When Music is Torture

Talking musical control, discipline, and context with musicologist Lily E. Hirsch

AHP note: This is the (only slightly delayed) September Edition of the Culture Study Guest Interview series. I interview people nearly every week for this newsletter, but my inclinations and passions are, well, my own. If you have a pitch for an interview with someone who is not famous but writes or does work on something that’s really interesting, send it to me at annehelenpetersen @ gmail dot com. Pitches should include why you want to interview the person, 4-5 potential questions, the degree of certainty that you could get the subject to agree to the interview, and have CULTURE STUDY GUEST INTERVIEW in the subject line. Pay is $500. This month’s interview is conducted by Maggie Wang, who you can learn more about at the end of the piece.

When she taught at Cleveland State University, the musicologist Lily E. Hirsch remembers that the university library had a peculiar end-of-day ritual. At closing time, the library would play music to get its visitors to leave. It was usually something calming, Hirsch says, often classical music. But in a library, where silence is sacrosanct, even a subtle musical presence can dramatically change how you experience the space.

The idea that music can be used to control territory and influence behavior is at the heart of Hirsch’s 2012 book, Music in American Crime Prevention and Punishment. She demonstrates how music has been used—by police, prosecutors, and judges as well as by businesses and ordinary people—to shape American notions of what is “right” and who “belongs” where.

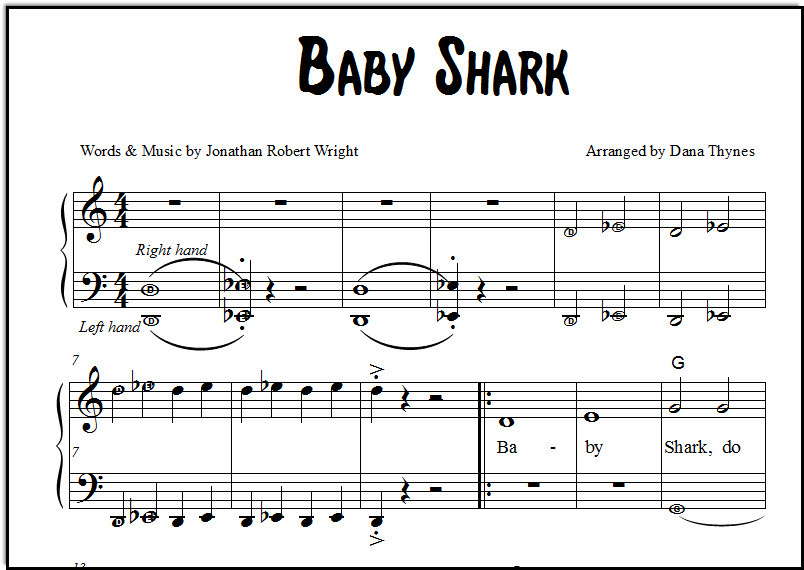

In the decade since the book came out, music and the law keep popping up in Hirsch’s work. A few years ago, the city of West Palm Beach, FL made headlines for blasting the children’s tune “Baby Shark” to discourage unhoused people from sleeping in parks. In the aftermath, Hirsch received emails from journalists around the country asking about the history of music as a tool for spatial control. People are still surprised that music can be used in negative ways: they think music is supposed to be sublime and uplifting, Hirsch says, but music can just as easily be destructive. That destructiveness is not something to cover up or shy away from. It’s part of the power of music.

Hirsch is an amazingly curious scholar. Since 2012, she’s written a book on the Jewish musicologist Anneliese Landau and another on the singer “Weird Al” Yankovic. At the moment, she’s working on three more projects: one on the toxic labeling of women in music, another on insults in and about music, and a third on humorous music. It’s clear from our conversation that Hirsch is dedicated to making music—and music appreciation—more accessible and interdisciplinary on all fronts.

A few days after I interviewed Hirsch, I went out for lunch with a friend. We sat at a table on the sidewalk, only to find our conversation interrupted by a car blasting music from a set of giant speakers in its trunk. The music itself was fine—I might’ve liked it in some other time and place—but I thought back knowingly to Hirsch’s comment about what happens when you don’t have control over what you’re listening to. Later that afternoon, I stopped by a secondhand bookshop. The first thing I noticed when I opened the door was the music: it was eerie, somewhere in the realm of symphonic metal, and unlike anything I’d ever heard in a bookstore before. I went home with a copy of Stephen Spender’s autobiographical novel The Temple. I wondered how the music had shaped my choice.

And now, here’s my interview with Hirsch — which has been lightly edited for content and clarity.

How did you become interested in the relationship between music and the law?

It started off with a simple article. I had just finished my dissertation dealing with the topic of Jewish music, specifically the negotiations around music during the Nazi era. I was thinking about new projects, and I saw an article about the use of Barry Manilow in Australia to repel loitering. I found that fascinating. I looked into the history of it, and I wrote a paper and presented it at a musicological meeting. It was such a different topic for me that I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing.

Then I started to think about what other connections there might be between music and crime prevention, and between music and the law. I wanted to do something that didn’t have to do with copyright law, because I had read a lot about that. As I started digging, I saw connections with victim impact statements—if music is included in victim impact statements, does that somehow bias the court or create an unfair advantage? I saw the use of music, specifically rap, as evidence for crimes. I stretched it, too, to the use of music as torture, which I had just learned about around the same time.

I’m amazed how quickly the book came about, but I think it was partly because there was so much material. No one had done anything with it, and I had something I really wanted to say, which was that music is not used in solely positive ways.

Why does something still count as music if it’s not being used in a “positive” way?

In discussions about negative uses of music, people sometimes ask whether or not the music in question even is music. But those discussions distract from the real issue, which is how the music is being used and its effect on people. So, that whole discussion is self-serving. It’s related to people’s notions of what music should be, and whenever you use those “shoulds,” you’re not looking at what music really is, and you’re avoiding the real issue that should be up for discussion.

I’m certainly thinking here of musical torture. Music has been used as torture in a lot of different contexts, including in the American so-called War on Terror. The discussion came up among music scholars of whether music used as torture even is music. Can music actually be torture? At first, I was caught up in the discussion, but immediately I started to think, This is not the point. The torture is the point. What this is doing to people is the point, not whether or not it’s music.

How exactly has music been used as torture?

Sometimes it’s for sleep deprivation — loud music keeping someone awake. The body breaks down from lack of sleep. But there are symbolic uses too, where the music of a woman might be used to torture a man of particular Muslim faith where there are prescriptions around music and the music of women. We saw that also in Nazi Germany, where a song by Wagner was used in the concentration camps to harass prisoners.

Particularly catchy music has also been used. One example from the War on Terror is Barney’s “I Love You.” It’s very repetitive: an earworm that begins to fire on repeat. People talk about it as funny, but it can interrupt thought and interrupt a person’s connection with the self, which is already under threat when you’re under someone else’s control. That emotional impact, that interruption of thought, can be just as destructive as a physical response like loud music hurting the eardrum and interrupting sleep.

Should the history of music as torture change our relationship with music at all?

It’s a good reminder that music can be used in a lot of different ways. Because I’ve written about these topics, I have been asked, “Do you even like music?” I find that question wild, because I would think, if you do care about music, if you do love music, you want to know all that it can do. You want to know it in full. And part of knowing it in full is recognizing all these different ways it’s used.

Where and when does the earliest documentation of music as a crime deterrent come from?

I’ve never tried to pinpoint the very beginnings of this besides the use of music to repel teenagers from storefronts and other public places, which seems like something a few people thought of in different ways. You even see it in movies where the hero wins by playing music and scaring someone off. But I did find the 7-Eleven to be one of the earliest institutions that came up with the idea of using music played outside to repel “loiterers”—teenagers, homeless people, anyone they deemed undesirable—and that dated back to, I think, 1985.

Has music been used in positive ways as an instrument of the law? Maybe to offset these negative uses?

There’s this idea that music can be a moralizing force or a source of education, and maybe that’s what was happening with regards to crime deterrence. The music wasn’t chasing people away and reducing crime. People were somehow becoming better people and not engaging in criminal acts. I thought that was a very disingenuous idea, since music was not, in fact, working that way. It was really marking territory based on associations, kind of like a bird call with baggage.

Can you talk more about music as a marker of territory? How exactly can sound delineate space?

There’s an idea called CPTED, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, which says that there’s a way to “fix” your environment through environmental design. You can mark your territory through a wall or bushes or something like that, but playing music can also mark space through what you hear: “This is my area. You’re hearing my music. This is not your music.” If the music goes away, that changes your environment. That changes what’s considered “your space”.

There is space in music itself too. I used to tell music appreciation classes when I was playing Copeland, “Hear the wide-open space with these big octaves and all of this openness and vastness.” So, music can change your experience of space in a general way, but also in specific ways through environmental design, what you’re playing and where, who’s hearing it, and who’s allowed to hear it.

How do we combat these negative uses of music as crime deterrent, torture instrument, territorial marker, etc.?

There was a court in Colorado that thought they could fight noise violators with their own sound. It was an “eye for an eye” type of idea where someone who was charged with playing their car radio too loudly could be sentenced to sit in court and listen to a playlist picked by the judge. But it wasn’t as simple as the judge thought, trying to impose one sound for another.

Let’s say you happen upon a town square, and there’s a certain type of music, especially classical music, being played. There might have been some discussion: “Let’s put in classical music to let young people know this is not their space” because of this older association with classical music. What could you do? Could you come in with a more inclusive music, and what might that be? I don’t know how you could harness music in that way and have it be seen as solely positive. Maybe there isn’t one solely positive way to use music. There are always going to be complications.

Is there any kind or genre of music that is fully inclusive, that isn’t exclusionary in some way?

Everyone’s going to have a different opinion based on their background, especially now, at least in the United States. It’s so polarized: if you play one sort of music, and the artist has made a certain political statement, there’s going to be someone who finds that music terrible. Is there anything that includes everyone right now with all the controversies around basic stuff like wearing masks?

We do have this idea that classical music is somehow untouchable, elevated stuff, but that’s not the case at all. Mozart was a bully, and his opera Don Giovanni in recent years has become a source of upset as advocating rape culture. I remember teaching that opera in music appreciation classes and putting on the Catalogue Aria, which is sung by Leporello, Don Giovanni’s servant. Don Giovanni sleeps with everyone across Europe, and the aria is this song documenting his conquests. It’s supposed to be funny. I remember presenting it and feeling conflicted, but I knew this was part of the standard repertoire. This was in the music appreciation textbook. So, I just presented it and felt weird about it, because this opera is messed up — it’s glorifying a guy who “seduces” a woman —(it says “seduce,” but against her will). She’s ridiculed as this crazy, reappearing character, when she’s the one who’s been wronged. Mozart was clearly a jerk in some ways, but that’s all been washed away with that white wig you see in the movies.

How do you, personally, listen?

Being aware of these ways music is used helps. I have gut reactions to certain pieces of music because of their cultural associations. Sometimes you don’t even realize you’ve picked up certain associations, but it’s never just the music itself that’s doing anything. It’s all of this baggage, all of what our culture has created around it, that we’re responding to. And when you respond to a certain piece of music, it’s really important, I think, to go back a little and try to understand why.

I long said in the past—I don’t say it anymore—that I don’t like country music. Now I know there are amazing women in country music. I love Brandi Carlile. I’m a huge fan of some of these women. But in the past, I associated country music with white toxic masculinity, lyrics about trucks, and blind patriotism. Because of that association, I said, “I don’t like country music.” But music is rarely one thing, and genres are ever expanding and changing, and I have to step back and think about why I say the things I do or why I’m reacting to a certain piece of music in the way I am.

How does the experience of music “in the background” change the way we go about our lives? Does the use of music to mark territory affect us even if it’s not intended for us, per se? Or, put another way, is listening more than just listening?

Some of the best stuff I’ve read around this actually has to do with music in dining experiences, which I find fascinating: how music can actually affect the taste of food. But in your everyday environment, I think the context is important, the association with a specific music is important, and certain features of the music itself are important. You as an individual, your background, your earlier exposure to music, all of that is important.

I do see one overriding issue with music in everyday life, and that is the issue of control. There’s a great book by Martin Cloonan and Bruce Johnson where they talk about how, when you don’t have a choice when it comes to whatever that music is, it’s going to make a big difference. It’s the reverse of censorship, but it’s another form of control. You’re powerless against the music, and that takes away the enjoyment.

Music in dining experiences does sound fascinating. Can you talk more about that?

Isn’t that interesting? I haven’t dug that deeply into it, but I know there are theories about certain factors of music, even the difference between major and minor keys, affecting whether or not the food tastes sour or sweet. I believe the authors are David Hargreaves and Adrian North. Think about people trying to come up with playlists for their restaurants that are pleasing and how impossible that is because, again, of the issues of choice and control. Another finding with regard to restaurants is that lively or fast music could be good if you want turnover—if you want to get those people eating fast and to get them out of there. There are also studies showing that classical music can encourage diners to spend more at a restaurant or a store because you feel like you’re a part of this elite culture. Again, this is association, not necessarily the music itself.

Is that true of Wagner too?

Probably specific types of classical music are going to be more effective. If you’re piping in an antisemitic composer whom Hitler cited as his only predecessor, you are going to have some other issues.

You’ve written on such a wide range of subjects: Jewish music during the Nazi era, music in American crime and punishment, and “Weird Al” Yankovic. I know your next book is about women in music. What exactly are you focusing on?

When I finished my last book, which was on Weird Al, I was thinking a lot about language and the way we use words, because Weird Al plays a lot with language. I was just reading some light fiction, and Yoko Ono’s name kept coming up as an insult: “Don’t be a Yoko.” I started to think about that word and about how someone’s name can be turned into an insult. I started digging into that, and I found so many examples of that Yoko myth. At first, I wanted to do a book tracing that history: how this woman’s name became an insult and how unfair it is because, of course, she did not break up the Beatles.

This happens over and over, where certain words are used against women in music. There’s so much policing of behavior and enforcement of expectations about what women can and should be allowed to do. We all consume these messages, and it affects how we think we can behave. With the Yoko label, I remember being concerned about my behavior when I was dating a guy in a band. You know, you don’t want to be a Yoko. But how unfair is that?

We have a long history of dismissing women in music. As women entered the operatic stage, the term “diva” came about pretty quickly. Women, just by taking the stage as opera singers, were labeled as hypersexual and deviant. In the book, I talk about ideas of madness, which was connected to women going back to ancient Greece. “Madness” was viewed as connected to female anatomy and too much sexuality. You see that also in opera with the mad scene, a segment in an opera — for example, “Il dolce suono … Spargi d'amaro pianto” in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor — where a woman sings a real showstopper, very virtuosic, but she is going crazy and possibly dying, and that’s all entertainment.

I also remember reading about Britney Spears and the idea that she was “crazy,” and I wondered how many people were struggling and needed help but didn’t reach out because they didn’t want to be dismissed. Of course, it’s different for women than it is for men, especially in music: for men, if they’re mentally unstable, that’s a sign of genius. Karlheinz Stockhausen thought he came from the planet Sirius.

I was mad writing most of this book. It was so different from the Weird Al book, which I really enjoyed. For a lot of the Music in American Crime Prevention and Punishment book, I was disturbed. I was sometimes angry that a lot of these negative uses of music were disguised, but then I thought, okay, if I uncover this, then I can create change. I felt a sense of hope with that book. This book about women — the issues are out in the open. I want to create change, but I’m not always as optimistic as I’ve been with previous projects.

About the Interviewer: Maggie Wang is a J.D. candidate at Yale Law School. Her recent work appears in Harvard Review, Poetry Wales, and Inherited podcast. Her debut poetry pamphlet, The Sun on the Tip of a Snail's Shell, is out from Hazel Press.

I’m on the autism spectrum and react really, really strongly to music - I cannot listen to “background” music without reacting because it’s not in the background for me but in the foreground!

If I am in a restaurant or mall or anywhere music is playing, when I know the words I am unable to stop myself from singing and dancing. It’s extremely challenging for me to hold a conversation unless it’s about something related to the music or musician. (So, like, if a Mariah Carey song comes on, I can either only sing the song or start rambling to you about how in 2001 she was mocked for having a breakdown despite the fact that her ex-husband was actively sabotaging her career and stealing her material to give to Jennifer Lopez. Justice for her and Britney and all women who are screwed over by the patriarchal music industry!)

As a result, I am very upset by the increasing use of music everywhere in public spaces because it completely derails my brain to focus only on the music. I work in town/urban planning and cannot even escape it in my municipality - I was the only person on our downtown design team who didn’t want music on Main Street. Everyone else was like “if we play a top 40 mix (that excludes rap because racism) then everyone will stay and shop more!” And I was like “no…it’s too invasive and will stop people from being able to just relax and think while they shop” and no one else understood my point of view AT ALL! Meanwhile I’m over here trying to explain that I associate certain songs with certain chain stores and shopping malls due to their playlists and how I don’t want to do that with Main Street and I just get more weird looks. (And yes, that includes classical music. I sing along to classical music using the word “do”.)

So, all that to say…great interview! The topic of music and space really fascinates me as a music lover and someone in the urban planning field.

I live next to an extremely ritzy coastal area in LA. All the 7-11 stores started blasting classical music as the housing crisis got worse here. I love classical music and get mad about this for a lot of reasons, but the one that always sticks out to me is this idea that classical music is annoying and something to be used as punishment. This is a hugely interesting topic and I’m so glad this writer did this exploration.

Also on country music--I am a native Texan who worked in a country bar in college so I love the stuff, but get why people wouldn’t like it. I think Brandi C. has done a lot to make the genre more inclusive over the past several years.