a whole lot of nerdy summer and religious summer camp myself — some expensive, some very very cheap — I often forget that most people have had very few or no experiences with it. I know that Jewish summer camps differed/differ somewhat in length and focus, but can you describe a “typical” Jewish summer camp experience for readers who haven’t attended themselves?

One of the main reasons American Jews created their own camping sector is because they were not welcome in most camps owned and operated by gentiles in the early 20th century. But besides this shared reason for existing, the Jewish camping sector was already incredibly diverse by the mid-1920s, and only became more varied and hard to talk about in one breath in the decades after World War II.

There were camps that were primarily recreational and secular, where Jewishness meant that the camp was a place where Jewish kids could feel socially comfortable and safe among their coreligionists, but very little Jewish educational or religious content was included. There were camps that were like that but for Orthodox children, that mixed sports and other forms or play with praying three times a day and providing strictly kosher food, but also provided little education.

Camps owned and supported by various kinds of charitable organizations — settlement houses or the YMHA [Young Men’s Hebrew Association], for instance — existed to take immigrants or the children of immigrants out of cities and into the fresh air, often with assimilationist aims. Privately owned camps for more middle class or emergently upper class Jews, which relied purely on tuition, served families that had been in America longer. Some Jewish camps segregated children by gender, but most did not; Jews embraced coeducational camping faster than gentiles, largely because the progressive, socialist, and radical camp leaders that led the move towards mixed gender camping were, in many cases, Jews.

The camps my book focuses on are camps with intensively ideological, educational, nationalistic missions — the Jeweyist of the Jewish camps, not “Jew-ish” camps, which are their own totally legitimate thing with a whole other story that someone should write a book about.

All of the sorts of camps I mentioned so far would have shared certain classic American camping activities on their schedules: arts and crafts, singing, dancing, Color War games, hiking and other nature-focused activities, campwide festivals, sports. But camps sponsored by Zionist or Hebraist movements, Yiddish schools and institutions, and the Reform and Conservative movements of Judaism infused Jewish ideas, languages, politics, and cultures into every aspect of daily life. The crafts they made, the games they played, the songs they sang — absolutely everything was filtered through the lenses of Jewish culture and Judaism. These camps even ran an hour of educational programming every single day in which they could make their missions even more explicit.

In the early 20th century, most Jewish camps of all types were in the northeast of the United States, where Jews lived in highest numbers. They spread in the post-WWII years around the midwest, and eventually to the south, west, and southwest, as Jewish communities sprung up in sunnier cities like Miami and Los Angeles. How a child ended up in a given camp was sometimes a matter of luck or circumstance, but it often aligned with something the parent wanted for them or for his or herself. Parents often heard about a camp from friends who sent their kids to one, were happy with it, and decided to send their kid to the same place; sometimes parents chose a camp for the Jewish upper crust to assert their place in that segment of the community. In the case of ideological camps, parents often chose camps that aligned with their own politics or that were sponsored by organizations they were a part of… but not always. They might hear about camps from Jewish newspaper articles or advertisements, friends, or, in the case of Reform or Conservative camps, from their local rabbi.

One similarity between all Jewish camps is the typical length of their sessions. Historically, Jewish camps have run for sessions between 4 to 8 weeks in length. This is a pattern that emerged in the northeastern United States, and many protestant and simply “secular” camps in the northeast operated for a similarly long session time. But because Jewish camps began in the Northeast and spread outward, they tended to keep this longer session pattern no matter where they went. The length is also different from most Christian summer camps or “church camps” in America, which both historically and contemporarily have tended to run anywhere from a weekend to two weeks.

Part of why I suspect so many Jews feel extremely passionate about camp, then, is the fact that they tend to go to camp for a long time each summer, and often summer after summer, for years. Not all Jews attended the same camp year after year, but if they continued to go to a camp at all, they usually stayed at the same one. To unscientifically use myself as a case in point (a thing I never do in the book, because “scholarly integrity”!): I went to a Zionist summer camp for 4 weeks in 1998, and then for 8 weeks every year through being a head staff member in 2011. That means I spent over two years of my life at my camp from age 9 until 22. The youth movement that sponsored my camp also had a gap year program in Israel, so at age 18, I went to Israel for 10 months with all of my friends from camp, where we continued to be educated according to the same ideologies our camps had fed us. Three years with my camp people; three years immersed in my camp’s intensely Zionist ideology. A huge chunk of my young life that I had to write a deeply researched book to process.

You position the expansion of Jewish summer camp amidst what’s often referred to as a “golden age” in American Judaism, coinciding with the expansion of the Jewish middle-class, moves to the suburbs (and larger synagogues and community centers) and general affluence….but also a profound ambivalence about that affluence and a fear of a weakening or dissolution of Jewish culture in the wake of the Holocaust. Can you talk through that ambivalence, how it contributed to “child-centered” Judaism, and how camps figured into the equation?

Jewish historians have had an awkward relationship with the study of economic history, because talking about Jews and economics can feed anti-semitism. But the fact that Jews experienced unprecedented success and affluence in America is a part of American Jewish history that cannot be overlooked, and is really relevant to why sleepaway camp holds an outsized place in Jewish culture in this country.

Your readers might know the gist of this, but I do want to set the historical stage anyway, because this background is so crucial. From the 1820s through the 1920s, 2.5 million Jews left Europe for the United States. In Europe, they enjoyed few rights and faced the threat of anti-semitic violence; in America, they experienced great economic opportunity and, for the most part, embraced “becoming American.” In the 1920s, however, a time of growing nativist sentiment, Jews faced serious limits on their ability to socially, educationally, and professionally integrate. Anti-semitism was very real in this country, and the status of Jews in America’s racial paradigm was not yet clear to vast swaths of the American public.

By the end of WWII, the tide of American public opinion towards Jews was becoming more favorable, due to the realizations of the Holocaust. Not all social barriers came down, and people still held anti-semitic beliefs at the level of a whisper, but anti-semitism no longer had a place in polite society. This sea change enabled American Jews to do better socioeconomically than ever before in history. The steady economic progress they had made earlier in the century mixed with America’s thriving postwar economy to catapult them into the middle class. Their whiteness secured, they benefited from the same housing loans and educational scholarships as other white Americans, and they joined other white urbanites in the move to the suburbs.

All of these historical circumstances meant profound change for how America’s Jews did Jewishness. The synagogue center, with its sisterhoods, men’s clubs, and other social offerings, provided new Jewish suburbanites official and tangible ways to affiliate with Judaism, replacing the informal, neighborhood-based affiliations of urban communities earlier in the century. Coinciding with what many have described as a “golden age” for American Judaism — a time marked by social mobility, affluence, and suburbanization, and the development of what Herbert Gans coined as “child-centered Judaism” — the period saw the dramatic growth of synagogue Hebrew schools, nursery schools, youth groups, and, indeed, summer camps.

All of this sounds pretty cozy. But what my colleagues Lila Corwin Berman and Rachel Kranson have so brilliantly illustrated is that many Jewish communal leaders actually felt very ambivalent about the impacts growing affluence and social comfort were having on Jewish life and culture — that the golden age was not so golden after all. Affluence damaging a culture is perhaps the ultimate first world problem, but it is important to remember that all of these anxieties came into shape in the shadow of the Holocaust. The realizations of the Holocaust’s scope added an extreme level of urgency to their distress about the state of Jewishness. Without European Jewry to look to and with Israel’s future uncertain, postwar American Jewish leaders were suddenly responsible for carrying Judaism and Jewish culture forward into the future more or less alone. The sense of loss was a very heavy weight.

What I found in my research on summer camps matched Kranson and Corwin Berman’s findings. Rather than celebrating their new place in American society, educators, rabbis, lay leaders, journalists, and others projected these concerns onto youth and parents in particular, citing a growing need to develop Jewish identity in children. Camps, they believed, were ideal places to develop those identities, due to their 24/7, totalizing nature. While Jews went to camp earlier in the century, the post-WWII moment is when a communal obsession with the power of camp to save Judaism takes hold.

I love how the book, as a project, declines to focus on the question of whether camp “works” (in the case of Jewish summer camp, whether or not it can “transform children, repair the perceived inauthenticity of American Jewish culture, stem assimilation, curb intermarriage, and build up support for Israel”) and focuses instead on the very notion of a “good” “essential” or “authentic” that can or should be the goal of Jewish (or any other religious) cultural institutions. I’d love to hear you elaborate a little more on that idea, how you arrived there, and the larger hope for all readers of the book.

At every scholarly or public-facing lecture I’ve given over the past eight years, someone has asked me some version of the question “Does camp work?” I get why people ask me this. Jews who remain anxious about the state of their people in the 21st century want to believe that camps really are the solution they pitch themselves to be. They want scholars to tell them their hope and investment is valid. While I get the impulse, I’ve long been skeptical about the premise of this question. Who decides what constitutes “success”? Historically, those who do the counting demonstrate a camp’s success by tracking things like whether its alumni support Israel in all of the normative ways “good American Jews” are supposed to (giving money, visiting regularly, supporting organizations like AIPAC that lobby on Israel’s behalf); whether they married fellow Jews and made “Jewish babies” (the Jewish community is pretty obsessed with Jewish babies, an understandable outcome of Holocaust trauma); or whether they went on to join synagogues or be otherwise active in some form of official Jewish community.

In my twenties, I started to receive requests to fill out surveys by scholars and educators who wanted to trace what the impacts of my Jewish educational experiences were. In answering those surveys, I saw how easily Jews who have deep Jewish identities — but don’t align politically or ideologically with the mainstream Jews in charge — could fall through the cracks of their methods. How about alumni who see their criticisms of Israel as a direct result of growing up in a Zionist environment, as a sign that I actually do care quite a bit about the country’s future?

As I see many friends who are deeply committed to their Jewishness marry non-Jews, I am evermore skeptical of the idea that high interfaith marriage rates = the end of Judaism. I often wonder if the kinds of people I spend time with (largely left-wing, unaffiliated with mainstream Jewish institutions but practicing Judaism their own ways, diaspora-minded millennials) are considered American Jewish education’s greatest successes or its deepest failures. This is why I became more interested in figuring out how these ideas of what a good, successful Jew looks like came to be in the first place. My hope is that by pointing to how various visions of ideal Jewishness came about, I might spur some Jewish youth organizations today to expand them for the sake of a far more interesting, open, and diverse Jewish future. I’ve already been invited in by a few organizations, which indicates that there’s an interest in evaluating some long-standing norms in American Jewish education.

I was fascinated by the section of the book on how Tisha B’Av — which played, in your words, a “minor” role in American Jewish cultural life — became, along with Holocaust Remembrance Days and Ghetto Days, such an essential fixture of the Jewish summer camp experience. Some of it, as you point out, had to do with the fact that it was the only Jewish holy day that overlapped with camp itself, but also functioned as “a potent reminder of just how fragile personal and communal status and security can be.”

Can you talk more about how different types of camps approached these days, and how that’s changed with time? [I am so interested in how, for instance, Ghetto Night became a sort of “get serious” form of camper management]

ֿI would be curious what percentage of your Jewish readership has ever even heard of Tisha B’Av, the Jewish holy day marking the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and a whole host of other Jewish historical tragedies. It is more or less ignored in most non-Orthodox communities because it falls during July or August, when synagogues are empty and Hebrew schools are on pause. But as the only holy day to fall in the summertime, Tisha B’Av offered a moment in the summer schedule to pass the traumas of Jewish history to the next generation, these young people who only knew American comfort and relative social acceptance.

I don’t mean to sound blithe, but Tisha B’Av’s message at camp could often be boiled down to: “Hey, you know how you feel pretty good in America? Well, Jews thought they were safe in X, Y, and Z place and time in history. Guess what happened next.”

Camp leaders concentrated more on making an emotional impact on campers than an educational one, harnessing the day’s gravity by way of moving, creative ceremonies. As one of the camp directors wrote in an archival source I found on the topic, when it came to Tisha B’Av, he saw with his own eyes that “a little suffering goes a long way.” It went a long way in making kids feel less comfortable in America, and, as you allude to, it also went a long way in getting them to be more committed to their camp’s ideology, and to behave a little bit better at camp on the days and the days following, and to listen and learn with more intentionality.

Punctuating the highs of camp life with a scheduled emotional low, Tisha B’Av and its secular alternatives, like Camp Hemshekh’s “Ghetto Day,” memorial days and commemorations appeared rather similar on the surface, often beginning with tragedy and sadness and ending with stories of resistance, heroism, and survival to encourage pride. At the same time, their resemblances lay in the fact that Tisha B’Av’s religious rituals and laws provided camps a kind of how-to manual that they could build off and adapt to their young audience.

At Zionist, Conservative, and Reform camps, Tisha B’Av observance always began at sunset with campers attending a solemn, candle-lit ceremony, where participants sang mournful songs, listened to a chanting of the text of Lamentations, and performed dramatic accounts of historical tragedies on stage. Depending on their age, many campers fasted or ate simpler meals until sunset the next day, which they spent attending low-energy activities like educational discussions and film screenings related to the day. Even as most eschewed the religious rites and rules of the holy day, Yiddish camps’ rituals were also extremely similar, and the meaning-making rituals involved in Yiddish camps’ memorial days offer a fascinating microcosm for rethinking the notion of Jewish secularism itself. Ardent secularists, it turns out, desired rituals, too, and sourced within their rejection of the religiosity of Tisha B’Av a whole new set of customs that produced strikingly similar effects.

I wish I could tell you how that’s changed in more recent decades. The bulk of my research ends in the 1970s. All I know is that my Tisha B’Av experiences from 1998-2011 were pretty similar to the ones I pieced together in the archives, and that Tisha B’Av traditions seem to be quite embedded and stable.

What I can confirm is different is how the day has been experienced by campers at different times in history. For the campers of Camp Hemshekh, many of whom were the children of Holocaust survivors, their camp’s memorial day was powerful on a deeper, more personal level, a day when many of them found out about what their parents had gone through in detail for the first time. For a Zionist camp I found that marked Tisha B’Av in 1944, I can only imagine how viscerally memorializing the Holocaust as it was still underway felt, and how much it legitimated the camp’s Zionist mission to campers and staff alike.

Your question is making me wonder how camps are dealing with the rising anti-semitism in America today, and how events like the Pittsburgh Tree of Life shooting might become a part of Tisha B’Av ceremonies, if they aren’t already. I’ll have to ask some of the current camp directors I know. But there’s no doubt in my mind that campers in summer 2023 are going to relate to Tisha B’Av differently than I did in 2002, when anti-semitism in America rarely entered the news cycle.

UHHHHHH CAMP ROMANCE! I was so thrilled it got its own chapter. You point out that a certain amount of permissiveness was necessary to get campers to buy-in to the entire enterprise of camp as a place they want to be, but I want to hear more about how camp implicitly and explicitly modeled and/or prompted romance, relationships, and marriage.

I just recently published an excerpt of this chapter in Slate, and one comment that kept coming up was from several annoyed readers (I know, I know, never read the comments) was that they didn’t think anything about Jewish camping is unique when it comes to sexuality and romance — that teenagers are teenagers, pure and simple. I agree that teenage hormones are universal, and camps of all sorts have reputations for laxity. What is unique about Jewish camps, however, is the particular reasons camp leaders have had to keep things loose. Jewish leaders saw specific benefits in allowing camps’ romantic cultures to flourish.

Part of what my research shows is that giving campers the ability to pursue the opposite sex helped foster the association of camp life with freedom essential to receiving buy-in from campers. Nothing specifically Jewish there, except that Jewish camps had ideologies to get campers to buy into in a way that recreational, secular camps do not. But perhaps more critically, romance at camp was also harnessed to shape campers’ values surrounding marrying fellow Jews, and to drive home certain ideas of authentic Jewishness: Zionist leaders fused camper culture with notions of Zionism’s “promised erotic revolution,” their laxness surrounding sexuality adding to camps’ simulation of Israeliness. Dating and sexuality became core to Jewish camping, then, not only because campers arrived curious and desiring, but because adult leaders figured out how to harness the behavior of their teens and preteens to their own evolving missions and interests.

Camps modeled these values in a variety of ways. Jewish campers spent most of their days and nights in coeducational activities, providing ample opportunity for romance or desire to blossom, but staff also cultivated specific moments in the weekly and monthly schedules, such as camper socials, for relationships to begin and to thrive. Between the last activity and lights out, Jewish camp leaders generally permitted older campers to walk themselves back to the bunks, creating a window of opportunity for couples to find privacy somewhere around camp in an unlit and unoccupied room or outdoor area.

Former campers recalled that Friday nights emerged as the most popular night of the week for coupling off and seeking out some privacy, as later wake-up times on Saturday meant later bedtimes and dressing up for a formal Sabbath dinner intensified the sense of romantic possibility. The time between the end of the evening activity and curfew could last anywhere from ten to twenty minutes, enough time for campers to have some kind of sexual interaction. Anything resembling full privacy, however, proved difficult to come by, and the environment’s inherent limits assured leaders that time spent in the dark together would remain relatively innocent (ie. clothes more or less on).

Messaging surrounding Jewish marriage was also pervasive in the more implicit or “hidden curriculum” of camp culture. A male camp director and his wife, for instance, provided a Jewish family structure for the entire camp to observe and internalize. Marriages need not be official, however, to make an impact on campers. Camps across the ideological spectrum held fake Jewish wedding ceremonies, with campers or counselors in full costume under the chupah (a Jewish wedding canopy). Such activities hearkened back to Catskill traditions of fake wedding ceremonies as fodder for creating celebratory parties set to klezmer music.

But at camp, simulated weddings also functioned as forms of experiential education that taught marriage rituals and asked campers to consider “the importance of each part of the ceremony” as they watched and participated. Campers role played as brides or grooms at camp carnivals or festivals, too, where “marriage booths” allowed them to “marry” friends or summer flings. Alongside camps’ sexual and romantic allowances, these make-believe weddings played a role in promoting Jewish marriages. Receiving photocopied “marriage certificates” and rings made of strings or fuzzy pipe-cleaners, this common activity implied that your crush, camp boyfriend, or camp girlfriend could be more than just that with time, an official recognition of camps’ roles in bringing couples together.

Finally, I want to know how you, personally, found yourself academically interested in the history of Jewish summer camp? And for the process nerds in the audience, can you tell us a lot more about the work that you did in various archives (and Facebook camp alumni groups) to piece together this history?

Although I had a bunch of academic reasons why Jewish camps made a good topic of research, landing on it as the center of my dissertation and then first book project was definitely in part about me processing my own experiences at camp and where they left me in young adulthood. When I entered college at The New School and started taking classes that touched on Israel-Palestine, I felt really blindsided by my Zionist education. I started to read books by Israeli “post-Zionist” scholars and books by Palestinian academics on the Nakba. I realized that Israel was not what my camp and youth movement told me, a fact that caused me a lot of emotional turmoil.

When I started my PhD program at age 23, then, I was on a journey when it came to my Jewish identity, trying to figure out how to replace all that Zionism with something else. I learned Yiddish and started a podcast in the language, embracing diaspora Jewishness. I started attending prayer services again because I found there were alternatives to the dull Conservative synagogues of my youth and the Orthodox ones I had tried that did not align with my feminism and leftism: independent groups of young Jews who did things on their own terms, without a rabbi and often in people’s houses or in other ad-hoc places. My twenties, in other words, were a time for Jewish experimentation, and all the while I was writing this dissertation that was about how places like my camp came to be in the first place. I was trying, in retrospect, to get to the heart of why I was the way I was, and why the Jews around me were the way they were.

Over the years of working on the project, though, my years at camp got further away from me. By the time I was truly writing it, I rarely thought about my own experiences, partly because I wrote about such a diverse array of camps, not only Zionist ones, and about decades when I wasn’t even alive yet. I worked hard to keep some degree of distance and to write about things as objectively as possible. But of course, my experiences at camp led me to believe that there was something important about telling this story, and my own Jewish journey guided me towards looking at some of the lesser explored areas of Jewish camping, like Yiddish-oriented camps. I also think my generational remove mixed with my own Jewish political, religious, and cultural journey allowed me to write a history of Jewish camping that is both broader, covering a vast array of Jewish camp types, and less rosy than many of the other works on the topic.

I explored multiple archives, but spent the most time at the Center for Jewish History in New York, which houses both the American Jewish Historical Society and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. The archival research process took me about a full year of focus and then I went back and forth to them throughout writing. I also conducted oral history with over 30 campers from across the decades, a spectrum of camps, and tried to get a balance of gender and sexuality. Facebook groups of camp alumni were really helpful for getting answers from multiple former campers at once, like if I found something in the archive that didn’t make sense to me, I could ask them for clarity. It also was how I found oral history subjects, and most critically, a ton of amazing pictures, 21 of which are in the book! ●

Many thanks to Sandra Fox for such an in-depth and expansive interview. If this interview piqued your interest (or if you know it would pique someone else’s!) you can buy The Jews of Summer here.

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

My guest host for this week’s WORK APPROPRIATE is psychologist Hammad N’Cho, who specializes in counseling people traumatized on the job in any number of ways. We address listener quandaries on how to move forward while also looking backwards and addressing the source of the trauma itself. His advice is at once empathetic and clarifying, and I hope you’ll take the time to listen. Click the magic link to listen on your app of choice.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

Wow wow wow.

I went to a Jewish summer camp for probably about 7 consecutive years of my childhood, and I was absolutely obsessed with camp. It felt like a totally separate universe I entered each summer, for a little over a month, which felt like a lifetime.

It's an experience I reflect on a lot as an adult, as there were so many oddities surrounding the experience, and it was SO impactful on my development.

It's also something I think about for a similar reason as one that the author stated - I've done a lot of reflecting on the urgent zionist propaganda that was infused in so many of my experiences of Judaism as a child, and the extreme political conservatism tied up in a nationalist identity more broadly. Detangling the cultural, religious, and political teachings and experiences of Judaism is complex for a lot of people as they grow up and become more critical of what their families and institutions taught them. Some of those teachings are ideas I now find totally appalling and in complete opposition to my worldview, but they were positioned as being fundamental to Jewish identity. The economic piece was huge in my experience too - I grew up in a Jewish community that was very proud of wealth accumulation, and wore class status on their sleeve both literally and figuratively. I felt a lot of shame around "not being really rich". (so wild)

For me, all this ultimately resulted in my feeling totally and completely alienated from my Jewish identity, even though it defined my schooling as a child (I went to a day school!) and my summers (I went to a Jewish summer camp!). I grew up with SO MUCH Jewish tradition, and it is not AT ALL a part of my life in any way anymore. I feel okay about that, but I do wonder if things would have turned out differently if some of those formative features were different...if there was less unquestioning zionism, less affluence and materialism, less social and political conservatism around gender and sexuality, etc.

Re: the part about romance/sexuality/marriage simulation at camp - We lived in "villages" based on age, separated by gender. Then, eventually, you ended up in a co-ed village in your final year, which I believe was the summer before 9th grade? We had two counselors who were dating in this co-ed village - I will never forget them, even as so many important details of my childhood drain from my brain as I age. Their names were Bryan and Haley (I think.). We did a "mock wedding" for them as a real event. It is SO bizarre to me looking back on it, and I am so struck to learn that "wedding simulations" were a common event at Jewish camps! Ahh! This is something I've always been like, "...well that was weird" remembering back on, but it was actually a typical Jewish camp thing?!

God, I have so many thoughts about Jewish summer camp. Hello to any other Tamarack campers who read the AHP newsletter.

EDIT with additional thought: It occurs to me how interesting it is that for older generations, Jewish camp was perhaps supposed to make me more connected to my Jewish identity and more likely to carry it on, and yet it ultimately did the opposite (though in the immediate sense as a child, it was effective). My experiences at Jewish camp and Jewish day school actually made me feel more alienated from the Jewish community in the long-run. I know it's something I could explore now as an adult in different contexts and environments, but just thinking about "the goal" of camp...it backfired for me completely.

This post is absolutely speaking my language. I went to Ramah Poconos for four years, followed by two at USY summer programs, and every bit of this scholarship rings accurate to my experiences. I liked the Slate excerpt too when I saw it. I definitely noticed the tacit encouragement of teenage heterosexual romance and felt very weird about it as a nerdy queer kid. The politics were also markedly notable, definitely including those camp Tisha b'Av observances! I'll be getting the book - the only debate about it in my household is whether it's an ebook just for me or a print book to share with my spouse.