The new episode of THE CULTURE STUDY PODCAST is here — with me, Strict Scrutiny’s Leah Litman, and our very own Melody Rowell going *deep* on all things Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce.

We talk about the folklore Emily Dickinson theory. We talk about the tall-girl-ness component. We wonder: does Harry Styles indeed suck. We talk about how we ourselves feel about the end game vibes of it all…..and we answer so many of your very good questions. Even if you don’t consider yourself a Swiftie, you will appreciate this conversation. Listen here.

It’s the end of the year, which means it’s time for endless appeals to 1) spend money on each other and 2) as an afterthought, give money to an organization that helps people who have less money to spend on each other. Anyone in the non-profit space will tell you how crappy December is: how essential the donations that come in right now are to organizations’ yearly budgets, but how stressful it is trying to make sure they do arrive.

I do my small part to try and alleviate that stress by doing what I’m told: putting my donations on monthly auto-pay instead of giving in one chunk. But the surge of increasingly plaintive emails is a reminder of how bizarre philanthropy has become. How intermingled it is with the ethos of capitalism, how much the appeals have come to hinge on a productivity-tinged mindset of maximizing dollars, how far we seem to have traveled from the original definition of the word — philanthropy as a love of humanity.

In her new book, Amy Schiller argues for a more ambitious definition of philanthropy by arguing for a more ambitious understanding of humanity — one that includes, as she told me, “our capacity to flourish, to create, to imagine and collaborate with others.” What you see in our conversation below is a manifestation of that belief — and an interrogation of the current norms of philanthropic giving.

Why does the RED campaign and others like it feel so icky? Why does Effective Altruism piss you off? What does LeBron James’ foundation get wrong? What’s missing from MacKenzie Scott’s strategy? Schiller tackles all that and more — and you’ll never look at the appeal email in the same way again.

You can buy The Price of Humanity: How Philanthropy Went Wrong — And How to Fix It here — and find more about Amy’s work here.

Let’s start the way your book does: with the fundraising appeal. What are the tropes, and why is it a good place to start when we’re talking about some of the foundational flaws in the way we think about philanthropy?

First, I was striving for familiarity – a lot of the book is pointing out the ubiquity of philanthropy, the norms we’ve been immersed in and absorbed and maybe even found troubling or bizarre without quite knowing why. So the idea is to introduce this abstract term, philanthropy, at the level where we frequently engage and encounter it: the appeal letter.

The main tropes are objectification, cost-effectiveness, and self-interest for the donor. Objectification covers the reduction of people to their suffering, their desperation for the most basic items necessary to survive. This also includes a certain level of sensationalism and melodrama – the pleading eyes, the alarmingly thin limbs, the Sarah-McLachlan-with-dogs of it all. This sensationalism is emotionally arousing, and then alchemized into a financialized moral calculus. Cost effectiveness is the “for just a dollar a day” device, what I call “the exchange rate for generosity.”

Self-interest for the donor happens on a couple of levels: one, the cost-effectiveness means they get to feel heroic and/or virtuous for cheap. Second, that your gift will generate the greatest return for you, be it in salvation points or in the assurance that you have chosen wisely, or the satisfaction of seeing some big effect that you feel you personally made possible.

I introduce these tropes in a cheeky way, with a sort of fundraising-appeal Mad Libs, to show just how predictable and formulaic these appeals are. Right from the start, I want people to think about how the scripts of giving have conditioned them to see other people and themselves. What power dynamics, what patronizing assumptions about people who need help, what promises of efficacy and superiority — the donor’s superior virtue, the organization’s superior efficacy, the way that becomes a proxy for a donor’s intelligence — become obvious on close reading?

The book contains a bold, bracing, provocative argument: that this activity that literally means love of humanity has, in some ways, dehumanized others….and normalized expectations that are way below human flourishing for them. So I wanted to warm readers up by just holding up a mirror and reflecting the language back, so that they are open to this big challenging argument.

For a little more table-setting: what’s the “return”-based approach to giving? Do you think of it as the same (or in the same general philanthropic boat) as effective altruism? I’d love to hear you connect the dots a little to productivity culture and why philanthropy often falls apart when it treats human beings as capital instead of, well, humans.

Effective Altruists evaluate charities with very utilitarian metrics: their impact has to be quantifiable, and it has to strive for volume over depth. If more people get a minimal improvement, that’s far better than fewer people getting a deeper, more holistic benefit.

One of these metrics is QALY, “quality-adjusted life years.” It’s used in a lot of public health and other settings, but in Effective Altruism it becomes a kind of absolutist lens through which all human benefit is defined as whether a person gains more healthy and economically productive years of life.

That’s why I consider Effective Altruism to be more like “global labor force and population management.” Its “altruism” only seeks to maximize the number of economically productive actors in the world. So the idea of “return on investment” is at its full expression here — human beings need to provide the best bang for the buck, the best return on an up-front benefit (say, a bed net to prevent malaria that then means you don’t die from that disease and can keep working). Keeping people alive and economically productive is not an act of love for their humanity — it’s instrumentalizing people the way capitalism always does, defining our value by our future economic potential.

If we go just slightly farther back in history, this ROI mentality has a precedent in institutions like the Robin Hood Foundation, which prides itself on using the methods of financial investment to evaluate whether nonprofits are generating sufficient benefit. They evaluate grant recipients based on a “Benefit-Cost Analysis,” which includes a very similar set of priorities: estimated number of years of extended life, and per-person lifetime earnings.

So philanthropy under this rubric is not about creating sanctuaries from or alternatives to the demands of capitalism. The benevolence, if you can call it that, is in giving people from the underclass a chance to succeed by its rules. With, of course, very patronizing and constraining surveillance from the funder. It’s neoliberal brainworms all the way down.

When I think of “how giving became shopping,” I often think of Gap’s RED merchandise — part of a campaign to raise HIV/AIDS awareness featuring many celebrities, but none more prominent than Bono. What felt weird and hackneyed then now feels, well, commonplace. Cloying, superfluous, meaningless, a mode of brand-management — but very rarely about actually serving people.

It’s celebrity faces of philanthropic campaigns, it’s “10% of your purchase goes to [INSERT CAUSE],” it’s “for every shoe bought we plant a tree in the Rainforest,” but it’s also programs like Amazon Smile and “do you want to round up today to fight hunger” and GoFundMes for healthcare costs and DonorsChoose and even platforms like Kiva that help you choose the “best” charities. How did we get here, and how do we move away from it?

A lot of how we got here was in the flattening of everything into a market transaction. We lost language for understanding human relationships that didn’t somehow satisfy the demands of economic efficiency.

Your list is all absolutely one constellation, but let me trace a couple of shapes within it.

The shopping stuff – that’s about aspiring to be a business, something that earns revenue instead of just asking for donations. You don’t want to be some chump just asking for help. You’re an entrepreneur! A visionary! The founder of (RED), Bobby Shriver, said to the New York Times, “we want people buying houses in the Hamptons because of this thing.”

I cite two anthropologists, Jason Hickel and Arsalam Khan, who describe this trend as the purchasing of a feeling: buying our way out of discontent with capitalism, buying the illusion that we and our world can be redeemed, with the very tools that are causing its degradation.

Around the 1990s there was this feeling that capitalism could, like, save the world, or some other nonsense. After the fall of the Soviet Union comes an unstoppable capitalism supremacy narrative, with global trade and emerging markets going absolutely wild and huge technological strides. The hubris skyrocketed and it all seemed to be in reach, the harnessing of resources and the total potential labor force and somehow organizing it for maximum prosperity.

Consider the emergence of tech wealth. If the script is ‘my brain just invented a thing that connected the world,’ you just might think, ‘let’s do that again but for a different big, seemingly impossible thing, like eliminating malaria.’ You will likely see it as a challenge that can be solved with right thinking, right design, rather than the result of a power structure that structurally devalues others.

Now, the GoFundMe and DonorsChoose thing is closely related, but it gets its own throughline. These platforms emerge to seemingly supplement gaps in the public safety net for things like education and health care. But instead, they’re in a kind of enabling feedback loop: instead of your taxes ensuring that kids have desks and cancer patients can get chemo treatments, you (the wise and benevolent consumer) get the frisson of having made those things possible. The outrage of reduced public investment gets softened by the all-too-human pleasures of buying those things discretionarily, a la carte, according to your preferences.

I especially appreciate this quote from another philanthropy researcher, Vinnci Li: “consumption-oriented philanthropy…emulates the consumer shopping experience by reformatting aid recipients…into symbolic commodities.” That comes from her article about a “gift catalog” from a huge humanitarian organization based in Canada, which prices things like “save a child soldier” or “help sexually exploited children,” as if those things should feel the same as buying a fleece jacket. She beautifully sums up two of the big trends we’ve talked about so far: the objectification of others in fundraising language, and the reduction of everything into a capitalist experience, a form of shopping or investing.

Lastly, the celebrity thing — we have such an ambivalent relationship to celebrity, we need them to also be virtuous, perfect but relatable. The obvious example of a celebrity who has mastered this is Taylor Swift. I point it out because philanthropy as part of your celebrity brand reconciles that ambivalence about celebrity glory with the egomania of wanting to save the world. The performance of social consciousness is a legitimizing force: it validates your worthiness and character, whether you’re Bono or some rando with a trust fund.

The chapter on MacKenzie Scott (and the contrast to Andrew Carnegie) really reframed some of my thinking on her style of giving. What are “the limits,” as you write, “of cash giving as a rebuttal to capitalism”? And how was Carnigie’s approach different?

I’m so glad you asked this because this argument is one of the biggest risks I take in the book.

Here’s the main contrast:

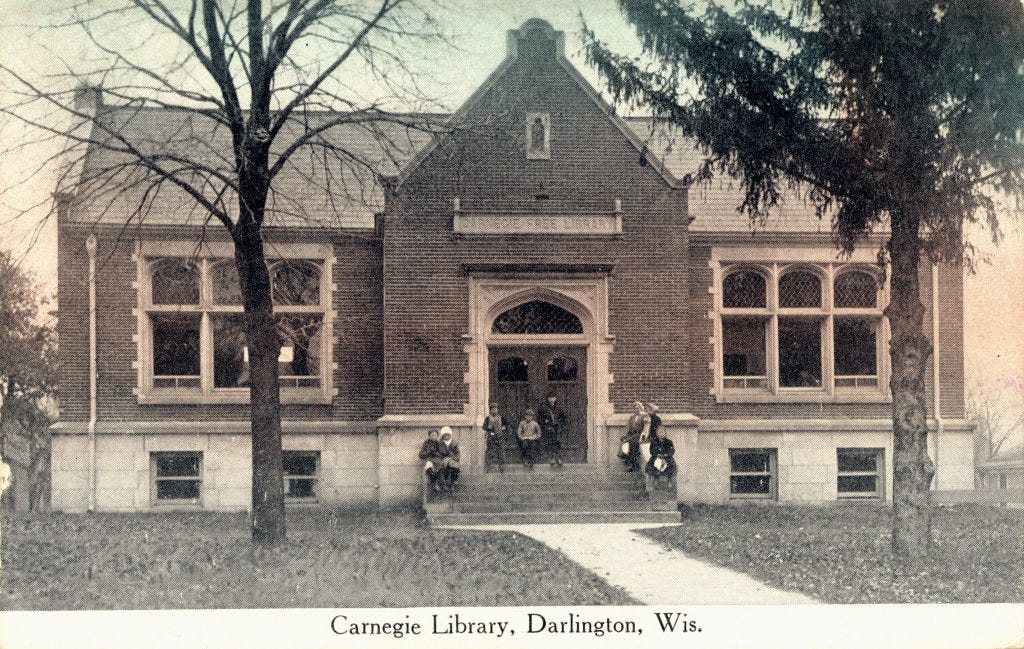

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy built, first and foremost, a network of library buildings across the US (and internationally). He did other stuff, but a lot of it was capital projects like schools, swimming pools, that sort of thing.

MacKenzie Scott, on the other hand, is giving away huge sums of cash on a semi-regular basis. She is not overseeing construction, founding any new institutions, she is giving a huge swath of nonprofits a major cash infusion, no strings attached.

Now, there is a LOT to applaud about what Scott is doing. Compared to her peers in the billionaire class, she is a breath of fresh air, mainly for willingness to cede control over the money, to place no demands on these organizations to accommodate her. To actually center others, rather than herself.

But even with all of that, what I came to conclude is that Carnegie’s giving may have produced a better OUTCOME than Scott’s will.

There are a few threads to this. One is the sheer endurance of what Carnegie’s giving produced. Those libraries still exist, while the cash will dissipate, albeit into important uses. I see those libraries, those buildings, as bulwarks against the totalizing ambition of profit-seeking. Every other week there’s a tweet that says, we couldn’t convince people to build libraries today if they didn’t exist, and there’s something significant about creating things that really endure over time.

Second — and this is really subtle, because I’m all for giving people and organization money, no strings attached. With that said, MacKenzie’s cash giving does not directly confront the power structure that produces racial and economic injustice, which she names as the main concern. There doesn’t appear to be a strategy around policy change, or working conditions, or anything further upstream. The cash giving operates as a settlement. It alleviates damage, but doesn’t create new centers of power. Her own statements speak to systemic injustice, but somehow her philanthropic ambitions stop at wiping her hands of the money. Which would be fine if it was at least partially focused on building power, i.e. funding workers’ strike funds. Amazon has one.

So what brings these two things together? Libraries are these enduring spaces that are also challenges to the capitalist mentality. Again, how often do we hear, libraries are some of the last places people can go to just *be,* without having to buy anything. You can access books without having to purchase them! They are sanctuaries against the ambitions of capitalism that would commodify every place and every experience for profit.

(There is an irony here — Carnegie, the enthusiastic capitalist, is the one who enabled the *decommodification* of books, while Scott, who is much more ambivalent about capitalism and is herself a novelist, has billions because of a business whose origin is…commodifying books.)

And you know what makes libraries endure, what gives them their relevance and the loyalty of so many? They are often beautiful spaces. That was something Carnegie wanted and had the money and stature to make happen! He wanted them to be “palaces for the people,” and because of that, everyone, from an unhoused person to an affluent one, finds them comfortable, soothing, engaging places. That’s also radical! That everyone deserves beauty, everyone deserves to be in a space that confers dignity. To me, that’s the highest form of philanthropy: a true love of humanity.

You initially emailed me about the book because you had observed (correctly) that I am obsessed with LeBron James’ work in Akron, starting with the I Promise School and spiraling out from there. When I first heard about the school, I think I waited with bated breath for someone to point out something that his foundation was doing wrong, or something that was off…..but I just keep reading and he just keeps adding programs and things just seem to be really awesome? Tell me, to your mind, what makes James a different sort of mega-philanthropist — and what other people with his means could learn from him.

The thing that made me want to write about LeBron is the bikes (and helmets) he gives to every kid who attends the I Promise School. More specifically, his *explanation* of why he gives the bikes. He described it as “a way to let go and be free.”

I honestly get choked up whenever I think about it. Tons of donors build schools, or other education nonprofits. So many of them — especially ones that serve Black children — emphasize how structured they are, how much the kids’ performances will improve, their academic success. I get why that’s important, but it’s so discipline-oriented. It is so rare to hear someone talk about wanting kids to feel free. Something you can’t track, that doesn’t conform to those productivity and performance standards. Just freedom, life on one’s own terms, exploring the world.

Watch the video of LeBron speaking at the opening of the I Promise school, it’s on YouTube. He’s human and grounded and connected to deep emotional experiences. He doesn’t traffic in weird analytical robot speak about measuring impact or whatever, I think he sees people — both as a player and as a philanthropist — and I wanted to celebrate that.

A couple of other elements: LeBron is very locally focused, and he takes pride in his local commitment and roots being in Akron, rather than a more glamorous town or something nationwide. I Promise is also a public school, overseen by Akron public schools and with a collective bargaining agreement. It’s huge for philanthropic money to supplement and defer to public institutions, and very much welcome and against the grain. And like Carnegie’s libraries, his funding builds beautiful spaces that confer a sense of dignity to everyone who enters them.

If there are two things people who are not LeBron James can apply, it’s 1) connect to your human self, your community, your formative experiences and the spaces and institutions that created you as a person, and figure out how to do that for others, and 2) pursue a balance between public authority – which keeps things accessible and transparent – and private money, which allows them to embellish and enrich and help people flourish.

Because this book shifted my thinking in a lot of ways, I want to ask you: how did your shifting change over the course of writing this book?

My research trip to Paris for the cathedral chapter — which examines the blockbuster fundraising around Notre Dame’s fire and restoration — really refined my thinking and gave me this irreplaceable sense of history, texture, the sensory and emotional power of a place, all of which was a new register of storytelling that I didn’t expect to reach with this book. It allowed me to expand the tone to be more poetic, more literary, to go all in on my advocacy for the sacred, the magnificent, as a worthwhile aim for philanthropy.

Talking to French scholars Anne Monier and Nicolas Duvoux gave me a deeper sense of why that was such a big and disruptive moment: big philanthropy came on the scene in a way that was unprecedented in France. Just walking around the site, seeing how people congregated around it, even as a construction site, was so powerful. I could see why the city streamed into the streets the night it burned. And so going to do that research helped me hold the two truths — and stay patient as I figured out how to do justice to both.

That duality is really the heart of the book: we need political justice AND philanthropy that builds things that endure and nourish us outside of the framework of direct political struggle or social crisis. The latter takes a lot of patience and clarity. But I saw and felt what it meant to connect to something magnificent. That’s why I wanted to write a path forward for philanthropy, so it can preserve those domains of experience for all of us, to fight off our commodification and keep us all human. ●

Amy’s coming on The Culture Study Podcast to answer ALL OF YOUR QUESTIONS about sketchy (or promising!) celebrity philanthropy. We need your questions to make a good episode — you can very easily submit them here.

Appreciate this interview. I will put the book on hold, it’s very relevant to my work.

I do want to say that I think a lot of the “average” employees (midlevel, low level, and even some c-suite!) at philanthropic and nonprofits organizations do think about these issues and have been talking about these things for a while. (Folks should check out Vu Le’s amazing Nonprofit AF blog — he would be a great interview for culture study!)… the forces that we who envision a different way forward are working against, though, are as is illustrated in this interview, systemic and hard to move the needle on.

And I appreciate the point about Mackenzie Scott’s efforts not moving the needle on public policy or systemic change, but philanthropists and organizations also come in for criticism when they try to do that (for example, the Red campaign and related One campaign are about advancing funding and advocacy for policies to end poverty and HIV, ultimately working towards achieving certain sustainable development goals)…. So it can feel like there is no winning.

I don’t know. I got into this work because I was once a bright eyed, bushy tailed college grad who wanted to do work that aligned with my values. In some ways it’s never felt like a more hopeless time for those of us in these fields — individual giving is decreasing, governmental support for global health and development causes is shrinking as resources are redirected domestically and also to global conflicts… the author is right that things are not working. But it can be hard to keep your head up sometimes as we try to work towards a better system!

If MacKenzie Scott built a network of public buildings/institutions across the U.S, like Carnegie’s libraries, wouldn’t she be criticized for deciding what communities need, versus supporting the local communities in their existing infrastructures and deciding for themselves where money should go? I don’t run to defend billionaires from critique, but I do sometimes feel like no matter what MacKenzie Scott does with her money someone somewhere will go “aha! here’s why it’s wrong though!” It’s hard for me to imagine her saying “I’m going to give cities these big buildings that will be a positive value-add because they’re publicly accessible and beautiful” and people not thinking that’d be wrong. I think she’s operating in such a wildly broken system (capitalism in the U.S) and doing something really powerful and positive with her totally unearned privilege. People should get universal basic income, and have enough food to eat without individuals donating to food banks, and everyone should have free healthcare, and everyone should have safe homes to live in. Dogs shouldn’t be euthanized in overcrowded shelters made of concrete. Our government fails us. Billionaires shouldn’t exist. I think Scott giving away her money no strings attached is the best thing she can do.

Edit: an additional thought is that I think it’s a really bizarre argument to make that Carnegie’s outcome/impact was superior to what Scott’s may be, after just critiquing the very cold hard metrics of movements like effective altruism. Do we really want to measure philanthropy by outcome and not by process? It is Scott’s process that has been so revolutionary in philanthropy. This critique grounded in the comparison to Carnegie just feels really reaching to me.