Do you read this newsletter every week? Do you value the labor that goes into it? Have you become a paid subscriber? Think about it! Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are people who haven’t gone over to paid — and I get it, I really do, I’m constantly saying I’m going to pay for things and take weeks to actually do it. But maybe today is your day.

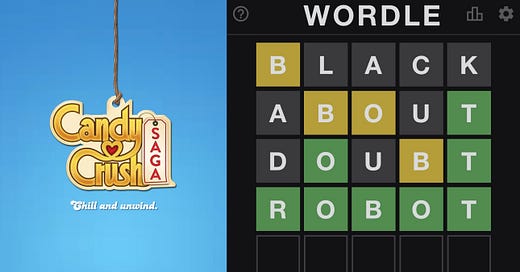

Right before Christmas, I had some extensive dental work that refused, for a lack of a better word, to settle. Earlier in the week, I’d gotten the 1-2 punch of the flu shot and my Covid booster. And I found myself doing something I hadn’t done in years: I downloaded Candy Crush.

Candy Crush — and its dozens of “sister” games, which are really just Candy Crush with different shaped items — is a slot machine dressed up as a phone game. You move candies around to match, and then they explode. You can be “good” at Candy Crush but it largely a game of chance. Its addictive properties are well-documented and, depending on whether or not you’re reading a piece of gaming-press, celebrated.

There’s no real end point to Candy Crush (right now, there are over 10,000 levels, with more added all the time). Each level is just different and just challenging enough to keep you trying to defeat it. I don’t have proof, but I feel very strongly that if you’ve been working on a level for a long time, run out of lives, and come back to the game a day later, the game eases the difficulty so that you get a win that propels you to keep playing.

I refuse to spend money to gain more lives when my five run out (it takes 30 minutes for a new life to refresh) but the temptation is real. (King, which makes Candy Crush, its offspring, and pretty much nothing else, brought in $652 million just in the third quarter of 2021; earlier this week, Microsoft acquired King and parent company Activision Blizzard for $69 billion).

Candy Crush is satisfying the way 94% Fat Free microwave popcorn is satisfying: you can’t stop eating it once you start but you never feel good and satiated afterwards. At this point, I know that the game’s (re)appearance in my life is usually a good sign that I’m feeling burnt out. In this case, I downloaded it in a haze of physical and mental exhaustion. But it’s stuck with me for a month, superseding my reading and all the other things I actually want to do. I play it every night and I hate it so much.

Since the last time I downloaded the dumb game, it’s leaned into its placement in exhaustion culture: small banners on the launch page invites users to think of playing as an opportunity to “chill and unwind” or “swipe the stress away.” I kinda can’t believe this, but the current version of the game is branded “MINDFUL JOURNEY SEASON.”

The idea here, I think, is that Candy Crush is meditative because it empties and focuses the mind. But that’s a very bright spin on the particular numbness that Candy Crush creates. I am a very novice meditator, but I know that what my brain does during meditation is very, very different than what my brain does during Candy Crush. One makes me feel like the world has come into soft focus. The other makes me feel nothing at all.

There is no past or future in Candy Crush — just micro-wins that ultimately feel flat and meaningless. Again: it doesn’t alleviate the feeling of burnout; it matches its temperature, like one of those sensory deprivation float pools. It’s ostensibly soothing but, in truth, a sort of brightly colored succubus: an app you didn’t know was open on you computer, running in the background, draining all the battery.

Games like Candy Crush suck our leisure time — our snatches of empty mental space, our interstitials — but unlike actual hobbies or leisure or boredom, give us nothing in return. Boredom, after all, can make the mind come alive, similar to seemingly “mindless” activities (weeding, walking, knitting, woodworking, baking) that allow the mind to exhale. Candy Crush is like a sharp inhale, over and over. It’s not stressful, per se, but nor is it restful.

I don’t think this is true of all video games by any means. But it is true, I think, of this game. (I also think Candy Crush, with its slot machine pyrotechnics and monetizing pushes, functions differently than Tetris, which has been shown to help with PTSD).

Something happened a few days after I downloaded the app that drew these qualities into focus. My days filled with two holiday traditions: 1) the New York Times “mega” crossword (which takes up to full newspaper pages and comes out around the second week of December every year) and 2) an intricate 1000-piece puzzle.

Both are consuming and diverting in a very different way than Candy Crush. First off, they’re “open” systems: you can, ideally, collaborate with others. Not everyone does the crossword with others’ feedback, but in our family, we sure do, particularly with the Mega. And puzzles are nothing if not invitations: anyone can come sit down and give it a try. When I was growing up, my Grandma and Great Aunt would come from Minnesota to visit us in Idaho for several weeks at a time. There wasn’t always a lot to do. But there was always a puzzle that they could work at and my brother and I could join. I don’t remember what we talked about. But it was presence, it was intimacy, it was quality time.

My friend/Culture Study community member Tina has a theory that puzzles are the very best way to start conversation or integrate new people into a group of friends or pretty much make any social situation feel more comfortable. You have a task at hand, but the task is not pressing; you’re not looking each other in the eye, so the pressure on the conversation and interaction is significantly decreased. You’re just chatting and puzzling, puzzling and chatting. Maybe someone is “good” at puzzling but it’s pretty hard to actual manufacture puzzle competitiveness.

Puzzling is the sort actual “chill and relax” that the Candy Crush screen promises. It’s not totally mindless — there is a goal, and there will be catharsis! — but it’s also not brazenly manipulating your attention so as to persuade you to make micro-transactions. Puzzles do cost money, but the principle of the puzzle operates outside of capitalist imperatives: sure, you can’t keep doing the same puzzle forever, but multiple people can do the puzzle over time. You can check puzzles out from the library, or join the Culture Study Discord and hang out in #puzzle-swap. The principle remains: after the point of purchase, a puzzle’s purpose as puzzle is not to continue to generate money.

Which brings me Wordle. In a way, it spread similarly to Candy Crush, whose creators understood that by inviting users to “reup” lives by connecting the game to Facebook and asking friends for lives, that they were essentially introducing the game to entire networks of people. Wordle was created by software engineer Josh Wardle (lol) as a gift to his partner, who had become enthralled by the New York Times crossword and the (relatively new) game Spelling Bee.

If you grew up in a word-play family, you might recognize Wordle as a slightly-tweaked versions of Jotto. You guess a five-letter word, then the game tells you whether you have the right letter in the right place (green) or the right letter in the wrong place (yellow). You can read a much better description of the game in this interview with Wardle, but the most important attributes are that 1) it’s not engineered to make money (indeed, it’s not even on an app); and 2) you can only play once a day, but everyone gets the same word.

That everyone plays the same word allows the game to become social — particularly after a New Zealand user figured out how to add a “share” widget that anonymized individual players’ attempts in the form of square emojis. That stock of blocks up there will be meaningless to you if you haven’t played the game; if you have, you’re probably like “what in the world was she doing on Try 3” (listen, it was my first time playing).

My Mom and I have been sharing our Wordles back and forth every morning. She shares them with her good friend who first got her hooked earlier this month. Four of my best friends and I have a group chat where we share. Earlier this week I woke up to this tweet, from friend-of-the-newsletter Meg Conley, and felt giddy to give that day’s a try.

This is admittedly nerdy shit! But it also makes me feel so much less dead inside than Candy Crush!

Over at Vox, Dr. Katy Pearce makes the case to Aja Romano that part of Wordle’s appeal is this sort of low-stakes, low-lift sociability — particularly appealing in a time when so many of us are both craving interaction but too wiped to actually take the steps to make it happen. “More intensive social experiences are harder to come by right now,” Pearce told Romano. “People just lack [the] bandwidth to interact.”

That seems right to me, but I also think Wordle’s appeal stems from its contrast with the areas of our lives where we find our ourselves assailed by imperatives for growth and profit. On social media, every post is shadowed with its quantifiable reception (how many likes, how many retweets?). When you read an article online, it’s surrounded by ads trying their very best to get you to accidentally click away. Every other Instagram post is a ghost of my previous browsing history, attempting to beguile me. But Wordle refuses those imperatives, much to the dismay of many in the tech community.

This is ultimately a story about control. Burnout, particularly when interwoven with depression, makes it difficult to actually choose to do the things that you really do want to do — socializing, getting outside, reading the book on your bedside table, not canceling an appointment, showing up for someone, fixing something, just doing something that you choose. You often find yourself on the path of least resistance, whether that means binging a television show you don’t even really like or scrolling Instagram until you get a recharged life on Candy Crush. You revenge bedtime procrastinate. You feel passive in the flow of your own damn life — and frustrated that you can’t muster the strength to redirect it.

A game like Candy Crush exploits burnout. Wordle, much like a puzzle or crossword, offers a moment of restoration. The mind is active but calm; I choose to start it, and then it ends. And as a result, it feels much easier to choose the things I actually, truly, want to do, instead of ceding my time to a row of four exploding candy icons.

I don’t blame anyone who’s found themselves in that swirling eddy of exhaustion, and I don’t blame myself. So many of our online experiences are engineered to keep us in that passive position. But I also know that letting Candy Crush hang out on my phone keeps me from the parts of myself, and my brain, that I like the most — and makes it more difficult to make the decisions that feel like me. Whatever your personal Candy Crush is, deleting, blocking it, or throwing it in the trash will certainly help limit its power. But the bigger thing, at least for me, is acknowledging that power in the first place. As in: actually and truly saying “this is what this thing does to me.”

Candy Crush wants you to think that it’s “just a game,” just like Instagram wants you to think that you’re just quickly checking in on pictures of friends. Naming the rot somehow makes it easier to reject it — or, at the very least, recognize its inverse when you see it. For me, that was the puzzle. For you, it might be Wordle, or an actual book, or spending hours on a recipe, or meditating, or singing, or gardening, or really playing with a child, or staring at the sky until you feel small and wondrous.

Whatever it is, I hope it feels like you chose it — really and actually chose it. And I hope, above all else, that it gives you the rest of which you are so very, very worthy.

To access the Weekly Things I’ve Read and Loved, subscribe here:

Subscribing is how you’ll be able to participate in the heart of the Culture Study Community: in the weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece (and a whole thread dedicated to Word games), plus equally excellent threads for discussion of Job Searching, Puzzle Swap, Romances Are Good Actually, Bodies Are a Horror, DC Where the Metro is On Fire Again, The World Language Department, Brooklyn & Bailey Hive, Spinsters, Fat Space, Non-Toxic Childfree, Doing the Work of Building Community, WTF is Crypto, So Your Parents Are Aging, Diet Culture Discourse, and a lot more.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. Finally, you’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I've been hunting for a way to explain how I feeling and I'm so relieved to read it this morning..."You feel passive in the flow of your own damn life — and frustrated that you can’t muster the strength to redirect it." This world is pretty hostile to folks who need rest before figuring out what their next steps are, and rather demands that in the depths of exhaustion or depression they also take the steps needed to ameliorate their exhaustion or depression. I feel trapped by my own inertia.

I don't have anything specific to say other than to state how much I enjoyed reading this and how thoughtful and insightful it was.