Whose Bodies Get Studied

And why it matters so much. Plus: how to spot an inclusive study

What happens when the vast majority of knowledge about how our bodies work….comes from studies of a certain type of body that may or may not work like our own? Bad advice, bad knowledge, bad medicine, bad health, bad self-understanding. In her new book, Up to Speed, Christine Yu investigates the consequences of focusing so much bio-medical research on cis-gender men — and how it’s affected everything from sports bra design to the rules about who can participate in the ski jump at the Olympics.

Why are female athletes so susceptible to disordered eating? Why don’t scientists just study more women and trans people? How can you tell if a study is still just studying cis-dudes or if it’s trying to be inclusive? This interview has it all — and like so many Culture Study interviews, my hope is that you might not think you’re interested in this topic, but if you get started, you’ll find yourself much more engaged than you thought.

You can find more about Christine Yu here and buy Up to Speed here.

You write that “when women don’t conform to the accepted mold, it’s no surprise that their so-called shortcomings are blamed on their bodies, especially features that distinguish women from men— chromosomes, hormones, genitalia, gonads, and secondary sex traits. These characteristics are then labeled as deficits and defects because they don’t match the male model.”

I want to start by unpacking this normalization of women’s bodies as“anomalies.” How does this idea manifest in the athletic world but also the world-at-large?

Sports has always been a masculine domain. For the Ancient Greeks, the Olympic Games was a domain for men to test their strength, display their masculinity, and celebrate the male form. In the late nineteenth century, sports were seen as a way to teach boys and men the virtues they needed to succeed—courage, grit, self-control—at a time when urbanization and industrialization spurred concerns that men would become weak and effeminate. (We weren’t at war! Work required less physical labor! Boys were being taught by women in schools!) Teddy Roosevelt praised sports like football because men tested their mettle in the regimented, battle-like formations.

On the other hand, a woman’s capacity to bear children was central to her role in the home and in society so anything that could potentially harm a woman’s reproductive capacity was considered off limits. The Ancient Greeks and Romans thought physical activity would damage a woman’s reproductive system. In the 19th century, the medical community believed that menstruation depleted women of “vital energy” and any activity during this weakened state would leave her incapable of bearing children. That’s why when women wanted to participate in exercise and sport, they were viewed with skepticism because those activities were seen as unfeminine and incompatible with women’s frail bodies.

These ideas and beliefs have given rise to so many myths like pregnant women shouldn’t exercise. Or, my favorite, that the uterus and ovaries will fall out or burst if we run too far or exert ourselves too much. While these beliefs might seem silly, they are persistent. Women weren’t allowed to participate in the ski jump in the Winter Olympics until 2014—10 years ago!—because the then-head of the International Ski and Snowboard Federation thought that the women’s uterus would burst upon impact. The upcoming Paris Olympics will be the first Olympic Games to achieve full gender parity with an equal number of athletes and events (so opportunities to medal). It’s the XXXIII Olympiad.

The result is a paradigm where men are the norm in the sport and women are the outliers. The whole structure, cultures, and experience of sport was developed around the experience of boys and men. Male anatomy, physiology, and biology and men’s lived experience inform standards for athletic development and progression, guidelines for training and nutrition, and blueprints for athletic shoe, clothing, and gear design. Men, male bodies, and men’s achievements have also been the de facto measuring stick and framework to organize and understand athletic performance and progression, and women have always been assessed against these standards.

But these benchmarks weren’t constructed with girls and women in mind and ignore the specific experience of what it’s like to be a girl or woman in sport. They aren’t designed to promote the health and performance of women athletes, which can make it hard for girls and women to get involved and stay involved in physical activity and for athletes to have long, healthy careers. It means that women have never been given the space to test their potential and to set their own benchmarks without carrying the weight of expectations that have been tainted by what men have accomplished or misconceptions about women’s bodies.

Think about strength training. While it’s become more mainstream for girls and women to lift weights, walking into the weight room can still be intimidating and unwelcoming. Not only that, there’s still bias that influences who is and isn’t encouraged to lift weights. There was a study among high school varsity coaches that found that among those working with boys, half required their athletes to strength train while only 9% of girls’ coaches required the same. Coaches were also more likely to ask boys to strength train three or more times a week as well as year round. Girls programs, on the other hand, were more likely to include low-intensity, high-rep routines, pilates, yoga—more “feminine” disciplines and practices.

Talking about humans and their bodies within the context of sports and science is a tricky thing. Both disciplines rely heavily on binary categories that often conflate sex and gender as one and the same. Organized sports are based on sex-segregated competition categories (women’s or men’s) and scientific research classifies specimens and participants as either female or male.

Yet these either-or definitions are static and don’t accurately describe the larger spectrum of sex or gender. They unwittingly reinforce stereotypical notions of women and men, femininity and masculinity. Cisgender people are more likely to fit into these categories. For transgender, nonbinary, and intersex people, these categories don’t always adequately reflect their identities, yet they are forced to pick one or be left out. Ultimately, this idea of “being an anomaly” isn’t just limited to girls and women. It affects all people who don’t identify with the norm, especially those who are marginalized by sex and gender.

This is a big one, but you address it head on and I think it’s important for people to read it here: why haven’t we studied women’s bodies (and why, for the most part, do we continue to exclude them?)

When I asked researchers this question, they told me the same thing: women are complicated.

Scientists tend to favor simplicity, especially when the goal is to understand complex physiological, molecular, and chemical behavior. They want to eliminate as many extraneous factors as possible to reduce the “noise” in the data. That way, when they look at the data, they can more easily pinpoint—ah, this is the thing that’s influencing the outcome or that’s making the difference.

That’s why scientists tend to study homogenous strains of male rats of the same age to minimize variability. That’s why scientists recruit a standardized cohort of participants, one that’s relatively controlled and with few external variables. That’s why scientists default to men as participants.

Female bodies throw a whole wrench in the system because of menstrual cycles. The hormonal environment in female bodies is constantly changing, not just during a given month but throughout the lifespan. These fluctuating hormones influence a wide range of physiological factors aside from reproduction and fertility. They add noise to the data that scientists have to control for and that can take time and money. It’s just easier to study male bodies because they don’t experience the same hormonal fluctuations. (But their hormones do fluctuate!)

But I think that’s somewhat of a simplistic answer. It’s easy to say “scientists don’t care about women” or fault them for these biases, but it’s the systems that influence how they act and the decisions they make, which partly explains why women continue to be under-represented in biomedical research. I think we have to think about the historical perceptions about female bodies and how that planted the seeds of gender bias in biomedical research. Because when women aren’t included from the beginning, they continue to be overlooked because there’s no precedent to include them in the first place. It creates a blind spot that enables institutions to routinely exclude women and position them as an exception to the rule rather than part of the norm.

So, if you think about it, the idea that women are the weaker sex has been deeply ingrained in Western cultures since antiquity. Women were seen as the foil to men: the delicate, feebleminded, and feminine counterparts to male virility, wisdom, and masculinity. Female bodies were the inferior version of male bodies and therefore weren’t considered worthy of studying.

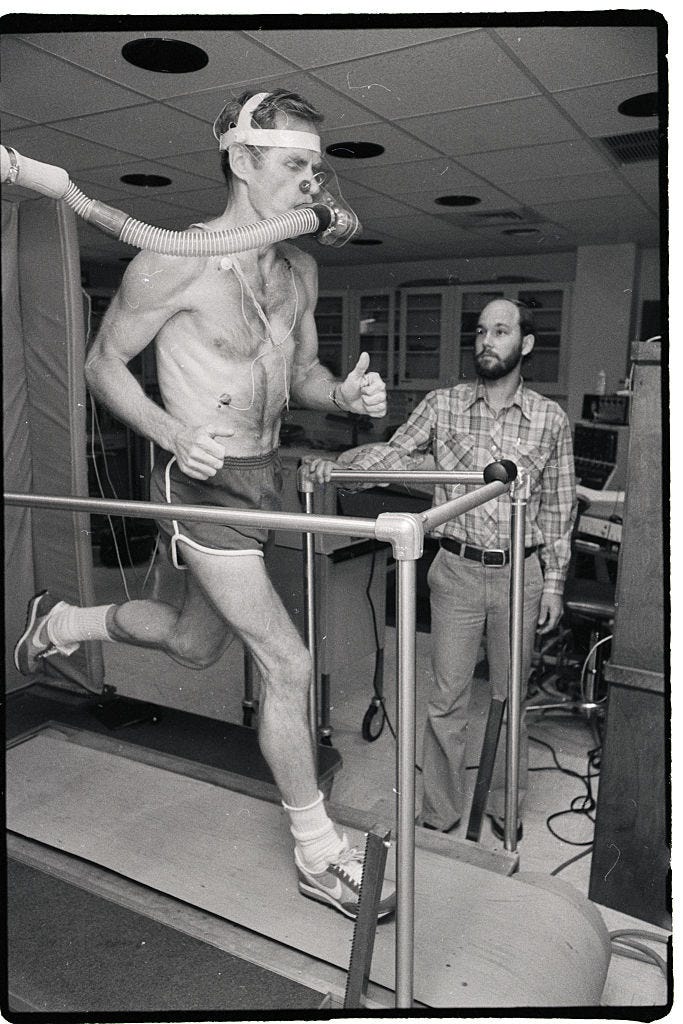

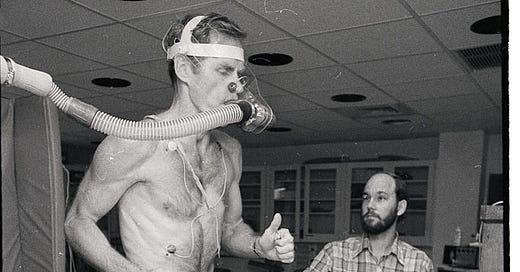

The Harvard Fatigue Lab is widely considered the birthplace of exercise science. Some of the foremost leaders in the field got their start there. When scientists wanted to study exercise, they turned to men—typically young, college-age, white men—because they were the ones who were allowed to compete and play sports and they were the ones at the universities where they were studying these things. That became the standard methodology. When the lab closed in 1947, its former students, staff, and fellows dispersed and went on to establish 17 new labs across the country, bring the legacy and methodologies of their mentors with them. They then trained the next generation of exercise scientists who went on to train the next and those methodologies were passed down. You might not think to question it because that’s what your professor taught you.

Eventually, a 70-kg man came to represent the average person in biomedical research. It wasn’t until 1993 that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act mandated the inclusion of women and minorities in NIH-funded clinical research. It’s only been since 2016 that scientists have been required to account for sex as a biological variable in preclinical research and human studies.

What that means is that funding has historically flowed more easily to studies investigating male cells, animals, and humans. Since everyone studies male specimens, journal editors and peer reviewers are more familiar with this context and may look upon those studies more favorably for publication. Meanwhile, researchers have to clear countless hurdles to prove a study involving female specimens or participants is worthwhile. They may be met with skepticism because the methodology and research questions are novel. Or maybe the study question has already been investigated in men so the study is deemed redundant and not worthy of funding or publication.

All these factors create a huge gap in the research. Between 2014 and 2020, only 6% of sports science research focused exclusively on women and women made up only 34% of research participants.

You address this in so many ways in the book, but I think it’ll be useful for readers to understand: what are the most vivid and dangerous implications of excluding women from sports research? Can you connect the dots, for example, between the prevalence of eating disorders and amenorrhea and research exclusion? I’m thinking too about how it’s just so much harder to know how to train in a sustainable way.

The lack of high quality research on women means there’s a void of evidence-based sports guidelines tailored to women, elite or recreational athletes. The repercussions play out in the higher rates and worse outcomes for injuries like anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears and concussions in women’s bodies to uncomfortable gear and sports bras that don’t fit the proportions of women’s bodies. It makes it harder to get involved and stay involved in exercise and sport. It may mean unnecessary injury and long-term health repercussions. It may mean girls and women sell themselves short because their fitness and athletic progression doesn’t look like it “should”.

Think about baseball and softball. Players across both sports suffer from similar rates of shoulder and elbow injury. Yet, there are five-times as many peer-reviewed research articles on baseball compared to softball. That’s a much more substantial evidence base, which means there are guidelines around pitch counts in youth baseball, research on developing pitchers, and protocols for return from injury but there isn’t the same level of guidance for softball.

One of the most vivid examples of the implications of excluding women from sports research is the story of pro cyclist Alison Tetrick, which I share in the book. She moved pretty quickly up the ranks but she assumed that being uncomfortable in her saddle came with the sport. Her discomfort not only kept her from riding in an optimal position at times, it led to tremendous swelling and tissue damage in her genital area. It got so bad that she eventually had to have plastic surgery to trim the excess skin so that she could continue riding. Afterward, she learned that many pro riders have had the same procedure multiple times. They just never talked about it.

The problem stemmed from the saddle. The women’s saddle was based on a design developed for men. There’s a cutout in the center to relieve pressure and increase blood flow to prevent numbness and erectile dysfunction in men. When it came to adapting it for women, designers made the saddle wider and the cutout bigger to accommodate women’s generally wider hips. The problem is that while the cutout worked for men, it essentially created a vise around women’s labia where the tissue would descend into the cutout and swell, leading to pain and tissue damage. I feel like some basic user testing at the beginning of the design process could have prevented some of these issues!

Another example is sports bras. The sports bra wasn’t invented until 1977. When researchers wanted to study breast biomechanics in the 1980s, they were laughed at. Men (who dominated the field) didn’t understand what breasts had to do with exercise and performance. It turns out a lot! One in four people with breasts said that breasts were a barrier to physical activity and is higher among people with larger breasts. The ratio increases to one in two among adolescent girls, which could partially explain the high drop-out rate from sport among this group. So many women I spoke with talked about how they felt like they were robbed of their ability to be physically active because they couldn’t find a good, supportive sports bra.

It turns out the breast tissue moves in really complicated patterns. That movement, and any associated pain, can influence how you move the rest of your body such as your running mechanics. If you don’t study this movement, you can’t design a garment that can support the tissue during exercise. Researchers really didn’t start studying breast biomechanics in earnest until the 2000s, which might explain why sports bras haven’t been great for a long time.

Interestingly, two areas that researchers were paying attention to were the menstrual cycle (especially the absence of a cycle or amenorrhea) and eating disorders. As more and more girls and women began to play sports after Title IX, doctors noticed that they experienced altered or delayed menstrual cycles and were exhibiting disordered eating patterns. I think there was a reluctance to call attention to these factors that were considered decidedly “female” because it harkened back to those old fears that exercise was bad for the reproductive system. If they drew too much attention to these issues, women could lose their hard-won access to the athletic arena.

But I’ve always wondered why eating disorders aren’t taken more seriously, especially since they have among the highest mortality rates among mental health conditions. I think it has something to do with the fact that eating disorders are seen as predominantly an issue that affects women (which isn’t true). It’s also seemingly about appearance, about wanting to look a certain way, about vanity. Again, what does that have to do with performance?

That bias dismisses the fraught relationship between food, sports, body image, and diet culture as uniquely feminine. It diminishes the strong pressure many girls and women face to conform to a certain body type, which can lead to restrictive eating behaviors and under-fueling, which in turn can lead to menstrual cycle disturbances, which in turn can lead to bone health issues and a wide range of other physiological issues that we’re only just starting to understand more fully.

But because girls and women may look fit and look the part of the athlete, they’re praised by coaches and others. If girls and women are winning in the short-term in these slim, lean bodies that don’t menstruate, what’s the problem? It reinforces habits that may not be sustainable or healthy in the long-term.

The feminist theorist in me keeps thinking about how the treatment of women’s bodies as anomalies is part of the larger understanding of women’s bodies (and their bodily functions) as abject — gross and unspeakable. I appreciated how you explored the ways in which people internalizing that idea, particularly when it comes to menstruation, has led to so much unnecessary confusion when it comes to training. Can you talk a little more about the period chapter — and maybe a bit, too, on how you’ve seen scientists, doctors, and athletes figure out how to avoid the abjection stigma?

Menstruation is so central to this story because it was the basis by which men often excluded women from sport and from scientific studies. And yet, it’s also connected to this thing—fertility and reproduction—that is traditionally held in such high esteem with regard to women’s role in society. It’s such a contradiction—your ability to menstruate means you can (theoretically) bear children but the actual act of menstruation is considered gross. Yuck. Who wants to talk about that? Plus, since menstruation is tied to fertility, which is adjacent to sex, we don’t want to talk about it for that reason either. The abject nature of women’s bodies also means that doctors and scientists didn’t necessarily want to study it because the female body was seen as defective. If researchers did study women, it was usually in relation to a “female issue” like reproduction or breast cancer.

It’s created a situation where we only learn about menstrual health, if at all, in relation to our reproductive system. We don’t recognize its connection to female physiology and health as a whole or that the cycle can be considered a fifth vital sign, like your pulse or breathing rate, giving you insight into what’s going on inside your body. It’s left girls and women with a gaping hole in understanding their own bodies, not only how the body functions but what it means to exist in a body that menstruates, including what’s normal and what’s not. I can’t tell you the countless times women have said to me—in interviews, in response to the book: I didn’t know this about my own body. Why didn’t anyone tell me? Why don’t we learn about this?

A sports scientist I spoke with who has worked with Olympians and other elite athletes said that this tight-lipped culture means that people are afraid to mention that they are suffering from cycle-related symptoms because they’re afraid to be seen as weak or it might affect their playing time. That fear trickles down to recreational athletes and regular people too. Girls and women are more likely to drop out of sport for preventable reasons like fear that their period will get in the way or fear of leaking. Or they try to control or eliminate their cycle completely.

It’s an interesting dichotomy because athletes and other fitness-minded folks LOVE talking about their training, nutrition, recovery and sleep habits. Nothing is off limits, except menstrual cycles—especially between athletes and coaches, who are primarily men. Even though more than 80% of people who menstruate experience at least one cycle-related symptom. Even though the more symptoms people experience, the more likely they are to change their exercise routine or skip a workout or sporting event. We’re left to shrug and accept that we have to put up with these crappy days throughout the month and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Scientists, doctors, and athletes have started to reclaim the menstrual cycle, especially in the last few years. More athletes, especially at the professional and elite level, are talking openly and plainly about their cycles, including Mikaela Shiffrin last year when she was on the verge of becoming the winningest skier in the World Cup history, man or woman.

They’re not talking about it as a good or bad thing but just part of their physiology, something they have to deal with and another factor that can affect their performance like sleep or nutrition. This normalization has also led to athletes saying, you know, we don’t want to wear white shorts when we compete because that’s an unnecessary layer of anxiety when we have our period. It even led Wimbledon to change its strict all-white dress code to allow players in the women’s game to wear black undershorts.

However, I do want to note that we need to be careful not to swing to the other extreme and make everything about periods. Because of the increased interest in the menstrual cycles influence on fitness and performance, naturally there are questions about whether fueling needs and training adaptations should vary depending on whether it’s the high- or low-hormone phase of the cycle and whether doing so could improve performance and prevent injury. If you look around social media, everything is about cycle syncing and hormones but the scientific evidence is currently a mixed bag and there is no consensus. I think it’s important to remember that we are not only our hormones but the hormones are one piece of the larger picture.

Some of our readers are pros at this, but for others: How did you learn to do close reads of the “methodology” portion of scientific papers? What did you learn to watch out for or look for (particularly when it comes to studies that are trying to be more expansive and inclusive with research subjects?)

I was pre-med in college so I’m familiar with biology, chemistry, anatomy, and physiology as well as the basics (like basic basics) of lab experiments and how those experiments translate into the different sections of scientific papers. I also took statistics in graduate school but, to be honest, I don’t remember much! I still Google “what does odds ratio mean?” and other terms. I definitely don’t want to overstate my academic background but I do think that it gave me a starting place for understanding scientific concepts and making sense of these papers. I also attended a session on how to read scientific papers at a conference for health care journalists. It reinforced a lot of the hunches I had about how to approach interpreting studies—how to assess the credibility, applicability, and clinical relevance of the research.

However, I will admit that I haven’t always been good at reading scientific papers. I used to skip over the methodology section to get to the good stuff—the results and discussion. As a non-scientist, I didn’t necessarily care about how a study was set up because I wasn’t going to replicate it. I generally assumed that the researchers knew what they were doing and were using up-to-date and rigorous protocols.

But methodology matters. It creates the universe in which we understand research findings, whether or not they are applicable and relevant and for what population of people. It also creates the foundation that can perpetuate a specific point of view. Without examining how studies are established and the assumptions underlying them, we can’t identify where the bias comes from. If we can’t identify the source of bias, we can’t change the system.

I do a gut check as to whether the study design and methods make sense for what the researchers are trying to study. Some of the big buckets I take note of are:

Type of study or paper: Was it a clinical study, meta-analysis, or systematic review? Was this an observational study or interventional study? Was there a control group? Were people randomly assigned?

Who or what are they studying: Human participants, animals, or cells? If cells, what kind? Were they animal or human cells? Were they male or female cells?

Sample size: How many people were involved?

Data sources: If human participants were involved, did they recruited participants? If so, how? Was it wide-spread or did they just hang up flyers in the science building? Or were they drawing data from a national database or survey like the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm)?

Demographics: What is the breakdown of variables like sex, age, race, and ethnicity?

Confounders: If people were excluded from the study, why? If people dropped out of the study, why?

Limitations of the study: Are there any red flags?

Funding: Is the study funded by government agencies, private foundations, or industry? Are there conflicts of interest that could potentially influence the interpretation of the findings?

One of the main things I’m trying to figure out is how representative of a population is the study sample. While there’s been more attention on the need to study women, just having more studies on women doesn’t solve the problem. It matters who those participants are. They may not include a diverse sample because participants, generally, tend to skew toward educated people from Western countries with few people of color. Studies based on these samples may not be generalizable to the broader population.

For exercise physiology or sports science studies, you also want to pay attention to physical activity status. Are these folks new to exercise, regular exercisers or recreational athletes, or elite athletes? That influences how applicable the findings are. For instance, right now there is a hunger for more information on active and athletic women who are in perimenopause and menopause but the majority of studies on women in this age range are done with women who are not typically physically active or new to physical activity. That doesn’t really help the person who is regularly active or performance-driven.

Lastly, menstrual cycle-related research is hot right now. One of the first questions I have is if the researchers verified menstrual cycle status and if so, how. Do they rely on self-report, blood tests, or saliva samples? How often do they verify? Does the study exclude people with irregular cycles or amenorrhea? Do they exclude people taking hormonal birth control? Or do they combine everyone together into one big study group?

If the study is intended to study the influence of reproductive hormones on exercise function or performance, you want to study people with regular menstrual cycles and who aren’t experiencing menstrual cycle dysfunction and aren’t taking hormonal birth control. That matters because the hormonal profiles are vastly different between someone with a regular cycle, someone with an irregular or absent one, and someone who is taking hormonal birth control. That affects the relevance and applicability of the findings.

Since you make your body part of the story, I don’t feel weird asking: What have you learned about your own body in the reporting of this book?

I tried really hard to keep myself out of the book! But my editor convinced me otherwise.

I’ve had to reckon with a lot of assumptions I’ve made and held about my body and my athletic identity because for so long, I’ve believed that my body wasn’t made for sports, that I wasn’t athletic.

When I was younger, I didn’t see many (any?) Asian girls playing sports. I grew up in a predominantly white community and all the athletic girls had long blond or light brown hair and lean builds. I really only saw Asian athletes once every four years during the Olympics, competing in gymnastics and figure skating. While athletic bodies are generally antithetical to the Asian idea of beauty that I grew up with, athletes like Kristy Yamaguchi and Amy Chow still fit the mold—thin and petite—but I still couldn’t relate to them because my body didn’t look like that.

The other reason I didn’t think my body was made for sport was because as I got older and started exercising and playing sports more, I was often injured despite doing everything that I thought I was “supposed” to do. Following a training plan and not bumping up my running mileage too quickly. Strength training. Dynamic warm-ups. Nutrition. Recovery. You name it. And yet, I’ve torn the ACL in my knee three times (twice on the right, once on the left) and my meniscus twice. I dislocated my shoulder while swimming. (I know. I know! Who does that?) I’ve worn down my rotator cuff in my shoulder from overuse. That’s not even counting the bouts of plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, IT band syndrome, and achy hips. I blamed my body and often felt like my body was trying to tell me something.

But over the course of reporting and writing this book, I realized that it wasn’t my body that was telling the story. I was imposing a story on my body. It’s made me think about how the narrative I’ve been told by others—and have told myself—about my body and its place in sports has influenced how I move through the world of fitness and athletics.

For example, on more than one occasion, my doctor has told me that I have “loose joints” as an explanation for my injuries. Even if that is the main contributing factor, what can I do about something that’s just part of my physiology? It’s the same way I feel whenever someone tells me that women are more prone to ACL tears because of our wider hips and hormones. Great, but what can I do about that?

Our bodies don’t live in a vacuum as bones, muscles, ligament, etc. We’re influenced by our environment, the opportunities we have or don’t have to move our bodies, access to training and coaching, encouragement. It’s also recognizing the larger system in which we’re operating culturally and socially and how that influences my lived experience with sport and movement.

Having that perspective has allowed me to give myself more grace. Instead of beating myself up because my body doesn’t seem to respond to exercise the same way as it did when I was younger, I can now step back and say, “OK, your body in your forties is physiologically different from your body in your twenties. Of course I can’t expect to train the same way and see similar results.” Or, when I tore my ACL for the third time skiing last winter, I wasn’t mad. I mean, I was mad that I missed a powder day but I wasn’t mad at myself or my body. It was a huge difference compared to my reaction to the other times I injured my knee. It’s lifted a huge burden that I’ve carried for many years. ●

You can find more about Christine Yu here, buy Up to Speed here, and sign-up here for her newsletter, Reading Between the Lines.

The first thought I had when reading this was, “We need to be teaching this book in journalism schools and education schools.” Along with many other books about the body (“Trans Like Me” comes to mind) that help us see how the stories we are telling about the body shape our culture and curriculum, which then re-shapes our bodies. I went to an excellent J school and then an excellent MEd program, but my training in reading studies in both was cursory—I too flip to the “conclusions” without necessarily being able to analyze the methods. This then influences how I write a story or design curricula, which then shapes how other people see their bodies. I’m so glad this training is available through further professional development but it really should be 101-level content for anyone who needs to do critical thinking not only on their own behalf but for readers and/or students if their own.

Caroline Criado Perez's book INVISIBLE WOMEN addresses this as well, for example: Women are 70% more likely to sustain life threatening injuries in motor vehicle crashes because automobile manufacturers only use dummies with male weight distribution patterns. And on and on. The world has been designed for male safety and comfort. How did Brittney Griner end up in Russia in the first place? Because female athletes are paid so much less than their male counterparts, they pick up contracts in other countries to supplement their income.

From a health perspective, all the help I've gotten in managing menstrual problems has come from crowdsourcing advice from thousands of other sufferers online. The changes I saw were dramatic and immediate. Advice I got from physicians (women providers included) was basic and unhelpful.