Why Are (White) Men So Unambitious?

“Men don’t need ambition. They have privilege. They rise unless they work hard at sucking.”

Do you value the work that makes this happen twice a week, every week…that makes you think and introduces you to new thinkers and books and just generally thinking more about the culture that surrounds you?

Consider becoming a subscribing member. Your support makes this work possible and sustainable.

Plus, you’d get access to this week’s really great threads — I particularly loved yesterday’s on What Are You Watching, this one on all the Spring recipes you’re cooking, and this monster thread of advice.

When I was in college, every woman I knew studied abroad for at least a semester, if not the full year. I’m not being hyperbolic here: every woman I knew with any level of intimacy studied abroad. They were majoring in everything from Biology to Art History, and they studied in Sri Lanka and Ecuador and Vietnam and New Zealand and, like me, France. Studying abroad was highly encouraged at my college, and facilitated by the fact that your scholarship dollars transferred if you went to one of a half dozen or so affiliated programs; in many cases, studying abroad was significantly cheaper than paying for a full semester on campus.

And yet: I could count the number of men I knew who studied abroad on two hands. Some cited their major, but many of them were majoring in the same subjects as the women I knew who’d made it work. Others hadn’t planned their schedules and credits starting sophomore or even freshman year in a way that would make it happen. But a lot just….didn’t want to. At the time, I chalked it up to norms at the college. But earlier this week, that observation returned to me within a much larger context.

I was listening to Ezra Klein’s interview with Richard Reeves, economist and author of Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What to Do About It. The title sounds very, like, “why will no one cry tears for all the dudes,” and most of the interview is structured by Klein asking Reeves “women and people of color have been ‘struggling’ for decades and centuries, so why should we be upset the first time they outpace white men?”

I share that perspective, but like Reeves, I also think it’s worth thinking about the ways in which men (of all races, but white men in particular) have “fallen behind” on some of the key indicators of future success. For instance: when Title IX was passed in 1972, there was a thirteen-point gap between the percentage of men with higher ed degrees and the percentage of women. Today, there is a fifteen-point gap — only now, it’s in women’s favor.

Girls also have higher high school GPAs across the board, even as girls and boys score about the same on standardized testing. Reeves points to research that has shown that boys are more “sensitive” (as in, more profoundly affected) by environment — poverty, family instability, and neighborhood are more likely to have significant negative effects on boys than girls across racial categories. (Reeves uses a concept from psychology to illustrate this: Boys are more like orchids [highly sensitive to environment] and girls are more like dandelions [figure out how to survive anywhere]).

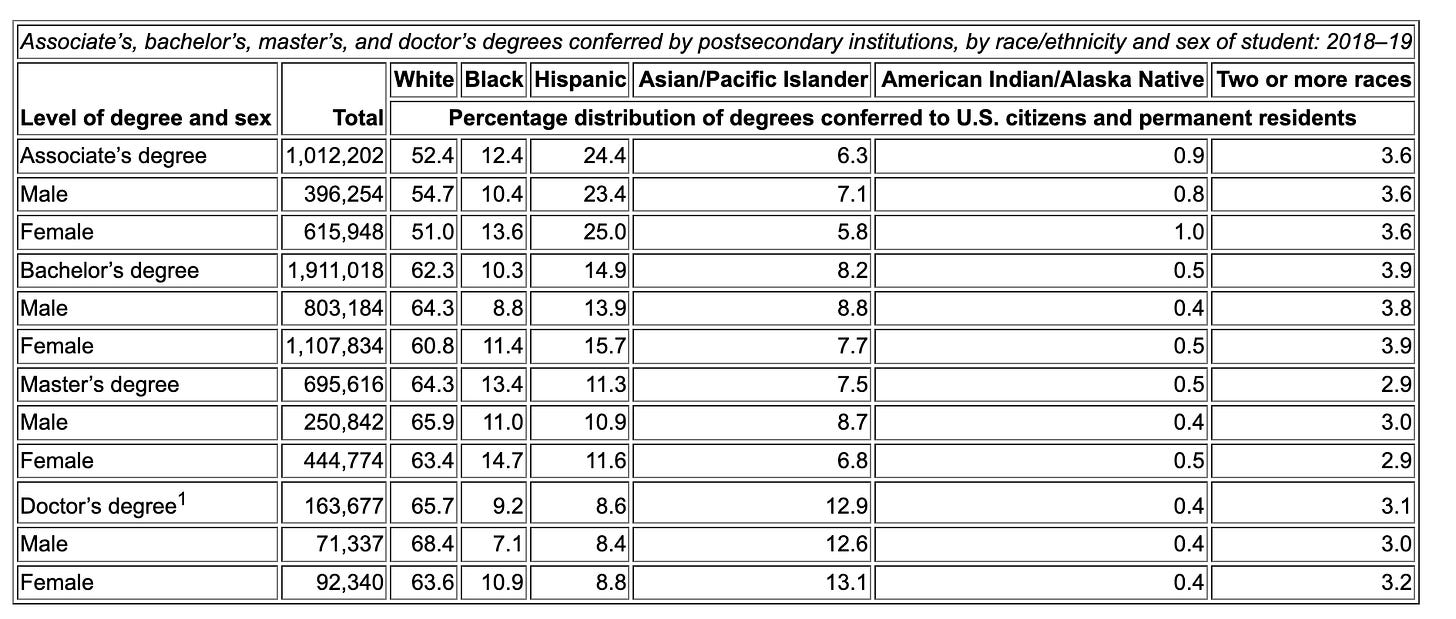

Reeves refers to the college and GPA stats as “big data points” that point to a general decline in men’s achievement. But he also highlights a whole bunch of “small data points.” Including: women are twice as likely to study abroad. (In 2016-2017, two-thirds of American students studying abroad were women) and twice as likely to serve in AmeriCorps or the Peace Corps, while men are more likely than women to live at home. Reeves doesn’t mention this, but women are also more likely to go to grad school: in 2019, there were 695,616 Master’s Degrees conferred in the United States; 63% of those went to women.

Reeves sees all of these major and minor data points making up a sort of constellation of decline:

….outside of the kind of mainstream data sets, there are these really interesting data points that I think indicate something about ambition, about aspiration, about future orientation. There’s a sense of a passivity, of drift, of a bit — checking out a little bit in among young men and boys. And you see that then playing out in things like, more likely to live at home with their parents. Women are more likely to buy their first home, et cetera. [….] So the women and the girls are actually just a little bit more metronomically going forward.

So what’s going on here? Reeves calls it passivity, or drift in ambition, and I think that’s right. But I also wonder: what if men — and more specifically, white men who aren’t first- or second-generation immigrants — have always been this passive when it comes to their future? What if they’ve never really had to cultivate “ambition,” at least not in the way we think of it now, because a modicum of success was, by some measure, their birthright? What if the “decline” of men’s ambition is just less unquestioned access to power and privilege?

Reeves argues that part of the reason boys and men struggle in school — from elementary school up to college — is because school is arranged in a way that privileges traits and skills that are more pronounced in women. Organization, planning, that sort of thing. Setting aside the fact this sort of gendered understanding of labor and skillset reinforces and excuses patriarchal structures, particularly in the home, you can see how that understanding also explains why fewer men study abroad, or serve in the PeaceCorps, or move out of their parents’ homes. All of those things require significant planning and organization — down to the fact that many (not all, but many) study abroad programs have language requirements, and to be at a certain level of fluency by your junior year of college often means laying the groundwork in high school.

So let’s follow the argument that achieving these markers of ambition and success (college application, college completion, study abroad, home ownership, graduate school) requires more planning and organizational skills, and women have more planning and organizational skills, so now that Title IX has lifted the more explicit barriers to entry, they are zooming past their male peers. That makes some sort of sense. But why do women have these skills? Why have they honed and refined them the way a culinary student hones and refines their skills with a knife?

Because they have to. And they have to hone them even sharper if they’re a woman of color, if they’re undocumented immigrants, or if they start school without English fluency. Organization and planning become the box you step on in order to start at the same position of societal privilege as the white men in your class. When it becomes visible, or “too much,” it’d coded as “ambitious”; in truth, it’s just doing all you possibly can to create the conditions and infrastructure conducive to success.

Women begin to internalize the necessity of this infrastructure at a young age. They see it in the media they consume, which is filled with Organizational Queens: Elle Woods, Olivia Pope, Jennifer Lopez in The Wedding Planner, Leslie Knope, Janine on Abbott Elementary, Harriet the Spy, Lara Jean Covey, Hermione Granger, Amy Santiago in Brooklyn 99, the list goes on. Who is Zelda if not an Organizational Queen???? Who is Taylor Swift? Who is Beyoncé??? Sure, many of these characters/actual celebrities end up on some romantic sidequest that “softens” their ambition in some way, but the real message is that successful women have intricate plans and the tenacity to follow through on them.

Women also learn by observing the older women in their lives: mothers, of course, but also every other woman whose lives we know enough about to understand where they started and where they arrived. Girls understand very early how pregnancies and religious maxims and romance and peer pressure can derail loosely-set dreams and goals. They know the look and feel of bitterness and regret. They know that jobs and promotions and careers don’t go to the “best” candidate.

So if there’s so such thing as fairness, they have to tip the scales back in their direction somehow. Planning, absolutely, but also grades, and finely-tuned and balanced resumes, and legible, unarguable measures of competency: GPA, honors, credentials, degrees. (Sidenote: There’s a whole additional conversation to have here about women who struggle with planning and organization, and how that messes with both their understanding of ambition and femininity, and I hope we have it in the comments.)

Women also know that even that will not be enough: that a PhD doesn’t prevent a date from lecturing on your area of expertise, that the gender pay gap (women make 82 cents to every dollar a man makes) hasn’t budged in two decades, that women make up just 44% of tenure-track faculty and 36% of full professors, that just one in five equity partners in law firms are women, that feminized trades have far less earning potential than masculinized ones, that even if single women are two percent more likely to buy a home than single men, they also sell those homes for two percent less. They know that women hold about two-thirds of all student debt. Even if they don’t know those specific stats, they know.

For women of color, the reality only intensifies. Hispanic women earn 57 cents, Black women earned 64 cents, and Asian-American and Pacific Islander women took home 75 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men. Again, you don’t have to know the specific stats to know, and to act and plan and organize accordingly. You can’t hustle your way out of structural inequity, but that doesn’t mean that women don’t try really, really hard to do so.

So if that’s the lesson girls are internalizing….what about boys, particularly but not exclusively white boys? That success is yours to lose. That plans are unnecessary. That things will work out, because they always have and always will. I don’t think anyone has to teach boys this — it’s just the way our society (and, for that matter, any white patriarchal society) works. “Men don’t need ambition,” one reader told me, when we were discussing the ambition gender divide over on Instagram. “They have privilege. They rise unless they work hard at sucking.”

Only recently — as their power has (very gradually) eroded, and they’ve come to face more legitimate consequences for sucking — has this lack of white male ambition been presented as a problem. And the reaction to that “problem” has been outsized. Hillbilly Elegy, the white-focused narrative around Deaths of Despair, the backlash to critical race theory, the other backlash to #MeToo, the other backlash to Black Lives Matter, the coordinated attempts to legislate trans lives out of existence, the ongoing rollback of reproductive rights, “Make America Great Again” — all of it, all of it, is an attempt to restore or defend unquestioned white cis-male privilege.

Reeves and Klein both argue that you can recognize the damage and suffering of those who suffer the most within our current system while also feeling compassion for the men and boys who also struggle within it. Trying to make life less difficult for all people means also trying to make it better for men, and compassion is not a finite resource. And I get that, in a sort of universal design sort of way: figure out a system that removes barriers for those with the least amount of access and you end up designing a system where everyone benefits.

But I don’t see us attempting to create or even imagine new systems: not in education, not in the workplace, not in the family or the community. Instead, we have a whole bunch of people who feel like they’re being “left behind,” when they were born on the 20th floor and the elevator to the 25th floor isn’t working quite as reliably as it once did, so they’re deeply aggrieved and panicky and blaming the entire situation on the people who’ve recently moved into the 6th and 7th floor. Then you have a whole bunch of people who’ve spent their entire lives trying to plan and procure the materials to jerry-rig a ladder from the ground or the 4th floor or the 4th floor to the 10th. They know that unless they maintain utmost vigilance — watching that ladder every hour of every day — it risks falling apart entirely.

At some point people just say: fuck it, there has to be more to life than watching and building and re-building this cursed broken ladder.

There is — and there’s absolutely a conversation to be had (and one I’ve had with Rainesford Stauffer) about what it looks like to de-couple “ambition” from “career.” But if you’re curious about why so many women in their late 30s and 40s are exhausted or dropping out of the workforce entirely, why so many are trying to figure out where their ambition went — well, when the race has no end point, sometimes your endurance just runs out. That’s the fault at the heart of #GirlBoss feminism and white feminism more broadly: if the goal is simply matching the success of white men without re-imagining the world that privileged it in the first place, the whole enterprise is a dead end.

There’s an old joke from grad school that pops up in the trenches of a bunch of other professions. “Just think,” someone would say over beers, “how much work you’d get done if you had a wife.” It’s a call back to an old way of academic life, when men in offices filled with dusty books were permitted to live the life of the mind. But it’s also harkening back to a time when white men’s dominance of the academic sphere went unquestioned.

Today, I think of the proposition at the heart of that joke differently. Just think how much you’d get done if you weren’t also handling the mental and domestic load of your home, sure. But also: Just think of how much work you’d be able to get done if you weren’t constantly fighting overt and covert prejudice related to your gender or race or sexuality or body size or accent. Just think how much work you could get done — for your job, but also for the things that matter to you outside your job — if you were thinking about the things you wanted to think about, instead of trying to anticipate and accommodate and counter a game where you’re always at a disadvantage.

Just think of who’d you’d would be if you didn’t have to think about your identity at all — if it went unquestioned and unremarkable, if it just was. Just think. ●

If you enjoyed that, if it made you think, consider subscribing:

Subscribing gives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. It’s also how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Links Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. Plus it’s a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week!

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

This week’s WORK APPROPRIATE is ALL ABOUT MEETINGS. Meeting culture, too many meetings, why are we still having meetings instead of emails and emails instead of meetings, with a co-host who has spent a lot fo time thinking about why we organize the work day the way that we do (and has implemented strategies that actually work in her own work place). Click the magic link to listen on your app of choice.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

I interviewed a Georgetown expert about the rise in women getting college degrees, outpacing young men, and he had an interesting point: For women to earn the same as men, they NEED a college degree. Basically, white men without a college degree can find jobs in construction or the trades (both of which are predominantly STILL male) and earn a middle-class salary.

Women without a college degree earn bupkis — they work in retail, restaurants, etc. He said for women to just get to the same earnings level as a man without a college degree, they need a college degree. In his view, this is what is fueling the majority enrollment of women in college today — that they understand, without a college degree, they are looking at a lifetime of low wages. Not so for men. Depressing.

I think there’s also a component of how things like ADHD and ADD are diagnosed differently depending on the person’s sex - highly organized and overachieving girls are seen as being good students, not as people overcorrecting for struggles just to meet expectations. I also suspect that’s a component of the late 30s-40s burnout women are experiencing. We’ve been overcompensating for so long just to maintain expectations instead of getting the help we need.