There are Stories in the Data!

Talking about the census — "a continent spanning art project, an absurdly large social dance" — with Dan Bouk

Many of the people who read this newsletter the most are those who haven’t yet converted to a paid subscription.

Is that you? Do you keep telling yourself you’re going to subscribe but delay it because your credit card is in the other room? If you have the means, consider paying for the things that have become important to you. (If you don’t have the means, as always, you can just email me and I’ll comp you, no questions asked). Subscriptions make work like this possible.

The first time I heard about the census, I thought it was the coolest, weirdest thing ever. I was in early elementary school, and my teacher must have been doing some low key census propaganda, readying us to go home and cheerlead our parents into filling them out. It was the first time it was happening in TEN YEARS, which was basically my entire life! There were detailed questions, and you got to give detailed answers! This Type-A Nerdy Kid thought it was THE GREATEST!!!! (I also really, really, REALLY wanted to be a Nielsen family; that never happened)

I have some vague memory of filling out that census data on our kitchen table — I think my mom was somewhat mystified by my enthusiasm — but when you’re nine, there just aren’t a lot of ways that you feel counted.

My recent thoughts about the census have largely been related to white hot anger at the Trump administration’s mishandling of its execution, but when I saw this rave for Dan Bouk’s new book on census data in the New York Times, that old avidity emerged again. I felt the same way reading the book as I did waiting to fill out our family’s census form. It’s such a weird and wondrous thing, this commitment to knowing who we are — even though its execution has never not been flawed, as Dan and I talked extensively about below. Even if you weren’t that wacko kid checking the mailbox for the census form, I think you’ll find Dan’s particular approach to the stories in our census data engrossing. (There’s a reason it’s one of the Times’ 100 Notable Books of 2022).

Be sure to share your own census curiosities in the comments below, ask questions, come talk about your census stories and the Discord — and buy the book! You can find Democracy’s Data here. (All affiliate proceeds from Bookshop go directly to Culture Study Mutual Aid)

AHP: Your bio reads that you research “the history of bureaucracies, quantification, and other modern things shrouded in cloaks of boringness.” Can you tell us your route to thinking and caring about what you think and care about?

DB: It was, to begin with, my parents’ fault.

When I was teenager growing up in a suburb of Rochester, NY, my mother was teaching writing at Monroe Community College and my dad researched image quality for Kodak. I grew up drawn to each of their worlds. In college, I tacked back and forth across whatever line separates the sciences and humanities. I completed a degree in computational mathematics, which I ended up choosing because it had relatively few requirements and so left more time for me to take courses about Shakespeare or religion in American literature. But I was turned off by the way my math classes felt disconnected from the beating heart of humanity. Eventually I discovered history. As a historian I could learn about real people and think about how societies function, without having to give up on the detective-work thrill of reasoning from evidence.

I don’t use my mathematical training that much anymore. But that training has played a major role in setting me on my present path. Many historians---heck, many people---are uncomfortable around numbers and calculations. I’m not, and neither are a lot of people who make really important decisions about our political or financial lives. So I’ve made it my goal in life to tell the stories that are too often obscured by quantitative decision making. I wrote my first book about how life insurance companies justified different forms of discrimination and how they valued lives. This new book is about the census and how people are represented in politics and in facts about the nation. Next up, I’m going to try to make the New York City budgeting process seem as clear and compelling as it is consequential. If I succeed it will even be fun to read about.

When I say something is “shrouded in cloaks of boringness,” I mean it’s an area of life that really matters, but that has been made to look uninteresting. My service to society is to try to find a way to reveal hidden drama in stuff that seems dry and dull. Luckily, there’s a whole community of people who share that mission. Folks, can get a taste of what is out there from this Primer on Powerful Numbers, written with Kevin Ackermann and danah boyd.

Can you talk more about the idea of a “data set as text” — both in terms of the census data set, but also in terms of, say, polling data sets, or the American Time Use Survey data set, or the data set that Peloton or Instagram is pulling about user behavior? What’s the risk of ignoring or eliding these data sets as narratives with a point of view?

When I say a “data set is a text” I am being quite literal. It might sound like a metaphor or analogy, but every data set has one or more authors (like other texts) and belongs to a genre tradition (like other texts) and can be read or interpreted in various ways (like other texts) and takes up physical space on paper or in a hard drive (like other texts). You get the picture.

I had an “aha!” moment in 2017 that really got me started on Democracy’s Data. As a historian I had looked at plenty of historical census sheets. They’re valuable to researchers who want to figure out basic facts (age or occupation, for instance) about historical figures who aren’t famous. They’re the basic building blocks of genealogical investigations too. But in 2017 I asked myself, really for the first time, who were the authors of these facts?

The manuscript census form suddenly looked different.

There were the printed parts: those were designed and controlled by a small group of bureaucrats and political officials. To the extent that most people think of the census as having had an author, they probably think of those people. They’re the ones who decided what questions would be asked and the sort of answers that were acceptable. They made controversial choices, by, for instance, setting out a menu of acceptable racial categories. In 1940, that meant that “Hindu” or “White” were official races, but “Mexican” was not.

But the handwritten responses to each question, the place where this data all got personal, all resulted from a conversation. It was a kind of dual authorship. An enumerator asked a question, a person answered. Something got written down. How they landed on that answer is now usually a mystery. Maybe the enumerator decided. Maybe the person on the other side of that doorstep worked out a suitable reply. Many lives—really all of them—are too complicated to be adequately fit into a form. But one way to understand social privilege is that the forms you fill out were more likely to have been designed to assume your circumstances. And so people who have been marginalized may have needed to fight harder to be accurately represented. That’s a truth that the poet Langston Hughes captured really well in his poem, “Madam and the Census Man.”

There were more authors for census data too. There were editors who went over responses and made sure they employed sanctioned categories. There were clerks who punched data into paper cards and others who ran tabulating machines that churned out statistical tables.

So, what do we miss or lose, when we don’t see a data set as a text. We miss the mess. We also miss the beauty. I see something almost miraculous in the process I just described. It's a continent spanning art project, or an absurdly large social dance.

Now, census data is a best-case scenario. It’s under democratic control and meant to treat each person equally, although it has frequently failed on that count. It’s remarkably transparent. Data sets built to make a social media platform run, to generate profiles and sell ads, those have stories behind them too. But they’re much harder to tell, the people they represent have much less say in their construction. So they’re art too, perhaps, but worse art.

Can you describe some of the ways that the census has elided or discounted different “types” of people — and the attempts to modify it to “catch” those people in the data? What are the inherent problems with trying to modify an existing data gathering apparatus to identify people it was designed to ignore?

I’ll give one example that I think gets at this question well. Early in my research, a fellow historian, Ansley Erickson, told me about a label she came across in a 1940 census record. It identified one woman as “partner” to another. What did that mean, Ansley asked? I did not know, but I really wanted to know. It was an intriguing mystery, and also one that felt personal. My spouse of many years had recently come out as transgender and we had begun searching for new terms to explain ourselves. We were trying on “partner” in our own lives, while I was beginning this investigation.

In the book I explore this mystery in much greater length, but it is very much a story of finding a way to include people who weren’t imagined to exist. The census was designed for straight, patriarchal families: I mean, the paper punch cards had a place for “head” and then a place for “wife,” instead of “spouse” or “husband.” But many people lived in households that did not fit that assumption.

“The fiction of the census is that everyone is in it,” according to the theorist of nationalism, Benedict Anderson. And, he continues: “that everyone has one—and only one—extremely clear place.” Partners were people who didn’t have an extremely clear place.

In the manuscript census records we can find them and they reveal all these different aspects of American life in 1940. We find queer couples who were likely intimate partners; we find men and women separated from their spouses by the great migration of African Americans; we find workers in the colonial territories of the United States living together in work camps attached to sugar plantations.

The partner label gave some people, some communities, or some enumerators a way to make sense of folks and to fit them into households in the way the person or the enumerator could understand. But once that was done, the Census Bureau’s editors and tabulators no longer needed the partner label. All those partners disappeared when the final data tables were released, absorbed under the umbrella terms “lodger” or “roommate.” They remained hidden for the 72 years that those individual census records were kept confidential.

I think most progressives are accustomed to messaging about why the census is important — the more people who are counted, the more funds that are allocated. My understanding of census-avoiders has always been a stereotype: libertarians who don’t think the government should know their business. But it’s more complicated than that. Can you describe the historical resistance to the census, particularly the income-reporting component? What does that resistance (and the way compliance has been propagandized) tell us?

In preparation for the 1940 count, the Census Bureau urged people to cooperate. Indeed, rather incredibly for our ears: “Cooperate” was one actual slogan. Consider the iconography in this 1940 stamp, with an Uncle Sam figure filling in names on a scroll, making a list of every American. When a human enumerator came to the door, that person came in the name of Uncle Sam, in the name of the nation. They also had another more socratic slogan: “You cannot know your country, unless your country knows you.”

But 1940 was a presidential election year. Every two decennial censuses, presidential elections coincide, and they often drag the census into partisan fights. So, when the Census Bureau decided to start asking about individual income in 1940 that became a lightning rod for criticism, in large part because of a campaign driven by a republican senator from New Hampshire, Charles W. Tobey. The Roosevelt administration wanted income information because it was coming to believe that it was the government’s business to support each person’s economic flourishing. Labor unions wanted the information too, so they could know what the standard of living was across the nation. And big business wanted income data to facilitate its marketing efforts.

Many Americans recoiled at the request. How and why they recoiled surprised me, though. I expected that most of the fight would be about the dangers of centralized authority or information. There was some of that, with people writing letters equating the income questions with the tactics of Nazi secret police. But the majority of fears I found expressed in the archives were much more local.

There’s this really revealing letter, written by a New Hampshire widow to Senator Tobey. The letter writer said she did not want to answer the income question. She then promptly proceeded to tell the senator how much money she earned! I laughed out loud in Dartmouth’s rare book room, which houses Tobey’s papers. The point, I realized, was not that she objected to the government knowing her income. She objected to telling an enumerator, who was a real person from her community and likely someone who was friendly with local democrats, who she did not like. Distrust of one’s neighbors proved to be a really important driver of distrust in the census.

I like to ask historians about their favorite archival find — can you share one or two?

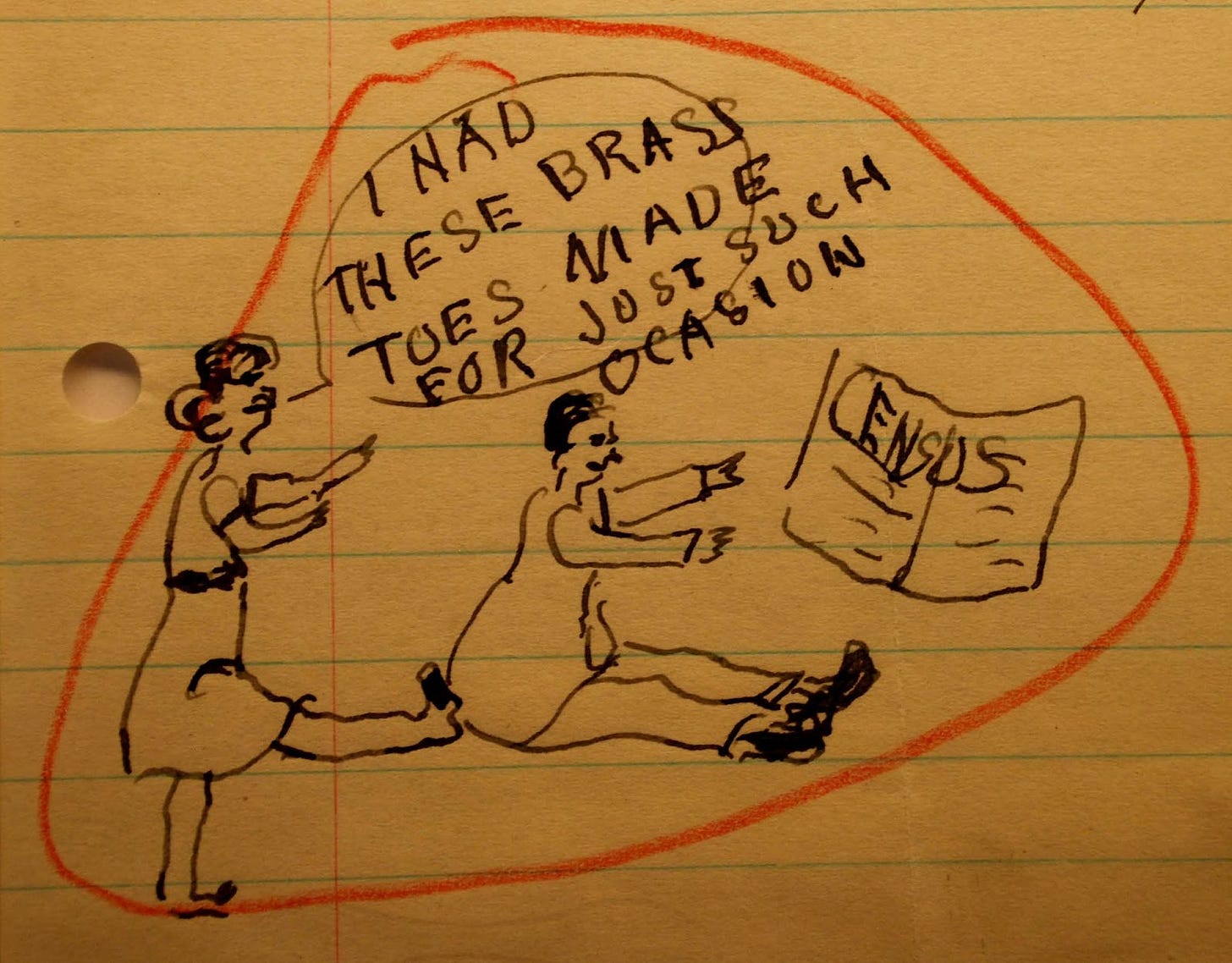

One day as I was reading through the letters sent to Senator Tobey, I found the most remarkable drawing, appended to a letter written by an Indiana grocery clerk named Florence Doud. She imagined what she would do when her doorstep was darkened by some enumerator (who this time would look nothing like Uncle Sam).

Here’s the drawing:

I, for one, had never heard of brass toes!

Of course, my next thought was: did she do it? Did she (literally!) kick out her enumerator? What happened?!

So I went to the census records to find out, and I did find evidence of a kind of census protest. I don’t want to give it away here, but I hope intrigued readers will check it out in chapter 6 of the book…

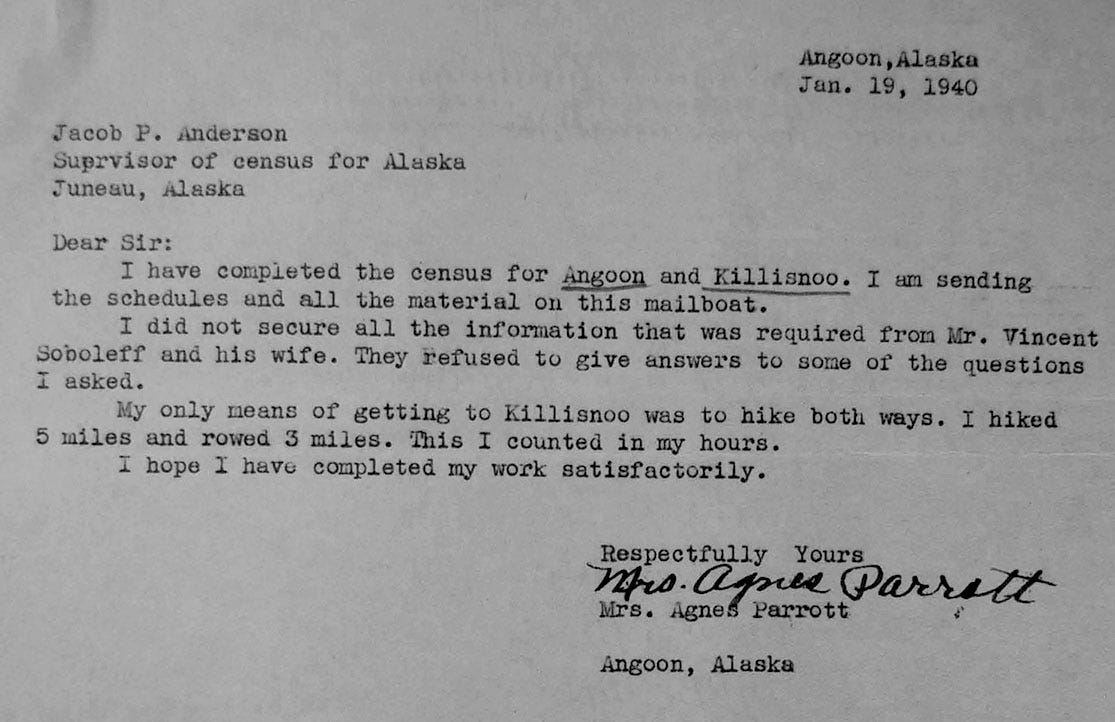

And then there is Agnes Parrott, who showed up in a territorial census file for Alaska. She did not make it into Democracy’s Data, but I was and am tantalized by this note about an eight mile journey by foot and by oar, which included its own census resisters. That story, upon unspooling, looks like a fight about the income question, again, but this time also inflected by a white shopkeeper’s distrust of the better educated Parrott, an Alaska Native.

That story did not end up in the book, but readers can find it here, along with a discussion of how they too can access the census’s archives.

People are very familiar with science labs — but can you tell us about your history lab?? I want to know everything, including how it contributed to the writing of Democracy’s Data.

As an undergraduate I worked in a cognitive psychology lab and at a laser fusion research institute. I enjoyed how in those jobs I got to do challenging work alongside other talented, engaged people. Then I became a professional historian, where collaboration is relatively rare, and while I would not say it was lonely, I did feel like it was needlessly lonesome. So, I decided to recreate something like a laboratory atmosphere at Colgate, which is a small liberal arts college where we only teach undergrads. Now, I hire 2 to 4 undergrads at a time and we meet every week or so. In those sessions we do some historical digging together, interpret tricky documents, and talk through whatever we’re puzzling over. Then we go off and do more digging or analysis separately. I won’t speak for my lab members, but those meetings are often highlights of my week.

And when it came to attacking a basically limitless topic like the census, the lab proved essential. Lab members contributed in two closely related ways: they helped comb through the haystack looking for needles and they helped define what a needle was in the first place. What I mean is that their own interests and ideas about what mattered could help me figure out what was worth writing. I threw out lots of ideas, for instance, but the question of how “partners” appeared in the Hawaiian census was interesting enough to Ethan So that he completed a monumental study, closely reading a huge portion of the Hawaiian census sheets and counting partners, while also noting patterns or peculiarities in the records. Or Andrea De Hoyos picked up on the topic of where, how, and why some people were labeled “Mexican” as race, even though that label had been officially disallowed (which meant that all those individuals so labelled were later recategorized as white). So Andrea read through entire enumeration districts in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona and helped me identify a district that I could use to tell the story in the book.

Our research method linked archival materials to census records. So lab members might help me find archival collections. It was Ethan who first identified a rich trove of records in Mississippi, for instance. And then I would make a trip to take thousands of pictures of archival documents or arrange to get copies sent to me. Some of these documents I shared with the lab and we worked together to see if we could find the people mentioned in them in the census’s records, while also looking for strange or interesting stories. In that way, Emily Karavitch identified a sheaf of letters sent by income-question protestors. The letters were themselves unremarkable, but Emily discovered through the census that the writers all worked together in the same government office: they were state officials who administered the poor relief system. It was their job to ask people seeking assistance about their income, which must have informed their own anger at the prospect of someone asking them about their own finances.

I credit these contributions in the main text of the book, which is not something I usually see in history books, but which I thought was important and which I’d like to see more. But even saying that, those call-outs are just a sample of the contributions that Andrea, Emily, and Ethan made. And I haven’t mentioned Kevin Ackermann, who did a ton of digging at the National Archives, or all my co-workers at the Data & Society Research Institute or the Census Quality Reinforcement Taskforce who let me tag along as they researched and supported the 2020 census.

The cool thing about the census is that almost everyone is in it and the cool thing about studying it has been that it has allowed me to work with so many wonderful, engaged scholars and advocates.

You ask the pretty stunning question in the intro: What is our democracy, if this is its data? After spending so much time with said data, do you feel like you can answer that?

Here’s one way I answer that question, in the book’s conclusion, riffing on a claim made a Census Bureau official in the 1930s:

“Every person in the United States, however insignificant he may be, has a permanent place in the history of the country, for a record of his personal life is made by the National Government every ten years and filed away in the government archives. Nobody need feel that he merely lives and dies without the facts about this existence permanently recorded.” The bureau official skated over an important caveat: some people never got counted, whether because they chose to avoid the enumerator or because the census failed to look for them in the right place. Those people, who tended to be very young or poor and unhoused or from disenfranchised racial minorities, don’t appear in the records. In this case, as with the preservation of confidentiality—which was violated to such devastating effect during World War II—the actual practice fell short of the ideal. Yet the ideals still mattered, and the census strove to attain them. That, ultimately, was what drew me to study the census in the first place. This data teems with the stories of Americans from all walks of life, the sort of stories that a historian cannot find anywhere else. In telling such stories, I aim above all to affirm each person’s dignity and advocate for the inherent, equal value of every individual, even or especially when the census itself did not.

Our data can only be as good as our democracy, as that passage suggests.

The ways that many people go uncounted often reflects failures in our democratic system. For example:

Some of the highest rates of undercount in 1940, especially of African Americans, came in Washington, D.C. I don’t think it is a coincidence that D.C. also had no representative in Congress to look out for its residents.

American democracy failed dramatically when the government incarcerated 120,000 Japanese Americans during WWII, weaponizing census data in the process.

And since 1941, American democracy has been locked into a game of musical chairs. It used to be that the House of Representatives increased in size as the population increased. But the size of House has been frozen for a century now, while the number of people being represented has tripled. Before I began Democracy’s Data I knew nothing about this. Now, I (and others) think it’s well past time to enlarge the house.

So, what I guess I’m saying is that democracy’s data suggest to me there’s much more work to do.

Finally: Best place for people to find you on the internet?

I welcome new readers at my occasional newsletter, Shrouded and Cloaked, or my even-more-occasional blog. Readers can e-mail me at dbouk [at] colgate [dot] edu too. I’ve had a special stamp made from that 1940 “Cooperate” image and I love nothing more than sending people signed and stamped bookplates. Just write me and ask for one!

You can find Democracy’s Data here.

Do you want access to the weekly link roundup and “Just Trust Me?” Do you want to be part of a community figuring out how to care for one another, even from afar? Or maybe you just want to feel like you’re supporting content that’s valuable to you. Here’s how you do it:

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads (this week’s is Friday thread on perfectionism and ambition was particularly good), and the rest of the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece and the latest episode of the podcast, plus really useful threads for Job-Hunting, Houseplants, No Kids Club, Chaos Parenting, Fat Space, Productivity-Culture, and so many others dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I'm a data and government info librarian, so read this newsletter as soon as I saw it this morning! (And I'd already ordered this book for my library a few weeks ago and am psyched to read it).

I don't often look closely at the stories in the Census in the work I do, but am endlessly fascinated by them. When the Census 1950 enumeration scans were released earlier this year, I looked up all of my family members I could think of and even in a few lines felt really connected to them -- for example, I learned my great grandmother worked as a Census-taker herself. My grandfather (who died before I was born) was a veterinarian in a rural agricultural area and under "how many hours per week do you spend working?" he had an emphatic "???", which told me that he probably scoffed at the question 🙂

If you watch Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., you know the importance of Census data in unlocking family mysteries. A research librarian used Census data to help me trace the history of my grandmother’s bakery a century ago. The Census is a delightful thing.