The Wages of Overwork

Or: What Happens When the Ruling Class Gets Bad at Pretty Much Everything Save Work

Do you value the work that makes this happen twice a week, every week…that introduces you to new authors and books and just generally thinking more about the culture that surrounds you?

Consider becoming a subscribing member. Your support makes this work possible and sustainable.

Plus, you’d get access to this week’s really great threads — like Tuesday’s on regional food delights (I could honestly read these forever, also please serve me a Trash Plate) and Friday’s thread dedicated to asking/receiving advice on how to provide for care in specific situations.

As part of your job, do you receive or send emails outside of “normal working hours"? What about texts or phone calls? Is there an unspoken but spoken expectation that you’ll keep on top of your inbox before coming into/officially logging on to work, or that you’ll check your Slack or Teams messages before you go to bed? That you’ll answer student or parent queries? Can you even remember a time when this wasn’t the case?

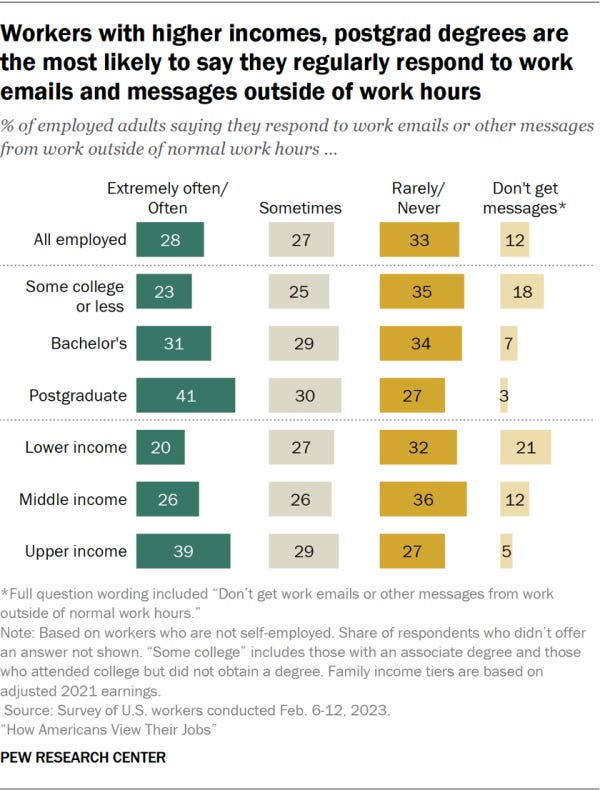

In February 2023, Pew asked nearly 6000 nationally representative workers how often they respond to work emails or other messages from work outside of normal work hours.

41% of workers with a post-graduate degree answered extremely often/often — compared to 23% of workers who’d completed some college or less. 39% of upper-income workers also responded to work emails or messages extremely often/often — compared to 20% of lower income workers.

The data isn’t surprising. But it underlines something that we’ve been talking about for some time now. The more educated you are, the more money you make — the more time you spend working, and the slipperier your work becomes, oozing into all corners of your life. The more you’re paid, the more ostensibly prestigious your job, the more time you spend working outside of standard working hours. (Conversely, the less money you make, the more likely you are to have not enough work: the same Pew study found that 23% of lower income workers report that they have too few working hours, compared to 4% of upper income workers).

This is a marked switch from, say, the 19th century, when the rich worked as little as possible and the poor worked as much as possible. It’s not that the rich became industrious and the poor became lazy; it’s that the poor organized to gain a living wage and protect themselves from exploitation, and the rich, or at least the “new” rich, used their own “industriousness” (e.g., working all the time) to frame them as both morally upright and outside the critique of the entitled leisure class.

But part of it, too, was structural — a direct result of the “billing hour” as the be-all-end-all of professional advancement in a small but influential corner of American industry. These jobs are ostensibly salaried, but a worker’s salary is bolstered (either through bonuses or advancement) by the sheer number of hours billed. And billed hours don’t have to be creative hours, or efficient hours, or collaborative hours. They just have to be.

The high-income high-status jobs that demand the most hours are known, in sociological terms, as “greedy” jobs. Think finance, of course, but also big law and consulting. Back in 2019, Claire Cain Miller busted my mind wide open with a piece on how the standards of these greedy professions have effectively negated women’s educational gains (and calcified the inequitable distribution of domestic labor) in homes where both partners have the same educational level. (Go read the article for more, including the hall of fame quote from economist Claudia Golden that “Women don’t step back from work because they have rich husbands. They have rich husbands because they step back from work.”)

You could easily argue: these people are making millions of dollars, who cares if they’re reifying gender norms and grinding themselves into dust! So they’re work robots and miserable — maybe they should be. If they want to work that many hours a week in order to make that much money — let them. I mean, isn’t that the heart of the “right to work” movement? If someone wants to exploit themselves, that’s liberty in action!

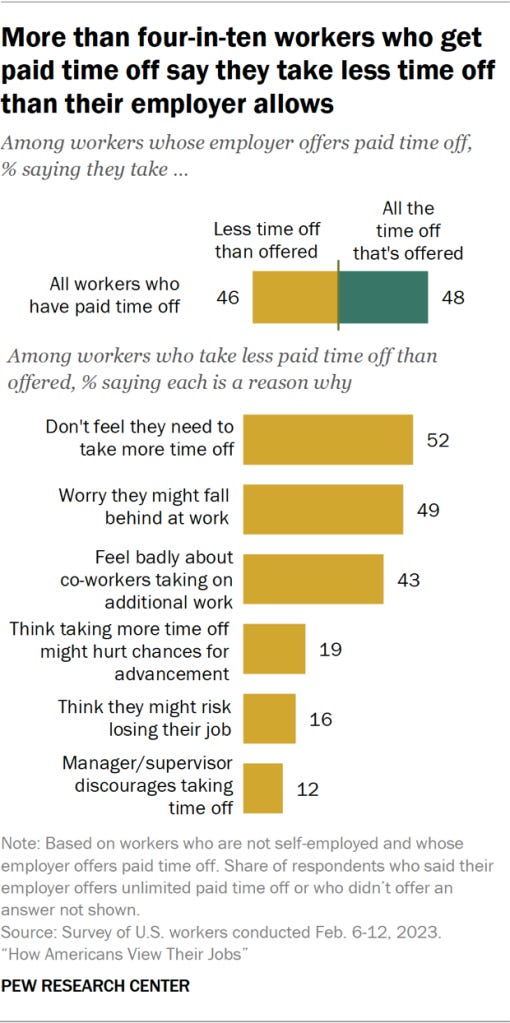

But the norms of the rich and powerful influence the norms of those striving to be rich and powerful. Work culture at the highest echelons, in the most handsomely-paid professions, trickles down to professions where work is far more precarious. Today, people with paid time off (which, generally, are also people who are not lower income) work more hours and, when they have paid time off, don’t take the full amount. Not because they love their work, but because that’s the standard — and they’ve rationalized that they don’t need it.

Look at that graph again: 46% of workers don’t take the full number of paid days off offered by their employer, and of that 46%, more than half of them don’t do it because they didn’t feel like they needed it.

Who doesn’t “need” paid time off? People who’ve convinced themselves that more work is better! Also of note: the 49% of workers who know that taking time off will simply result in more work in the margins to catch up, or the 19% who think it could hurt their chances of advancement, and the 16% who think they might lose their job.

Working more days than you and your employer have agreed is the appropriate number as a salaried employee? Overwork culture. Normalizing communication outside of standard working hours — while keeping the understanding that you should also be available and communicative during standard working hours? Overwork culture. Adhering to these norms because they’re your best insurance against precarity? Overwork culture.

None of this is new, not exactly. You could readily substitute “burnout” for “overwork” in the paragraph above and the meaning wouldn’t change. What I’m thinking about, then, is the effects of overwork culture on those who are forced to adopt its norms without any of the premiums — in pay, in the option for paid time off, or in benefits. As much as we talk about how people have the right to “do what’s right for me and my career,” we have to acknowledge: the wages of overwork culture extend far beyond the working conditions of those who embrace it.

Earlier this month, the New York Times Magazine ran its annual “Work” issue. At its heart: a piece by cultural historian Fred Turner, outlining how the labor movement fought tirelessly for the division between work and leisure — one that the movement towards so-called “flexible work” are eroding. The piece hinges on the ways that new tracking technologies (especially to do with rideshare, delivery, and warehouse work, but also screen monitoring) have been instrumental in the overall erosion of worker control over their time.

The article largely focuses on the dystopic future for hourly workers — which is important, because those workers are most acutely and immediately affected by these changes. But you know who doesn’t really show up in Turner’s argument? Salaried overworkers — a constituency that has rarely fought for a division between home and work, because violating that division has become a primary tool for advancement. They might not love overwork, but they’re also not interested in protecting themselves against it. Who are they, what is their value within the system, if not their ability to overwork?

Back in the early days of the newsletter, I wrote about why the salaried office worker has historically resisted unionizing. Once people moved out of the working class into what was historically called “white-collar” work, their guiding impulse was to 1) differentiate themselves from blue-collar workers and 2) move up the organizational ladder and/or protect themselves. That sort of individualism and competition is squarely at odds with the solidarity that defines labor movements; it’s hard to come together and fight management when you want to be management. Plus, as Nikil Saval writes in the truly great book Cubed, “unions promised one thing above all — dignity — which white-collar workers claimed they already had.”

The deeply American fantasy of working your way from entry-level worker to the C-suite made it good business sense to resist. Instead, many of these workers — particularly in the ‘50s and ‘60s — placed faith in the benevolence of the company. They had been treated well; they would be treated well. Who needs a union?

And you know what, they were treated well! These white-collar workers had pensions, they had very real job security, and they made good money that made a middle-class life possible. Yes, they were almost all white men, but those white men trusted the other white men, white men whose place they could possibly one day take.

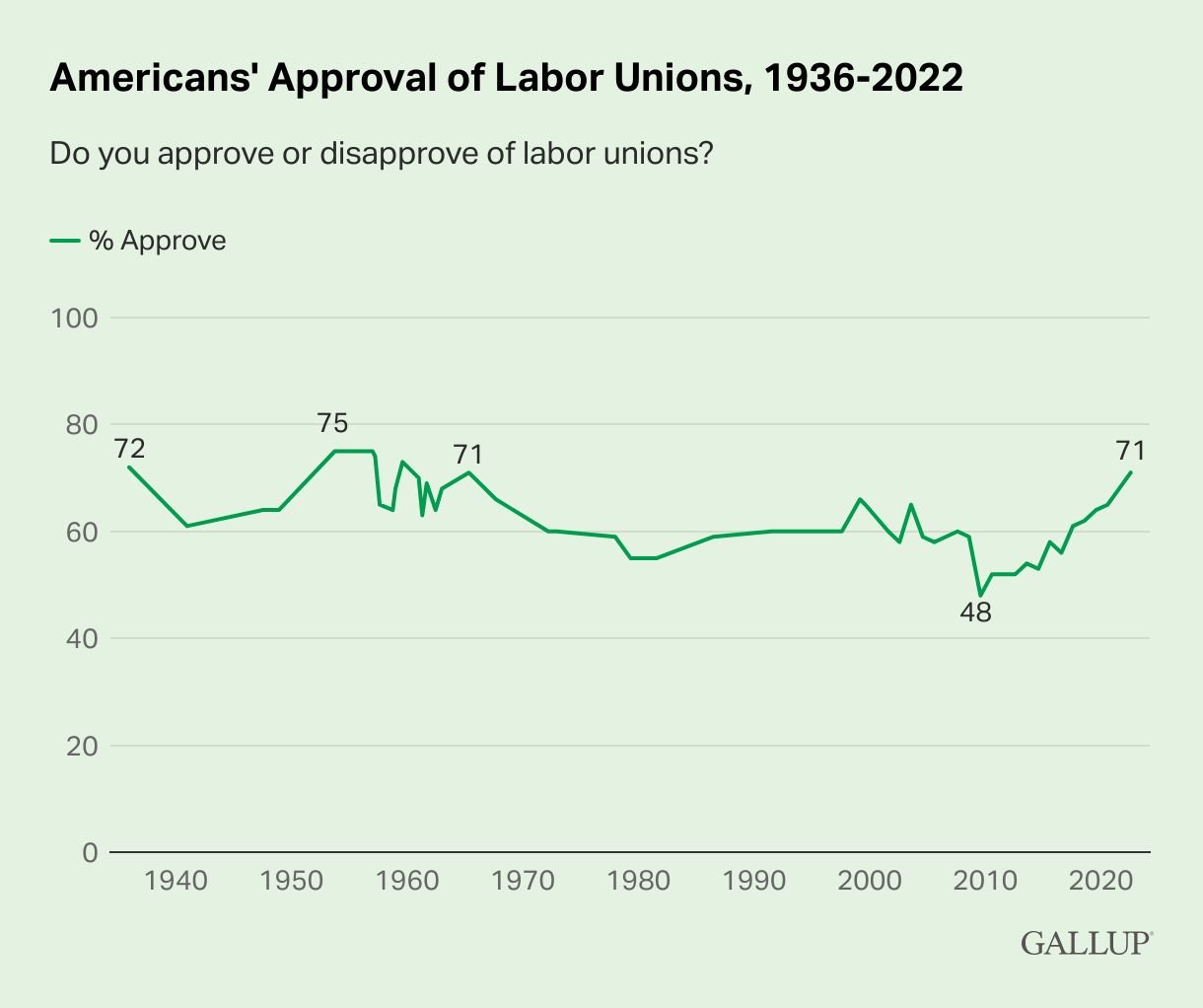

But then the so-called “golden age” of the American economy began to fade. Layoffs, restructuring, and downsizing destabilized the gentlemen’s agreement. But unions were under assault, framed as a cause of layoffs (unions got too greedy!) instead of a primary form of protection against it. In 1979, Americans’ approval of labor unions dropped to a historic low of 55%.

Unionization was still strong in public sector jobs, but private sector white-collar workers turned inward — buying productivity books, putting in longer hours — to create a sort of forcefield against layoffs and downsizing.

I talk about this a bit in Can’t Even, but if your parents were white-collar workers during this time, you were probably exposed to some form of this behavior. Maybe you heard news stories about the growing trend of “workaholism,” or remember that the primary characteristic of Stacy’s dad in The Babysitter’s Club was that he was a workaholic. Or maybe your parents bought one of the dozens of books that came out during that time trying to teach people to identify and treat the symptoms. I’ve bought a lot of these myself on eBay, and they’re all bad in similar self-helpy ways, in part because they utterly misdiagnosis the source of the behavior. These workers weren’t addicted to work so much as terrified of losing their jobs — and as Barbara Ehrenreich pinpointed, falling out of the middle class.

I’m going off on a “how did middle-class millennials and gen-x internalize these lessons from their boomer parents” tangent here, but it’s all to emphasize that overwork has been a pathology and a solution, a part of the office status quo, for decades. Digital technologies just expanded the life territory available for colonization. First, it was that you could bring your laptop home. Then, it was that you could bring a computer the size of a phone everywhere you went. “Shooting off a quick email” while you’re waiting for a wedding to start has become pretty standard behavior. Earlier this year, I found myself sending a bunch of work emails….from a ski lift. The “triple-peak day” (working intensely in the morning, after lunch, and then again after dinner) is just the way things are.

I still believe that companies are capable of creating unbreakable guardrails that protect us from our own worst habits. Companies can enforce PTO minimums, and not just discourage but enforce breaks from communication; they can backfill appropriately and refuse scenarios in which giving 120% is the only way to complete the amount of work that’s expected. You can even give workers flexibility for that three-peak day, if that’s what they want — so long they also underline that the times between the peaks shouldn’t be for work.

I also still think these policies serve organizations well in the long term: they reduce burnout, and turnover, and sloppy work. But most companies don’t think in the long term, at least not when it comes to employees. Leaders are more than happy to exploit workers’ most anxious or engrained inclinations towards overwork. There will always be another worker willing to sacrifice (their mental and physical health, their commitment to their communities or their families or their partners) for the sliver of stability and prestige promised by white-collar work.

As individuals, the majority of us are simply not strong enough to refuse this ever-expanding standard. We’re too wed to our dreams of advancement to yoke ourselves to the coworkers with whom we are implicitly competing. Instead of figuring out how to connect all the lifeboats and ditching the ones with holes in the bottom, we keep frantically bailing our own.

I do think that dynamic is changing — especially as that sliver of stability continues to shrink and solidarity in general becomes more speakable and less stigmatized. I’m thrilled about these growing movements, and regularly use the newsletter and podcast to publish on and promote worker solidarity. But we have to remember that union membership is still the lowest it’s ever been: just 11.3%.

How do we explain skyrocketing support for unions with record-low membership rates? Well, there are decades of anti-labor legislation on the state level and the continued weakening of labor law on the federal level — coupled with a Supreme Court majority that loves corporations so much it wants to marry them. But equally to blame is the “fissuring” — to use economist David Wiel’s term — that makes unionization difficult if not impossible. What does fissuring look like? Subcontracting instead of directly hiring. The freelancification of entire industries. Mislabeling employees as “independent contractors.” Allowing corporations to not actually employ the people who do work for them, and thus shirking their obligations as employers. Letting the loopholes get larger and larger and larger, to the point that the loophole itself has become the standard.

So why haven’t we attempted to address that? Why do our labor laws still assume a workplace from, oh, 1960 — instead of the workplace of today? Conservative business interests, of course, but there’s also a general lack of political will.

And here’s where overwork culture and apathy around worker protections become most pernicious. If bourgeois voters don’t voice revamping labor laws as a priority — or, more to the point, if the donor class that controls the political agenda doesn’t see it as such — then it’s not one. And you know who the donor class is made of? A whole bunch of people who’ve been overwork-pilled — and who don’t see why labor protections should be a priority. People can, and should work as much as they’d like.

Unionization protects individual workers. But at its heart are some fundamental beliefs about what work can and should be. It should not mangle or break your body. It should be dignified, and pay a living wage. And it cannot and should not be the only thing to fill your days: it is part of life, but only part of it. In this way, the labor movement was and is a movement for a better, healthier, society — even if that necessitates leaving profits, particularly profits that enriched those who already had the most, on the table.

Decades ago, office workers rejected that understanding of work in their quest for a larger slice of the pie, believing that their class or education level or title would always protect them from the larger indignities of work. Now, we see the logical conclusion of that bargain: a society in which overwork is so thoroughly normalized that anything less is interpreted as “lazy,” “lacking hustle,” or “your generation doesn’t want to work.” On Twitter, I’ve seen plenty of self-proclaimed progressives call the protests against changing the French retirement age the actions of an entitled society with no work ethic — instead of understanding that our reaction is deeply colored by the understanding that people should basically work until they die.

Overwork culture is the ideology of the “right” to work at its most perverse. It may monetarily advantage a handful at the top, but the societal damage is tremendous. Most of our acute societal ills are directly tied to poverty, and as numerous studies and pilot programs have shown, could readily be ameliorated by the very simple step of giving people money, whether through programs like the child tax credit (a tremendous success) or UBI (read a great, nuanced explainer here).

But there are second-tier problems that spiderweb around overwork — problems related to community-building, child and eldercare, community wellness, overall health outcomes and plain-out happiness and satisfaction and civic engagement. Turns out it’s incredibly hard to build community, to forge social safety-nets, to agitate for larger social change, to even give and receive care when you’re dedicated, willingly or not, to the culture of overwork.

Maybe this doesn’t sound familiar. Maybe you told overwork culture to fuck off during the pandemic or a decade ago, maybe you live elsewhere and have always considered it a sort of pathology. But maybe some it — the struggle to find the time to do anything but work and raise your kids and recover from work, the philosophical support of unions but a struggle to see the need for one in your workplace, a general inurement to overwork culture — feels comfortably real.

Maybe you feel like you’ve woken up and realized that you’re pretty bad at community, bad at leisure, bad at rest, bad at sustaining friendship….bad at most things, really, that aren’t work. At that, you’re an expert. And in that case, it’s worth asking yourself, again and again, until you can stare the answer straight in the face: at what cost, and for whose benefit? ●

Previously on Culture Study:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

“Women don’t step back from work because they have rich husbands. They have rich husbands because they step back from work.”

I am a woman who stepped back from work for/with a rich *wife*, and we talk all the time about our conscious decision to do that—neither of us is under any illusion that she miraculously, alone, by her own white-male-esque virtue, got a 15% raise or is going to make partner or brought in a dozen new clients the year and a half after I quit my job. We both understand the work I do (literally everything else) is grueling and not particularly enriching but essential and allows her the focus she needs to compete with the men at her firm.

AND YET it’s still exhausting swimming against the current of “real” work = good, homemaking = basic, easy, stupid, especially as we increasingly understand that we’re complicit in the seepage of overwork culture to people who don’t have our privilege, for whom it isn’t a choice. I have an MBA and recognize that it’s just good business for our household for one of us to stay home, but I also feel compelled to tell everyone I have an MBA so they don’t think I’m “just” a spoiled housewife.

I don’t really have a point other than to say it all sucks, and also that the book Bullshit Jobs is what convinced me to quit and also made me a UBI convert.

This is a big part of why I went freelance. I make less money and have less stability, but I decide when my workday starts and ends. I say "no" to projects I don't have capacity to take on. I step away when I need to go to the dentist or take my cat to the vet on a weekday morning (or to grocery shop, if that's when it makes sense to do it!). If someone emails me at 6pm on a Friday, I respond the following Monday.

I recognize there's a lot of privilege at play that allows me to work this way, and part of the reason I have enough of a network to do it is that I worked for a decade in office jobs that did not respect balance or boundaries, and was generally successful at it. But I honestly felt like the only way to push back against unreasonable expectations was to not be an employee anymore. And I think it's pretty fucked up that it came to that.