I love hobbies. I love my own hobbies. I love that my partner is figuring out hobbies for the first time in his life after years of prime millennial optimization. And one of his hobbies is golf.

I used to play golf. My dad played and plays a whole lot of golf. I understand why people like golf. I also understand that part of its appeal — explicit or implicit — is just how much time it takes.

Eighteen holes of golf (in a foursome, on a moderately busy day) generally takes somewhere between four and five hours. If someone in your foursome is slow, or if the course itself is going slow for the day, that time can balloon further. Plus you’ve got to factor in time to get to the course (which, depending on where you live and traffic, might take anywhere from ten to ninety minutes), and warm-up, and add on any beer / food time at the end. So — at least six hours, if not more.

Sure, you can play a zippy 18 by yourself on a Tuesday morning. But that’s still three and a half hours — and unless you’ve invested the time to teach your kids to golf, you’re playing mentally and physically far from the responsibilities of home.

If you want to be decent at golf, you need to play about once a month. If you want to be better than decent and maybe just kind of good, up that to two, three, four times a month — plus fitting in time at the driving range. If you want a handicap under 10? More than that. Plus there’s the golf trips, which proliferate as they become tradition, and suddenly you find yourself a part of three, four, five annual and quasi-obligatory trips.

Golf is dominated by men — as of 2021, an estimated 75% of golfers are men, and the numbers are somewhat skewed by the high percentage of juniors and beginners who are women (37% and 36%). Some of that gender breakdown has to do with the visibility of male golfers, the historic exclusion of women from country clubs, all of the usual sexist sports stuff. But there’s another explanation, too.

A few weeks ago, when a friend and I were taking care of her kids and making dinner and waiting for our partners to come from a full Saturday at the course, I wondered: Is there any female-dominated hobby that takes as much time away from the home as golf?

The cheeky Twitter reply: golf. And yes, a woman could play golf and spend as much time as a man on her hobby. But what about other hobbies?

Marathon running. For your longest training run — which happens once, during months of training — you’re away for approximately the same time as one round of golf.

Cycling. I could see this argument — but it’s also not a female-dominated hobby. (The ratio of male-to-female cyclists is usually 2 to 1, if not more).

Skiing. Often but not always done as a family.

Competitive Horse Jumping. Okay yes.

Apart from competitive horse jumping, all of these activities are similar to golf: male-dominated hobbies in which women have (slowly) begun to participate.

So let’s think of some other male-dominated/male-coded hobbies:

Fishing

Hunting

Playing in sports leagues

Watching sports on television

Watching sports live

Cycling

Distance running

Woodworking / tinkering / carpentry

Car repair

And let’s think of some female-dominated/female-coded hobbies:

Gardening

Fiber arts (knitting, sewing, weaving, crocheting, quilting, etc etc)

Baking

Reading

Jewelry-making

Decorating/design

Organizing

Crafts, broadly conceived

The male-coded/dominated hobbies take place (with the exception of watching sports on television) away from the home, or in a scenario where child supervision would be unsafe (in a shop). They require significant, prolonged time commitments — up to a weekend, in the case of hunting or fishing. They do not perform a task that helps provide for the family (the exception here is if someone is making sweet furniture on the regular, or if they’re feeding their family with the game they shoot).

By contrast, the female-coded/dominated hobbies take place within the domestic sphere. Several contribute to or intersect with other “homemaking” domestic tasks. They are readily interrupted, and amenable to “episodic” engagement (kind of like a soap opera — you can keep leaving and coming back again; it might take a bit to get back into the swing of things, but it isn’t catastrophe). Crucially, you can dual-task while doing them — whether that means watching kids, or being around to take out the baked potatoes, or taking a break to switch the laundry. They blend with the rhythms of domestic life.

Obviously there are LOADS of exceptions to these gendered labels and I don’t think any of these tasks should be gendered but that’s how they remain — and it’s not difficult to see how they came to be that way. As modern civilization developed and expanded, women were (and largely remain) responsible for the private/domestic sphere, so they sought out leisure activities in the spaces to which they were tethered, and that allowed them to complete the infinite labor of the home. (If you were rich, other women were keeping house and caring for children, but you were still tethered to the home, so you could….read, play pianoforte, have your hair done, horseback ride on your estate).

Men were allowed and expected to circulate in the public sphere with other men; their leisure activities also developed in that sphere with other men. (Woodworking, metalworking, tinkering, etc. were less hobby and more trade — which took place in a discrete/separate area of the home or away from the home entirely).

I could make some Gladwellian determinist generalization here about how women have evolved, over several thousand years, to be “good” at the multi-tasking incumbent upon home-based leisure and men are “pre-disposed” to seek rest away from the home etc. etc. but I call bullshit: women have been socialized to understand interrupted, home-bound leisure forms as the general norm (with pointed exceptions), and men have, in turn, been socialized to understand uninterrupted, away-from-home leisure forms as the norm.

Again, there are exceptions here, and I applaud them, and they are beginning to ever-so-gradually unsettle the norm. But the norm remains — and even for people who disrupt it, ideas about what leisure should look like, how long it lasts, the sort of guilt that should be attached to it can darken the overall experience of leisure. Put simply, there are quantitative and qualitative differences in the way that men and women experience leisure — and there’s a whole lot of scholarly research and time use data to underline as much.

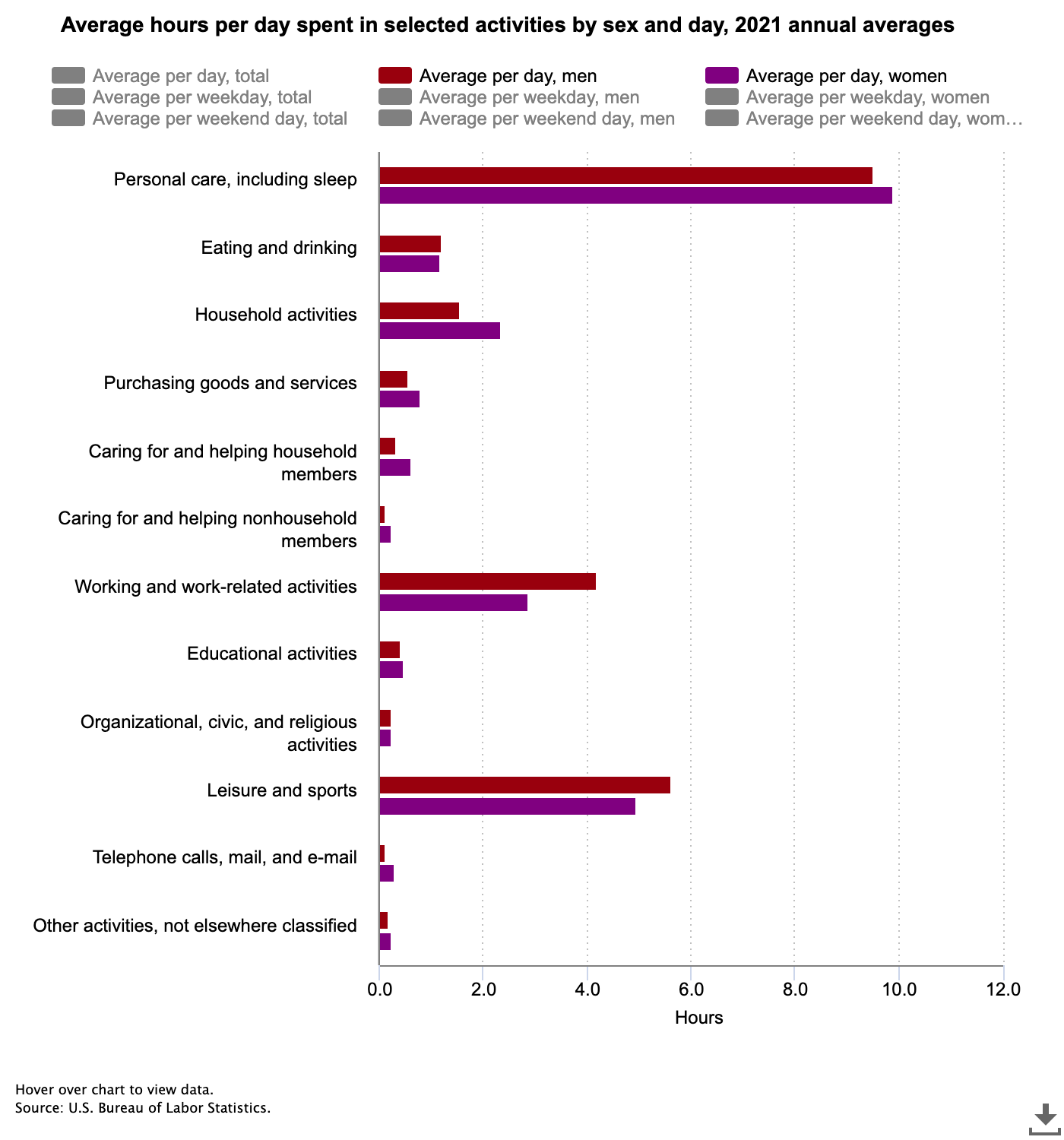

Here’s the latest data from the American Time Use Survey from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics:

Women spend more time on household activities, on “personal care,” on buying things, on caring for other household members AND non-household members, on educational activities, on telephone/mail/email — and significantly less time on “work” and leisure and sports. And if you parse the data by people with kids under 18 or not, it doesn’t necessarily improve (this data is admittedly a bit old, but you get it). In the UK, data from 2015 showed that men had an average of 43 hours of leisure time a week, compared to 38 hours for women.

So that’s the quantitative difference. But there are qualitative differences in leisure, too — women’s leisure is often “constrained,” aka, there is a driving pressure and/or guilt to get back to other responsibilities, which degrade the restorative and essential quality of the leisure. (Staring into space can provide the same restorative quality as, say, golfing; what matters, to bluntly paraphrase leisure scholars, is that you’re not constantly feeling like shit about the fact that you’re doing it, and/or a failure as a person or parent).

The literature review on this (accessible!) article from Community, Work, and Family provides a thorough summary of existing findings on gendered quality/quantity of leisure — especially appreciated these right to the point paragraphs:

[…] The ways in which women spend their available free time is seen to be of lower quality given the frequency of multitasking among women. Women’s leisure is more often bound up with family time. Mothers have less child-free leisure and are more likely than fathers to include children in their leisure activities, in essence ‘contaminating’ women’s leisure (Chatzitheochari & Arber, 2012; Craig & Mullan, 2013; Mattingly & Blanchi, 2003). Moreover, the time women spend in care activities ‘often spill[s] over into free time activities in ways that paid work hours do not’ (Nomaguchi & Bianchi, 2004). Another reason why women’s leisure quality is argued to be lower is that their family time and leisure time involve invisible efforts, such as the ‘coordination and planning, emotion and kind work, and the production of intimacy and sociability’ (DeVault, 2000). As mothers are more prone to take up these responsibilities, their leisure time may be more demanding and less relaxing than fathers’ leisure (Craig & Mullan, 2013; Nomaguchi & Bianchi, 2004).

Gender differences in leisure quality can also be a reflection of differences in individual norms between men and women. While mothers are less likely to have child-free leisure, when they do participate in leisure without children, modern ‘intensive mothering’ norms can generate feelings of guilt (Craig & Mullan, 2013; Mattingly & Blanchi, 2003; Nomaguchi & Bianchi, 2004). Scholars also suggest that women’s sense of responsibility for others prompts them to adjust their leisure to the needs and preferences of their partner and/or children (Miller & Brown, 2005; Shaw, 1994). As a result, their leisure activities are less in line with their own preferences and thus less enjoyable (Miller & Brown, 2005).

In summary: women’s leisure is bound-up in family time, it takes a lot of invisible labor to plan and thus can feel more exhausting than restorative, they feel guilty about taking it because a good mom is a present mom, they’re more likely to modify it to accommodate the needs of their partners/children and thus it’s often not what they actually really want to do. It is “contaminated” leisure.

I can readily think of this “contamination” in practice. The most obvious is the family vacation, or, as the classic Onion headline summarizes it, “Mom Spends Beach Vacation Assuming All Household Duties In Closer Proximity To Ocean,” but it’s also when women slot their hobbies (very very early in the morning, or very late as night, so as not to disrupt any other part of the family routine), or which hobbies wither and which survive simply because of the need to be able to perform childcare at the same time, or feel like your hobby is part of a larger greater good organizational schema (see: organization and decluttering as “hobby.”)

See also: scheduling weekends away to coordinate with child drop-offs and bedtimes; women who are the first contact on school forms so always the first to get called in the event of a small child-related crisis; women whose schedules are generally more flexible (either because their type of work for pay or because they don’t work for pay outside of the home) and thus are expected to bend their schedules, leisure or otherwise, towards everyone else’s needs; women who make less money (because of the persistent wage gap, because they took maternity leave, because many things) and thus feel they have less “right” to spend time or money on themselves; women who feel like time away from family should have a specific and finite and explainable purpose, instead of a vague and meandering one; women who have to find care for any time they want to do leisure outside the home, so why even bother.

Some of these needs also affect men’s leisure. No one’s saying that men’s leisure is wholly unconstrained. It’s just worth underlining that women’s leisure is significantly more constrained — and as a result, offers less of the life-balancing effects that it does, on average, for men.

The authors of the article on quality of leisure from above knew this. But they were also curious: how does this “contamination” factor change in countries where women share more of the load of care work with both men and the state (e.g., countries with mandatory use-it-or-lose-it paternity leave and widely accessible and affordable childcare). You can read more about their methodology in the piece, which was published in 2018, but they compared responses from 23 countries using survey data from more than 28,000 respondents in 2007 (a little old, but not ancient), and looked specifically at respondents’ feelings of “time pressure” on their leisure (a marker of quality) and how often they were able to use their free time to actually rest and recover (they also looked at parents/non-parents, age, education level, employment hours, and marriage status).

The authors found that in more “egalitarian” countries (like Norway) where care work is de-familiarized (e.g., shared with the state) the gender gap in quality leisure decreases; in countries without paternity leave, with more conservative gender norms, and with more childcare burdens, the gender gap increases. The differences are small, but clear. They also saw that as childcare responsibilities increased, leisure quality decreased — and that leisure “satisfaction” decreased for women when partnered, but not for men (wow).

All of this makes sense, but the authors are careful to point out that the quality leisure gender divide between, say, Norway and Russia or Norway and the United States are not that big — certainly not as big as one might expect given how differently each country arranges society and the care within it. Like every paper, it concludes with a whole bunch of additional interesting studies that could help clarify, but the big implied assertion is: well, people keep performing gender the way they perform gender; the state can help, but also we need to talk a lot more to individuals about why they feel and act the way they do.

A few months ago, I asked readers to tell me about their leisure in a Google Survey. And it was interesting — 1024 of you responded, and I’ve read or scanned all of these responses — and the most striking thing was how divided the responses were: either people responded because they have a great relationship with leisure, and wanted to tell me about that (and also how equitable access to leisure felt within their relationship!), or people wanted to talk about their deeply shitty relationship with leisure, and how they felt they had no time for actual leisure in their lives even though they were constantly doing things that maybe, maybe, could be considered leisure (Is watching Netflix because you can’t think of anything else you have energy to do leisure? Is scrolling Instagram? What about watching your kids’ soccer game?)

Leisure becomes remarkable in abundance or absence. But those feelings of abundance and absence are, often, conversations about quality, because very few people have no time, none at all, in which they are not explicitly working for pay or caregiving. But low-quality leisure can feel like no leisure at all. And if you ignore what renders leisure low or high quality — in conversations as partners, as families, or as friends — it becomes all the easier to exacerbate the leisure gender divide.

So what if — in the way that families allocated and conceived of time, or even in the way that surveys like American Time Use counted leisure — what if we came up with a different arithmetic? What if an hour of leisure that’s mixed with casual caregiving responsibilities only counted for 30 minutes? What if a vacation wholly planned and facilitated and maintained by one person only counted as, say, 1/4 of “leisure”? What hobbies that take place more than five miles from home without time constraints count as double, because they feel as double? How would that change our understanding of who gets and deserves leisure — and if it doesn’t, what’s the story we tell ourselves about why women just generally deserve less of it?

I always want to hear your thoughts — but I especially want to hear your thoughts on this idea. Is your leisure, right now, in this moment, high or low quality? What makes you advocate for more, or accept things as they are? Does the understanding of “high” or “low” quality enter into the conversations you have with your partner? Tell me more, tell me everything. And yes, this is a conversation that’s open to paid subscribers, but if you want to join that conversation (and get a whole lot more, too) you know how.

I would love you to also spend some time investigating the gendered role that golf plays in work ie corporate golf tournaments. As an elder millennial entering management in an industry where my bosses were so excited when covid restrictions lifted enough that golf tournaments were back, I want to burn golf as business development to the ground. It’s male and white and we are still telling young female engineers that they need to learn to golf instead of telling old men engineers that we shouldn’t be doing business on a golf course anymore. Anyway I hate golf.

Show me a group of four women of working age who all can schedule 6 hours of uninterrupted leisure time on a weekend. Half the issue is that in order to have the full “golf outing experience” is you have to find peers who are *also* available for that amount of time. Even if individual women desire to eschew societal norms and invest in their own leisure time, best of luck finding a critical mass of other women to participate with you.