The Millennial Vernacular of Getting Swole

Muscle Milk, The Rock, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Men's Health, and Brad Pitt's Abs

This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen.

Last week, I wrote about the millennial vernacular of fatphobia. Today, Emily Contois whose research focuses on the intersection of food media and masculinity, addresses how body ideals for men played out during the same time period. Next week, we’ll have a piece from historian Angela Tate about negotiating the images and ideals of the ‘90s and 2000s as a young black woman.

Paid subscribers, your supports means I’m able to pay these writers an above-industry rate for their analysis. (If you’d like to support future guest writers, here’s how to subscribe).

Content Warning: This post discusses body image and diet culture.

In our youth, the ideal for so many young Gen-X and millennial women was to get so thin as to disappear. The male ideal was to get “swole”—that is, noticeably and admirably muscular. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary added “swole” in 2019, as an old word that goes back to Middle English that gained new meaning in the late twentieth-century in lyrics by rappers like Ice-T and 2Pac and in bodybuilding circles. As a fitness culture usually on the margins of sport, some of bodybuilding’s training norms have now become more mainstream, including gallon-a-day hydration, sky high protein intake, creatine supplementation, and lifting heavy weights.

I observed these oddities up close in college, when my boyfriend (now husband) trained to compete in the 2004 Mr. Oklahoma competition. He won the lightweight class, a notable achievement — but it only compounded the body issues that plagued him as a millennial man.

As Anne wrote, “a vernacular of deprivation, control, and aspirational containment” molded young Gen-X and millennial women’s strained body experiences into unquestioned norms. There was a similar but inverted vernacular for men, marked by frenzied protein consumption and frantic muscle growth. And while postfeminism was a complicated lie, things were messy for men coming of age in this era, too. They didn’t suffer from the same patriarchal oppression as women, but they weren’t free from it either, and it wasn’t considered “manly” to ever talk about it.

Just as a thin body with perky breasts isn’t physically possible for every woman (um, most women?), a towering height, six-pack abs, a big chest, bulging biceps, and jacked traps aren’t in the cards for every man, no matter how many hours he spends in the gym. And yet those ideals, those totally-unreasonable-and-yet-seductively-convincing expectations, have been everywhere for men of our generation, shaping what they ate, how they trained their bodies, and how they tried to exist.

Gender is a big part of this story, but not all of it. These body ideals represented a narrow and prescribed identity, especially when it came to sexuality and race. The presumed heterosexuality of these body ideals for men (and for women too) hurt LGBTQ+ folks. There was no space for people with disabilities. And the hierarchical whiteness of these ideals viewed muscular Black celebrities—like Will Smith or LL Cool J or 50 Cent—through a limited white gaze. White audiences and commentators also cast the outstanding Black male athletes that shaped millennials’ childhood views of sport (Michael Jordan, Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders) as “naturally” gifted on racist terms.

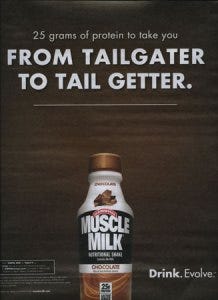

Anne reminded us of SlimFast, whose commercials really were everywhere, encouraging (mostly) women to replace their meals with sad canned shakes. The product name is transparent, promising to help you become thin, and quickly. The gendered counterpart to SlimFast was Muscle Milk; I remember an ad that read “from tailgater to tail getter.”

Muscle Milk launched right around 2000, as a whey protein shake to help drinkers get big. It met the needs of bodybuilders and other strength athletes, but it also tapped into the turn-of-the-millennium high-protein, low-carb diet zeitgeist of Atkins, South Beach, and Zone. As Casey Johnston profiled for Eater, Muscle Milk really took off in 2004 when they started selling ready-to-drink products at spots like GNC, in addition to big ol’ tubs of the stuff. When “yogurts for men” launched in the 2010s, it wasn’t to compete with other yogurts; it was to take on Muscle Milk. Supplements, particularly for protein, are a multi-billion dollar business that reshaped millennial men’s diets in their teens and college years that is now restructuring the food industry. Look around. Shakes are everywhere. Specialists now worry that men replacing more and more meals with protein shakes constitutes disordered eating behavior, even a formal disorder called protorexia.

But if Muscle-Milk-is-to-SlimFast, WTF is the millennial teen boy equivalent of Seventeen magazine? Despite the history of comic books, the periodical industry believed that young men didn’t buy magazines unless they were just about sports. Sales failures tended to support that. Sassy’s publisher launched Dirt for teen boys in 1991, but it shuttered in 1994. In 2000, Times Mirror tried again with Stance, while Rodale (which publishes Men’s Health) launched a teen-friendly version, MH-18. "A lot of teen guys have been reading Men's Health and they write letters to us,” the editor explained in 2000. “They ask acne questions or 'Can you give me a workout that's designed for me? I'm not concerned with losing my belly, I'm concerned with building my biceps.'” (MH-18 folded in 2001 after just five issues).

Teen girlhood is a site of constant contradictions. It’s celebrated and derided, sexualized and overprotected. But teen boyhood barely exists. It’s viewed as a life chapter to rush through in order to reach manhood, the stage that matters. Teen magazines did (and do) little to protect young women from the full brunt of disordered body content found in women’s magazines, but millennial teen boys didn't even have “age-appropriate” outlets. Young men’s body instructions more likely came from men’s magazines, where their young anxieties weren’t addressed.

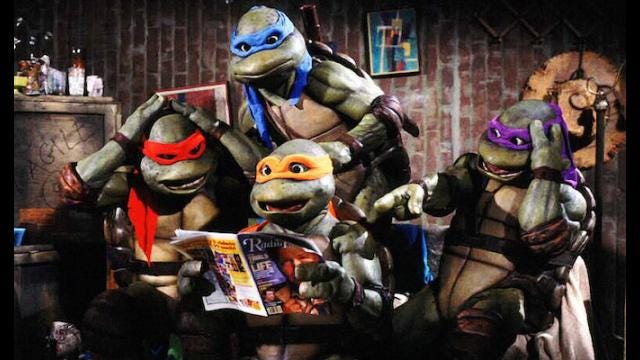

Social norms force women to always aspire to youthfulness, to defeat aging skin and fight off cellulite, but society pressures men to banish their boyishness. Millennials were the first generation to grow up playing video games, and there are real reasons adult millennial men still play them, collect toys (and watch TV shows about them), and why ‘90s nostalgia has staying power. And just like Barbie for girls, millennial toys intended for boys sent messages about ideal bodies through the muscles of GI Joe, He-Man, M.U.S.C.L.E. figures, and even the non-human Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, who boasted big delts and striated quads.

Traditional tough guys from an earlier era, like John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, embodied a strong physicality but not an outright muscular one. And they mostly kept their clothes on. Hard body action hero films emerged in the 1980s, but proliferated further in the 1990s and 2000s as millennial men grew up, including in TV movie re-runs. What’s more, popular hard-body franchises circled back with numerous sequels that kept muscular and relatively age-defying men’s bodies front and center.

Consider: First Blood (the first Rambo film starring Sylvester Stallone), which came out a touch too early for millennial viewers in 1982 — but was followed by two sequels in the 1980s, along with installments in 2008 and 2019. Terminator (starring former bodybuilder and always muscular Arnold Schwarzenegger) came to theaters in 1984, but it’s followed by Terminator 2 in 1991 and franchise installments in 2003, 2015, and 2019. (Don’t get me started about how these two bodies collide in The Expendables in 2010, 2012, and 2014.) The same stars that planted seeds of both aspiration and insecurity in millennial boys won’t let up as millennial men’s bodies age.

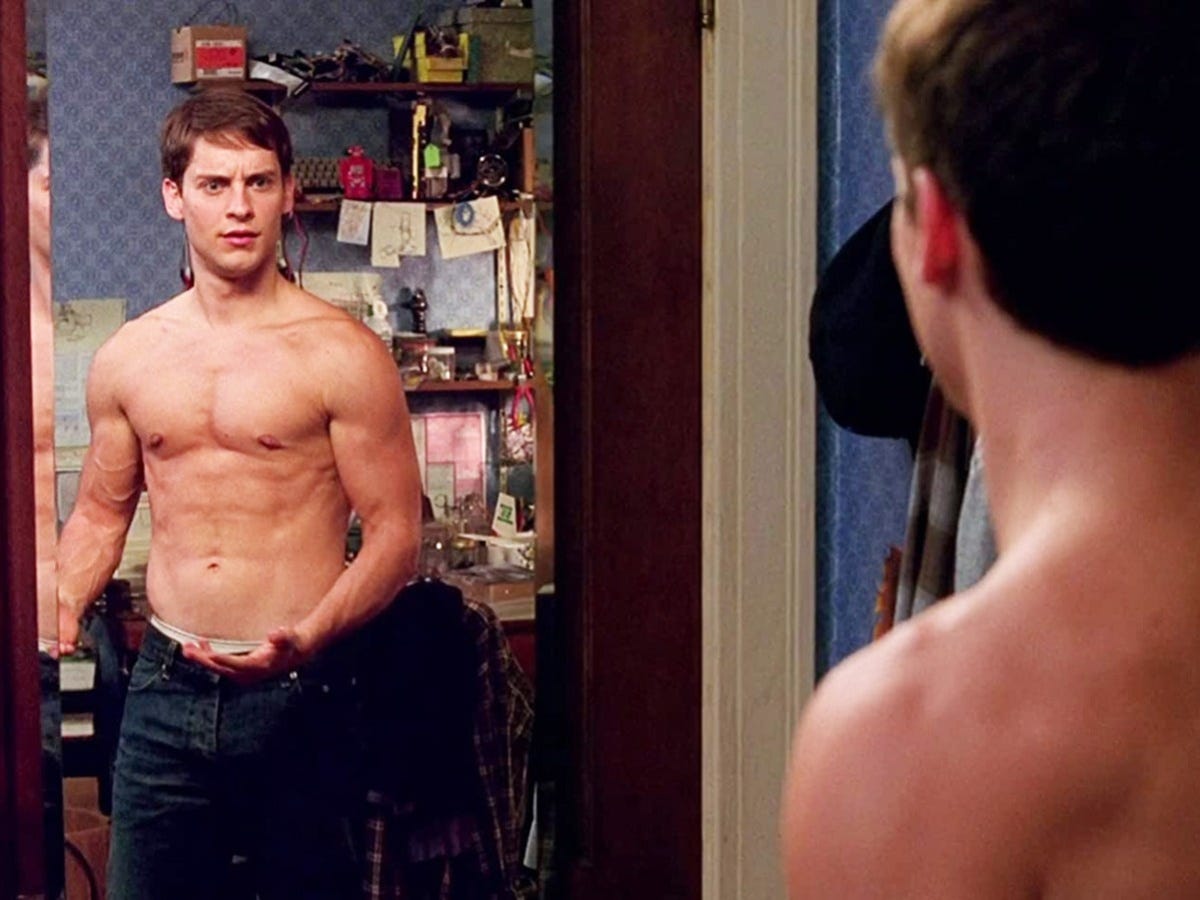

The explosion of superhero films, particularly within the Marvel Cinematic Universe, didn’t help either. I clearly remember the suddenly present and visible chest and abs of Tobey Maguire in the 2002 reboot of Spider-Man—an actor up until that point known for sweeter (and clothed) roles in films like Pleasantville and The Cider House Rules. While a far cry from the superhero bodies to come, Maguire’s physical transformation remains in millennial men’s memories thanks to media features like this from 2020: “Here’s Tobey Maguire’s Workout Plan Which Made His Spider-Man The First Ripped Superhero Ever.”

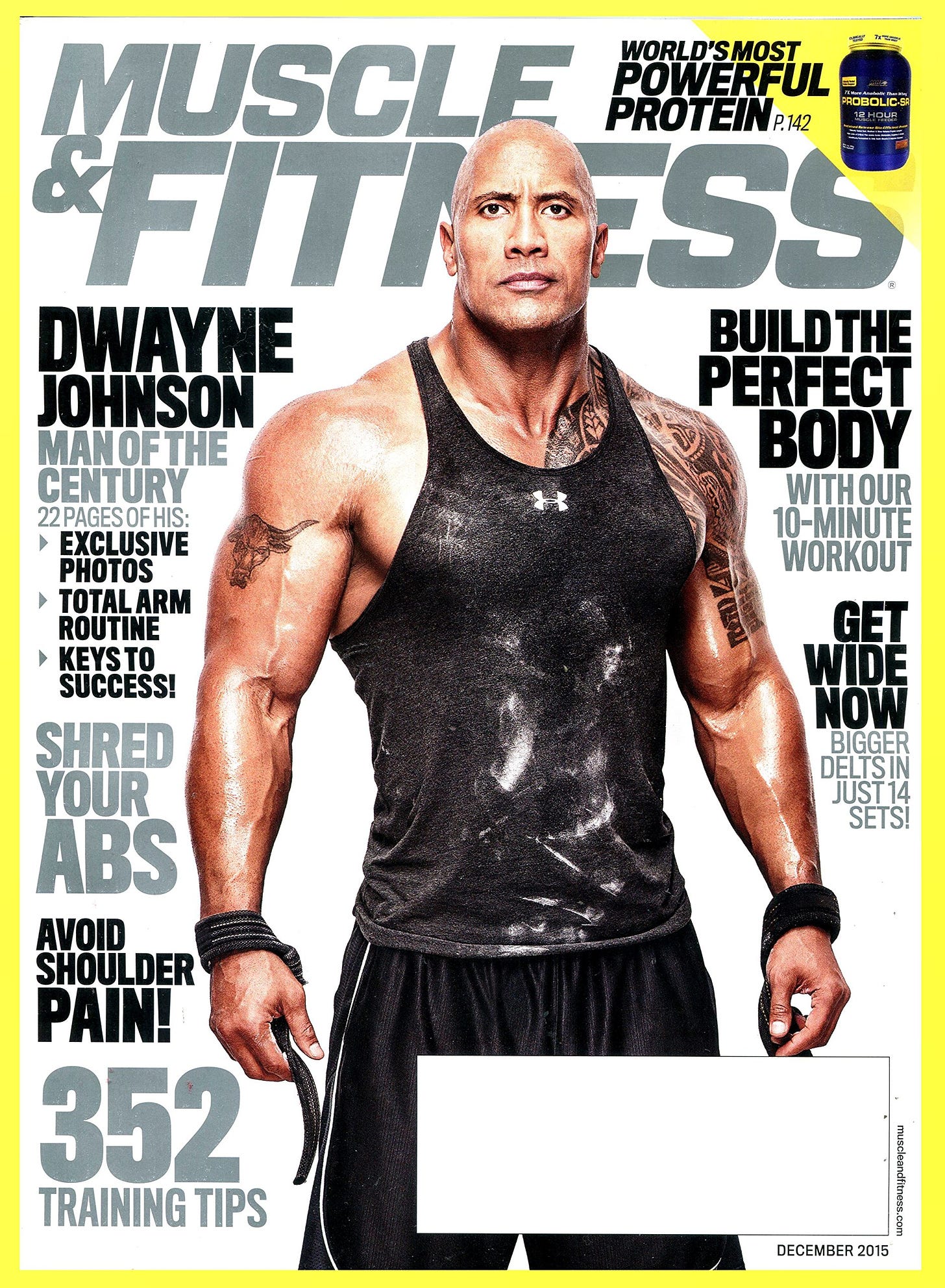

Really, though, if there’s a millennial film franchise obsessed with mirror muscles, it’s Fast and Furious. When it came out in 2001, Vin Diesel was the muscular lead alongside pretty boy Paul Walker. The internet is still clogged with features on how to get Diesel arms. His bulk was only convincing until Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson joined the cast in the fifth film, exaggerating the ideal masculine body type even further. Next to The Rock, Diesel looked like a kid playing around with his dad’s weights in the garage.

When I brainstorm with my students media examples of “a real man,” The Rock usually comes up. His brand of masculinity was first forged on the gridiron and then in the sports entertainment world of professional wrestling during a millennial resonate “Attitude Era” during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Today he’s considered quintessentially masculine for his lofty height and very muscular physique (much bigger and leaner than earlier in his career), while also seeming like a very nice guy.

But as media theorist Alix Beeston points out, he, along with other Black actors like Terry Crews, “don’t have much choice but to be the good guys, because their awe-inspiring bodies carry the weight of decades of negative depictions of black masculinity.” What’s more, she writes that, “Johnson’s films studiously avoid mentioning his race, but his blackness marks the outlines of his star persona — as it is shined up, made benignant, in both senses of the word, benevolent but also beneficial.” Dwayne Johnson’s ever-expanding media image captures the role of race in masculine body ideals, which by and large represent white (and usually exceedingly straight) men. Millennial pop culture posited whiteness as a key ingredient of ideal masculinity, a power negotiation that’s continously played out within The Rock’s muscular form.

And then there’s Brad Pitt’s abs. In an interview with Conan O’Brien, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia star Rob McElhenney recounts approaching a trainer with “an ideal male body that I want to go for.” The trainer’s response: “Don’t tell me what it is. Every dude for the last twenty years that wants to get into shape comes in and says the same thing...Brad Pitt, Fight Club.” In the way Anne and I can immediately conjure Britney’s abs, Brad Pitt’s physique is similarly burned into many millennial men’s minds, not just for its lean muscularity, but for all the ways Fight Club (published in 1996 and released as a film in 1999) represented masculinity.

Beyond muscles though, men’s body anxiety centers on a particular anatomical feature—the penis—and for millennial men, again, these fears may be worse for real reasons. They’re arguably the first generation to come of age with online pornography widely available at the click of a button, even if with slow-ass dial-up. (When guys my age arrived at college and realized how lightning fast the T1-line speeds were, the first thing they downloaded was porn.) What’s more, millennial men also grew up newly surrounded by marketing messages about erectile dysfunction. Viagra was approved by the FDA in 1998, when I was in middle school. Given America’s allowances for direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising, millennials are as aware of potentially malfunctioning penises as we were conditioned to fear Y2K and quicksand.

I could go on forever, so I’ll switch to a bulleted list of how other aspects of the cultural landscape shaped millennial men’s body issues:

The famed 1992 Calvin Klein underwear ad starred Kate Moss, providing an impossible ideal for millennial women during their formative years, but Mark Wahlberg offered just as impossible an ideal for men, five years before he’d play a massively hung porn star in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights.

UFC 1 took place in 1993 with mixed-martial arts fights gaining polarized attention in the 1990s (John McCain tried to prohibit the sport for its perceived violence) and increasing popularity in the 2000s and beyond. (While we’re on the topic, read Jenn McClearen’s new book, Fighting Visibility: Sports Media and Female Athletes in the UFC.)

Rogaine became available over the counter in April 1996. I can’t tell you how many ads I saw as a teen. Rogaine also popped up in a fan favorite episode in season 4 of Sex and the City.

In 1998 Mark McGwire broke the home run record with his massive forearms and biceps, followed by similarly huge Barry Bonds; they were also the face of suspected steroid scandals well before Lance Armstrong, who won the Tour de France seven times from 1999 to 2005, in a leaner body than typically idealized, but still with superhuman strength and endurance.

“The New NFL”, more media brand than just a sports league, blew up in the 1990s and 2000s, increasing the media presence of football, cementing its prowess as America’s favorite sport and claiming significant space for shaping masculine social norms.

Axe body spray arrived in 2002 (and created a bonkers legacy)

I remember a guy friend telling me about dating women after college who followed the 6-6-6 rule, which reemerged in recent years on Twitter: they only dated men who were at least six feet tall, had six-pack abs, and earned at least in the six figures.

As Anne pointed out, the Abercrombie aesthetic, but for men it was shirtless! And not just in ads; he came to life in the mall.

Gen Z women might not understand why millennial women’s relationships with our bodies are so destroyed, but I wonder if Gen Z men might get it, at least a little bit. Shirtless Abercrombie boys are a thing of the past, but muscle-bound messaging to men hasn’t faded to the same degree that negative-calorie-food endorsements in today’s supposedly more enlightened wellness culture.

The men’s media space has transformed — but alongside coverage of trans rights and addiction recovery that you never would have seen in the 2000s, you still find articles to “pack on pounds” and “get jacked.” Media culture traumatized a generation of women in startlingly specific ways — but millennial men didn’t make it out unscathed either. ●

Emily Contois is the author of Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture. She’s currently working on her second book, which explores how brands convince everyday consumers to eat, train, and work “like an athlete.” Follow her on Twitter here.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version, which allows me to pay a very good rate to writers like Emily. Another perk: weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. Last Friday’s thread was the return of the advice thread, and it is yet again at over 1000 comments.

The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here. The post-newsletter discussions, particularly this past week, have been so fortifying. This Thursday (5/27), Delia Cai and I are interviewing Terry Nguyen at 2 pm PT / 5 pm ET on “the case against being a real person online” — come listen or hang out in the chat room or lurk!

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I was talking about this topic with two male friends recently. We had all re-watched Gladiator for a movie night, and one of the things that stood out to me is that in 2000, Crowe's body was considered muscular but not...overbearing in its aesthetic. It was a fit body. A body meant to do work, not be possible due to dehydration, endless hours in the gym, or, because we all know they use it, testosterone. Both my friends talked about how inadequate they felt compared to current male swole standards and how a body like Crowe's isn't seen as enough has an impact.

We don't have that anymore for men now unless you look like you've superglued sixteen hotdogs to your stomach and haven't been able to fit through a doorframe since puberty; you're disgusting, slovenly, undisciplined, you're like a woman. Swole culture is just misogyny in a different package, the need to be so diametrically opposite to women that we've essentialized and aestheticized what it means to 'be a man.'

This issue makes me think of Kumail Nanjiani, who swiftly went for being celebrated for his transformation from softish need to jacked Avenger Bod to being mocked for looking TOO jacked (possibly by enhancements, or not.) Like women, there are unwritten rules for guys about how the transformation happens, if it’s “honest” or not.

If we could post pictures on SubStack comments, I would include some photos of the way Spiderman and Batman are portrayed in my kids’ books and action figures. Spider-man in particular— if he’s just a teenage boy under that suit, how come his thighs are twice as wide as his calves?