This is the Sunday edition of Culture Study — the newsletter from Anne Helen Petersen, which you can read about here. If you like it and want more like it in your inbox, consider subscribing.

My COVID coping strategy is stats. They are my feeble way of trying to control, or at least comprehend, the uncontrollable. If you follow me on Twitter, you know this. I cannot shut up about the numbers.

Part of my early obsession with these numbers ironically stemmed from the fact that I knew, especially in the places in Idaho and Montana where I was checking every day, that they were deeply unreliable. For months, testing was widely inaccessible, even to people who were symptomatic. Even as it became easier to access, people weren’t always getting tested after exposure or were ignoring contact tracing attempts. They needed to go to work. They didn’t think it was a big deal. They didn’t feel sick. They didn’t think it was anyone else’s business.

No matter the reason, they weren’t showing up. And so the numbers became the basement of my worry. The ceiling was so much higher, and always shifting.

Over the summer, people set new standards of acceptable behavior. We had a party, and no one got sick; we had wedding, and no one got sick, we all went out on the boat, and no one got sick. (I did not do any of these things, and maybe you did not either, but many people did). Part of the reason no one got sick was that many of these activities were outside. And part of the reason, at least in places like Montana and across the Mountain West and Upper Midwest, was that there just was not that much virus out there. The actual cases were still low enough that people could get away with COVID-risky activities.

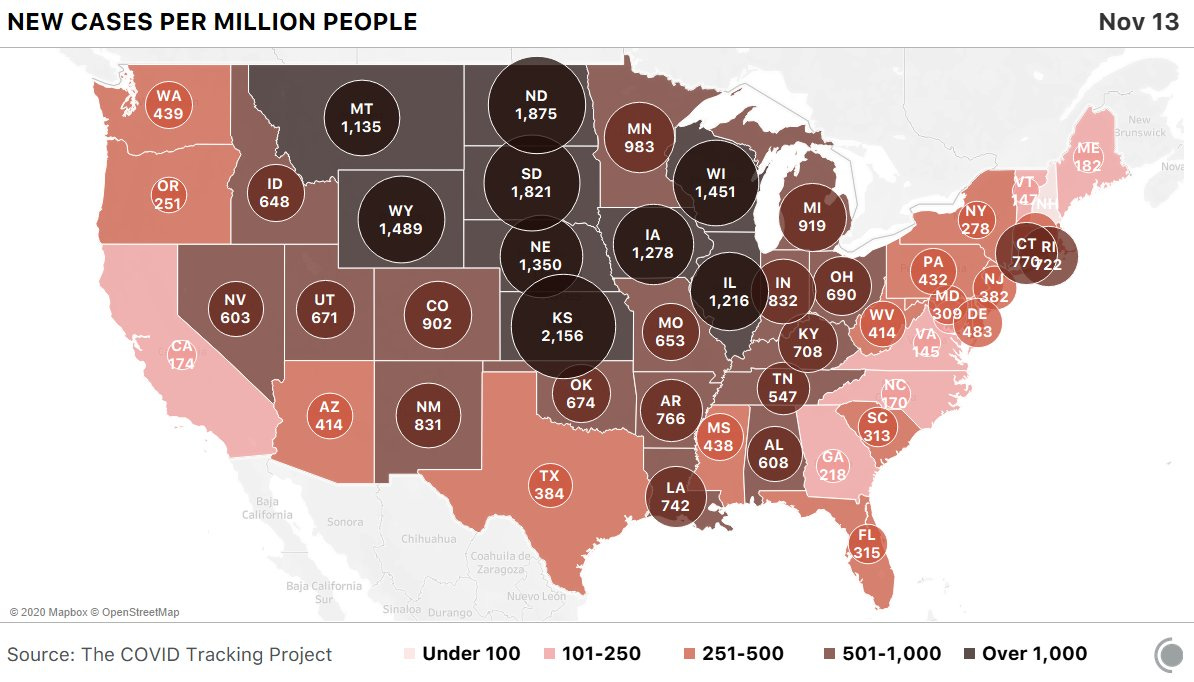

And then Sturgis happened. Half a million people came to South Dakota. Like many experts, I’m dubious of the claim that Sturgis was directly responsible for 266,000+ COVID cases. But it was a massive migration of human bodies, to and from the state of South Dakota, and three months later, we have a map like this:

Other than college students, I don’t think people really changed their behaviors much from August until now. They kept doing the sort of things they had been doing before — and that didn’t get people sick, because there just wasn’t enough virus in these spaces. Right around Sturgis, that reality began to shift. At first, the shift was small. In Montana, for example, the case numbers held fairly steady over the course of the summer — even with a significant influx of outside tourists. (These tourists, however, were largely engaging outdoor activities within their immediate family — and, even more importantly, the governor had implemented a statewide mask ordinance for other places they did frequent, like restaurants).

But cases began their current upswing in the weeks after Labor Day weekend. Part of this was connected to college students back on campus. But part, too, was attributed to Labor Day gatherings — people gathering maskless with friends and family the same way they likely did for the Fourth of July, only this time, COVID came too.

And so the cases rose, the hospitalizations rose, and now the deaths rise. Hospitals are over or reaching capacity. There just isn’t enough staff. During previous spikes, regions could recruit staff from less afflicted areas: in April, medical personnel from all over the United States arrived in New York and the surrounding area to assist with the surge of cases. But when cases are rising everywhere, there’s no such thing as surplus staff. The resources are finite. And that’s something that many Americans, in their existence of relative abundance, have a hard time comprehending.

You likely know all of this. You have adapted your behavior over the course of the last nine months, maybe expanded your social circle over the summer, and are now coming to terms with the fact that it’s time, again, to lock yourself down as much as possible. If you or a family member is high risk, you are battling oscillating amounts of terror. You’re pissed and exhausted with what’s happening with schools. And you’re probably harboring no small amount of anger and frustration with the people, from the president to careless woman in your Instagram feed, who’ve put us in this position.

That anger, it makes sense. I read pieces, like this recent one in the AP, and want to take a bunch of sedatives and wake up when the pandemic is over. “We have an 18-year-old and a 16-year-old, and we certainly believe this is an important time of life to maybe shine a little bit,” one North Dakota man said. “We’re trying to create as much normalcy as we can. We try not to live in fear. We’ve traveled. We go out to dinner.”

But I don’t know if my anger is going to change much. The country is cleaved by belief and disbelief in established medicine, by trustworthiness or untrustworthiness of mainstream news. But I’m more convinced than every that our overarching division is between collectivism and individualism: between acting and thinking in ways that aim for the better, collective good, and in acting and thinking in ways that aim to preserve the personal status quo. I wrote a bit about this in the immediate aftermath of the election, but it’s also at the core of my thinking on the lifestyle blogger Trump vote, and my arguments about burnout and work.

The collectivist ethos translates to watchwords like “think of the best person you know, then vote in their best interest.” Individualist ethos manifests in people voting exclusively on personal tax interests. Collectivist ethos means advocating for solutions that will make life better for everyone, even if it means giving up some of your privilege. Individualist ethos means focusing first on your family’s security, and only then expanding that focus to others, but only the others you deem worthy. Collectivism means thinking about future generations and the world they will inherit; individualism means thinking about your grandchildren and what they, personally, will inherit from you. Collectivism is thinking with a sociological imagination: understanding the ways that our personal experiences are shaped by structural forces. Individualism is understanding the world, at least largely, in terms of personal psychology: what can I do, what can I resist, what do I choose.

The collectivist ethos can be perverted: in the wake of 9/11, millions of people gave up personal privacy in the name of national security. That’s a seemingly collectivist idea that resulted in race- and religion-based surveillance of millions who were also Americans. Historically, the most reliable drivers of collectivism have been war, generalized xenophobia, and racism. Still, you’d think if there was something we could frame as a nefarious, sneaky, nebulous force that demands total annihilation, it’d be this dumb virus.

That we haven’t rallied against it speaks to the tenacity of the individualist ethos in this moment. It’s been aided and abetted by Trumpism, bolstered by current levels of polarization (anti-masking as a way to distinguish oneself from and own the libs), and facilitated by the hodgepodge shitshow that is the governmental response. Financial and physical instability can lead a lot of people to narrow the cost-benefit analysis to the point that other people disappear entirely. Say your business is failing. Say your family has been trying to survive on one less paycheck for months. Would it make me feel better to see my family for Thanksgiving? Will it make my kid feel better to have a sleepover with 20 girls? Well then, that’s what matters.

It’s not that people don’t understand the risk. They just think it’s worth it — and that if they do get sick, it probably won’t be that bad. They look at what happened with the COVID cases from the White House: they all ended up okay. No matter that they had the best care possible, they were fine. Again, it doesn’t matter that we’re still figuring out the long-term health ramifications of even mildly symptomatic COVID cases. Chances, these people argue, are on their side — even if that means, just necessarily, that they won’t be on others’.

If this sounds ridiculous to you, you’re not seeing it through the individualist lens. I’m not saying you should adopt this lens or excuse it. But if you want to persuade someone who thinks this way, you have to figure out how to communicate to them in a way that’s not just someone close to them getting seriously sick and/or dying. This may require even more uncomfortable conversations — and I don’t mean to suggest that anyone should open themselves up to situations that are emotionally abusive. But if you’re a collectivist, you also have to understand how the ramifications of gatherings like Thanksgiving will not be limited to the people who make those individual decisions.

An illustrative case: Back in August, only 55 people attended a wedding reception in Millinocket, Maine. But in the month and a half that followed, that reception was responsible for the spread of the virus to 176 people. Seven of those 176 people died. And none of those seven had attended the actual reception.

Maybe that story will be effective. Maybe this tool — which shows the likelihood of encountering someone with COVID at a gathering of 10 people, county by county — will help. Maybe you can evoke the sacrifices of parents or grandparents in World War II, because some people are just really, really persuaded by anything that has to do with World War II.

Maybe you can promise a big gathering next year, or hours this year on the day-of playing Among Us or just watching a movie together. You can use the health of your own children or your cousin or your grandparents as a cudgel. Just remember that the most affective appeal to an individualist is always going to be from the people they care about in their immediate sphere. A state-wide lockdown might not change their behavior. An emailed article certainly won’t. But you might.

This advice blows. No one needs more work. We’re all emotionally fatigued and the last thing we want to do is engage in a delicate and heartfelt appeal to an obstinate friend or family member. To be clear: if you fail to convince someone, it’s not your fault. The decision is still ultimately theirs. What matters, and I mean this truly, is that you tried — and if you have any persuasion tactics that have worked with others in your life, please share them below.

I wish we had federal and state-wide leadership that didn’t reinforce the ethos of “personal responsibility.” I wish we had a massive federal relief program that didn’t make it so that “personal” Thanksgiving decisions trickle down and endanger millions of Americans who aren’t afforded the same personal choice when it comes to exposure. I really fucking wish that we didn’t have to police and plea with each other as a last ditch effort to halt further descent into national darkness this winter.

But if you feel as helpless as me, there’s little we can do besides looking at the numbers, staying as safe as possible, waiting for actual leadership, and having these grievous, exhausting, essential conversations until they start to take hold.

Things I Read and Loved this Week:

What it took to convince Portland liberals on preschool for all

A cathartic deep pan of Hillbilly Elegy

The Native voters who flipped Arizona

A true broad of the best sort

One of the most powerful essays I’ve read this year

This week’s just trust me

Reminder: Fill out the work from home survey if you haven’t already! [And please feel free to pass along to others who might be interested!]

If you know someone who’d enjoy this sort of thing in their inbox, please forward it their way. If you’re able, think about going to the paid version of the newsletter — one of the perks = weirdly fun/interesting/generative discussion threads, just for subscribers, every week, which are thus far still one of the good places on the internet. This week’s Friday thread was about what it actually means to be “middle class,” and the resulting conversation was fascinating.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

You can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.

If you're coming to tell me that Sturgis is South Dakota, not North Dakota: thank you! I knew it in my head, but clearly didn't make its way to the page. It's been amended.

This is such an important read. The explanation you provide about collectivism vs individualism is key. I study the history of Victory Gardens in WWI and WWII, and in wartime mobilization, collectivism often won out. Thanks for this piece. Will share it.