"This country isn’t made for us, even though it’s built on our land."

Sterling HolyWhiteMountain on the first annual James Welch Festival

If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, if you open it all the time, if you save it for an escape or forward it to friends and family and have conversations about it— consider becoming a paid subscribing member. Your contributions make this work sustainable, and also make it possible for me to offer free subscriptions for anyone who cannot afford to pay.

Sometimes I still can’t believe the first house I found in Missoula. A small box of a thing, hideously painted, tiny bedrooms, scabby yard. But it was at the end of a dead end street alongside Rattlesnake Creek, a wild and wondrous rushing body of water that most people who’ve never seen a wild river would mistake for one. People in the neighborhood told us: Oh, you live on the writer’s street!

It took me a few months to realize what they were talking about: on the other side of the street, a few houses down, were two gorgeous arts and crafts houses. Blue and green, white trim. James Welch used to live there, along with his wife, Lois, and the poet Richard Hugo, right beside.

I re-read Welch’s Winter in the Blood immediately. Just months before, I had spent several weeks traversing the Hi-Line, where the book is set. Marveling at what a sense of place he created in that book, how the years had changed but so much of that place had not, how deeply Montanan the whole thing felt, how Western, because what is Montana and what is the West if not the ongoing story of settler town on the edge of the reservation. It manages to run alongside yet headfirst into all those other Montanan narratives, almost all of them written by white settlers, that have been canonized over the years.

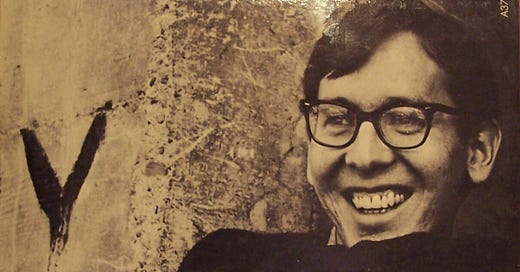

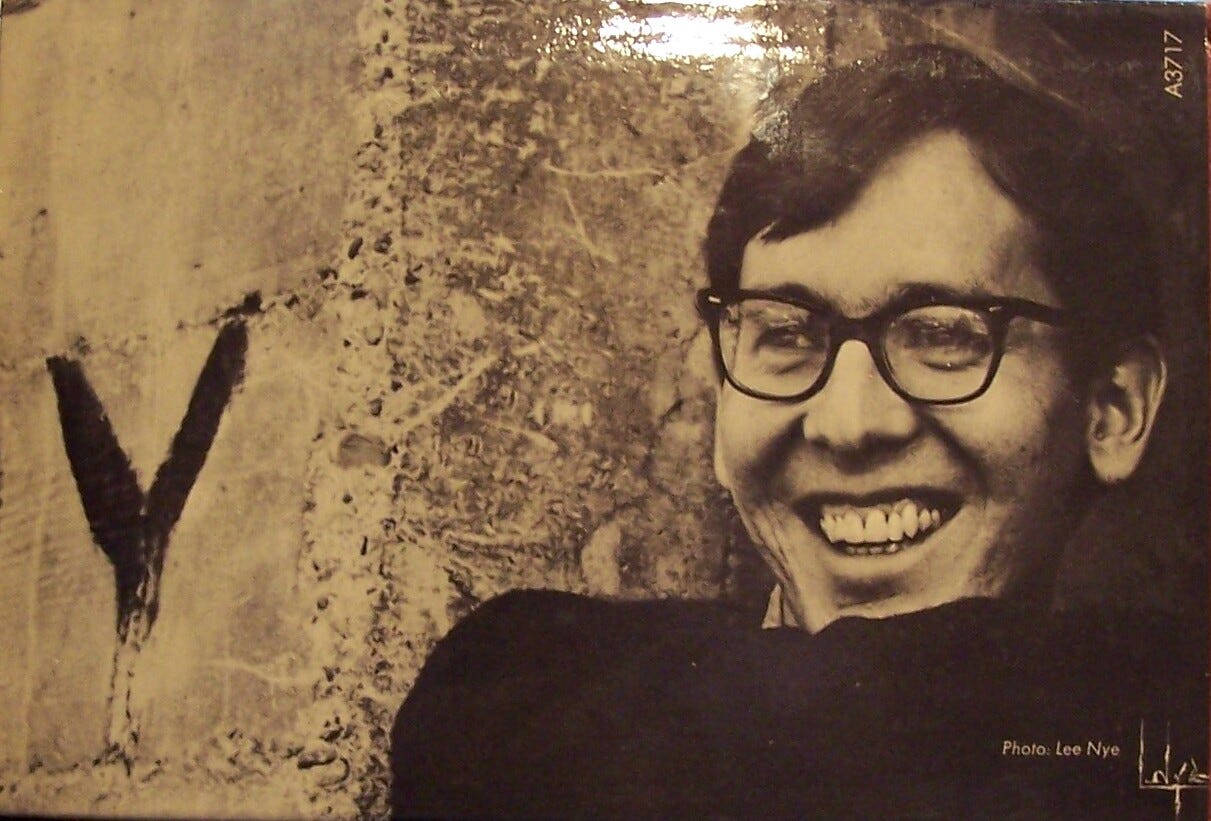

Welch was a member of the Blackfeet Tribe, and spent his early years on the reservation before attending the University of Montana as an undergrad and eventually completing his MFA. He is the author of a three novels (Winter in the Blood, The Death of Jim Loney, and Fool’s Crow, often considered his greatest work) and one book of poetry (Riding the Earthboy 40), and next weekend, July 28-30, there will be a whole festival to celebrate him in downtown Missoula.

Every year there are dozens of festivals celebrating different authors and types of writing, but this one is both different and formidable. It was conceived of and orchestrated by Native people, and will exclusively feature Native writers and artists in conversation with other Native writers and artists: Louise Erdrich, Tommy Orange, David Treuer, frequent Culture Study contributor Chris La Tray, Rebecca Roanhouse, Debra Earling, Tailyr Irvine, and so many more.

Now I could talk about the hypnotic quality of Welch’s writing, that indelible sense of place, the deftness of his characterization, for pages. But I can’t do it, or even come close to describing the import of this festival, the way Sterling HolyWhiteMountain can.

Sterling is the architect. He imagined this thing, a thing of his dreams, and spent years making it happen. He’s an unrecognized citizen of Blackfeet Nation, and like Welch, grew up on the Blackfeet reservation in Northwest Montana. He is also one of my favorite short story writers. Everything of his I read sticks in me like a knife. I mean this as a compliment, to be clear. There’s this dagger of a piece in The Paris Review, and this one in The New Yorker. He writes essays, too, like this one for The Atlantic on the reservation brain drain, and is finishing his first book. When I see something of his, I click it immediately, then actually read it immediately, too. For how many people can you say that’s true?

But don’t take my word for HolyWhiteMountain’s excellence or Welch’s or why this festival is important. Read below, and you’ll begin to get it. I wish I had better words, more superlatives. But believe me when I say this is one of my favorite interviews I’ve done for this newsletter. If you ever click on one of my “just trust me” links at the end of the newsletter, please believe me when I say: just trust me.

If you’re in Missoula or can make it there— go to this festival. You will not regret it. And if you can’t be there but think this sort of work is incredibly important, we collectively work to make the dream of a yearly festival a reality. Culture Study will match every donation up to $1000 — just send me your receipt (annehelenpetersen @ gmail). Here’s how to donate now.

And now, here’s Sterling HolyWhiteMountain.

Can you tell our readers what you love about James Welch — as a “figure,” but also about his craft as a writer?

There are a lot of things I could say here, but what I return to again and again is the simple, direct, grounded quality of the prose. When I read Jim’s work I can very much tell these are sentences written by someone who grew up in Northern Montana, someone who intimately knows the brute simplicity of the land and the vast silence of the plains. Even when Jim is at his most lyrical, as with Winter In The Blood (which is one of the great titles of American literature), there is still an accessibility to the sentences that is familiar to me.

I think there is also something very “reservation indian” about this simplicity (simplicity here does not equate with unintelligent), though it’s hard to argue or break that down because in this instance it’s so intimately tied with the language patterns of the rural plains, which is larger than the linguistic patterns of reservation life on the plains. But it’s something I can feel, it echoes the version of English I grew up with, and maybe more importantly heard, on my reservation, which not incidentally is where Jim spent the first part of his life. So I felt an immediate recognition when I started reading his work, a familiarity.

It’s impossible to finally explain what growing up on the plains does to you, and it’s just as hard to explain what living in a place where though most people are speaking English, it’s an English that is primarily developed from and informed by people whose first language was not English. It’s shocking to think about it now with almost all of our fluent speakers gone, but when Jim was growing up, most of the people older than him would have been fluent Blackfoot speakers. And that changes everything, even though they were likely speaking English. The cadence, the intonation, the language patterns, the timbre of the voices—I can hear all of that in the work, it saturates everything. The Blackfoot language even now, though most of us know nothing of our mother tongue, looms over our lives, a massive shadow whose source becomes more inscrutable by the day. It’s one of those things that is difficult to talk about, but to use that overused phrase, if you know you know. It’s something I can feel.

As for Jim as a figure, the thing about Jim that you realize the more you talk to people who knew him well is that he was nearly universally loved, which is a hard thing to pull off for anyone, but even harder for a writer, as writers tend to be far more fragile, petty and generally misanthropic than most. But bring up Jim’s name, and what you get are responses of affection. People smile when they talk about Jim. I have yet to talk to someone who doesn’t mention how funny he was, or how humble, or, and this is perhaps the most interesting and rare quality of all, but people talk about what a great listener he was.

One of the first stories I ever heard about Jim was from Chris Offut when I first got to Iowa [The Iowa Writer’s Workshop]. He was a visiting writer in Missoula many years ago, and he was just getting his feet under him as a writer, and he was at one of those classic writer parties that used to take place regularly in Missoula. And he was feeling very isolated, I think, very much a hick among the literati as he described it, and at some point in the party Jim sat down by him and asked him a few questions and then listened to him for a long time. And years later Chris was still thinking about this experience of Jim listening to him. He brought it up several times over the next few years.

I think this is very much the listening of an outsider, or someone who has been on the outside the whole of his life. When you start to get a handle on Jim’s life, its general arc, you realize this is the story of someone who was profoundly on the outside of things. It’s almost impossible for us to imagine now, but indians of that generation, they were the first to really embrace, or at least go after, the American way of life. And they did not find that way of life particularly open to them, let alone inviting. But they did it despite the difficulty, and when I think about the odds they faced—I’ve considered this a lot, my dad is one of those people—I’m amazed at the will and desire and tenacity it took for them to succeed. Because the truth is a lot of them did not. A lot of them, and a lot of us still, get lost along the way. This country isn’t made for us, even though it’s built on our land.

One of the great ironies of America is that this country is ours in a way, but we don’t ever quite belong here. And when I hear stories about Jim, what I hear are stories about someone who was an outsider in a remarkable number of ways, and who succeeded on American terms without sacrificing his identity in the process. I think in the end this is the great victory of any indian who has success in American terms: to do that without selling yourself down the river, without becoming a white man’s dog, so to speak.

I only saw Jim once, he came to a class at UM [University of Montana]. I had no idea who he was; I had never heard of him. I had just started to write. But I can still see him very clearly, sitting at the front of the class. He was very soft spoken, and he had that familiar indian gentleness to him, but there was an unshakeable confidence in him also, and that combination of traits—common in indian country but very uncommon outside of it—was deeply familiar to me. That one hour in class with him changed the course of my life. I was deeply fortunate the first indian writer I ever heard speak was also from my tribe.

I’ve been hearing rumblings of this festival for a few years, and was thrilled when Chris La Tray told me earlier this year it was really and truly going to happen. On the website for the festival, the first question in the FAQ is “Why are we holding the festival?”

And the simplicity of the answer is perfect: There is no place for Native writers to talk publicly about our work, with each other. We wanted to create that space.

When I profiled Terese Mailhot and Tommy Orange, I spent several days with them at IAIA (the Institute of American Indian Arts) in Santa Fe, where both of them were teaching in the MFA program from which they both recently graduated. That program isn’t exclusively Native or Indigenous, but I also remember Terese telling me how different it felt to learn and teach away in a place where elevating Native voices weren’t an afterthought, or an embroidery, but at the very core of the mission.

I’d love to hear more about your frustrations with festivals where Native writers are often invited, and how you and the others coordinating the festival have worked to make this one feel different.

I mean, I’ve only published a few stories (my book is…on its way lol) and I’ve only done a few interviews but I’m already sick of the process. There is a set of very basic questions every indian artist is asked, and they are generally all about identity. And nearly never about craft, or artistic influence, or etc. Never the questions white artists get all the time. You can see where that goes. And I’ve sat on panels at festivals, off and on for years, and I’ve talked to a lot of Native artists at this point. And quite literally all of us have the same, basic frustration: people don’t know how to talk to us because they don’t know anything about indians or indian country, so they fall back on asking us about our identities because that’s the easiest thing to do. All questions essentially come back to, “What is it like to be an indian?”

There is a long, long history in this country of a lone indian speaking to a white audience. It goes all the way back to the beginning, and it’s related to this idea that a single indian can somehow speak for everyone. This is partly related to the Western idea of individualism (it’s ridiculous in tribal culture to think any one person knows or could know everything; knowledge is ultimately collective, which is the same as it is everywhere, it’s just that we don’t pretend one person can know everything the way Americans do, or try to) and partly related to the politically efficacious process that was developed by America to accelerate the acquisition—I’m being diplomatic here—of the land and resources that provide the foundation for this country.

Historically, the way most tribal people worked on this continent (I say most because it’s very difficult to say everyone) when it came to making big decisions, was that everyone got a chance to speak. Which meant it took much longer to come to a decision, but when that decision was reached, more people were more likely to be happy with the outcome. I want to be clear that this is not a halcyonic vision of the past; there was always disagreement in the old days, always dissatisfaction. Not because we were “indians,” but because we were and are people, and to be a person is to have individual thoughts and beliefs that generate disagreement at times with others. The point is that we had a different system for coming to an agreement, and that system was and is at odds with the American system. And it was efficacious for America to draw us into negotiations that only required one signature, so to speak, because it accelerated the expansion of the country’s boundaries.

And then you have the Ponca Standing Bear, and his famous speech in front a federal judge, which took place at the end of the trial that ultimately allowed that indians were people under the law. And after that decision, he traveled the country talking about indian rights in the eastern US and Europe. So this pattern, this idea that one indian could and should speak for all goes all the way back, and while in the case of Standing Bear’s speech in court it was a good thing, more often than not that situation turns into a way for non-indian audiences to fetishize and novelize the indian on stage.

I wanted to create a space that more honestly reflected my experience of indian country, which is that everyone is talking, and a multiplicity of perspectives are present and accounted for, so to speak, and I wanted that to take place in front of an audience that consisted of both indians and non-indians—and I want to see what comes out of that. My feeling is that more than a few people, both indian and non, will be completely rocked by what they see. And that’s what we’re looking for: for someone in the audience to have their too-simple understanding of indians and art to be transformed into something more complex, more true, and hopefully funnier.

Also, I want all these indian writers to be in the same space together, which has somehow never happened before, this kind of gathering. I want all of us to be there together and see what comes of it. It’s that metaphor often used in Buddhist circles with regard to the sangha, that of stones in the same river smoothing each other out because they come into regular contact with each other. We’re so accustomed to being the only indian in the room. What happens to the way we speak when that’s not the case?

Lastly, and this is mostly for the long term because we didn’t have time to make this happen the way I wish we could have, but I want this to be a place where younger native people who are interested in art can come and see people like them who are doing what they might want to do, and hear them talk about what they do, and how they do it, and what their lives are like, and how they got to where they are.

It’s unbelievably important for young people to see people they can identify with doing what they — the young people — want to do with their lives. I’ve thought about this for a long time. You know, my dad’s heroes were black athletes, particuarly Muhammad Ali. I grew up listening to my dad talk about these incredible athletes, and it wasn’t until much later that I asked myself why his heroes were black (other than Elvis, which is both funny and very interesting) and I realized you know, that was what he had to look at. He obviously admired all the great athletes of those times, but I think there was a deep identification there that had to do with the (then) outsiderness of the black athlete in the white world.

And I grew up the same way. There were no indians for me to look at and go, There, that’s like me. I get that person. We are only just now reaching a point where that can change, where younger native people can look up to people who understand the life and the place they come from. My hope is that this festival can accelerate that process for younger people, that they can attend or watch the recordings of the talks on YouTube and that will help them move through the problems that all indian artists face with more grace and speed, instead of having to reinvent the wheel like most of us have for decades, developing in relative isolation.

What’s it going to *feel* like? (Other than stressful, because putting on a festival always involves carrying some manner of logistical weight)

I mean, lol. In the beginning it was wild, to see how people responded with such positivity. I never dreamed it would go like this. I had no idea if anyone would want to help me with this, and that for years was the thing that stopped me from beginning, because I knew I couldn’t do it alone, and I didn’t think anyone would want to help. Instead quite literally every person I’ve talked to about it hasn’t only thought it was a great idea, but many of them have offered to help make this thing a reality.

This is one of the things that our ceremonies implicitly teach you if you’re paying attention, that very little (maybe nothing) we do can be done alone, and whatever we might do alone should ultimately benefit other people. It’s fascinating for me to watching the bootstrap mentality at work in this country because the idea that anyone has ever lived their life without constant help from others is just a lie. A ridiculous lie. There is always someone somewhere helping us get to where we need to go. Or they are waiting to help us, and we just aren’t paying attention, which is part of the great picaresque of human life, that we can never quite see ourselves and the world around us. We need each other for that. And that should lead to us laughing at ourselves and each other.

Once we got through that first stage and things started to take shape, it was a lot of fundraising and trying to figure out who we wanted to come, and that took about a year and it was…really stressful until we hit our mark. And then the last three months have been logistics hell, which has kind of turned into one of those things that is like…well it’s like a drug lol. It’s not good for me but there is a kind of high that comes with each task completed, and seeing that we are one step closer to this thing being real.

As for what it will feel like, as we are doing it? I really have no idea. I still have so much to do in the next week that I can’t allow myself to look at the finish line. My hope is that the overall feel and effect of the festival is at least…60% of what I want it to be. Nothing is ever what we want it to be. It’s Plato’s realm of forms thing, where the perfection of the idea never quite makes it into the world. This is always the case with art too. What you hope is that it gets close, as close you are capable of making it with whatever skill you have, working against your shortcomings. I hope everyone has a good time, and comes away from the festival with good feelings. I hope the writers feel appreciated. And I hope there is a moment where I and the amazing people who helped organize the festival can look around see that what we did was good, that the vision we had was good and that it was enough to make this thing worth attending for the audience members and writers.

I think a lot about Welch’s friendship with Richard Hugo — in part because of where I landed in Missoula, and the various ways both memorialized their friendship in different forms over the years, including, most famously, in the trio of poems they wrote (along with J.D. Reed) about the Only Bar in Dixon, which they sent to The New Yorker, somewhat on a lark, and ended up getting published. Hugo’s poem often gets the most attention (to be fair, “This is home because some people / go to Perma and come back / from Perma saying Perma / is no fun” is pretty great) but I love Welch’s the most, that lethal line, “A man could build a reputation here,” which is precisely what I think each and every time I drive past the Dixon Bar, still very much the Only Bar in Dixon. What about Welch’s poetry or that poem (or set of poems) sticks out to you?

Well, I am not a poet, but recently came to an understanding of myself that has been a long time coming. I’m essentially a frustrated musician inside the body of a frustrated poet inside the body of a resigned fiction writer. It was songs and albums that taught me structure, not so much stories and novels, and music in the end is the most powerful and important art form—and I’m guessing the oldest, also. I tried my hand a poetry when I first started writing, but I don’t have the capacity for language that poetry requires—and in the end I’m too narratively oriented as a person. So it’s the country of fiction where I’m spending my life, for better and for worse.

But I have some small percentage of the poet’s sense of language, the lyrical, the way a line turns, and so when I read Jim’s poems, what I’m stunned by is what you identified above, there is something lethal (a perfect word) about his poems, they are dark and driven and lethal with a side of sarcasm and when I look at them there is something unequivocally Blackfeet about them. A fearlessness, a profound disinterest in not saying the thing you need to say, a way of speaking that is unconcerned with how your truth is received. A bold, don’t-give-a-fuckness. The first time I read those poems I was completely rocked by how surreal they were while also being extremely visceral, and by the way he bends language, but also how familiar they felt to me. How does something of the essence of a culture or person make its way into language and how does that language, particularly when it’s on a page, continue to carry that essence? It’s one of the great mysteries of life, to me, that the symbols we create carry something ineffable in them.

And of course there is an anger in those poems. The interesting thing about anger, and this is something Charlie D’Aambrosio used to say when I was at Iowa, is that it can’t sustain a fiction narrative. A lot of people, particularly people of color (a term I’m not comfortable with, in the end, when it comes to referencing native people) when they get going, I think, try to write from anger and it ultimately fails because anger is boring in art because it contains too much self righteousness—and in the end it’s a cover for pain, a way to not be vulnerable. But Jim did something in those poems I’ve hardly seen in anywhere in literature; there is a dark anger that saturates that book. I feel it as soon as I start reading. But what is most amazing, I think, is not that quality itself, but that the anger somehow does not limit the work, does not turn it into a cheap political tract or a sermon. The poems remain, finally and fully, art. It’s a remarkable thing he achieved.

Why does it matter that this festival is happening in Missoula in particular and Montana in general — particularly given the changes in politics, housing prices, hostilities towards tribes and their self-governance, and ongoing attempts to disenfranchise the Native voters who have, in recent history, played a deciding role in Montana’s political trajectory?

It matters because it’s a way of saying, We are here whether or not you want us. We are not going away. And more than that, we are going to keep going forward, we are going to keep living our lives, we are going to keep succeeding despite these attempts to silence us. We are not symbols liberals can trot out on stage when the occasion fits. We have our own voices, our own lives, our own complicated desires—and we’ve always been this way. It’s just that most of America wasn’t paying attention, or didn’t want to. And of course this is taking place on Salish land, next to the bridge they were marched across when they were forced north. America is a country of forgetfulness. I’ve often thought that the real American dream is the dream of living without a past, and Montana is a part of that. And the new Montana, the gentrified Montana, all these people coming in, they’re reenacting the story of conquest, they’re arriving as though this land were a great empty new world just there for the taking.

Well, too bad about that.

You can follow Sterling on Twitter here.

Again: if you’re in Missoula or can make it there— go to this festival. And if you can’t be there but think this sort of work is incredibly important, we can collectively make the dream of a yearly festival a reality. Culture Study will match every donation up to $1000 — just send me your receipt (annehelenpetersen @ gmail). Here’s how to donate now.

Want access to the weekly links and “Just Trust Me?” Consider becoming a subscriber.

Subscribing is how you’ll access the heart of Culture Study. There’s those weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads, plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece, plus equally excellent threads for Fat Space, The Bear, Romance-Are-Great-Actually, Job Hunting, Zillow-Browsing, Buy Nothing, Real and Potential Austen-ites, Puzzle Swap, Home Improvement/DIY, Running is Fun????, Advice, Ace-Appreciation, Books Recs, Home Cooking, SNAX, or any of the dozens of threads dedicated to specific interests, fixations, obsessions, and identities.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I just yelled a bit too loudly to my wife when I opened this newsletter. She’s Kelli Jo Ford, one of the writers featured at the festival! In fact, she’s planning to jet off in the next few days. Thanks so much for highlighting this event and Native writers and artists. What a wonderful interview!

“ We’re so accustomed to being the only indian in the room. What happens to the way we speak when that’s not the case?” This is so well said and I think pinpoints what excites me about the fact that this festival is happening.

Also, wow: “ the real American dream is the dream of living without a past” This resonates mightily.