This is the midweek edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

I don’t have a daughter, but Instagram sure thinks I do. I blame my birthday weekend, back in May. That’s when I was surrounded by women who are the parents of children between the ages of 2 and 7, which meant my phone was hanging out with their phone, my Instagram near their Instagram, and the dark tubes of the internet that communicate to one another about potential shared consumer interests started serving me the ads for Mother-Daughter dress ads that have since filled my feed.

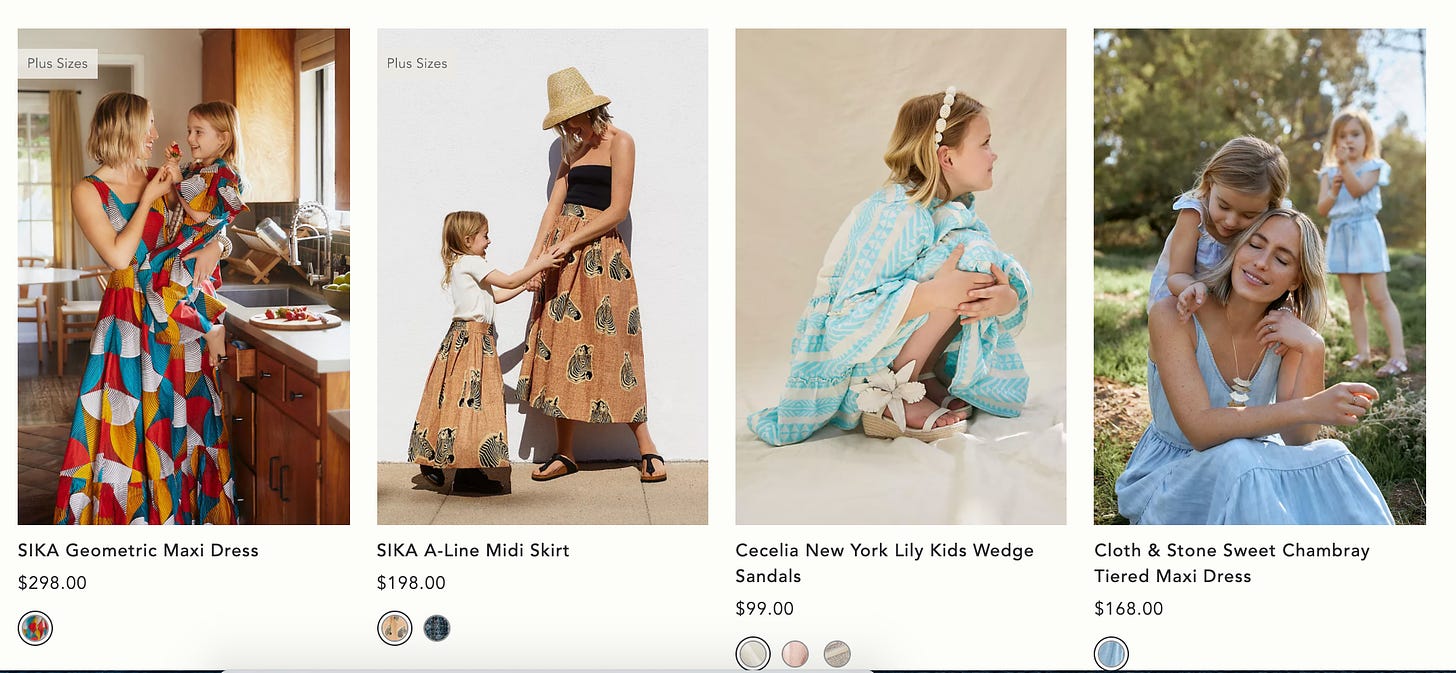

Some are higher-end. Some are from Target. There are a bunch of those brands with good lighting and racially diverse models who somehow all have the same breast size that you only see on Instagram. Maisonette. Doen. Mark and Spencer. Pehr. Christy Dawn. Rolee. One Loved Babe. Alix Cherry. Marks and Spencer. Hillhouse. There are sets from Anthropologie, and Reformation, and LuLaRoe. I asked people to send me Instagram ads when they spotted them in their own feeds, and I received hundreds. They are flowy and floral. Feminine and wistful and demure. And they reach full expression in the Nap Dress.

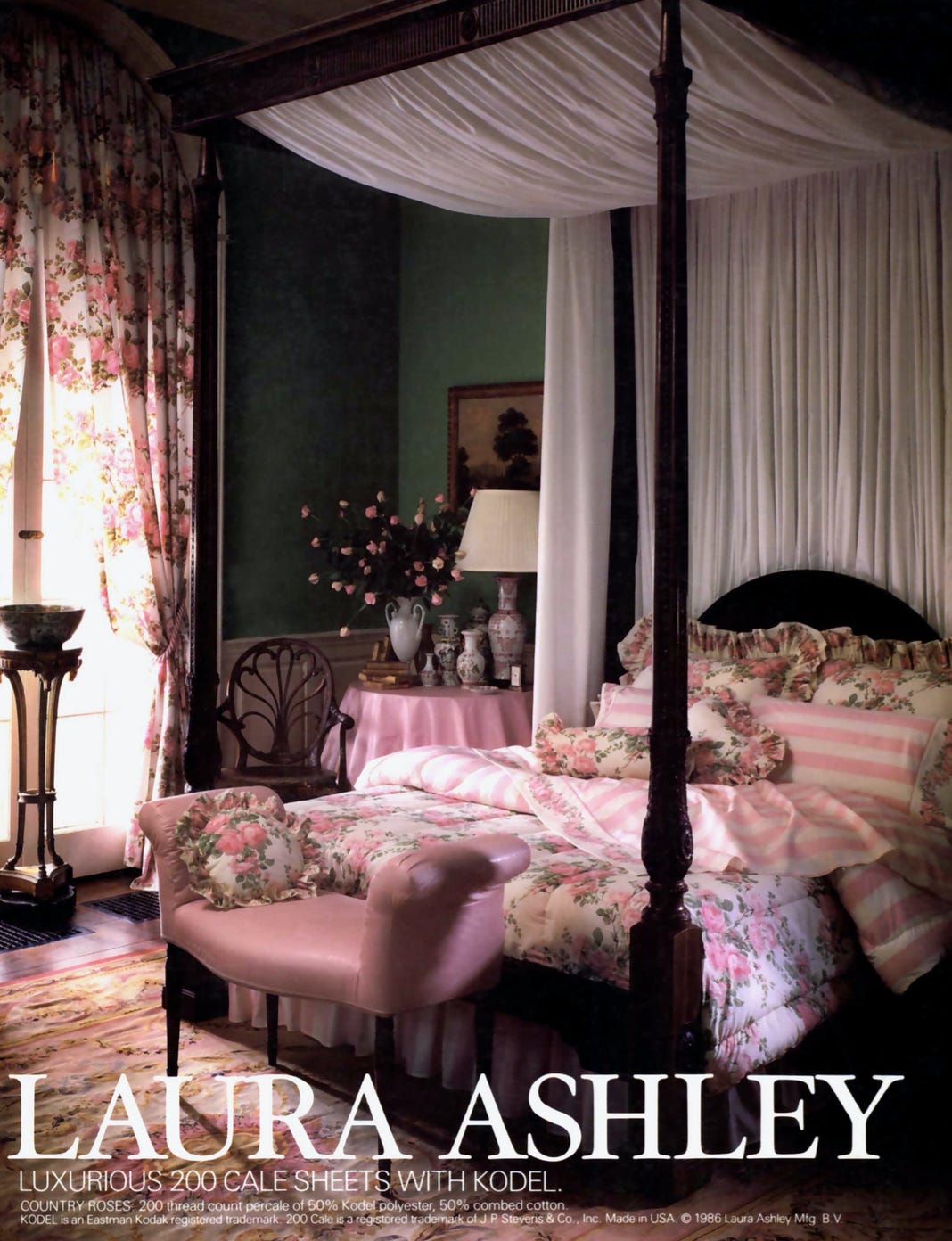

If you grew up in the 1980s and ‘90s, you might recognize the previous iteration of this trend from Laura Ashley. But this is more than the latest iteration of ‘90s nostalgia, and as any fashion historian will tell you, a dress is never just a dress. They are an extension and elaboration of the cottagecore aesthetic, and the pastoral nostalgia and romanticism that accompany it. But it’s more than that, too.

#Cottagecore is rooted in TikTok and YouTube, and primarily propagated by Gen-Z. By contrast, these dresses are targeted at millennial moms of young children, trying to negotiate their post-pandemic understandings of the family. The targeted mom is burnt out, exhausted, ambivalent, and/or resentful of contemporary motherhood expectations. Afters months in close confines with their children, they’re both addicted to and deeply annoyed by their children. They are trying to reconcile the fact that our country does not give a shit about women with the incessant drumbeat of “upholding family values.”

Some dropped out of the workforce to handle care. Others tried to juggle full-time work with full-time caregiving responsibilities. Either way, they have served as their family’s safety net for the last year, and those with middle-class incomes are being targeted by the algorithms that whisper this is your summer uniform amidst the infinite scroll.

And why not? As Gen-Z goes out for Hot Vaxxed Summer, owning the streets of cities with their confidence and cool outfits, these moms are still sorting out which summer camps are COVID safe and counting down the days until those under 12 can be safely vaccinated. What’s the post-vaccine mom-of-young-kids wardrobe? You might have other ideas, but Instagram’s is: a beautiful set of mommy-daughter dresses.

Historically, these mother-daughter dresses have exploded in popularity in times when culture, as a whole, was occupied with reasserting the strength of both the nation and the domestic sphere. Historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell traces the first instance of high fashion mother-daughter matching to 1908, but it wasn’t until the late 1930s, when the United States was just beginning emerge from the ravages of The Great Depression, that what Life called “the mother-and-daughter custom” became popular.

The trend paused for World War II, but flourished, again, in the America-building aftermath, when quiet panic of women’s brief wartime foray into the workplace was drowned in a sea of flouncy, feminine skirts. Christian Dior’s incredibly influential ‘New Look,’ introduced in 1947, was at once a reassertion of abundance — the sheer amount of fabric to required to create the silhouette would’ve been unheard of during the war — but also a rejection of the square and more severe lines of 1940s women’s fashion.

The Mother-Daughter patterns, printed in newspapers across the country, provided a literal blueprint for mothers to not only visually reinforce the bonds of the nuclear family, but clearly delineate their desired future form: I am a housewife, and one day you, too, will be a housewife. As Chrisman-Campbell points out, mothers were also encouraged to sew the patterns with their daughters, one of many means of passing down a necessary domestic skill. The dresses were products, and wearing them was performative, but making them was a sort of training exercise.

The popularity of mother-and-daughter dresses waned over the course of the 1950s and ’60s. That doesn’t mean siblings, in particular, didn’t still dress in matching outfits, or that home seamstresses didn’t make them. They just weren’t faddish. That began to change in the 1980s and ‘90s — and Laura Ashley led the way.

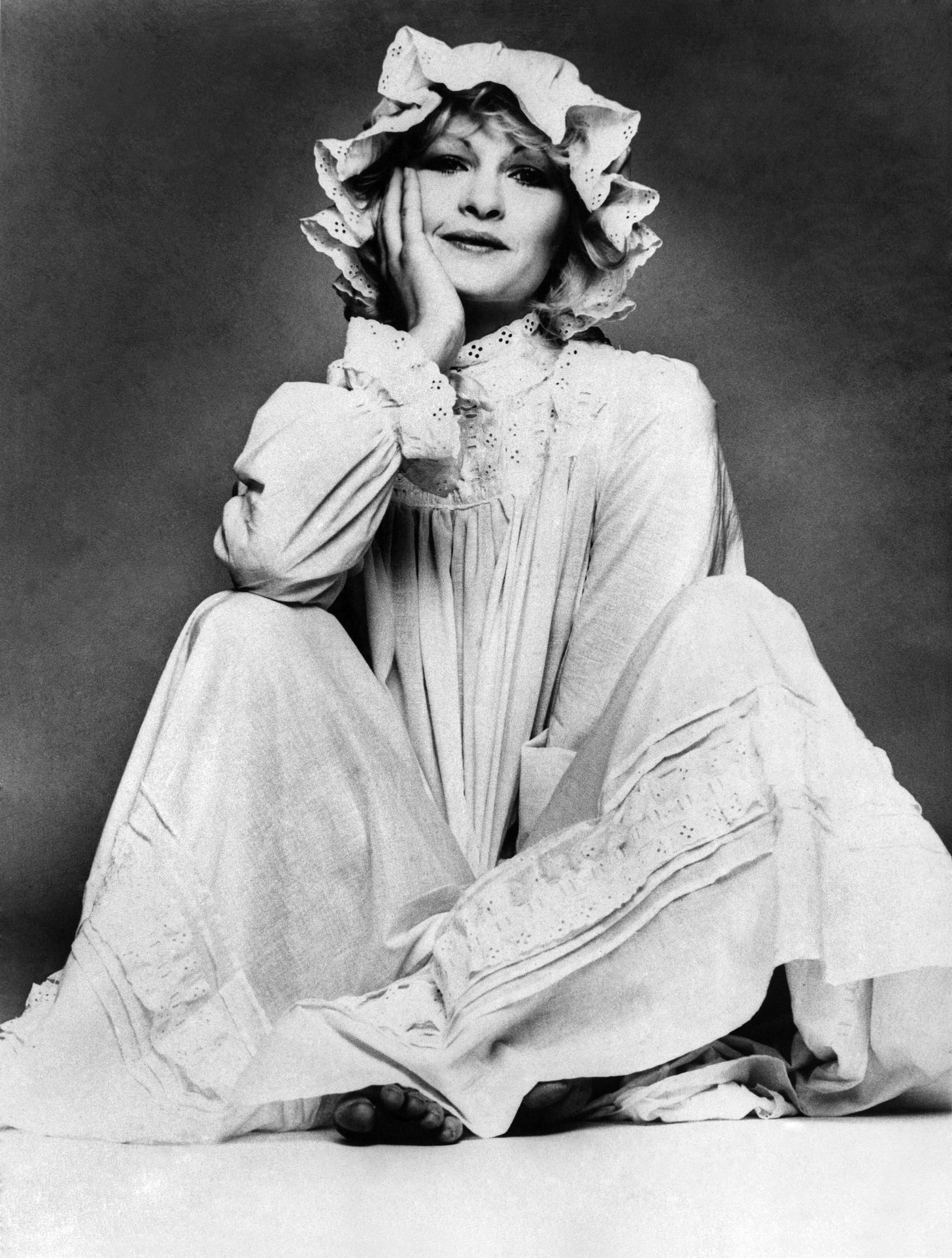

Laura Ashley was an actual woman from Wales who started making Victorian-style head scarves, placemats, and tea towels from her home in the 1950s. Her crafts were so popular that she opened her first shop in 1960, and began to expand her business from there, specializing in linens, wallpapers, and, of course, dresses. Ashley was obsessed with old fabrics, old patterns, and old ways. In the 1970s, a Guardian retrospective declares, “Ashley’s dreamy designs offered an imagined memory of a safer past,” which “chimed well with a hippie impulse to reject city sophistication.”

The clothes had a “fresh country look” that Ashley, who grew up a Strict Baptist, believed “wouldn’t look good in a sleazy nightclub.” “If anything, the look has probably become more romantic over time,” Ashley said in 1977. Ashley loved to declare her hatred of gambling and vice, her love of the dawn and country life. She thought people of like-mind gravitated to her clothes and her brand, which, she believed, could make people more virtuous — “I think our product will help people have a calmer, more well-ordered existence,” she told Women’s Wear Daily. As for their workers, her husband told the Times that they employ “country workers” because “their values are not so distorted,” adding “we think the most successful way of life was before the Industrial Revolution.”

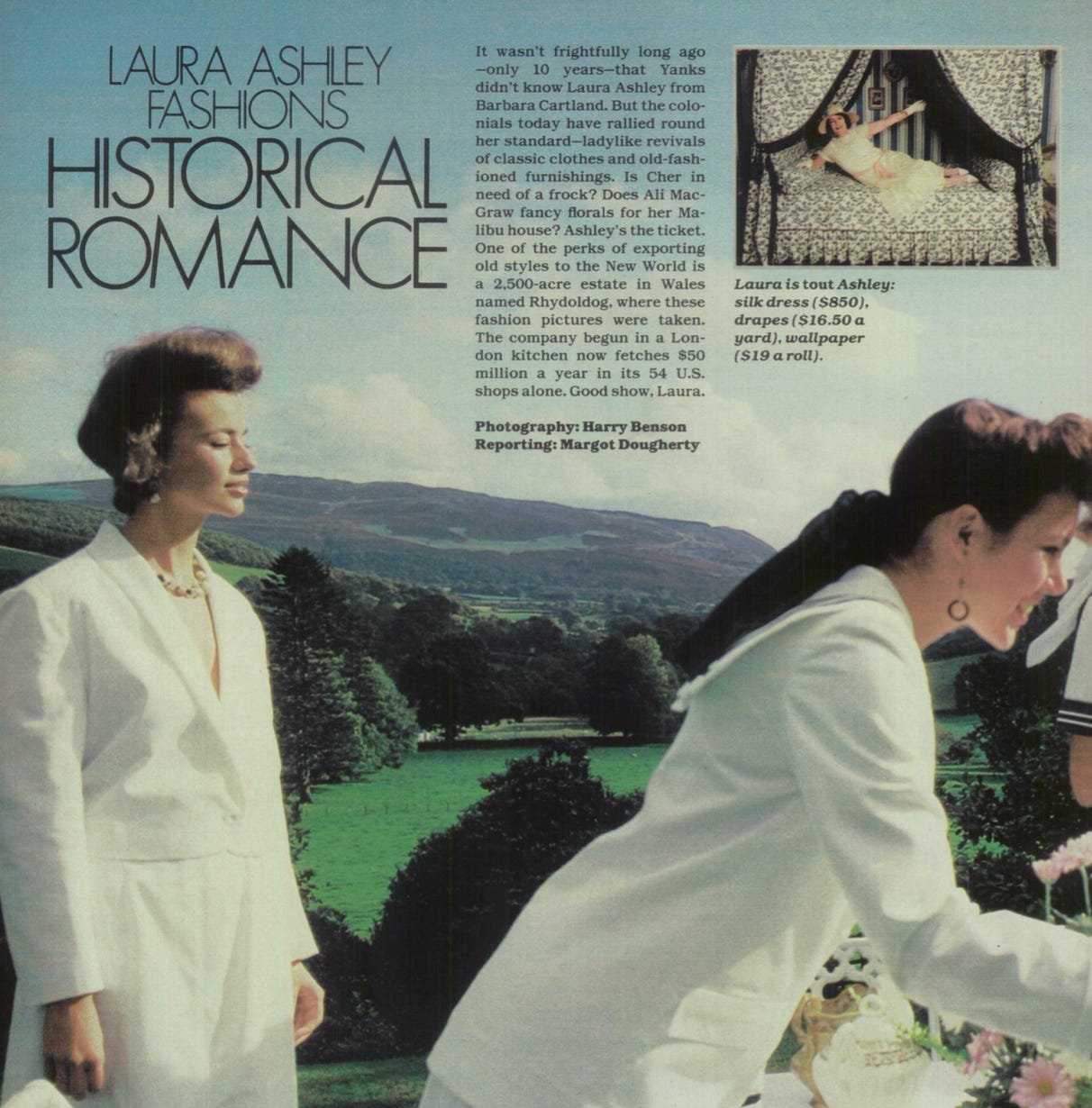

The first Laura Ashley opened in America in 1974, but it wasn’t until the early ‘80s that the brand came to feel ubiquitous — a signifier of refined British taste that was also accessible, if “luxurious,” to the masses of the middle class. At first, sales at U.S. stores were slow — which surprised the company, since their UK stores were always packed with American customers. Then they realized it wasn’t the fabrics or designs themselves that allured American customers so much as the overarching aura.

They transformed all stores to look like they were straight out of Victorian England, with “quaint wooden storefronts, narrow interiors crowded with antiques and period knickknacks.” The salesgirls all wore period-evocative clothing. “By wrapping our customers here in a total Laura Ashley environment, it was easier for them to understand our design concept,” the president of U.S. operations told Newsweek in 1984. “It also gave us more of a feeling of being a designer product, which Americans like.”

To further the designer push, they marked up the items. In the UK, a Laura Ashley skirt would cost $18 in 1984 dollars. ($46 in 2021 dollars). In the US, they’d sell the same skirt for three times as much. Stores were placed alongside similarly aspirational brands (Gucci, Mark Cross) and if they had to be in a mall, it was always the fancy one with the Saks Fifth Avenue. The company already had free marketing in the form of Princess Diana, the “people’s princess” whose wardrobe regularly featured Ashley items. But they also eschewed traditional advertising, which could easily come off as garish, in favor of word of mouth, expansive spreads in Life, and glossy home-furnishing catalogs that sold in bookstores for $4 ($10 in 2021 dollars). In 1984, the company sold a staggering 2.3 million copies of their catalog — enough to put it on best seller lists at B. Dalton and Waldenbooks.

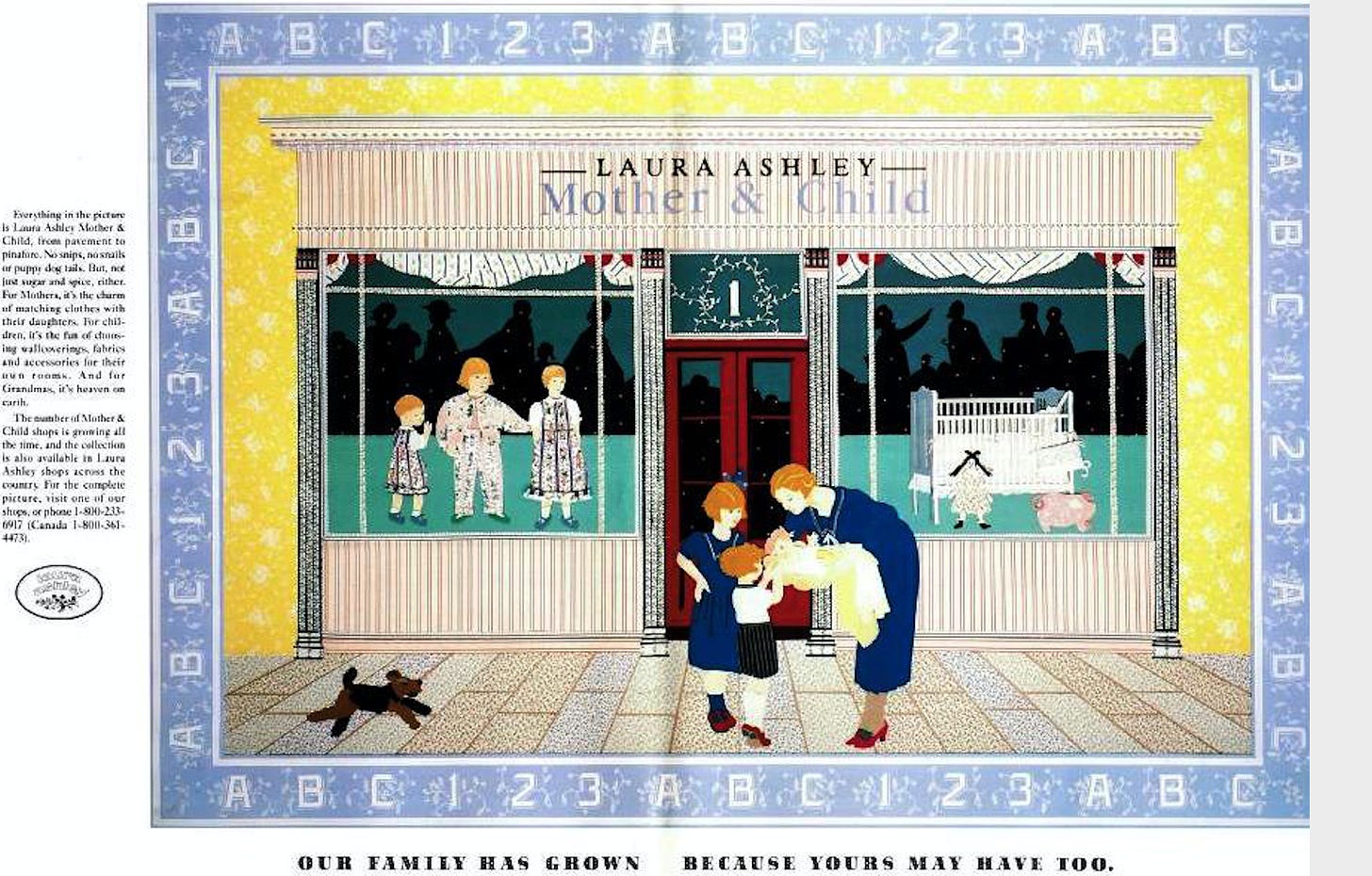

In 1983, Women’s Wear Daily featured Laura Ashley’s Bloomsday collection, “inspired by the genteel England of Virginia Woolf’s time.” Nestled within the spread was a brief mention of a “departure” from their usual product: a line of children’s dresses. Over the next decade, these dresses would become a centerpiece of the American iteration of the brand, anchored by the opening of dozens of “Laura Ashley Mother & Child” boutiques, often within existing Laura Ashley stores.

If you have a memory of a matching Laura Ashley dress — matching with your sister, your mother, your cousin, your grandmother, a fellow flower girl or bridesmaid — it’s from around this ten year period, from 1983 to around 1993. They were prized Bat and Bar Mitzvah dresses, what the fanciest girls wore to Sunday School, the stuff of family photos and Easter photos and High Holidays celebrations. If you couldn’t afford the actual Laura Ashley dresses, there were dozens of Laura Ashley-branded patterns for purchase — and knock-offs galore. (I wore a Laura Ashley knock-off to my Uncle’s wedding, at that point the fanciest occasion I’d ever attended, circa 1990).

In hindsight, Laura Ashley was most ‘fashionable’ around 1983 and 1984, but reached full United States market saturation in the early ‘90s — which is also when the brand itself began to struggle. The UK recession put a massive dent in its overall profits, and the overall image began to seem out of step. In 1991, it shifted its UK marketing towards the “working woman” who, research found, was their typical customer, and slightly adapted the look of the brand. In a 1993 interview with Marketing, then-CEO Lesley Exley described the brand’s key words as “romantic, feminine, naturalness, caring, environmentally aware (but more National Trust than Green), family oriented, cultured, well travelled and educated.”

You can always depend on an interview with trade magazine to turn subtext — the sort of thing a CEO would dance around in an interview with, say, Good Housekeeping — into text. All that’s left out is “white.” Buying a Laura Ashley dress wasn’t just buying a nice dress. It was associating yourself with a brand whose connotations were all of the above. Buying the same dress for your kid, and wearing matching dresses in public spaces (or for photography that would be displayed in your home) was like firmly wrapping your daughter in massive beach towel of class, of understandings of the family, of femininity, often echoed in the Laura Ashley decorations (or knock-off style) of the home.

“Not only are these outfits fun, but also one more way to signify to the world that essential bond between me and my daughter,” PE McNerney wrote in an article entitled “Two of a Kind” for the Hartford Courant, alongside a professional photo of her and her daughter in frontier style dresses from the Laura Ashley Mother and Child collection, purchased at the Westfarms Mall. (Which, according to a very swift response on Twitter, was most definitely the ‘fancy’ mall. In 2021 dollars, the daughter’s dress was $77 and the lace-edged pinafore was $53; the mother’s dress was $226 and slip was $120).

It’s no coincidence that the same years I yearned for a Laura Ashley-style dress, I also coveted a Samantha American Girl doll, and asked to decorate my room with a white canopy bed draped in pastel pink and white. We lived in a small town in Idaho, and class delineations were, for me, still largely felt not spoken. But I understood fancy, and at that moment, in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, middle-class fancy meant unmistakably, overwhelmingly, traditionally feminine.

The old-fashioned, unapologetic white femininity of Laura Ashley operated in concert with the postfeminism of films like Pretty Woman, released in 1990, which offered a permission structure for women to stop fretting about equality, and sexism, and the patriarchy — and instead embrace the pleasures of shopping, and domesticity, and fairytale endings. As Ashley herself put it, “The clothes are no women’s lib. They’ve always been highly romantic, because I’m highly romantic.”

Just as Ashley fever initially spiked in 1983 and 1984 — arguably the height of Reaganist, pro-American fervor — the popularity of the Mother-and-Child collection coincided with the first Gulf War. As in the late ‘30s and late ‘40s, the visual cohesiveness of the middle class family, coupled with the reipscription of traditional gender roles, helped communicate a cohesive story about post-Cold War American identity to make the narrative of the Gulf War, and the U.S.’s role in it, even more legible. Was it patriotic to wear matching Laura Ashley dresses? Not exactly. But in that moment, it sure was American.

The Laura Ashley dress was gradually subsumed by the cheery, pop styles of the late ‘90s, with the Spice Girls and Britney Spears offering a new, midriff-baring feminine ideal. When 9/11 hit, the dresses were still firmly in the out-moded bin, still too recently popular for real nostalgia. Boho styles — a sort of rebellious cousin to Laura Ashley — would reemerge in the mid-2010s, this time in the ‘festival chic,’ Free People styles of a 16-year-old’s first trip to Coachella. The look is ‘romantic,’ but also meant for people with Pretty Little Liars hair and bikini tops with tassels.

But a more conservative version was percolating as well. Christy Dawn, whose price points, hem lines, and small florals fabrics make the dresses ringers for Laura Ashley, launched in 2014. The company makes “sustainable, ethical, and timeless” dresses that are “vintage inspired” with the latest collection dubbed “Farm to Closet.” Laura Ashley was obsessed with reviving old prints and patterns; Christy Dawn has made its reliance on dead stock a central selling point of the brand. Laura Ashley relied on word of mouth and catalog direct-to-consumer marketing; Christy Dawn relies on Instagram influencers and targeted social media ads (which is how I first found the brand).

Laura Ashley’s marketing was almost exclusively white and slender; Christy Dawn has made racial diversity and (relative) diversity of size central to its brand image. Some women complained that Laura Ashley’s designs made them look pregnant (Ashley’s response: “Ah, but what’s nicer than being pregnant?”); Christy Dawn has “curated a collection of loose and flowing fits with baby bumps and nursing in mind.” Laura Ashley and its Mother and Child collection, and Christy Dawn has “dreamy deadstock creations” (aka matching dresses) “made for the little ones who light up our world,” photographed in the same scenarios of bucolic bliss.

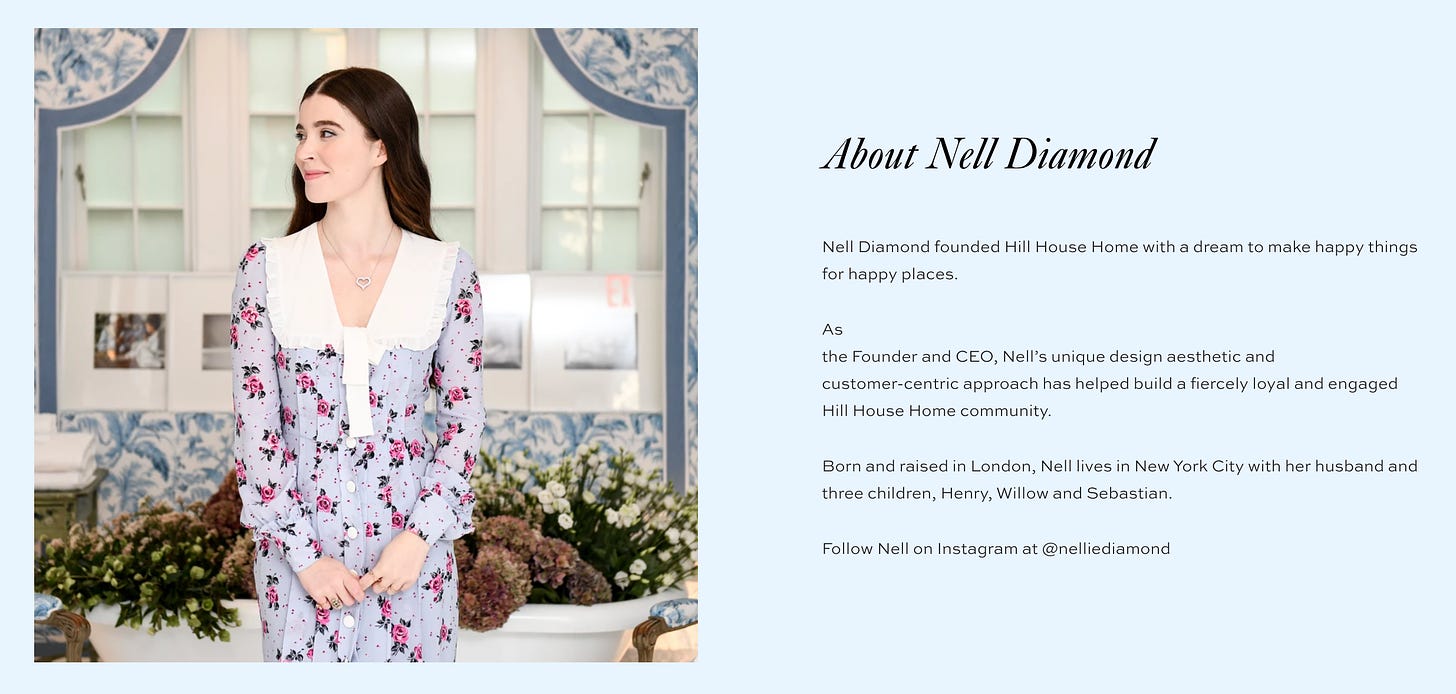

Other companies arrived at the Laura Ashley aesthetic by starting with children’s clothes and expanding into women’s dresses (Maisonette), or simply centering Laura Ashley mother-daughter styles as part of their Spring Line (the cover of Anthropologie’s Spring catalog). Hill House, the company responsible for the Nap Dress, launched as a direct-to-consumer bedding company in 2016, competing with Bowl & Branch and Brooklinen, before expanding to home, accessories, bridal, and apparel for kids and adults, with the stated goal of designing “product that bring beauty and joy to everyday rituals.”

On the Hill House website, the portrait of the founder and CEO, Nell Diamond, could be straight out of a Laura Ashley promotional shoot. Her goal with the company: “make happy things for happy places,” e.g., the home. That includes the nap dress, launched in 2019, which Diamond explains as “an extension of my identity as an extreme homebody.” “I would spend all my time at home if I could,” she told Fast Company. “But I also want my outfit to make me look polished and at my best. I don’t think you need to compromise on that.”

After COVID hit, the nap dress became ubiquitous, even as overall clothes sales dropped 79% in the United States. It was all over Instagram. It just looked comfortable — and like something you wouldn’t feel totally weird about buying and wearing around the house, expensive enough to feel quality but not prohibitively so. This Spring, the company sold $1 million worth of dresses in 30 minutes after the launch of its new line, and the company’s overall revenue is projected to increase 300%. This summer, they, too, have doubled down on Mother-and-Me matching sets — a way to encourage its typical customer, who already owns three nap dresses, to buy another iteration.

The Nap Dress itself overflows with meaning. It’s less Victorian, more Regency — a play on the house dress of Bridgerton and Jane Austen. The evocation of the nap summons the idea of leisure and restfulness, if not the actuality (Diamond points out that the dress’s name is a ‘misnomer’ and you’re not actually meant to nap in it). It looks like it could be homemade but, because of its Instagram ubiquity, signifies as a higher-end brand. It buttresses the belief that traditional femininity is “simple.” (A friend showed up to a gathering in one the other day and all of the women immediately came up to say “I like your nap dress!”)

The Nap Dress, like all products targeted at women intended to provide leisure, also doubles as a work dress — adaptable to childcare (the ruched top works for nursing; the length makes it easy to chase kids without flashing anyone), domestic chores, or appropriating the costume of feminine formality for a quick work Zoom call. You can wear a bra with it or, you know, maybe not. You could argue that it’s the evolution of the Lululemon yoga pant: the uniform of the bourgeois mom who does it all, or at least attempts to do it all, only now the visual reminders of the vigilance required for body maintenance (exercise clothes all the time) are subsumed by a ballooning skirt.

The online cottage core aesthetic has been described as a “Holly Hobbie illustration come to life, consisting of a coterie of young people, mostly in their teens and early 20s, who congregate online to swap bread baking recipes and photos of their foraged mushroom hauls, stare at pictures of farm animals and otherwise partake in an aspirational form of nostalgia that praises the benefits of living a slow life in which nothing much happens at all.”

These Gen-Zers are nostalgic for a screen-less past, but they’re also yearning for a world, and life, less defined by productivity and work ethic. If millennials are, according to one particularly perceptive Gen-Zer, “obsessed with job security” and “moaning” about the ways they’ve been fucked over, Gen-Zers say fuck it, we’ll create an aesthetic alternative. As one cottage core enthusiast told the New York Times, “cottagecore is all about finally feeling comfortable and at peace, even if that peace is fake.”

The Nap Dress — and the greater popularity of the Laura Ashley aesthetic — is doing something slightly different. Whereas the performance of cottagecore is, at least in part, about finding community with like-minded others apart from the home, the Nap Dress, and mommy-and-me dresses more broadly, look inward. The primary connection is the familial one; the kid’s dresses effectively create an echo of the self, even when one’s understanding of what that self is (Am I mom? An employee? A wife? A respected member of society? Of worth? What do I actually value?) becomes unstable. They don’t say fuck it. They say maybe this will finally make it work. Millennials, after all, don’t give up. They try harder.

Even if you’re not a mom, or don’t wear matching dresses, wearing one is a shortcut to legible class and gender performance. As Laura Ashley’s husband told Life in 1984, “Laura’s clothes are the way a woman should look.” If you’re feeling unmoored post-pandemic, one of these dresses tells you — and others — who you are.

I like some of these dresses, and my style admittedly leans towards ruffles and lace. But I can also see what the aesthetic, like Laura Ashley before, longs to communicate, to smooth over, to remember and forget. Many of these companies are more sustainable, with far more diverse marketing, and far fewer imperial undertones. But they’re still nostalgic for a past that was repressive and miserable for most, obsessed with the control of both empire and women’s bodies, bolstered by myths of the beatific mother and feminine duty and purity.

They’re beautiful, these dresses. But they’re also an echo of an echo of a song so familiar we’ve ceased to hear its sadness.

If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version. One of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week. Tomorrow the thread will be crowd-sourcing questions for our Culture Study finance columnist, who’s going focus on financial advice for people who have student debt, are scared of their retirement plans or lack thereof, or just generally feel excluded from most financial advice. Come!

The other perk: Sidechannel. Read more about it here. It has truly become one of my favorite places on the internet. The newly added private job-hunting channel is pretty great.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

"In 1983, Women’s Wear Daily featured Laura Ashley’s Bloomsday collection, 'inspired by the genteel England of Virginia Woolf’s time.'"

I, er. Had Women's Wear Daily ever read any Virginia Woolf? And had Laura Ashley's designers read any Joyce? Because I don't think that statement of brand identity is saying what they thought it was saying.

"The Nap Dress, like all products targeted at women intended to provide leisure, also doubles as a work dress — adaptable to childcare (the ruched top works for nursing; the length makes it easy to chase kids without flashing anyone), domestic chores, or appropriating the costume of feminine formality for a quick work Zoom call. You can wear a bra with it or, you know, maybe not."

But does it have pockets????? I bet it doesn't! Which means, like all women's clothing, it isn't *actually* practical or useful as a "work dress" if you don't have a place to put your phone, a binkie, a kleenex, etc. I've taken to wearing a fanny pack when doing chores/errands because none of my "work" clothes (athleisure, mostly) have useful pockets. I hate it!

*hops off soapbox*