This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

In the first edition of the series, I outlined the ways in which some Master’s programs have begun to employ for-profit practices with prestige lighting. In the second edition, I attempted to loosely group the wide array of Master’s programs in various fields. For this final installment, we’re focusing on “predatory inclusion,” the racialized components of student loan debt, and better conversations with undergrads.

Anytime I talk about student debt — and graduate debt in particular — I get a wave of responses claiming that these students should have known better, thought more about their job prospects, sought better counsel. A lot of that data just doesn’t exist. These fields are often so niche, it’s hard to find — or know — anyone who’s taken the route you dream of. There are no comps, no reliable “average salary” results on Google. There’s just your old pal Meritocracy Myth, telling you that if you work hard enough, you’ll make it.

People have long tried to make it as professional athletes, in movies, on the stage, and as writers despite the odds. For decades, there have been students who’ve believed that education, no matter the form, would pull their family out of poverty or provide a solid path to American citizenship. And there have also always been individuals and bad actors who’ve tried to profit off of these hopes and dreams. The difference is that now that hope is being spun into student debt by programs effectively backed by the federal government.

And even if that debt does end up offering some manner of wage premium, the debt itself is not neutral.

Sociologists Louise Seamster and Raphaël Charron-Chénier argue that student loans function as a tool of “predatory inclusion, i.e. ., the “process whereby members of a marginalized group are provided with access to a good, service, or opportunity from which they have historically been excluded but under conditions that jeopardize the benefits of access.”

In other words: student loans make undergraduate and graduate degrees accessible, but the loans themselves “reproduce inequality and insecurity for some while allowing already dominant social actors to derive significant profits.” You might get your foot in the door as a librarian, in other words, but you will not have the security, the ability to save, or the ability to accumulate wealth in the same manner as your peers who did not have to take out significant loans to get there.

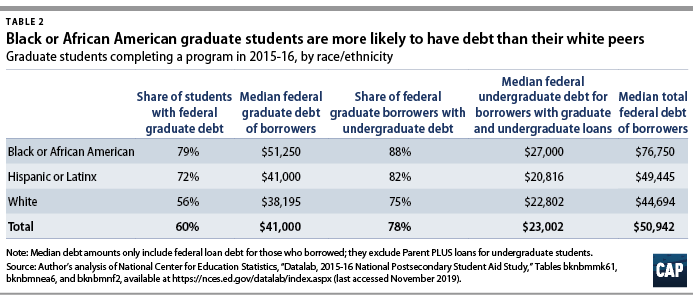

“Educational debt accumulation,” Seamster and Charron-Chénie argue, “is a racialized process.” 79% of Black graduate students and 72% of Hispanic grad students take on student debt — compared to 56% of white grad students. Black and Hispanic borrowers borrow more, and are more likely to have undergraduate debt. The median total federal debt for Black graduate students in 2015-2016 was $76,750 — compared to $49,445 for Hispanic graduate students and $44,694 for white graduate students.

As sociologist Frederick Wherry put it to me earlier this year, “It’s one thing when you finish school and you can see your debt going down,” Wherry told me. “It’s quite another when you finish and the interest and your ability to pay means that it just keeps going up. Those are the realities that no one tells you about as a senior in college. And they definitely don’t say, ‘Hey, for our Black students here, about five years after you graduate, you’re going to owe $50,000, even though you finished with $26,000, and that’s going to be double what your white counterparts owe.”

People who’ve navigated these systems and emerged with significant debt sometimes defend the system by saying the program’s expected debt is “manageable.” But those conversations frequently leave out for whom, exactly, that debt is “manageable.” For people without kids? For people with undergrad debt? For people who need to support members of their extended family, either in the United States or abroad? For people with partners, or whose partners are employed full-time?

Loans decrease any degree’s “wealth building” function — and, in so doing, decrease their ability to anchor the recipient and subsequent generations to the middle class. These degrees don’t close the racial wealth gap. In some cases, they work to actively sustain it.

There are so many reasons why many fields (especially, say, library science) struggle to attract and retain people of color. But any industry reflecting on its enduring whiteness should begin by scrutinizing its credentialism standards — and the amount of debt (or private funding sources) required to achieve them.

So what do we do about all of this? Some argue that students are adults, and adults should be allowed to make decisions about their future — and then deal with the ramifications of those decisions. But prospective students can be adults and also be vulnerable to grad school appeals, and we can be a lot better about unpacking those vulnerabilities before they’re exploited.

That work starts with better, more accessible data.

The Department of Education’s “College Scorecard” is currently oriented towards undergrads, and shoddy design has made it incredibly difficult to even access graduate data. It had taken me hours to figure out how to access the information, but I wasn’t sure if I was just bad at navigating the site. Turns out, nope, the site is just bad.

Earlier this week, I challenged subscribers to the newsletter to figure out a straightforward statistic for an NYU Master’s program — or to find out statistics from any other graduate program. None of them had been able to surface graduate data for even a single program on their own. The labeling of the data is poor, it only covers public loan balances, and many grad programs are missing median loan data, median salary data, or both. Is it because the programs are too small? Unclear, because the Department of Education doesn’t communicate what the “basement” is to make data difficult to anonymize. I’ve seen programs with enrollments over 20 and no graduate loan data, and programs under 10 with graduate loan data. The inconsistency is maddening and, more importantly, unilluminating.

We need better data, we need better visualizations of that data, and the data itself needs to have better SEO, so that when prospective students Google “University of Chicago MAPH average debt” it takes you directly to the page that says $65,471. This goal isn’t to turn every program into some crass Return on Investment (ROI) checklist. It’s to give people a baseline of debt information before enrolling. If the federal government refuses to act on loan forgiveness, the very least it can do is work to make this information accessible and legible.

The work continues with reckonings about “value.”

Should a program cease to exist because its projected salary is less than its debt? Not necessary. In many fields, the debt-to-salary ratio is too blunt of measuring tool (I appreciated Brendan Cantwell’s run-down of why, for example, several MBA programs at HBCUs would fail the test — and why that’s more indicative of racist hiring practices than a cash-cow of a program).

Instead of telling students in public service fields with considerable wage-benefits that they should simply shoulder their debt and cross their fingers for PSLF, we should significantly decrease the cost of public programs, broaden financial aid, and treat them more like the advanced certifications they are.

But some of these master’s programs should not exist, at least not in their current form. Truly wild debt-to-income ratios like those at Columbia’s filmmaking MFA should prompt an in-depth review. In some cases, a program should be axed. At elite schools with massive endowments, if a program with a massive debt-to-income is still deemed fundamental to the school’s mission, it should either be fully-funded or need blind. (Yale, for example, just made its Acting MFA tuition-free — with the help of a $30 million gift from David Geffen. More gifts endowing tuition-free programs, more!)

But we ultimately need to be honest about the role of some of these programs, even if the institutions themselves refuse to do so. If they’re PhD prep, call them by their name. If they’re Finishing School for well-resourced students who don’t know what else to do, call them by their name. You might think those programs are good or bad or worthwhile, but they’re distinct from other Master’s programs, and should be publicly discussed that way.

And then there’s the topic of funding. Many academics now tell students on the potential PhD path to never take an offer without “full funding.” But “full funding” can mean a lot of different things, many of them cloaking necessary debt. I ostensibly had “full funding” at the University of Texas and still paid thousands every semester in hidden fees — plus, because of the meager grad student pay and lack of general funding, took out loans to cover cost of living, paying rent during the summer when no funding was available, and paying for my own conference travel and research costs. (The typical graduate travel ‘grant’ when I was attending: $200-$300 a year).

If you have to take out more than a few thousand a year in loans to make it through the year in a “fully funded” PhD, it’s not fully funded. Full stop. We should be advising students how to ask the right questions about what funding will look like, how long it lasts, and, most importantly, the average debt load of graduates. That’s not nosy. That’s due diligence. Then prospective students need to ask themselves: Is that number a number you’d be comfortable paying off even if you can’t find work in your field? Even if you have to pay ten to twenty percent of your monthly income for the next twenty years, regardless of where you live or the cost of your rent?

You can value the education you’d receive as a part of your degree and also find it not worth that ongoing cost. But you have the appropriate tools in hand to even begin to make that decision.

The work hinges on those still in the system.

Two years ago, when I wrote about academics and MLMs, I tried to describe how so many students find themselves in grad school. A teacher, probably one you admire or that you’ve figured out how to please, tells you that you’re good enough, smart enough, potential-filled enough, to go to grad school. Maybe it started when you wrote a paper you were particularly proud of, and your professor told you, off-handedly, “maybe you should think about grad school.” When my undergrad professor told me as much, it was like someone had unfogged the windshield of my life: oh, yes, there’s the road in front of me.

Part of the reason some academics give this advice to their high-achieving students is they don’t have a lot of other advice to give. They took that route; it’s what they know and, most importantly, a subject on which they can can actually give detailed counsel. When undergrad students came to my office asking for help finding internships, for example, I was useless. But the route to grad school? That I knew.

I developed a speech that I used to talk about not taking on debt to attend school, and what an MFA in filmmaking could and couldn’t provide, and the realities of the job market. But a lot (but certainly not all) of these students were white, and came from upper middle-class backgrounds. They were attending a competitive liberal arts college. Most had never really been acquainted with a time when meritocracy hadn’t worked for them. Why should they believe me, someone who seemed to have won the game, sitting in the professors’ chair across from them? If I could do it, they could do it.

When I left academia, that may or may not have changed some of their thinking. But I still wish I’d had better ways of discussing the reality that were much more effective than just “the job market is a nightmare” or “I have over $100,000 in student debt.” For most students, my debt number wasn’t real — just as it wasn’t real to me when, in their same place, I began applying to grad schools, and ended up enrolling up enrolling as an out-of-state MA student at the University of Oregon without first-year funding because it was “the best” of all the schools I got into, and took on more than $35,000 in debt that first year while working two part-time jobs.

Future conversations, particularly for students in the humanities, have to start early — not when they’re in their junior or senior year and terrified of their lack of job prospects and asking for letters of recommendation. As I wrote back in 2019, what I wanted most as an undergrad was to keep thinking about film and literature the same way that my favorite classes allowed. What I didn’t understand was that there were so many ways to do so that weren’t grad school. So how can we shift the conversation from closing doors to ones already open?

If you’re advising students, if you’re getting asked to write letters of recommendations, or even if you’re just a grad student who spends a lot of time with undergrads, it’s imperative to not just be transparent about the way you got where you were — because a lot of students will take that as proof that they, too, can suceed — but also educate yourself about the potential trajectories of majors in your department.

That doesn’t mean directing a student to the career counselor’s office, where they’ll meet with (and likely dismiss the advice of) someone who doesn’t really know them or their aptitude. Instead, maybe that means asking the career center to meet with your department to talk about the reality of the field and its offerings. It means touching base with former students about where they are and how they got there — and connecting them with current students. It also means having difficult conversations about how getting into good colleges and getting straight A’s in your major and being good at homework does not necessarily mean that you will be the exception to the rule when it comes to the employment dynamics of a given field.

In the course of reporting this story, I heard from faculty members and grad students who’ve established policies against letter writing for certain programs, and continue to refine the conversations they have with undergrads. Some have fought diligently against new or concerning graduate programs in their own schools. They’ve collected data, formed committees, and jeopardized their relationship with administration. This resistance is often limited to the tenured, and while some have succeeded, others — like the faculty committee at the University of Chicago, which suggested decreasing enrollment numbers in both the MAPH and MAPSS — were effectively ignored.

I think it’s essential for individual academics to keep thinking about these issues, but I’m also incredibly wary of resting the burden of resistance to an exploitative system on the individual. This work is hard! It is exhausting and often lonely! It is too much to ask of academics who are already overworked, underpaid, and often operating in institutions and states that are already hostile to them.

Plus, sometimes career advising is under-resourced or filled with people with very little understanding of your field! And sometimes the biggest problem is coming from inside the house, from the faculty member who doesn’t see a problem with these programs, who has no understanding of student debt or what PSLF even is, let alone that it is broken, who receive criticisms of the current system as criticisms of themselves or their work — and who are veritable founts of bad advice. How do you counter that guy? And how do you muster the energy to do it when you’re teaching a 4-4 load?

I don’t have answers, but I do have more questions to consider that don’t simply involve the individual. What posture should current graduate students (and their unions) adopt towards these programs? How can adjuncts and grad students and tenure track professors act on the idea, as the University of Chicago grad union put it, that “our exploitation is shared, but so is our solidarity”? How do we tangle professional associations — like, say, the American Library Association — from the schools and programs that facilitate credential bloat in the field? How do we imagine new models of higher ed while the old, broken, business-driven ones continue to entrench themselves?

Everyone I’ve spoken with for this piece, whether still in academia or spit out by it, agree that these Master’s Trap programs are symptoms of larger rot at the core of a capitalist model of higher ed. That model isn’t going away soon, but without agitation for change, the cycle will just continue, and another wave of students convince themselves that with enough hard work, enough prestige, or enough letters behind their name, and a strong enough stomach for debt, they’ll beat a system stacked against them.

A very select few do beat that system, usually through some combination of skill, connections, and luck. But the tragedy of the Master’s Trap is its ability to animate the most hopeful, confident part of yourself, then leave it to devour itself in disillusionment and debt, desperate for any route out. A lot of adult life dulls our hopes and dreams for our best selves. But few things do it quite as surgically as grad school. And if for no reason other than that, we should continue to agitate for reform.

I often wonder what would need to happen to imitate the intellectual stimulation of a great humanities MA outside of an institutional setting that still leads to the unlocking of doors within a particular industry. Is it a really well organized book club? Is it a job search group of BA holders in a certain area that get together to discuss big ideas, best practices in job seeking, and future plans? I do understand that we've over-credentialed so many fields in our country, so any non-institutional intellectual outlet would not have the weight to lead to improved outcomes to under-employed, smart BA holders, but there has to be a way to chip away at the institutional stranglehold of employment in certain industries. Or, do these folks just need to suck it up and become a cog in the corporate wheel?

I have been following this series with great interest. Amazingly, my college undergrad humanities professors gave me *very* transparent and useful advice when I asked them about grad school options. The history professor whom I really admired told me "I have a moral obligation to tell you that there are no academia jobs and it's not a good investment for you to pursue a history Ph.D. What you should do instead is gain some applied policy and research skills and find ways to work in the history aspects you've liked into a more stable career path. Also you should work for a few years first and then go from there."

I am grateful to this day for his honesty, and that's pretty much exactly what I ended up doing. I worked for several years and am now in a fully funded and very applied policy PhD program - it *still* feels risky but the program's job placement & salary track record outside of academia is extremely good and now I have prior work experience to draw from. I think it helped that he gave me options for things I *could* do rather than only telling me "no, don't do this."