If you read this newsletter every week, value the labor that goes into it, and haven’t become a paid subscriber — think about it! Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are people who haven’t paid — and I get it, I really do, I’m constantly saying I’m going to pay for things and take weeks to actually do it. But maybe today is your day.

Just going to start this newsletter with the admission that I’m tired — releasing a book requires a lot of labor, some visible and some not, and yesterday I had one of those days where about 1 pm I was like “why do I feel like I have been scraped from the underside of a garbage truck, even though I got over 8 hours of sleep last night?” The answer, of course, is accumulated stress and work, and trust me when I say that I have a plan to recover from this intense period of work soon. I’m also so grateful that Past Annie had the insight to put together questions several months ago and send them to one of the smartest thinkers I interviewed for the book, Sara Jensen Carr, Assistant Professor of Architecture, Urbanism, and Landscape at Northeastern University, and have them ready to publish today.

Out of Office is, as I put it on Instagram earlier this week, a curious hybrid: like an airport business book went to history grad school and then figured out it wanted to be a sociologist. A full fourth of the book is devoted to thinking about community, and part of that research necessitated talking to people who’ve spent much longer than we have thinking through these larger topics about how upheaval (in work, in pandemic) influences the spaces where community resides.

I’ll let Sara’s answers here speak for themselves, but I hope you’ll also check out her wonderful, beautiful, and challenging book — The Topography of Wellness: How Health and Disease Shaped American Landscape. I know so many of you deeply appreciate encountering ideas that make you think about things you’ve never thought about before. Her work will do that — and a lot more.

I want to start by talking about the word “wellness.” What does it mean to you — particularly when it comes to public health and public landscape? You talk about this a bit in the book, but I’d love to hear more about the debate over its use versus, say, “well-being.”

I feel like it’s such an academic tic to define your terms of your dissertation, but when I proposed the title to the publisher, one of the first comments that came back was that I had to clarify what I meant by “wellness,” and it actually was a really helpful exercise in outlining the themes of the book. In trying to source definitions for well-being vs. wellness, there was actually an article in (wait for it) the International Journal of Wellbeing specifically discussing the lack of theoretical underpinnings for the term. That said, in terms of health measurement and policy, “well-being” tends to encompass not just physical health, but self-satisfaction, purpose in life, and most importantly to me, autonomy and a feeling of control over one’s circumstances. “Well-being” is also a metric that is often used in health indices, again, taking into account mental health and resources.

“Wellness” has been less defined, especially in the public health sphere, and what it infers is more problematic, and as a result more interesting to write about. I think we often use “wellness” as a stand-in for “health,” but just as the WHO stated in 1978, health is not merely the absence of disease, even though that’s often how many still conceive of it. “Wellness,” especially in the United States, indicates the total eradication of illness but also invokes a more image-conscious version of health, one that can be packaged and sold, rather than ensuring more widespread, long-term health equity through institutions and environments.

In that sense, the mutation of that term became appropriate to how it has been used to describe public landscapes and drive design in the American landscape. That ranges from well-meaning and even successful movements like the post-cholera and yellow fever impetus to build underground sanitary infrastructure and advocate for daylight access and fresh air ventilation in working-class housing to much more insidious ways “wellness” has been weaponized, such as using the poorer health outcomes of Black and immigrant communities as justification to eradicate their “unhealthy” neighborhoods through urban renewal and highway building and excluding them from white suburban enclaves citing their “lower mortality rates,” even though those inequities in health were ensured through poorer health care access and racist policies.

Then there are public landscapes where intents and outcomes are much more ambiguous. Frederick Law Olmsted’s design of Central Park was intended to be a democratic landscape that would be accessible to all citizens, and he wrote passionately about the health benefits of nature, especially for those that weren’t privileged enough to escape to the country or resorts outside the city.

That said, there is also a strain of Progressive Era-style paternalism in his writing as well, in that the mixing of economic strata would have a “civilizing” effect on the working-class, and although Olmsted wasn’t involved in the land acquisition of Central Park, he did refer to the site pre-improvement as a slum, when in reality it was built on the the grounds of Seneca Village, a thriving African-American district whose residents were removed to build it, as well as an Irish settlement.

I think we can also see this in a lot of contemporary strategies to try and improve environments for health - namely re-shaping urban design around increasing walkability or new high-end parks like the High Line or Atlanta Beltline are ostensibly good but can catalyze gentrification, making neighborhoods unaffordable for the majority of people, although maybe that also speaks to the general paucity of quality open space in our cities and towns.

I am obsessed with playground design and loved the section of the book on “the playground movement” and the way it conceptualized of the child “lost” to urban living. Can you tell us more about what the playground movement was trying to address, and how we see its manifestations today?

The playground movement was born out of the larger child-saving movement, which also just predates child labor laws of the 1930s. The movement was mostly led by upper-class women but also reformers such as Jane Addams and Jacob Riis. They were concerned not only for the detrimental effects of the city to children’s moral character, but also how industrialization would rob them of their essential nature, so that they needed to provide spaces and even instruction for play. Again, there’s more than a twinge of paternalism in the movement and how it was carried out, but the idea that we have a societal responsibility to provide for and even prioritize and celebrate child development is so compelling to me, especially as a parent, but I also think it’s something that’s been lost when we talk about the shaping of towns and cities.

There is lots of literature about the child-saving movement and playground history; one of my favorite books that I referenced for that chapter and really expands on these ideas about child development and design is Alexandra Lange’s The Design of Childhood. And while I am not one of those scholars, I can say what I see as a landscape architect and a parent. The first thing that comes to mind is that risk has essentially been engineered out of a lot of these environments. I have a friend who is in practice who told me about a project her firm had at a fancy private school in San Francisco. The parent organization wanted as many safety features for the playground as possible, especially really soft ground surfaces, but the principal, who was a child development expert, said that without some element of risk in the design, children never learn to navigate their own boundaries and safety.

Beyond this trend in playground design, though — like everything else about our fragile institutions the pandemic cracked apart — I think the lack of physical and social infrastructure for children would be at the top of that list. Not only the failure to prioritize safe schools for children, teachers, and staff, but how long playgrounds and parks stayed closed in some places like California, long after evidence showed that COVID was not spread through surface contact and had very little transmission outside. And that’s just in neighborhoods that actually have accessible playgrounds to go to in the first place, obviously there are lots of places where kids had nowhere to go for months on end. Just like school and childcare, the built environment is another arena where parents have just been left to figure out how to navigate on their own.

The book includes an amazing chapter on perceived “cancer” of urban blight and urban renewal that immediately brings to mind a lot of the rhetoric around encampments for the unhoused and the “hostile” architecture intended to deflect it. Can you connect some dots for me (or unconnect some dots) about how these discourses do or do not echo each other, and the stakes of a different sort of wave of post-Covid urban renewal?

I lived in New Orleans for nine years, the last two years which were post-Katrina and I was mostly doing recovery-related projects at the architecture firm where I was working at the time. So I was witness to a lot of debates about how to build more “sustainably,” which can be a cousin to building for “health” I think. One of the early recovery plans that came out just showed large green circles, meant to represent parks, in the lowest-lying areas of the city, which of course had a significant correlation with the poorer neighborhoods.

You don’t want people to live in environmentally vulnerable neighborhoods, but it’s also using this lever of ostensibly unimpeachable values like sustainability or health to displace and remove without thinking about the necessary protection of larger social systems or safety nets, and at its worst becomes more about protecting the good health of the privileged lest it spread to those neighborhoods. That was used as a justification for urban renewal by hitching it to the fears people had of cancer at the time, which was just emerging as the leading cause of mortality in the U.S. I remember when I was in grad school reading about how Occupy Wall Street settlements were cleared out by citing public health concerns.

I’m not sure if we’ll see widespread COVID-related clearing out of neighborhoods; I think more so we’ve seen the benign to malignant neglect of hotspot areas when it comes to their environmental conditions, without a lot of recognizance that those hotspots also had a lot of predisposing conditions for COVID severity like air pollution, lack of public space, and substandard housing due to histories of environmental injustice. There are also certainly other smaller scale troubling patterns that have already come out of the pandemic like increased policing of parks and public space.

I should also maybe contextualize this by saying that I started my career in architecture, designing and doing construction management primarily for healthcare facilities. There is so much rich research in that particular niche regarding the relationship between the design of the environment, care, and health outcomes. My experience post-Katrina is ultimately what led me to go back to grad school for a Master’s in Landscape Architecture and then my Ph.D. in Environmental Planning — to understand how some of those same concepts could be applied at the scale of public space and infrastructure, only to find it’s much, much more complicated but also such a vital need. At my heart, I’m still a designer myself: I believe in the power of design to heal as well as harm, but as a profession we need to be recognizant of this history where the justification of “health” has been used for more nefarious ends.

You and I talked almost a year ago, when you were receiving a ton of interest in your research because reporters wanted to talk to someone about how Covid was going to change anything and everything. At that point, your book had been finished for some time, but a year into doing those interviews, and just generally thinking about Covid’s effects on landscape and public space and architecture, what are you seeing? If you were to write another chapter today (sorry, I promise you don’t have to do this) what would it focus on?

Here’s a funny story: I had been working on this book, which is all about how epidemics have influenced landscape and urban design on and off for about six years, through two tenure-track jobs, three cross-ocean/cross-country moves, and having three kids. I turned in the final draft of the manuscript in...February 2020.

I was ultimately able to rewrite the introduction and conclusion to at least address COVID, but for most the year I was locked down with a 6-year-old and 2-year-old twins while trying to navigate switching to online teaching, the continued pressure of being on the tenure track, and just the generalized terror of the pandemic. Although the book wasn’t out yet, there was a description of it on the Graham Foundation website, and I think that’s how a few journalists initially found out about my research, and then it just snowballed from there. I tried to be as honest as possible when people would ask me to predict what I thought the effects of COVID would be on the built environment, and I would respond that we’re still very much in it, so I don’t know!

The epidemics I wrote about lasted decades, and it takes another several years to see responses manifest in the built environment given the timelines of design and construction. On my most pessimistic days, I think nothing will change. The mitigation strategy has been understandably so dependent on the vaccine that I don’t know if we’ll see the scale of environmental change we did in the past.

Given the politicization of individual choices such as masking and vaccines, I think environmental interventions and informed design are actually much more urgent than many people think they are. A lot of the ad hoc changes we’ve seen — streeteries, distancing stickers in stores, or plexiglass dividers — aren’t really about protecting public health on a larger scale, nor are they that effective. At some point, though, we will have to reckon with underutilized office space and retail, changes in modes and patterns of commuting, which has already shaped so much of the American landscape. In the best case scenario, now that we now know it’s an airborne disease, I wish we would be more proactive about ensuring fresh air ventilation in buildings, especially in schools and low-income housing, as well as addressing green space equity. These would have so many other health benefits besides pandemic resilience as well.

In the short term, I’m interested in revisiting how the narrative of COVID transmission changed over time and how that affected perceptions of public space. In the book you can see an arc of how architecture, landscape, and urban planning have responded to how they thought predominant illnesses of the time spread, and how certain perceptions persisted even when evidence emerged to the contrary.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was the fear of miasma — or that disease spread through the air, and in turn the elimination of “bad waters” thought to emit those gases. In the mid-century, it was germs and appropriating the language of contagion to try and understand the dynamics of the built environment. More recently, there has been a lot of interest in shaping behavior, i.e., walking and biking through design, originating with fears of the obesity epidemic. The pandemic has been like watching over 100 years of public health history compressed in a couple years — we all remember the intense fears of germs in the early days, we changed our behavior to socially distance and quarantine, and now that we now it is an airborne disease hopefully we see changes to that effect, which is why I think the chapters dealing with the effects of miasmic thinking and early respiratory diseases like tuberculosis and the Spanish Flu are so relevant.

Because a significant chunk of your book deals with the 19th and early 20th century, you also get to use a bunch of imagery that is now in the public domain (or otherwise affordable to license). The book is also in a wider format than a traditional (humanities or social sciences) book, which I know is more typical for architecture/design books, but feels like a luscious treat given the formats in which I’m usually reading. And yet I also wondered about all that you couldn’t include — are there any images that you’d like to talk about here? And/or, what was your favorite archival or research discovery while writing the book, and what larger concept did it help open?

I appreciate you noticing that! My brain is completely fried after the past couple years but I really feel like I have to write another book if only to capitalize on everything I learned in the process of writing this one. You have to obtain and pay for image rights, that you need to hire an indexer, you often need to pay your own subvention for printing costs, especially if you have a lot of images like I did, and you have no control over the cover.

Luckily, I won grants from the Graham Foundation and J.M. Kaplan Fund that covered the image rights and some production costs, although I still had to be judicious in how they were used. I’m a designer myself and a visual thinker. When I put together a lecture or even a piece of writing, I start with finding images and shuffling the order to find the narrative. So it was a really fraught process to find the right images for the book and also editing down the final selection. That said, it was also important to me that the images that ultimately ended up having enough space to breathe and would be big enough for the reader to examine for themselves, given the amount of architectural plans, maps, and diagrams that are in there.

My mentor in graduate school was Louise Mozingo, who wrote the excellent and visually lovely book Pastoral Capitalism, which is about mid-century suburban office parks, and I shamelessly just gave it to University of Virginia Press as an example and said I wanted it to be the same dimensions. To their credit, they agreed and made it happen!

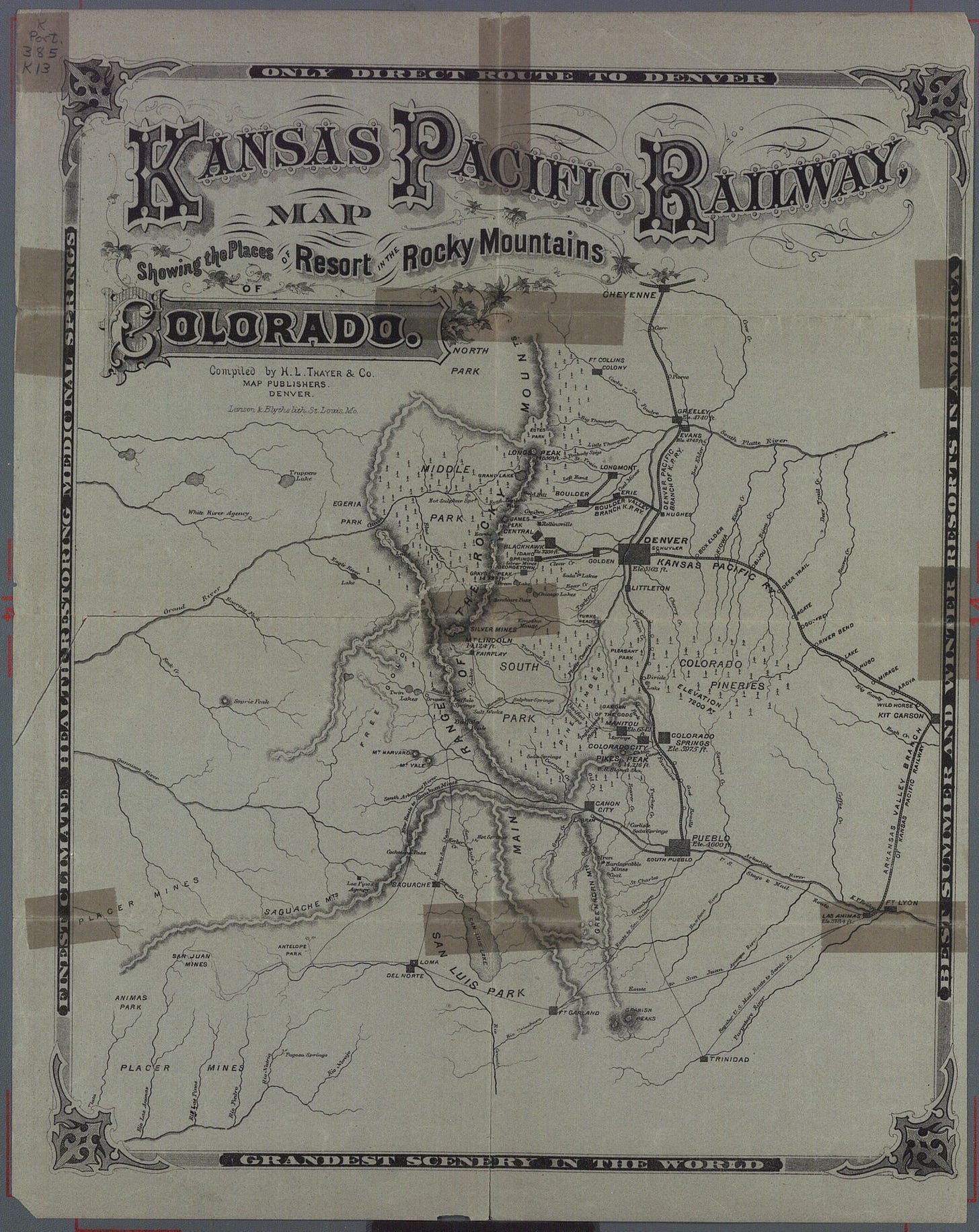

There was a great railroad map I had from the Kansas Pacific Railway that showed its westward expansion specifically to the “Health and Pleasure Resorts” of the Rocky Mountains. I loved it because it says so much about how much the American landscape has been shaped by the pursuit of wellness, the commodification of healthy landscapes, and the escape from “sick cities.”

Unfortunately, it had to be cut — not because of image rights issues, but because given its size and level of detail it wasn’t going to reproduce well in the book. To continue on the topic of urban renewal above, the manuals and maps many cities produced to document blight and justify the destruction of mostly Black neighborhoods also speak volumes about how the fear of an illness with unknown vectors, like cancer was at the time, could be invoked to try and rationalize or add a sheen of objectivity to such destructive policies in the name of eradicating disease, or really the fear of the “contagion” of urban afflictions, moral or otherwise, spreading to the white suburbs. Again, it just wasn’t going to reproduce well in the format of the book but of course many of these are government documents in the public domain, so if anyone out there is interested in the topic, they are really illuminating to read.

What’s a public space (or 2!) you’re fascinated by right now?

This is a completely boring answer because he gets a ton of attention in the book — and I’m a landscape architect working in Boston — but Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace, which is an entire system of parks that runs for over seven miles and is over 1,100 acres, is just a masterpiece of public space and ecological resilience. He had so much foresight into how it would work as a commons but also be a place where people could breathe fresh air and escape from the activity of the city, but also mitigate stormwater flooding and urban heat. I work right at its edge and I bring students there all the time because the lessons it offers are truly timeless, and it’s a living, growing system, especially as its immediate contexts change.

I also work in and outside of the classroom with the Emerald Necklace Conservancy, the nonprofit that stewards the system and brings attention to the need for more accessible green space in Boston, and think it’s important to show students why that type of advocacy is needed now more than ever, but also how complicated and fraught a process it can be.

And while it’s not a specific public space, I’m super interested in what could happen with streets and parking lots post-COVID. They take up an inordinate amount of space in our landscape already, and with the commuting changes post-COVID, I think that will become even more apparent. I think there is so much potential if we can figure out how to de-toxify and remediate that infrastructure to create healthier places, actual public spaces, and a more equitable distribution of green space. It seems really vulture-ish to say a tragedy like the pandemic presents an opportunity, but with any luck, it will at least become a catalyst for change in how we view the relationship between our environments and our bodies.

You can follow Sara Jensen Carr on Twitter here — and buy The Topography of Wellness here.

Thank you for reading! Paid subscribers get the weekly recs on their Sunday newsletters, the ability to comment on posts, plus access to the heart of the Culture Study community: the weekly threads and the Discord, where we talk about the most recent newsletter and so much else (Job Searching, You Used to Be a Christian, Brooklyn & Bailey Hive, Spinsters, Fat Space, K-Pop, Non-Toxic Childfree, Doing the Work of Building Community, WTF is Crypto, GBBO, So Your Parents Are Aging, HIGH PEOPLE ONLY, and a lot more). If you haven’t joined yet, send me an email and I’ll help you out. If you’re intimidated by Discord, don’t be. It’s a delight.

I’m also working with Curio to have all newsletters available in audio form — and they’re free for subscribers. Here’s the RSS feed, and here’s how to plug an RSS feed into your podcast app.

You can find a shareable version of this piece online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I find it so fascinating (and depressing) how often the "ob*sity epidemic" is referenced right alongside cholera outbreaks and Spanish flu and covid, as though fatness is contagious or something you need to quarantine against. I don't mean to say Sarah believes this! I understand that she's referencing it in terms of actions that have been taken by urban planners in response to a perceived threat. But it's something I've been thinking about and I would love to read a dissection of that really common framing from someone more knowledgeable than me.

Anne, thank you soooo much for this interview! Sara Jensen Carr, I can't wait to read your book, because it seems like it covers all of my urban planning interests - encampments and ending homelessness, planning for children, street and parking lot diets!

I work as a town planner and it blows my mind that I cannot convince the county school system (as part of an elementary school reconstruction) to install a missing piece of sidewalk at a traffic light crossing for children walking to school from the neighborhood across the street. "They can just take the bus" is their answer - never mind the autonomy and independence it gives kids when they can walk safely! Not to mention that this also gives these kids better access to the playground and playing fields after hours.

As a planner, I legit worry that one day I will be seen as a negligent parent because I want to give my child a sense of independence that used to be normal. For instance, the only day of the year that my mom would accompany me to the bus stop in elementary school was the first day of school - now I see middle school parents walking to and waiting at the bus stop with their kids on a daily basis! And we wonder why there is a rise of anxiety among kids and teens - we don't trust them to do something as simple as walk to the bus stop by themselves until age 14, whereas I was taught how to drive a truck around my grandparents' farm at age 11! It blows my mind because in so many ways the world is safer today (if there's an emergency, everyone has a cell phone!) yet we restrict kids more than before.

I wrote my graduate capstone project on compassionate planning for unsheltered homelessness back in 2017, and I directly countered the common "public health" complaint by - gasp - suggesting that the city provide basic services like trash pick-up and port-a-potties! While it's not ideal for people to be living long-term in encampments, why not at least try to mitigate the public health issues in the short term while increasing permanent affordable housing in the long-term!

As for parking, it's mind-blowing how much money goes into building and maintaining parking, especially in a mixed-use development with a parking garage. My town has been trying to attract developers into building mixed-use residential downtown and the projects keep stalling because of the cost. I would love to reduce (or ideally eliminate) the parking requirements and encourage landlords to include discounted monthly passes to the municipal garage in the cost of rent. My town is 25 miles outside of a major city with very barebones public transit, so we have to be realistic in that even if families are working from home, they may still need two cars for the rest of the week.

I do love how many restaurants have set up large tents in their parking lots and how there's still parking leftover; I hope outdoor dining becomes a more permanent thing.