The Quiet Glory of Aging into Athleticism

I wasn't ready to be an athlete, in any capacity, as a adolescent or young adult. I am now.

In elementary school, I was that kid who figured out how to hide behind some random outdoor building to skip doing laps 2 and 3 of the mile. During my short and undistinguished soccer career, I once locked myself in a bathroom to avoid going to a game. We only had right-handed mitts for P.E., and I never really learned how to catch (or throw) a ball. I really liked my high school history teacher, but not nearly enough to believe him when he told me that I should consider joining the track team he coached. I was, as we say now, a real indoor cat.

This isn’t entirely true — I loved to ski, and camp, and water-ski. I went on rafting and backpacking trips. But not-being-athletic was the story I told myself about who I was, what I liked, and what my body wanted to do. When I first started “working out” in high school, it was always purely utilitarian and utterly joyless: my internalized millennial fatphobia disciplining me vis-a-vis Jane Fonda step aerobics tapes and the elliptical.

I think I found slightly more pleasure, or at least mental space, from running when I was in my 20s. But exercise was still rote — a thing I did because because body regimentation was part of the never-ending work of what I understood as feminine beauty. I never thought of it as a sport, or of myself as an athlete. There were no elliptical Olympics. I was just checking a box.

This mindset began to change, very slowly, in my early 30s. I began spending less time in the gym and more time running the wheat fields around Walla Walla, where I was working as a professor before leaving academia. My best friend had started training for a half-marathon, and because, to be honest, I didn’t like her doing things that I didn’t also do, I thought I would as well.

At that point, I’d run six miles before, maybe seven, but the first time I worked up to ten, I felt like I was the Queen of the Universe. I felt like I could lift seventeen skyscrapers, like I could push myself past mild discomfort into a space of new capabilities.

I ran that half marathon. The next year, I ran another. I got rid of my training watch when it pushed me too hard and I injured myself, but I was still mired in that understanding that the only way to run was to try and run all the time. The suggestion that strength training, like actual cross-training, particularly strength training, might actually make me a better runner? Blasphemy. All I understood was cardio. In 2020, I was training for my first marathon and not feeling great about it when the pandemic hit, and then everything was canceled and I got really into Peloton and every summer was smoky and I started wondering if maybe I was done running distance forever.

But something interesting and unexpected happened when I started training this Spring for my second Ragnar relay. All those pandemic hours spent actually listening — to Peloton instructors, to Maintenance Phase decoupling health and body size, to Power Zone training that underlined the ways rest was as important as exertion — they rearranged something fundamental in my head. When someone tells you you’re an athlete every day for two and a half years, at some point you start to believe it.

How is it, at age 41, that I feel like my body can do more — and that I can take more joy in it — than ever before? I’m not faster, but I’m more resilient. I’m not doing as many overall miles, but I feel stronger. I love it more, and more feels possible. Sure, my knees are slightly more creaky, and I have to be keenly attentive to stretching and Theragunning and hydrating in a way I never was before. But exercise just generally no longer feels punitive or disciplinary. Instead, I feel something far more akin to curiosity. If part of me feels weak or tweaky, what’s struggling in other parts of my body and needs strengthening? And if I’m attentive to my body, if I’m legitimately kind to it, can it do more than I thought it could?

I had a breakthrough earlier this month, running that Ragnar that, if I hadn’t signed up with my friends two years ago, I might otherwise have avoided. (Ragnars are relays, set all over the United States, in which a team of 12 runs 200 miles over the course of a day and a half. The logistics are complicated but the organization is stunning; we ran from the Canadian Border down to Langley, WA, on Whidbey Island. It’s ridiculously and deliriously fun). Beforehand, I had trained up to 14 miles in long runs, and was slated to be one of the higher mileage runners, totaling somewhere around 20. But then two of our runners got Covid. You could essentially red shirt those team members (it wasn’t as if we were trying to win anyway) and everyone could run their original legs — or you could do what we did, and make them up ourselves.

I ended up running 27.7 miles, including a 7.7 mile hilly finisher at 1 pm on effectively zero sleep. Another woman on our team ran 30, including a killer 10 miler seemingly straight uphill at 2 am. A teammate who’d never ran longer than six miles before she started training (which included her first time over 10) racked up 14. Pretty much everyone ran farther than they’d ever run before — just with space between legs and lots of fuel. And no one injured themselves. (If you want to see more, here’s my saved Instagram stories).

We finished exhausted and glorious — and signed up for next year’s race immediately. It makes twisted sense: if anything, it’ll be easier next time with full vans. But about half the team is also now signed up for the Portland Half or Full Marathon, too, which will be many of our longest races ever. All of us, save one beast Gen-Zer, are in our late 30s and early 40s. I’ve read a lot of pieces over the years about how women come into their distance prime later in life, but I also felt like it would never apply to me.

Some of that understanding of “prime” is physical capabilities, of course, but it’s also mental, too, right? I just think women’s relationship to endurance, generally speaking, changes with time. Plus running is so much easier than so many parts of being in your late 30s. Like, if I could choose between running a half marathon and figuring out how to successfully resubmit a rejected health insurance claim….I would pick the half-marathon. Any and every day. There’s a reason our Ragnar team name was “Easier than Parenting.”

But there’s also something about pushing past your own understanding of your limitations that frees you from other arbitrary limits. As in: that was really hard. But my body can do really hard things, I know that now, in a way I never knew before, because I wasn’t actually interested in finding out.

I don’t think this relationship is limited, by any means, to running — or to physical activities we traditionally understand as “sports.” Maybe the thing you didn’t think you could do is take a short hike alone, or at the pace that feels good to you. Maybe it was that you didn’t feel like bodies like yours could rock climb, or do yoga, or lift weights. But nothing about this mental shift is contingent upon movement that is extreme.

Here’s the point where I say there’s such thing as too much curiosity, too much eagerness to push past limitations, and too little regard to the body’s myriad ways of telling you no. Recently, I’ve been learning a lot from what happened to my friend, former colleague, and ultramarathoner Brianne Sacks over the last year: “In 2021, I set the fastest known time for a woman on a 68-mile trail traverse, was the third woman to finish a 100-mile mountain race from Utah to Idaho, and ran a marathon in three hours and three minutes,” she wrote earlier this year. “However, I failed to comply with the most important rules of athleticism: respecting, listening to, and resting your body. I struggled to admit that my body deserved to be replenished after I ran it ragged.”

Bri’s still very much in recovery from the overtraining syndrome (OTS) that not only made it impossible to run, but difficult to function, full stop. And she’s not alone: 60% of elite athletes and more than one third of non-elite runners have experienced some form of OTS, and it’s particularly common in people who are always burning out in high-stress work situations.

OTS feels like a symptom of deeply American addiction to growth: that we always have to keep pushing ourselves forward, no matter the costs, to feel some measure of success, some modicum of personal and societal gratification. It’s like turning all the worst late-stage capitalism work habits onto our bodies. It makes no sense, but it makes total sense. For a lot of us, it’s the only way to go about a thing, any thing — more is more is more. This posture not only sours activities we otherwise love, but also inflicts very real and long-lasting damage to our bodies.

With all of that acknowledged: right now, for me, that’s not what any of this feels like. For one, I’m certainly not getting faster, or winning anything, or even interested in knowing my pace save to keep to slow. I also know there’s some sort of time limit on how long I’ll be able to do any or all of this, and it makes every run precious — and helps foster an appreciation for my body, a care for it, that I’ve never had before. Maybe this genre of awe is akin to what some people feel after giving birth. For the first time, I’m treating it as the remarkable assemblage of systems that it is: deserving of rest, and respect, and nourishment.

The wildest thing is that when I do that, I can actually, ultimately, run longer — and feel so much better post-run than I ever have before. It’s an ongoing revelation, really, and it’s not an accident that this switch has happened at the same time that I’m actively working to unlearn the fatphobia and workism that defined so much of my adolescent and adult life.

Of course, athletes and their coaches have known about this sort of thinking for a long time. Maybe, if I had been less of an indoor cat, I would’ve learned it as a teen. Or maybe it would have been warped by the lens of competitive organized sports, and I would’ve burned out entirely and developed even worse disordered eating habits, and never have been able to do something exercise-related without feeling like I had to win, and an old and devastating injury would haunt every movement. I truly don’t know. I do know that I wasn’t ready for sports, mentally or physically, at that age. And that right now, this year, this week, I am arriving at this feeling of a very certain sort of athleticism — of being an athlete! — entirely on my own terms.

If you have stories of your later in life relation to the concept of athleticism or sports or how your relationship with what your body can do has changed — I’d love to hear them in the comments. And as a bonus, here are….

….Some Things That Are Making Running Awesome For Me Right Now, in no particular order, with no affiliate links whatsoever, and with the full acknowledgment that you do not need a lot of fancy gear to make running awesome:

The Culture Study Discord Running-Is-Fun-Who-Knew, home to runners and run-walkers of all different ages and motivations (paid subscribers, email me if you still haven’t signed on and want to!)

These Darn Tough socks (warranty for life!)

This hydration vest

This Nuun subscription for before and after

Figuring out what running clothes you like and then buying more of them slightly used on Poshmark or ThreadUp

Figuring out what shoes work for you, buying them once a year from your local running store, and then buy them when they go on sale online when the new year’s line comes out

These Stroopwaffles for long runs

Obsessed with my paper thin Brooks running jacket that folds up into nothing (and has little snaps that you can use instead a zipper for great ventilation). Bonus: on sale.

All of Peloton’s Strength for Runners series (all available on the app)

The Run with Hal training programs for every race length on the app (free for a week, then a small fee; the app is better than the old-fashioned printed ones because it accommodates your schedule and block-out dates)

This body glide for chafing of all sorts

How Far Did I Run for route mapping, which is so superior to Map My Run I’m honestly angry it took me this long to discover it

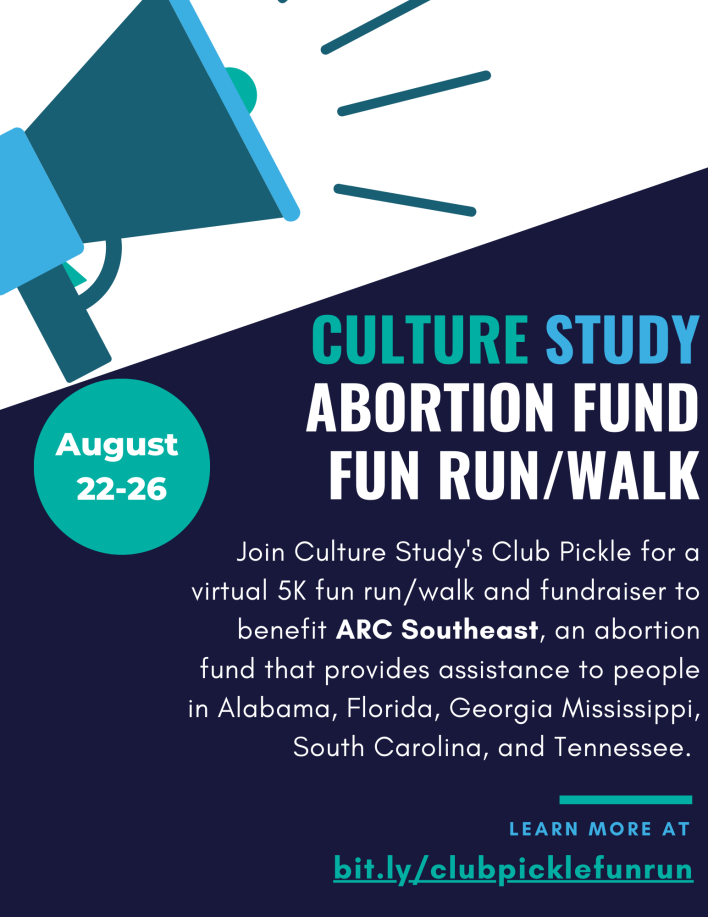

Finally, this is a great time to announce that Culture Study is hosting a virtual 5k Run/Walk benefitting ARC Southeast, an abortion fund that provides assistance to people in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. This event was imagined and will be orchestrated entirely by Culture Study members, and I’m so excited to be able to participate in it myself.

WHEN: Run, walk, or jog a 5K any time, anywhere, between August 22 and 26! If you’re part of the Discord, we welcome you to share selfies of your runs in the Running is fun??? Who knew?! thread, but you can also just do it.

HOW TO PARTICIPATE: Our goal is to raise as much money as we can for ARC Southeast. We suggest a minimum donation of $10. Please donate online, directly to ARC Southeast, any time before August 26. Donate at this link: https://arc-southeast.org/donate/. Then, submit a screenshot of your donation to this form, so that we can tally the amount raised: https://bit.ly/clubpicklefunrun

WHO CAN PARTICIPATE: Anyone! Invite your neighbors, tell your families. You don’t have to run to participate — walking is welcome — and you don’t have to be a subscriber or follower of Culture Study, either. Donations are welcome from everyone, runners and non-runners alike!

If you have more questions, you can leave them in the comments below, or hop on Discord and ask away. I’ll put another reminder in the newsletter in the weeks to come, but if you want to participate, put it on your calendar.

Just an overarching reminder here that I should have put up top: please avoid equating weight or body size with health and no weight numbers please!

School left me with the belief that fitness and sport was the same thing. And definitely for other people as I had no natural athleticism or co-ordination. I was always picked last for teams. Along with coming from an immigrant culture who had no concept of walking for leisure, in my adulthood I barely moved. I fell into running via taking up canicrossing for the sake of bonding with my dog in my early thirties. I tried a couple of runs by myself in a vague belief I should be doing exercise. Did not get very far - a few hundred meters and I was puffed out. My belief that fitness was for other people was so ingrained that I would not wear running gear as that's for 'real' fitness people. Until a jog leader gently told me cotton t-shirts were not a good idea in cold rain. I discovered running in a group is completely different from running by yourself - which is counter intuitive given it's the same simple motion. Something about going slower in a group, pacing better, having others to keep you going. Through the kindness of others I was introduced to trail running. Due to my immigrant background, this was almost literally a whole new world opening up. I tagged along, the runs got longer, I got more trainers. One day I was part of a relay team doing an ultradistance route and ran alongside ultrarunners. I realised they weren't skinny muscular folk. They were normal. They were walking. Intrigued I signed up next year to do the race as an ultrarunner. And it's wonderful. The races in Scotland are often run by informal organisations with one or two folk and whole lot of volunteer marshals, so it's a real informal, welcoming community (there are ultra races run by event companies - it's a different vibe I feel). You don't have to be 'athletic' you just need to keep on going. I can so do that! Due to the pace you meet allsorts on the route and even a shy person like me can chat to people. Due to the risk of injuries as the longer you go, I signed up for a gym. Something I could never imagine doing in the past. I discovered a love of strength training. I have better eating and sleeping habits now to help with recovery and training. I feel so much more comfortable with my body and who I am. I wonder how many people miss out on this due to being scarred by school?