What sort of art makes your experience of the internet bearable? Whose presence in your inbox reminds you that inboxes used to be sources of delight? Whose words feel like buoys? Some of you have told me that Culture Study sometimes does that for you, which is incredibly kind of you and makes all of this feel worth doing. But today I want to tell you about the person who does that for me.

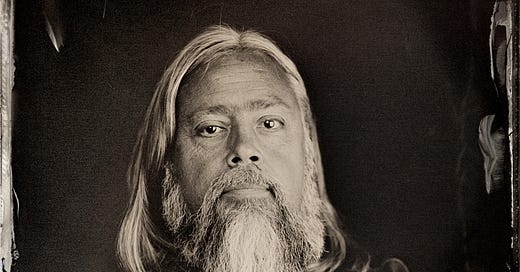

His name is Chris La Tray, and he writes the newsletter An Irritable Métis. Sometimes it’s waiting for me when I wake up, and reading it knocks me into a much better headspace to greet the day. (This piece did that for me earlier this week). Sometimes it allows me to access some of my anger, or forces me to sit with a contradiction. There’s an honesty, a rage, and a tenderness there that leaves me awestruck.

Chris was one of the first interviews for this newsletter, and back then, we talked about finishing up the draft of his forthcoming book, Becoming Little Shell. Here’s how it described it then:

It is roughly about my family and our relationship to the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, which I am an enrolled member of. We just got federal recognition almost exactly a year ago, after 156 years of being denied by the US government.

What I’m trying to do with the book is tell the larger story of who we are — call us the Landless Indians of Montana, the Montana Chippewa, the Chippewa-Cree, or, as I prefer, the Métis — because we have largely been erased from history and we have been in this area since at least the 1730s, and probably longer. The narrative thread is my dad’s side of the family; my dad, and his dad, denied their Native heritage for many reasons. My book explores those reasons — at least what I think they are — and why they’re common with so many Native people of those generations ... and then the effect they have on people like me.

This exploration of what happened to us, and how it is being reflected in events happening in the world today, has entirely changed my view of the world … down to how I look at what I see out my window. It has also served to radicalize my political views from “Oh, wouldn’t that be nice,” to “Let’s fucking do this!” It’s made me angry and joyful, hopeless and bursting with love, all at the same time. It’s exhausting, frankly.

Today, Chris and I are talking more about the book, and what’s (not) irritating him lately, and the Cooper’s hawk out his window, and his favorite gas station, and nothing and everything in particular. I hope you’ll see some of what makes his work so precious to me, and consider subscribing to his newsletter here.

Last year, I asked what was irritating you lately — and you wrote that “it seems our collective courage is flagging and there is no time for that.” I think irritations endure and diminish, gain texture and anger. So what’s changed about this particular irritation? I personally find myself constantly oscillating between great hope and crushing discouragement at just how resistant our systems are to change.

I couldn’t write under the banner of “An Irritable Métis” if I weren’t in a relentless state of irritation at some level, could I? So that is a constant, for myriad reasons, most of which are irrational and foolish.

But I am like you in the oscillation and it’s really hard. It’s like whack-a-mole. For every problem smashed a couple pop up elsewhere, which isn’t optimal for someone like me who doesn’t really lean on hope as anything more than a copout for folks who just want to throw their hands up and do nothing to “be the change” their bumper stickers exhort us to be.

But I do see glimmers in strange places. Take my tribe, the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians. We got federal recognition right before COVID. Our last gathering was in January of 2020. All of our public meetings, powwows, etc. have been canceled since. We carry a history of executive dysfunction, frankly, both internally and in our dealings with the world at large, which is understandable given the prodigious efforts made to eradicate us. And yet, when the CARES Act dropped $25M in our bank account in June of 2020, and initially a deadline of December 31st to “use it or lose it,” we made shit happen and really initiated a lot, A LOT, of positive change that will benefit the majority of our tribe.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t bumps that frustrate me, like members from other states griping, “I live in Idaho, why should I care about a health clinic in Great Falls?!” But that’s how society works. The needs of the many vs. the needs of the few and all that, and a lot of people are dicks to boot. We have done some great stuff and there is more coming, despite the irritations, so I figure if we can do it, anyone can. It just happens slower than we want it to most of the time.

I’ve been reading Angela Garbes’ forthcoming book Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change. She spends a significant chunk of time thinking through the ways in which colonization has devalued and otherwise made impossible Indigenous models of care and childrearing, and how white colonial tradition privileges a nuclear model of caregiving that is so incredibly easy to bust wide open. Garbes focuses on the Filipino context, but I’m wondering if/how this sparks any connections with your forthcoming book and Métis models of community and care.

That is a great question and I wish you’d asked it when I was still writing my book, heh. The truth is that for Indigenous people, schools were a weapon used against us, to destroy us, to assimilate us (which is really the same thing), etc. We’ve all heard the stories of boarding school atrocities and I don’t know that I need to revisit those horrors, “kill the Indian, save the man” and all that bullshit. For more on that, I recommend Denise Lajimodiere's harrowing Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors; I sat with her on her back porch on the Turtle Mountain Chippewa reservation last fall and we shared some tears over Everything.

Even before the boarding schools, specific to my ancestors—the Métis people of the Red River Valley—schools were used by missionaries to exert authority over our growing population starting in the 1820s or so, but it took awhile. We were introducing Catholic ideas and folklore into our spiritual traditions long before the missionaries came. Catholicism arrived instead with the first traders and voyageurs in the mid-to-late 1700s and the missionaries didn’t show up until decades later. By then we were too strong for them to push around and Catholicism — a folk, “lived” Catholicism (in the words of Canadian scholar Émilie Pigeon) that was this unique and beautiful blend of Catholic and Indigenous spirituality — was well underway. So the black robes started chipping away and chipping away, more settlers arrived, and here we are. There was a time when everyone was fat and happy—the Métis were the preeminent buffalo hunters and traders of the day and for half-a-century or so arguably the strongest economic power of the region—but all one has to do now is look at a map and see who the winners and losers were. Schools, and a few million dead buffalo, all played a big part.

I do think a lot about how we educate kids since I’ve been teaching poetry these past couple years on the CSKT reservation north of where I live. You’ll have a white kid with a stable home, their own room, lots of toys and assorted 21st-century-American-kid shit going on in the same room as a Native kid whose mom is a drug addict, Dad is dead or in jail, one or both grandparents died from COVID, maybe eating once a day at school, living in an auntie’s little house with a bunch of other people. And vice versa! There are plenty of poor white kids in troubled situations on the rez, and not all Indians are destitute. Either way it’s heartbreaking. Yet when either kid acts up, I’m talking the comfortable kids vs. the troubled kids, the teacher attends to that acting up the same. How can they not? Teachers are overwhelmed too! But these kids are not the same, their needs are entirely different. Exclusive to reservations? No, and that’s the shitty part. I don’t have answers to it either, just heartache.

This pandemic has really exposed all the gaping holes in our system of caring for each other, holes that the people on the ground have been complaining of for years. It’s complete and total societal breakdown. The frustration is the resources exist to fix it, we just choose not to use them.

You and I both loved Lyz Lenz’s piece on Midwestern Gas Station culture from last month. Can you tell me about a c-store that lives in your heart? Why does it matter, commemorating these unsung yet essential corners of our lives?

Until I moved where I live now there was always a convenience store nearby that I frequented. I suppose even here, there was one initially: Frenchie’s Conoco, six miles west in Frenchtown. When I stopped drinking soda that killed consistent visits, and Frenchtown is a landfill of COVID-denying toughguys anyway so now I avoid it completely. But if there was a chain I was ever particularly loyal to it was the AM/PM stores in Western Washington when I was out there in the late ‘80s into the late ‘90s. There was one on my way to work I’d hit every morning, and then one close to where I worked that I would hit for lunch. It was glorious!

They matter, at least to me, because they become places where the lines between customer service and customer are blurred. I got to know people by name, etc. There is a community aspect to it in a unique way. Here is this person doing their shitty job, and I’m on the way to mine, or taking a break from it, and there is some solidarity there. At least there is if you aren’t a dick about the relationship. Funny how that concept comes up so often, isn’t it? Even in writing. I often get asked for advice for writers. “Don’t be a dick!” is the simplest, most important tidbit.

When I think about the stories that are going to stick with me after the pandemic, the story of you teaching poetry to elementary school kids, and that small precious sentence from their teacher in the comments. You’re still doing that, which takes a bit of wrenching of the heart every week, and you’re dedicating a lot more time to the newsletter. Are you like me, in that it feels like catharsis to get this stuff out, on the page, in the world? Or does this vulnerability take an emotional toll? I guess this is another way of me asking: the open-heartedness, is it sustainable? Does the blood run dry?

I think I’ve sat and stared out the window reflecting on this question more than any of the others. I was recently asked if there is catharsis in this writing and I said no … but maybe there is. There is something deeper about it, certainly. Yet without sounding grandiose or melodramatic (or, god forbid, white lighty), I’m also a person who believes that the universe presents us with opportunities to guide us and I have certainly been the beneficiary of that and I’ve tried to heed these nudges from my ancestors. This has certainly been the case with my Little Shell book, and how what I thought was this small story about a little family and an unknown tribe became so much bigger.

Now I find myself with a much larger audience (though still tiny, in the grand scheme of things) and to not really bloviate about all these things I care so deeply about seems a waste. The late writer Charles Bowden talks about giving up teaching to devote himself to what matters to him as a writer in this wonderful interview with Scott Carrier. He says, “Look, you have a gift, life is precious. Eventually you die, and all you’re going to have to show for it is your work.”

He also says, “It’s easy to make a living telling the people in control they’re right,” a sentiment I swiped for a newsletter of my own last year, which also happens to be one of my favorite posts. It kinda answers this question in some ways. Amusingly enough, looking at it again just now, it also references our first interview together. What a coincidence! SEE WHAT I MEAN ABOUT THE UNIVERSE!

Annie, we absolutely must remain open-hearted, and pray our time runs out before our will does, and that we have people queued up behind us to carry our efforts forward. There is a long list of folks I was queued up behind without even knowing it and here I am. At the same time, even if I did retreat from the world, from knowing all the shittiness of it, where would I go? If I’m in a cabin in the woods I’m still surrounded by relatives and all the ensuing drama, they just aren’t human. I can’t turn off being open-hearted about that either.

No bullshit here: this morning, typing a few words, reflecting, typing some more, all of a sudden the birds outside my window scattered. A Cooper’s hawk was among them and killed a sparrow. She held it in the scraggly tree a moment, separated from me by maybe half-a-dozen feet and a pane of glass, then flew off with her meal. I keep a camera at my desk and managed a few stills. On the one hand I feel sorrow for the hunted, but exultation over being able to witness the hunt. Now there is a light snow falling against the gray of the horizon and no birds are there and I am left reflecting on all this stuff, this literal life and death stuff that we are all engaged in every moment of our lives.

Sustainable or not, what joy it is to be open-hearted, with all its misery. What devastation not to be.

Tell me some writers whose work is buoying you right now.

Something I’m sure you can relate to here, but given how much research reading I’ve done over the last couple years, as much as I love knowing what I now know it has been emotionally difficult and has somewhat transformed how I read and the pleasure just isn’t the same. I’m trying to reclaim that but still struggle against what I “should” (what an unfortunate word) be reading versus what I want to read. It’s a kind of paralysis.

I never fail to find succor with the old Japanese and Chinese poets who wrote the same kinds of things I did, though. This little essay about Issa, written by my friend Leath Tonino, perfectly sums up why.

Speaking of Issa. I referenced him in this bit from an essay I wrote last year for a reading I was invited to give in celebration of Missoula’s magnificent new library, the grand opening of which, I asserted, given the nature of our times, was nothing less than a subversive act. It’s relevant to our discussion so I’ll close with it. Issa wrote his most famous poem in 1816, just after the death of his young daughter, who was not even the first of his children to die. He writes:

The world of dew

Is a world of dew, and yet

And yet....

And yet ... what? This world of dew dries out on the brittle grass of our scorched landscape just after the arrival of the sun. And yet, the sunrise is still beautiful, is it not? And yet, the laughter of children is still uplifting, is it not? There is yet love in the world, isn't there, however subversive? Wine to drink, heart's-desires to drink it with? Let us feel our grief, but let us remember our ancestors before us and those yet to come and be bold in our subversiveness! Rejoice that we are here together.

Rejoice indeed. Thank you for the invitation, AHP. I rejoice in sharing this world with you, in all its magnificence and awfulness.

You can subscribe to Chris’s newsletter here — he doesn’t promote the paid subscription option much, but I love monetarily supporting the work & maybe you would too). You can also buy his exquisite book One-Sentence Journal here (Bookshop) or here (Fact and Fiction Bookstore in Missoula).

If you value this work — and meeting people like Chris! — consider subscribing:

Subscribing is how you’ll gain access to the weekly Things I Read & Loved, but it’s also the way to participate in the heart of the Culture Study Community. There’s the weirdly fun/interesting/generative weekly discussion threads (this week’s Tuesday Thread on PERFECT ALBUMS was a true delight) plus the Culture Study Discord, where there’s dedicated space for the discussion of this piece (and a whole thread dedicated to Word games), plus equally excellent threads for Career Malaise, Productivity Culture, Home Cooking, Summer Camp Blues (for people dealing with the bullshit of kids summer camp scheduling), Spinsters, Fat Space, WTF is Crypto, Diet Culture Discourse, Good TikToks, and a lot more.

If you’ve never been part of a Discord: I promise it’s much easier and less intimidating than you imagine. Finally, you’ll also receive free access to audio version of the newsletter via Curio.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I love and cherish that man's words so much.

The art on the internet that makes it bearable?

Chris's writing, Samantha Irby's newsletter, The Dogist, Useless Farm and Failing Full Circle on Tiktok. When it's a bad brain day, all those are guaranteed to make me feel better about something.